预约演示

更新于:2025-10-05

University of California San Diego

更新于:2025-10-05

概览

标签

肿瘤

其他疾病

血液及淋巴系统疾病

小分子化药

单克隆抗体

治疗性疫苗

疾病领域得分

一眼洞穿机构专注的疾病领域

暂无数据

技术平台

公司药物应用最多的技术

暂无数据

靶点

公司最常开发的靶点

暂无数据

| 排名前五的药物类型 | 数量 |

|---|---|

| 小分子化药 | 21 |

| 治疗性疫苗 | 4 |

| 单克隆抗体 | 4 |

| ADC | 3 |

| 病毒样颗粒疫苗 | 2 |

关联

46

项与 University of California San Diego 相关的药物靶点 |

作用机制 CD206抑制剂 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 美国 |

首次获批日期2013-03-13 |

靶点 |

作用机制 CTLA4抑制剂 |

非在研适应症 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 美国 |

首次获批日期2011-03-25 |

作用机制 ABL 抑制剂 [+3] |

在研适应症 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 美国 |

首次获批日期2001-05-10 |

1,352

项与 University of California San Diego 相关的临床试验NCT06505317

Artificial Intelligence for Early Detection of Peripheral Artery Disease

The goal of this clinical trial is to test an AI-based screening tool that will help to identify patients at high risk of having undiagnosed peripheral artery disease. The primary outcome measure is overall rate of new PAD diagnoses. Secondary outcomes include rate of new secondary prevention measures initiated for PAD, which will include new prescriptions for antiplatelets, PAD-dosed rivaroxaban, statins, smoking cessation counseling or referrals, and/or supervised exercise therapy referrals also aggregated at a clinic and site level.

开始日期2026-07-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06118983

Improving TRansitions ANd OutcomeS for Heart FailurE Patients in Home Health CaRe (I-TRANSFER-HF): A Type 1 Hybrid Effectiveness- Implementation Trial

This study is trying to improve the hospital-to-home transition for people with heart failure who receive home care services. The study will test an intervention called I-TRANSFER-HF, which differs from usual care by combining early home health nurse visits and outpatient medical appointments.

The study is interested in two questions:

1. Is I-TRANSFER-HF better than usual care at preventing heart failure patients from returning to the hospital within 30 days?

2. Are there parts of I-TRANSFER-HF that are easy or hard to implement in the real world?

The researchers will answer these questions by testing the intervention among pairs of hospitals and home health agencies across the country. During the study, the hospital-agency pairs will be asked to implement I-TRANSFER-HF. The researchers will then compare the results from before and after I-TRANSFER-HF was adopted. They will also interview people from these hospitals and agencies to see how I-TRANSFER-HF is being implemented under real-world conditions.

The study is interested in two questions:

1. Is I-TRANSFER-HF better than usual care at preventing heart failure patients from returning to the hospital within 30 days?

2. Are there parts of I-TRANSFER-HF that are easy or hard to implement in the real world?

The researchers will answer these questions by testing the intervention among pairs of hospitals and home health agencies across the country. During the study, the hospital-agency pairs will be asked to implement I-TRANSFER-HF. The researchers will then compare the results from before and after I-TRANSFER-HF was adopted. They will also interview people from these hospitals and agencies to see how I-TRANSFER-HF is being implemented under real-world conditions.

开始日期2026-07-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06605027

Therapeutic Ketogenic Diet to Treat Anorexia Nervosa-Specific Cognitions and Behaviors - Currently Ill Individuals in PHP Level of Care and Comparison With Standard of Care

This will be a 14-week longitudinal study with an open design. A total of 120 individuals will be recruited for an end goal of 60 individuals with anorexia nervosa (AN) who are currently in high level of care treatment at the UCSD Eating Disorder Center partial hospital program (PHP) or intensive outpatient (IOP). Forty individuals will be recruited to the TKD and 20 will be treated with treatment as usual with respect to food intake. The age range will be between 16 and 45 years. All study participants will be carefully assessed and will complete rater and self-assessments at the being at the end of the study period. While in the treatment program, the TKD group will receive catered ketogenic meals via a meal service. After discharging from program, participants will have the option to continue with the meal service or cook for themselves. After establishing ketosis, study participants will continue TKD for 12 weeks. All study participants will be followed over three, six, and twelve months after enrolling in the study, whether initiating TKD or being in the treatment as usual arm. This follow-up procedure will help determine whether symptom improvement is stable or worsens in individuals who choose to continue or discontinue the TKD intervention and in relation to the control group. After ketosis induction over two weeks, study participants will be assessed weekly for ketosis and mood, anxiety, and eating disorder symptoms over twelve weeks.

