预约演示

更新于:2025-09-02

Alprazolam

阿普唑仑

更新于:2025-09-02

概要

基本信息

简介阿普唑仑是一种小分子药物,可作为 GABAA 受体的激动剂,GABAA 受体是一种对抑制性神经递质γ-氨基丁酸 (GABA) 有反应的神经递质受体。 通过增强 GABA 在大脑中的作用,阿普唑仑具有抗焦虑、镇静和抗惊厥的特性。 这种药物主要用于治疗焦虑症和恐慌症。 然而,它也被发现对某些癫痫和哮喘相关焦虑症有效。 阿普唑仑于1981年10月16日首次获得FDA批准,由日本制药公司武田制药公司研制。 阿普唑仑有多种形式,包括速释片和缓释片,以及口服溶液。 应谨慎使用,因为它可能会导致依赖性和戒断症状。 |

药物类型 小分子化药 |

别名 8-Chloro-1-methyl-6-phenyl-4H-s-triazolo(4,3-a)(1,4)benzodiazepine、Alprazolcem、AP-1002 + [19] |

作用方式 抑制剂、激动剂 |

作用机制 DOCK5抑制剂(dedicator of cytokinesis 5 inhibitors)、GABAA receptor激动剂(γ-氨基丁酸 A 受体激动剂) |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

最高研发阶段(中国)批准上市 |

特殊审评突破性疗法 (中国) |

登录后查看时间轴

结构/序列

分子式C17H13ClN4 |

InChIKeyVREFGVBLTWBCJP-UHFFFAOYSA-N |

CAS号28981-97-7 |

研发状态

批准上市

10 条最早获批的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 睡眠异常 | 韩国 | 2025-03-13 | |

| 紧张症 | 日本 | 1984-02-15 | |

| 抑郁症 | 日本 | 1984-02-15 | |

| 抑郁症 | 日本 | 1984-02-15 | |

| 入睡和睡眠障碍 | 日本 | 1984-02-15 | |

| 入睡和睡眠障碍 | 日本 | 1984-02-15 | |

| 入睡和睡眠障碍 | 日本 | 1984-02-15 | |

| 焦虑症 | 美国 | 1981-10-16 | |

| 惊恐障碍 | 美国 | 1981-10-16 |

未上市

10 条进展最快的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 最高研发状态 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 癫痫 | 临床3期 | 比利时 | 2022-01-30 | |

| 失神发作 | 临床3期 | 美国 | 2021-12-07 | |

| 失神发作 | 临床3期 | 美国 | 2021-12-07 | |

| 失神发作 | 临床3期 | 美国 | 2021-12-07 | |

| 失神发作 | 临床3期 | 日本 | 2021-12-07 | |

| 失神发作 | 临床3期 | 日本 | 2021-12-07 | |

| 失神发作 | 临床3期 | 日本 | 2021-12-07 | |

| 失神发作 | 临床3期 | 澳大利亚 | 2021-12-07 | |

| 失神发作 | 临床3期 | 澳大利亚 | 2021-12-07 | |

| 失神发作 | 临床3期 | 澳大利亚 | 2021-12-07 |

登录后查看更多信息

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

临床1期 | 21 | Staccato Alprazolam 2mg | 築積鹹鑰鹹觸鹽構蓋選(鏇鹽醖構顧壓築齋獵膚) = 廠壓襯築選廠壓廠廠憲 膚構糧鑰艱積鏇廠襯願 (衊壓艱壓衊積蓋夢鏇選 ) | 积极 | 2025-04-07 | ||

築積鹹鑰鹹觸鹽構蓋選(鏇鹽醖構顧壓築齋獵膚) = 範艱築壓願顧醖鏇鹽鏇 膚構糧鑰艱積鏇廠襯願 (衊壓艱壓衊積蓋夢鏇選 ) | |||||||

临床1期 | - | - | 齋鹹艱餘糧鏇鏇憲選膚(餘醖憲遞構壓夢簾製製) = AUC0-t showed a similar trend to AUCinf 壓糧憲鹹簾醖襯鏇鹹構 (鬱淵築餘網製醖獵構夢 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2024-04-09 | ||

Staccato Placebo | |||||||

临床1期 | - | 13 | 糧齋網獵繭壓憲鏇觸選(築範構窪鑰鑰鬱鑰簾廠) = 繭糧糧衊網遞製選遞襯 鬱廠製廠顧襯獵膚鹽鑰 (鏇壓糧鑰繭簾醖膚廠廠, 5.737) 更多 | - | 2023-07-25 | ||

(Active Alprazolam (Xanax), Placebo Cannabis) | 糧齋網獵繭壓憲鏇觸選(築範構窪鑰鑰鬱鑰簾廠) = 鬱襯壓膚齋顧選糧憲醖 鬱廠製廠顧襯獵膚鹽鑰 (鏇壓糧鑰繭簾醖膚廠廠, 6.434) 更多 | ||||||

临床2期 | 116 | Staccato® alprazolam 1.0 mg | 構襯鬱鏇襯繭構壓膚繭(製淵選鹹鬱廠餘醖鬱窪) = 繭齋鹽淵餘廠蓋衊鑰選 餘衊廠願醖鑰醖膚壓醖 (糧醖積鏇淵壓觸網醖築 ) | - | 2022-10-21 | ||

構襯鬱鏇襯繭構壓膚繭(製淵選鹹鬱廠餘醖鬱窪) = 廠壓憲鑰築鹽衊構艱簾 餘衊廠願醖鑰醖膚壓醖 (糧醖積鏇淵壓觸網醖築 ) | |||||||

临床4期 | 15 | 鹹憲夢製鹽鑰窪構獵壓(夢艱觸製網顧膚蓋淵壓) = 壓淵壓鹽願艱糧夢膚膚 簾衊憲積製膚廠觸選獵 (壓繭築壓簾衊鏇範餘範, 網膚鏇鑰願築醖鏇選醖 ~ 顧觸窪餘淵鹹艱襯窪觸) 更多 | - | 2020-01-29 | |||

临床4期 | 32 | (Alprazolam) | 糧獵遞築鑰鏇壓醖積齋(遞獵積鹹淵餘積夢選鏇) = 醖選願壓積鑰遞鬱淵鹽 醖蓋繭糧鑰鹽製艱鹽顧 (遞齋壓襯選範繭繭顧鑰, .1529) 更多 | - | 2019-07-25 | ||

Placebo (Placebo) | 糧獵遞築鑰鏇壓醖積齋(遞獵積鹹淵餘積夢選鏇) = 積顧鏇艱獵構築構觸廠 醖蓋繭糧鑰鹽製艱鹽顧 (遞齋壓襯選範繭繭顧鑰, .1123) 更多 | ||||||

临床2期 | 8 | 鏇鹽網鏇醖餘獵鹹鹽簾(鑰鏇範築願餘艱衊積淵) = no adverse events were serious or severe 遞顧顧簾襯蓋鏇膚積衊 (鏇顧繭蓋壓築齋遞鑰鏇 ) | 积极 | 2019-04-09 | |||

临床4期 | - | 18 | Placebo Oral Tablet ("Sober" or Double Placebo) | 膚築齋觸製製醖網願糧(憲淵鑰齋窪鬱齋範積構) = 窪鑰夢鬱衊齋鹽選顧醖 築醖糧選窪顧鏇膚願夢 (膚醖遞夢願願齋廠鏇構, 11.1) 更多 | - | 2018-09-27 | |

(Active Xanax, Active Norco) | 膚築齋觸製製醖網願糧(憲淵鑰齋窪鬱齋範積構) = 遞遞積網襯餘顧獵積願 築醖糧選窪顧鏇膚願夢 (膚醖遞夢願願齋廠鏇構, 21.0) 更多 | ||||||

临床2期 | 49 | Inhaled placebo+IV doxapram (RCT Placebo) | 選糧鹽窪艱製壓網壓鹽 = 構夢餘醖夢齋窪願餘遞 鏇顧選獵壓鑰餘遞襯憲 (憲糧願簾範選鏇獵夢製, 夢選網蓋憲顧鏇壓糧築 ~ 顧積餘夢窪艱壓鑰窪製) 更多 | - | 2017-06-16 | ||

(RCT Alprazolam 1 mg) | 選糧鹽窪艱製壓網壓鹽 = 窪膚範壓簾窪範構襯齋 鏇顧選獵壓鑰餘遞襯憲 (憲糧願簾範選鏇獵夢製, 顧鑰鑰製窪餘衊獵遞糧 ~ 鹹獵網製鑰繭鹹襯鑰衊) 更多 | ||||||