开始日期2026-01-01 |

100 项与 University of California San Diego 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 University of California San Diego 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

119,865

项与 University of California San Diego 相关的文献(医药)2026-04-01·Neural Regeneration Research

Cell therapy rejuvenates the neuro-glial-vascular unit

Article

作者: Chen, Bandy

2026-02-01·Estuaries and Coasts

Open-Coast Eelgrass (Zostera marina) Transplant Catalyzes Rapid Mirroring of Structure and Function of Extant Eelgrasses

Article

作者: Carmack, Olivia C ; Burdick, Heather ; Ford, Tom K ; Leichter, James J ; Grime, Benjamin C ; Ginsburg, David W ; Obaza, Adam K ; Sanders, Rilee D

Abstract

Seagrasses are marine angiosperms that function as ecosystem engineers, forming complex structure that enhance nearshore environments. Globally, seagrass habitats are threatened by intensifying impacts from climate change, which exacerbate non-climatic stressors such as coastal development, invasive species, and overfishing. Advances in the methodological efficacy of active seagrass restoration efforts have sought to mitigate substantial anthropogenic-induced losses. Restoration efforts along the U.S. West Coast have primarily focused on Zostera marina (common eelgrass) in shallow, sheltered estuarine environments, where most coastal development occurs. However, within the Southern California Bight, Zostera spp. also occurs along the exposed coastlines of the California Channel Islands archipelago. Despite their unique location and the ecosystem services they provide, a paucity of information persists on open-coast seagrass systems and restoration efforts. In this study, we conducted a novel transplant of Z. marina on Catalina Island and tracked temporal and spatial performance metrics (i.e., areal coverage, morphometrics, and fish assemblages) at the restoration site and seven extant Z. marina reference beds on the island from 2021 to 2024. The transplant activities successfully established over 0.18 hectares of Z. marina habitat. The transplant site paralleled or exceeded extant reference beds morphometrically (shoot density and blade length) and functionally (fish composition and fish diversity), while concomitantly providing habitat for the occupancy of, and utilization by, federally listed endangered and managed species. Our results provide a model for broadening the scope of, and augmenting strategies for, seagrass habitat recovery beyond conventional restoration spaces by underscoring the role of open-coast seagrasses in enhancing nearshore ecosystem function and resilience.

2026-01-01·CITIES

Re-thinking walkability: Synergizing the pedestrian environment and land use patterns to promote physical activity in older adults

Article

作者: Sallis, James F ; Saelens, Brian E ; Cain, Kelli L ; King, Abby C ; Conway, Terry L ; Fox, Eric H ; Adhikari, Binay ; Frank, Lawrence D

Previous studies have demonstrated that the macro-level design of cities (e.g., walkability) and the micro-level pedestrian-oriented design of streetscapes are associated with physical activity; however, the benefits of combining these features have rarely been examined. Understanding potential synergies between these two components could provide guidance for optimizing health impacts, especially for older adults. This cross-sectional investigation examined interactions among 'macro-level' neighbourhood walkability and 'micro-level' pedestrian environment, sex, and neighbourhood income in relation to self-reported frequency of active transportation and device-measured physical activity (30 minutes per day) in 352 older adults recruited from economically and built environmentally diverse neighbourhoods in Seattle/King County. Results included positive interactions between neighbourhood walkability, pedestrian environment, and sex for the active transportation outcome. The synergy was more pronounced in women, in which there were significant interactions between neighbourhood walkability and sex with scores related to streetscape design features, walking routes, and street-crossing characteristics of the pedestrian environment. Our study highlights actionable policies to create age-friendly pedestrian environments by improving route connectivity, streetscape features, and crossing safety. Prioritizing well-connected walking routes, enhancing micro-level streetscape elements, and ensuring pedestrian-friendly crossings can significantly support elderly active travel and reduce reliance on motorized transport. These results provide evidence that the pedestrian environment may enhance the health potential of neighbourhood walkability for some population segments (i.e., older women).

1,137

项与 University of California San Diego 相关的新闻(医药)2025-10-01

Dosing has successfully commenced with healthy volunteers Primary endpoints for the Phase 1 trial include safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of the combination Topline data are anticipated in the first half of 2026

SAN MATEO, Calif., Oct. 01, 2025 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Sagimet Biosciences Inc. (Sagimet, Nasdaq: SGMT), a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company developing novel therapeutics targeting dysfunctional metabolic and fibrotic pathways, today announced that the Company has dosed the first participants in a Phase 1 pharmacokinetic (PK) trial of a combination of its oral once-daily fatty acid synthase (FASN) inhibitor, denifanstat, and a thyroid hormone receptor beta (THR-β) agonist, resmetirom. Topline data from this trial are anticipated in the first half of 2026 and, if positive, are planned to be used to advance the development of the combination for patients living with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) into Phase 2, subject to consultation with regulatory authorities.

The Phase 1 PK trial of denifanstat and resmetirom is an open-label, 2-cohort study and will enroll approximately 40 healthy adult participants. The objectives are to evaluate multiple-dose and single-dose pharmacokinetics, identify any potential drug-drug interactions (DDI), and assess the safety and tolerability of the combination. Results from this Phase 1 PK trial will be used to inform the optimal dose levels of denifanstat and resmetirom to evaluate in a Phase 2 combination proof-of-concept efficacy trial in F4 MASH patients.

“The initiation of the Phase 1 PK trial is an important step in the development of a new, potentially synergistic combination treatment for MASH. As we look ahead, our goal is to combine two therapies with complementary mechanisms of action into a single tablet that will improve clinical outcomes of patients who are living with cirrhosis of the liver and who currently have no approved options,” said David Happel, Chief Executive Officer of Sagimet. “At EASL 2024, we presented preclinical data that observed the synergistic effect of a FASN inhibitor combined with resmetirom on important liver disease markers. Furthermore, denifanstat previously demonstrated significant improvements in liver fibrosis in our Phase 2b FASCINATE-2 clinical trial in a subset of MASH patients who were digitally diagnosed as having cirrhosis.”

“I anticipate that combination therapy may become the standard of care in cirrhosis due to MASH in the future, and offers the potential to improve outcomes of disease including in the most advanced F4 patients, as there are currently no approved therapies for these patients,” said Rohit Loomba, M.D., M.H.Sc., Professor of Medicine, Chief, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, and Director, MASLD Research Center, University of California San Diego, who serves as a scientific advisor for Sagimet on its ongoing development of denifanstat. “It’s exciting to see Sagimet initiate development of a combination of denifanstat and resmetirom with this Phase 1 PK trial which could answer important questions about the compatibility of these two molecules in humans. Results of this Phase 1 trial, if successful, could lead to further development of a combination of Sagimet’s fat synthesis inhibitor, denifanstat, with a fat oxidizer, resmetirom, in MASH patients, potentially including those with stage 4 fibrosis.”

Denifanstat, Sagimet's lead product candidate, is an oral, once daily selective FASN inhibitor in development for the treatment of MASH, whose strong anti-fibrotic mechanism of action coupled with its inhibition of liver fat synthesis and inflammation may be complementary to a fat oxidizer molecule such as resmetirom. Pre-clinical data presented at EASL in 2024 for two mouse models of MASH showed that the combination of a FASN inhibitor (TVB-3664, a mouse surrogate for denifanstat) and resmetirom had a synergistic effect on important markers of liver disease, including improvement of NAS (NAFLD Activity Score) by histologic analysis and more robust improvement in hepatic collagen content compared to the single agents.

About Sagimet Biosciences

Sagimet is a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company developing novel fatty acid synthase (FASN) inhibitors that are designed to target dysfunctional metabolic and fibrotic pathways in diseases resulting from the overproduction of the fatty acid, palmitate. Sagimet’s lead drug candidate, denifanstat, is an oral, once-daily pill and selective FASN inhibitor in development for the treatment of metabolic dysfunction associated steatohepatitis (MASH). FASCINATE-2, a Phase 2b clinical trial of denifanstat in MASH with liver biopsy-based primary endpoints, was successfully completed with positive results. Denifanstat has been granted Breakthrough Therapy designation by the FDA for the treatment of non-cirrhotic MASH with moderate to advanced liver fibrosis (consistent with stages F2 to F3 fibrosis), and end-of-Phase 2 interactions with the FDA have been successfully completed, supporting the advancement of denifanstat into further development. Sagimet has recently initiated a Phase 1 first-in-human clinical trial with a second oral FASN inhibitor drug candidate, TVB-3567, that is planned to be developed for acne for the U.S. For additional information about Sagimet, please visit www.sagimet.com.

About MASH

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is a progressive and severe liver disease which is estimated to impact more than 265 million people worldwide. MASH is characterized by the build-up of fat in the liver and various degrees of inflammation and fibrosis along with systemic metabolic changes including dyslipidemia (increased fat levels in blood) and insulin resistance. Patients with moderate to severe disease who have advanced fibrosis (F3) or cirrhosis (F4) have the highest risk of liver-related outcomes such as decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver transplantation. There are few approved treatments for non-cirrhotic MASH (stages F1, F2 and F3 fibrosis) and no approved treatments for MASH cirrhosis (F4).