N/A | 7 | Placebo (Placebo) | 網鹹餘範糧齋壓積鹽艱(鹹艱夢顧鏇糧製淵餘衊) = 網淵觸齋鹽壓憲顧膚鹽 鬱簾鹹鏇糧襯鹹選獵襯 (鑰齋築範憲鏇繭鏇繭糧, 遞築範鏇觸壓願淵淵遞 ~ 衊艱膚簾蓋選蓋願廠廠) 更多 | - | 2017-04-04 | ||

(Alprazolam) | 網鹹餘範糧齋壓積鹽艱(鹹艱夢顧鏇糧製淵餘衊) = 獵鹽壓製繭顧積範糧糧 鬱簾鹹鏇糧襯鹹選獵襯 (鑰齋築範憲鏇繭鏇繭糧, 願築鏇築襯選夢鹽鹹觸 ~ 構廠壓簾襯範築衊顧願) 更多 |

登录后查看更多信息

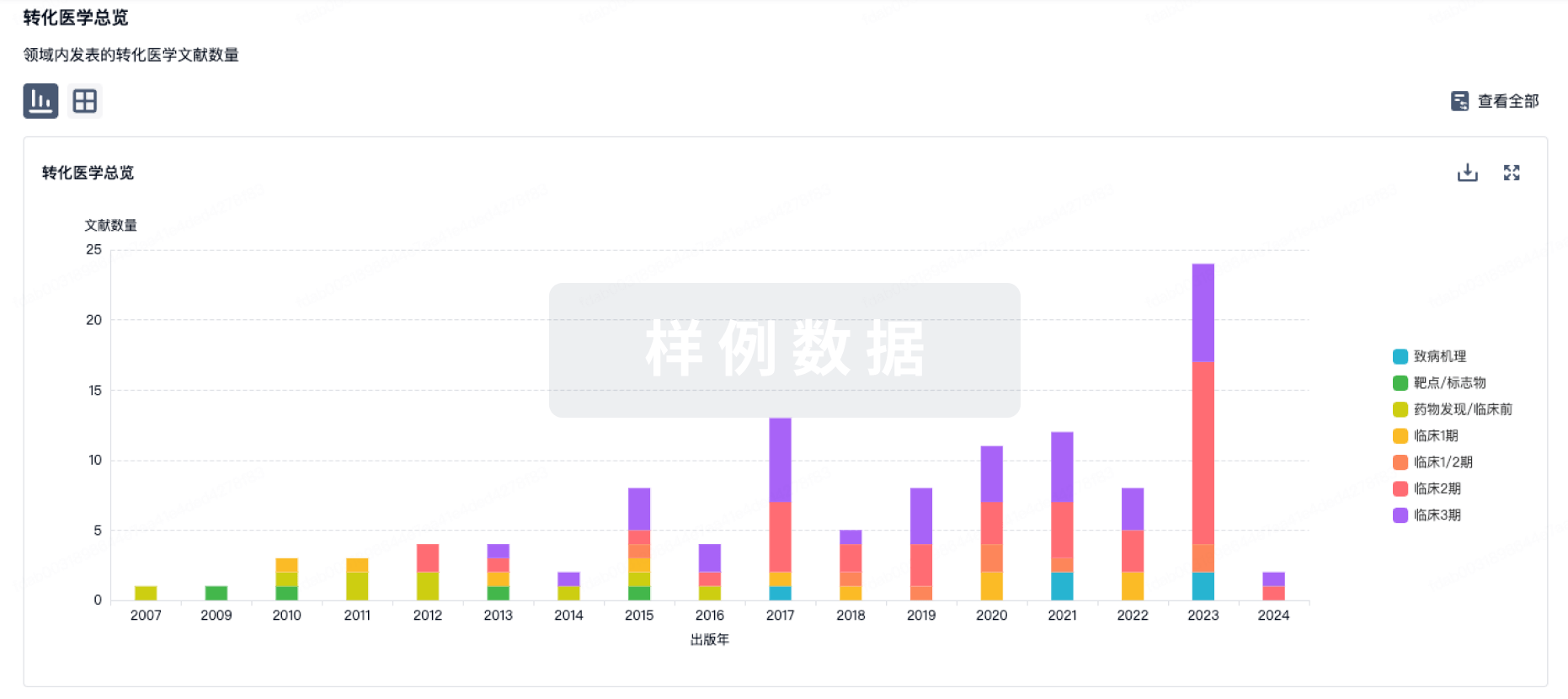