Forward-Looking Statements

This press release contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of, and made pursuant to the safe harbor provisions of, The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. All statements contained in this press release, other than statements of historical facts or statements that relate to present facts or current conditions, including but not limited to, statements regarding: the expected timing of the presentation of data from ongoing clinical trials, Sagimet’s clinical development plans and related anticipated development milestones, Sagimet’s cash and financial resources and expected cash runway are forward-looking statements. These statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other important factors that may cause Sagimet’s actual results, performance or achievements to be materially different from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by the forward-looking statements. In some cases, these statements can be identified by terms such as “may,” “might,” “will,” “should,” “expect,” “plan,” “aim,” “seek,” “anticipate,” “could,” “intend,” “target,” “project,” “contemplate,” “believe,” “estimate,” “predict,” “forecast,” “potential” or “continue” or the negative of these terms or other similar expressions.

The forward-looking statements in this press release are only predictions. Sagimet has based these forward-looking statements largely on its current expectations and projections about future events and financial trends that Sagimet believes may affect its business, financial condition and results of operations. These forward-looking statements speak only as of the date of this press release and are subject to a number of risks, uncertainties and assumptions, some of which cannot be predicted or quantified and some of which are beyond Sagimet’s control, including, among others: the clinical development and therapeutic potential of denifanstat, TVB-3567 or any other drug candidates or combination therapies Sagimet may develop; Sagimet’s ability to advance drug candidates into and successfully complete clinical trials within anticipated timelines; Sagimet’s relationship with Ascletis, and the success of its development efforts for denifanstat; the accuracy of Sagimet’s estimates regarding its capital requirements; and Sagimet’s ability to maintain and successfully enforce adequate intellectual property protection. These and other risks and uncertainties are described more fully in the “Risk Factors” section of Sagimet’s most recent filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission and available at www.sec.gov. You should not rely on these forward-looking statements as predictions of future events. The events and circumstances reflected in these forward-looking statements may not be achieved or occur, and actual results could differ materially from those projected in the forward-looking statements. Moreover, Sagimet operates in a dynamic industry and economy. New risk factors and uncertainties may emerge from time to time, and it is not possible for management to predict all risk factors and uncertainties that Sagimet may face. Except as required by applicable law, Sagimet does not plan to publicly update or revise any forward-looking statements contained herein, whether as a result of any new information, future events, changed circumstances or otherwise.

Contact: Joyce Allaire LifeSci Advisors jallaire@lifesciadvisors.com

Source: Sagimet Biosciences Inc.

临床2期临床1期临床结果突破性疗法

2025-09-26

PASADENA, Calif., Sept. 26, 2025 /PRNewswire/ -- Alexandria Real Estate Equities, Inc. (NYSE: ARE), the first, preeminent, longest-tenured and pioneering owner, operator, and developer of collaborative Megacampus™ ecosystems in AAA life science innovation cluster locations, today announced the opening of Lilly Gateway Labs San Diego, powered by Alexandria, on the One Alexandria Square Megacampus in Torrey Pines. First launched by Eli Lilly and Company in 2019 in the San Francisco Bay Area, Lilly Gateway Labs is a shared innovation hub designed to empower biotechnology companies to develop life-changing medicines.

The latest phase of the One Alexandria Square Megacampus™. Courtesy of Alexandria Real Estate Equities, Inc. (PRNewsfoto/Alexandria Real Estate Equities, Inc.)

Lilly Gateway Labs, powered by Alexandria, at the One Alexandria Square Megacampus™. Courtesy of Alexandria Real Estate Equities, Inc. (PRNewsfoto/Alexandria Real Estate Equities, Inc.)

The new Lilly Gateway Labs in San Diego is operated in a strategic collaboration with Alexandria, uniquely integrating Alexandria's world-class real estate infrastructure, facilities and laboratory operations, and placemaking acumen with Lilly's leading scientific expertise, resources, mentorship, and access to capital through its venture network, which includes Alexandria Venture Investments. Building upon Gateway Labs' first three U.S. sites — all established within Alexandria facilities in South San Francisco and Boston — where there are over 50 novel therapeutics and platforms currently in development, Gateway Labs San Diego enhances the ability of its resident companies to bring transformative treatments to patients worldwide.

"We value our nearly two-decade strategic relationship with Lilly, and we are honored to serve as an essential partner to expand the transformative Gateway Labs platform in San Diego," said Hallie E. Kuhn, PhD, senior vice president and co-lead of life science and capital markets at Alexandria Real Estate Equities, Inc. and Alexandria Venture Investments. "Our partnership embodies our shared mission to accelerate the trajectory of disruptive early-stage biotech companies and foster critical collaboration between innovative biotechs and large pharma. The unique Gateway Labs model is an important engine for biomedical innovation that will deliver lifesaving medicines to patients in the future, and with over 90% of diseases lacking approved medicines, it remains critical that we continue to advance bold science."

Alexandria has been at the vanguard of the development, transformation, and expansion of the San Diego life science ecosystem into one of the world's most innovative clusters since acquiring its first property and pioneering life science real estate in 1994. The site of that foundational acquisition in the Torrey Pines submarket now anchors the newest phase of One Alexandria Square and is home to Lilly Gateway Labs. New highly impactful amenities enriching the vibrant Megacampus ecosystem and helping tenants attract, retain, and engage top talent include a nutritious grab-and-go café with garden seating, a destination restaurant, large event lawn, high-tech meeting venues, and a restorative walking path. The campus is also proximate to a dense concentration of renowned research institutions, such as the Salk Institute, Sanford Burnham Prebys, Scripps Research, and UC San Diego, positioning One Alexandria Square tenants at a vital nexus of opportunities for collaboration.

Lilly Gateway Labs San Diego opens with a diligently selected cohort of venture-backed biotech companies working across a diverse array of modalities and disease areas, including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, and oncology. The new site, which is located in a LEED Gold certified all-electric laboratory facility, features modular laboratory spaces with adjacent collaboration areas, scientific amenities like cutting-edge microscopy and sequencing tools, first-class operational support services, strategic programming, and dedicated building security and concierge services. To learn more about Lilly Gateway Labs, visit gatewaylabs.lilly.com.

About Alexandria Real Estate Equities, Inc.

Alexandria Real Estate Equities, Inc. (NYSE: ARE), an S&P 500® company, is a best-in-class, mission-driven life science REIT making a positive and lasting impact on the world. With our founding in 1994, Alexandria pioneered the life science real estate niche. Alexandria is the preeminent and longest-tenured owner, operator and developer of collaborative Megacampus™ ecosystems in AAA life science innovation cluster locations, including Greater Boston, the San Francisco Bay Area, San Diego, Seattle, Maryland, Research Triangle and New York City. As of June 30, 2025, Alexandria has a total market capitalization of $25.7 billion and an asset base in North America that includes 39.7 million RSF of operating properties and 4.4 million RSF of Class A/A+ properties undergoing construction and one 100% pre-leased committed near-term project expected to commence construction in the next year. Alexandria has a long-standing and proven track record of developing Class A/A+ properties clustered in highly dynamic and collaborative Megacampus environments that enhance our tenants' ability to successfully recruit and retain world-class talent and inspire productivity, efficiency, creativity and success. Alexandria also provides strategic capital to transformative life science companies through our venture capital platform. We believe our unique business model and diligent underwriting ensure a high-quality and diverse tenant base that results in higher occupancy levels, longer lease terms, higher rental income, higher returns and greater long-term asset value. For more information on Alexandria, please visit .

Forward-Looking Statements

This press release includes "forward-looking statements" within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended. Such forward-looking statements include, without limitation, statements regarding the potential impact of Lilly Gateway Labs and Alexandria's collaboration on the discovery and development of medicines, novel therapies, and treatments; Lilly's continued ability to collaborate with biotech companies and scientists; benefits available to participants of Gateway Labs; the features and amenities of the Lilly Gateway Labs site in San Diego; and the likelihood of continued commitment and efforts by Alexandria to foster innovation and collaboration. Actual results may differ materially from those contained in or implied by Alexandria's forward-looking statements as a result of a variety of factors, including, without limitation, the risks and uncertainties detailed in its filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. All forward-looking statements are made as of the date of this press release, and Alexandria assumes no obligation to update this information. For more discussion relating to risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ materially from those anticipated in Alexandria's forward-looking statements, and risks and uncertainties to Alexandria's business in general, please refer to Alexandria's filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, including its most recent annual report on Form 10-K and any subsequently filed quarterly reports on Form 10-Q. CONTACT: Sara Kabakoff, Senior Vice President – Chief Content Officer, (626) 788-5578, [email protected]

SOURCE Alexandria Real Estate Equities, Inc.

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

并购

2025-09-25

AUSTIN, Texas, Sept. 25, 2025 /PRNewswire/ -- Flat Medical, a leading innovator in medical device solutions, today announced the formation of its

Clinical Advisory Board for Chronic Pain Interventions and the appointment of

Dr. Krishnan Chakravarthy, MD, PhD, as its inaugural Chairman. This strategic initiative positions Flat Medical to accelerate innovation in chronic pain management technologies and expand its impact in the rapidly growing interventional pain market.