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

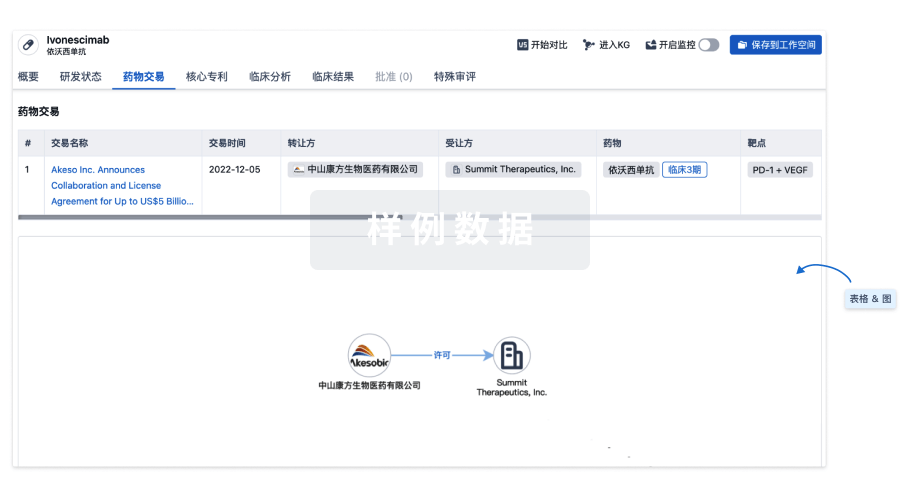

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

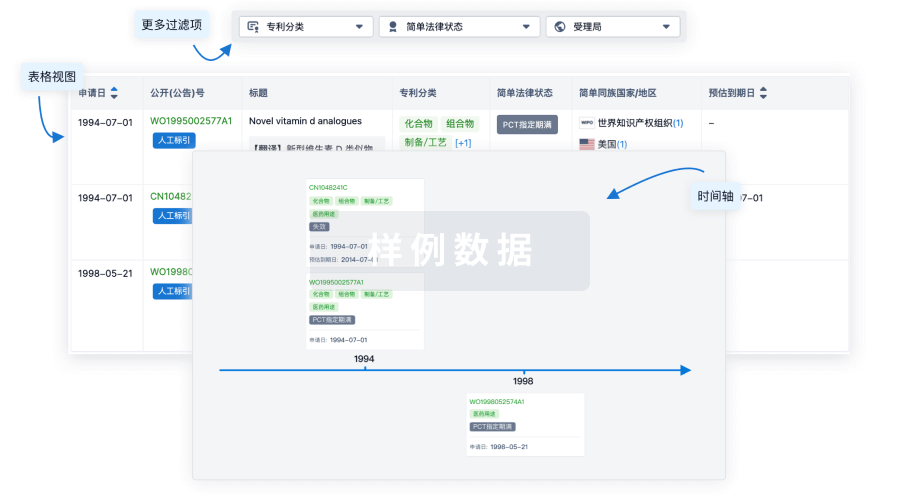

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

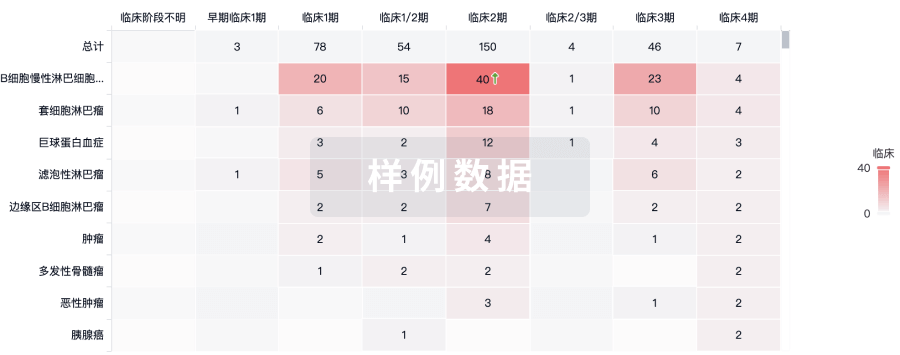

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用