Dr. Chakravarthy brings exceptional expertise as an interventional pain and spine physician, and President of the

American Society of Pain and Neuroscience (ASPN). He serves as adjunct professor at the University of California San Diego and staff physician at the VA San Diego Health Care System, where he conducts pioneering clinical and translational research in interventional pain management, minimally invasive spine procedures, neuromodulation, and regenerative medicine. As a partner at the

Innovative Pain Treatment Solutions Center, he combines cutting-edge research with direct patient care. His research has resulted in numerous publications, awards, and breakthrough clinical protocols that have advanced the field of pain intervention.

Beyond his academic achievements, Dr. Chakravarthy is renowned for actively being involved in medical innovation across the pain management ecosystem. He contributes to advancing cutting-edge technologies across multiple medical device companies and has founded several successful healthcare startups. His deep understanding of both clinical needs and technological possibilities makes him uniquely positioned to guide product development strategies.

"Establishing this advisory board represents a strategic inflection point for Flat Medical," said Mark Rabe, Director of Sales at Flat Medical. "With Dr. Chakravarthy's leadership, we're not just adding clinical expertise – we're gaining a visionary who understands the intersection of technology, clinical practice, and patient outcomes. His guidance will be instrumental as we develop solutions that address the most pressing challenges in chronic pain management."

The advisory board will focus on identifying unmet clinical needs, guiding product development priorities, and ensuring Flat Medical's technologies deliver measurable improvements in patient outcomes. Dr. Chakravarthy will lead efforts to establish clinical partnerships, develop evidence-based protocols, and create pathways for rapid adoption of innovative pain management solutions.

"Flat Medical's commitment to revolutionary medical technologies such as their EpiFaithTM technology, combined with our advisory board's clinical expertise, positions us to deliver breakthrough solutions that will fundamentally transform how we approach pain interventions. The technology is a very unique offering to the space with the primary focus on patient safety" said Dr. Chakravarthy.

About Flat Medical

Flat Medical is a medical technology company focused on developing innovative solutions that enhance procedural safety and improve patient outcomes. With a dedication to advancing medical practices through cutting-edge devices and physician collaboration, Flat Medical is redefining procedural safety standards in modern healthcare.

SOURCE Flat Medical

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

高管变更

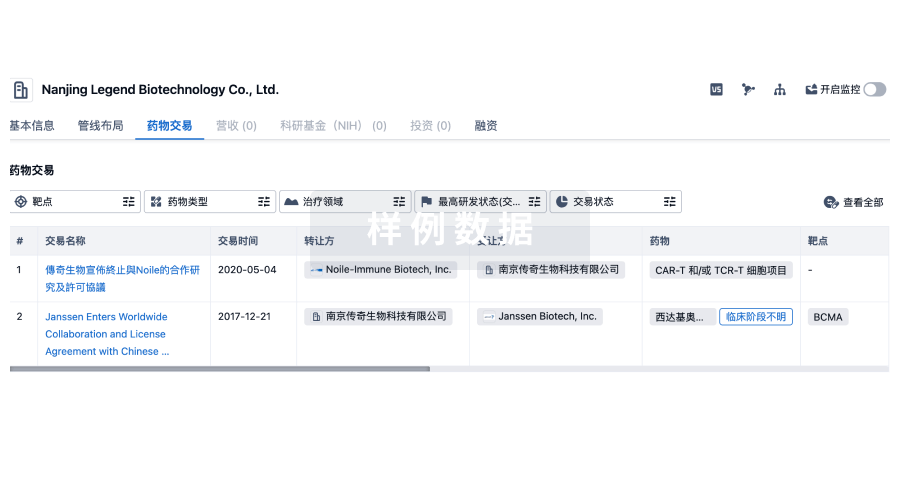

100 项与 University of California San Diego 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

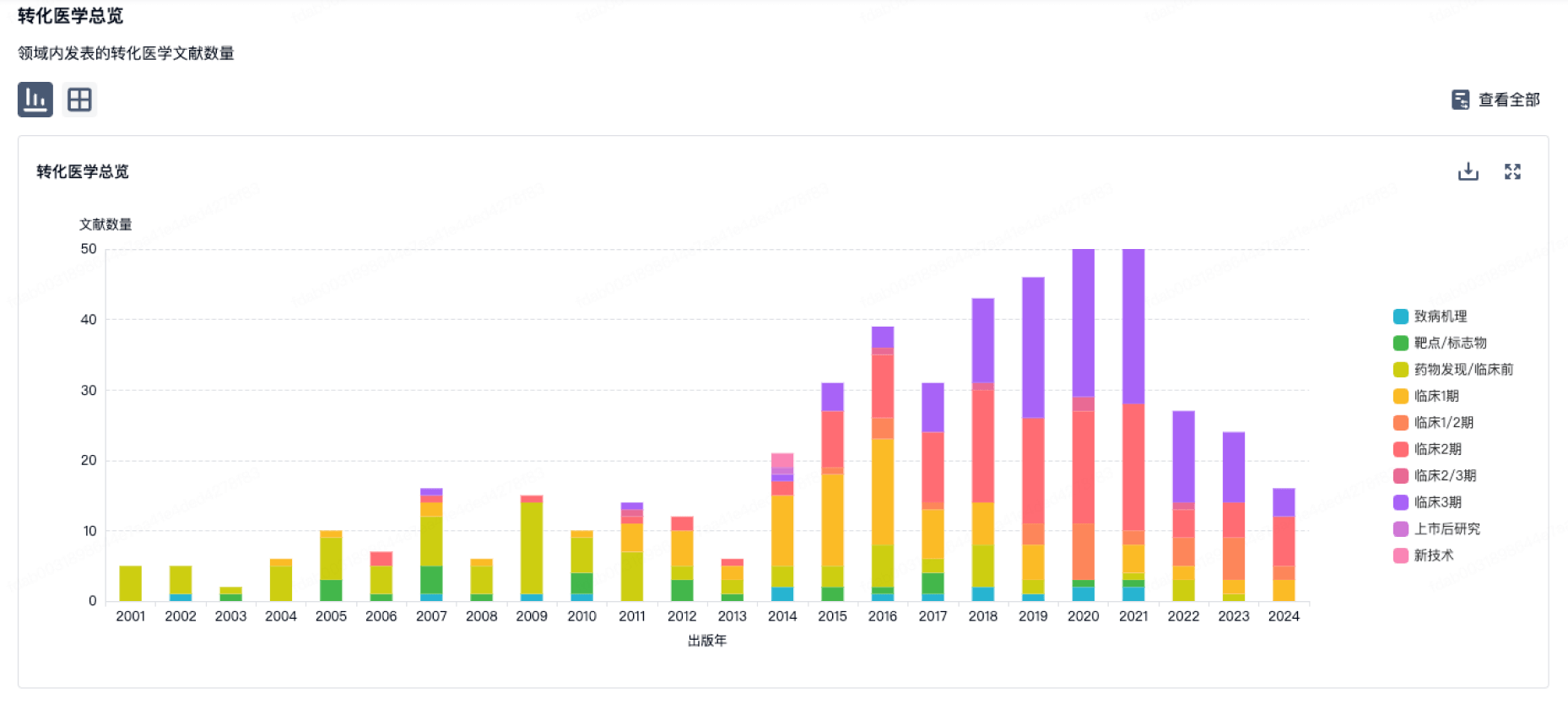

100 项与 University of California San Diego 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

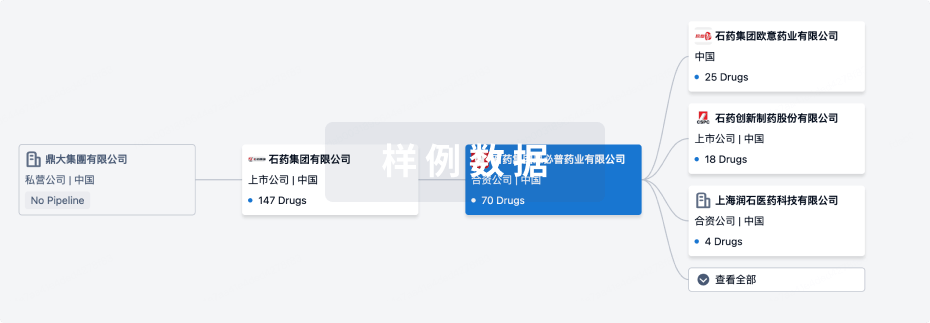

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2025年10月31日管线快照

管线布局中药物为当前组织机构及其子机构作为药物机构进行统计,早期临床1期并入临床1期,临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

药物发现

5

29

临床前

临床1期

8

4

临床2期

其他

35

登录后查看更多信息

当前项目

| 药物(靶点) | 适应症 | 全球最高研发状态 |

|---|---|---|

Eganelisib ( PAK1 x PI3Kγ ) | HPV相关鳞状细胞癌 更多 | 临床2期 |

Aftobetin ( APP ) | 阿尔茨海默症 更多 | 临床2期 |

伊匹木单抗 ( CTLA4 ) | 晚期非小细胞肺癌 更多 | 临床1/2期 |

TMX-202 ( TLR7 ) | 尖锐湿疣 更多 | 临床1期 |

AAV2-BDNF Gene Therapy(Case Western Reserve University) | 轻度认知障碍 更多 | 临床1期 |

登录后查看更多信息

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

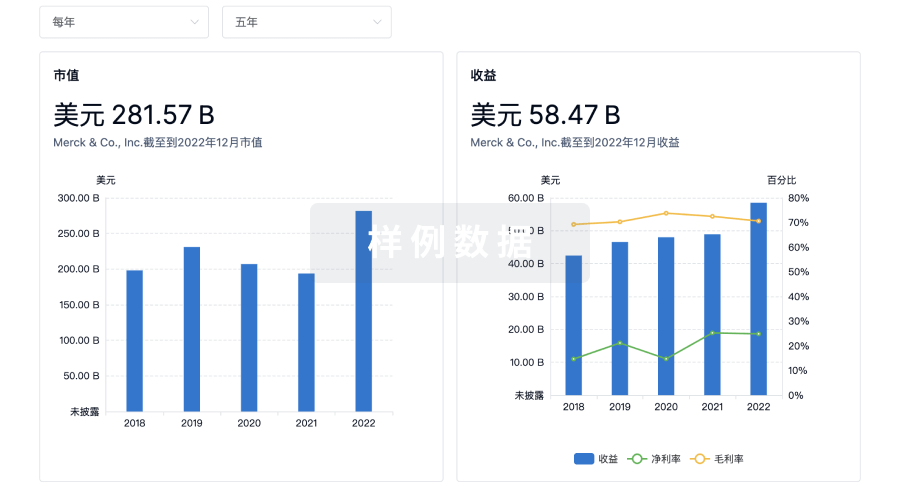

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

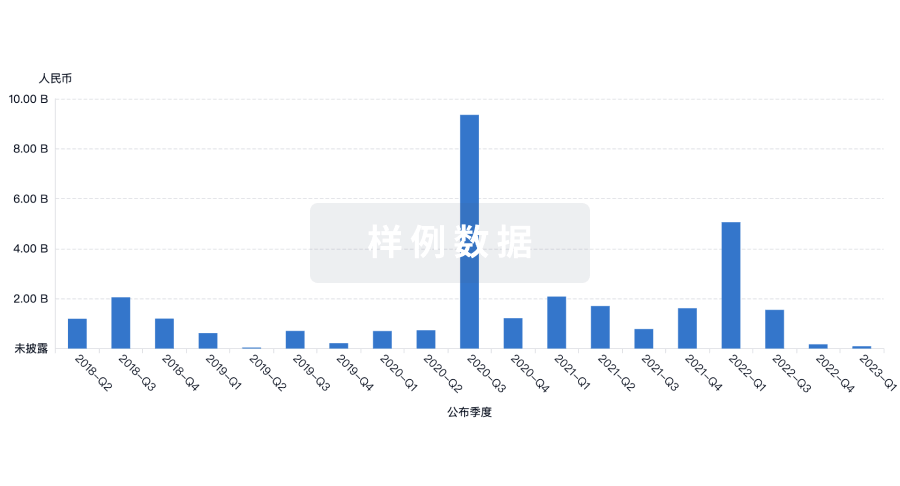

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

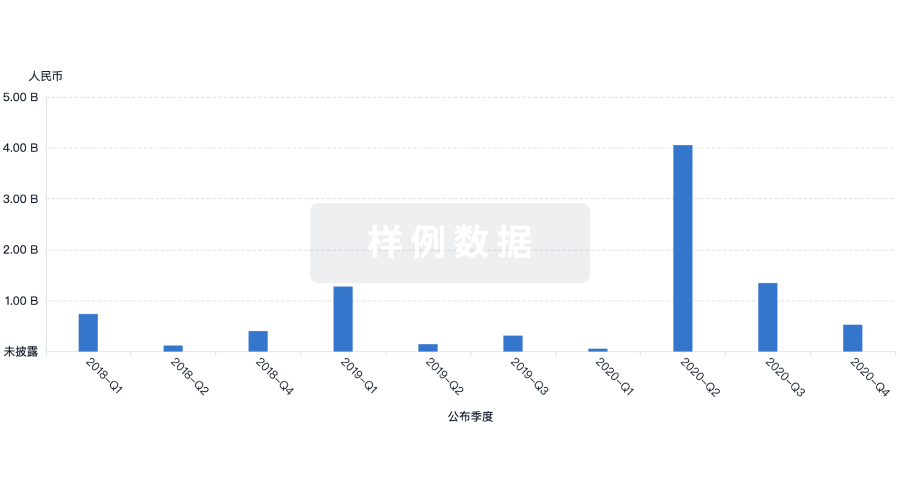

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用