预约演示

更新于:2025-09-09

Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd.

更新于:2025-09-09

概览

标签

皮肤和肌肉骨骼疾病

免疫系统疾病

感染

小分子化药

单克隆抗体

合成多肽

疾病领域得分

一眼洞穿机构专注的疾病领域

暂无数据

技术平台

公司药物应用最多的技术

暂无数据

靶点

公司最常开发的靶点

暂无数据

| 排名前五的药物类型 | 数量 |

|---|---|

| 小分子化药 | 64 |

| 合成多肽 | 7 |

| 单克隆抗体 | 5 |

| 诊断用放射药物 | 2 |

| 非降解型分子胶 | 1 |

关联

78

项与 Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. 相关的药物靶点 |

作用机制 GLP-1R激动剂 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 澳大利亚 |

首次获批日期2025-03-06 |

靶点 |

作用机制 PDL1抑制剂 [+2] |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 美国 |

首次获批日期2024-12-13 |

作用机制 JAK1抑制剂 [+1] |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 美国 |

首次获批日期2024-07-25 |

513

项与 Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. 相关的临床试验NCT07144852

Randomized, Multi-Center, Evaluator-Blind, Vehicle-Controlled Study to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety of Reformulated Levulan Kerastick Plus Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) for Field-Directed Treatment in Patients With Actinic Keratosis (AK) of Upper Extremities

This Phase 3, randomized, multi-center, evaluator-blind, vehicle-controlled study evaluates the efficacy and safety of reformulated Levulan Kerastick (aminolevulinic acid HCl 20%) combined with photodynamic therapy (PDT) for field-directed treatment of actinic keratosis (AK) on the upper extremities. Approximately 260 adult patients with 4-8 mild to moderate AK lesions on one arm will be randomized to receive either active treatment or vehicle control, followed by exposure to blue light. During the study, up to 2 PDT sessions may be administered depending on the clearance of lesions. The primary endpoint is complete clearance rate (CCR) at Week 12. Secondary endpoints include AK clearance rate (AKCR), partial clearance, change in total lesion count and area, recurrence rate, cosmetic response, and patient satisfaction. Safety assessments include adverse events, local skin reactions, vital signs, and lab tests.

开始日期2025-09-01 |

NCT07144345

Randomized, Multi-Center, Evaluator-Blind, Vehicle-Controlled Study to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety of Reformulated Levulan Kerastick Plus Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) for Field-Directed Treatment in Patients With Actinic Keratosis (AK) of Face and (Bald) Scalp

This Phase 3, randomized, multi-center, evaluator-blind, vehicle-controlled study evaluates the efficacy and safety of reformulated Levulan Kerastick (aminolevulinic acid HCl 20%) combined with photodynamic therapy (PDT) for field-directed treatment of actinic keratosis (AK) on the face or bald scalp. Approximately 160 adult patients with 4-8 mild to moderate AK lesions will be randomized into four treatment arms based on two variables: type of treatment (active drug or vehicle) and incubation time. During the study, up to 2 PDT sessions may be administered depending on the clearance of lesions. The primary endpoint is complete clearance rate (CCR) at Week 12. Secondary endpoints include AK clearance rate (AKCR), partial clearance, change in total lesion count and area, recurrence rate, cosmetic response, and patient satisfaction. Safety assessments include adverse events, local skin reactions, vital signs, and lab tests.

开始日期2025-09-01 |

NCT07133308

A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Multicenter Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Deuruxolitinib in Adolescent Patients With Severe Alopecia Areata With an Open-label Extension Period

This study evaluates the safety and effectiveness of deuruxolitinib in adolescents aged 12 to less than 18 years who have 50% or greater scalp hair loss.

开始日期2025-08-05 |

100 项与 Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

431

项与 Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. 相关的文献(医药)2025-09-01·Dermatology and Therapy

Reduction in Facial Sebum Production Following Treatment with Clascoterone Cream 1% in Patients with Acne Vulgaris: 12-Week Interim Analysis.

Article

作者: Kyeremateng, Kizito ; Squittieri, Nicholas ; Draelos, Zoe D

INTRODUCTION:

In vitro, clascoterone inhibits androgen-induced sebum production-a key driver of acne pathogenesis-although the exact mechanism of action of clascoterone for the treatment of acne is unknown. This study evaluated reductions in casual sebum production following 12 weeks of clascoterone cream 1% treatment in patients with acne.

METHODS:

Patients ≥ 12 years old with mild-to-moderate acne applied clascoterone cream 1% twice daily for 12 weeks. The primary endpoint was the reduction in casual sebum measurements at Week 12. Additional endpoints included Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) score, inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts (ILC and NILC), and tolerability. Data were analyzed using Student's t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

RESULTS:

Forty patients with a mean age of 20.9 years were enrolled, all of whom completed Week 12. Significant percentage reductions from baseline were observed in sebum measurements (27%), ILC (54%), and NILC (34%; all p < 0.001), and patients achieved a 29% reduction in IGA score. No tolerability or safety issues were identified during the 12-week interim analysis period.

CONCLUSION:

Clascoterone cream 1% led to significant reductions in sebum measurements with improvements in acne severity and was well tolerated.

TRIAL REGISTRATION:

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT06415279.

2025-09-01·Drugs-Real World Outcomes

Assessment of Burden of Partial Response to Standard Doses of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Patients with Clinically Diagnosed Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Real-World Evidence Study in India

Article

作者: Peri, Soujanya ; Mane, Amey ; Dharmadhikari, Shruti ; Saikia, Rajiv ; Markandeywar, Neeraj ; Khandhedia, Chintan ; Garje, Yogesh ; Joglekar, Sadhna ; Mehta, Suyog ; Gupta, Sunil ; Sharma, Praveen ; Satpathy, Ashwini

BACKGROUND:

Partial response to standard-dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is common, yet real-world data on its burden and management in Indian settings remain limited.

OBJECTIVE:

This study aimed to understand the burden, clinical profile, drug utilization patterns across specialties, the effectiveness of Pantoprazole 80 mg dual delayed-release (DDR) formulation, and management strategies used in the treatment of partial responders with clinically diagnosed GERD in Indian settings.

METHODS:

This was a multicentric, retrospective observational study. Data on adult patients with GERD with a follow-up duration of at least 4 weeks from baseline were extracted from electronic medical records (EMR) of outpatient settings from five centers, which included drug utilization patterns, clinical and treatment profiles, and effectiveness of PPIs.

RESULTS:

Among EMRs of 5205 patients with GERD, 38.0% were on rabeprazole and 36.6% on pantoprazole (mean age: 53.3 years; standard deviation: 14.3 years), and 55.0% were male. Heartburn was the primary complaint in 76.0% of cases. Cardiovascular co-morbidities with dyslipidemia were reported in 66.7% (1742/2610) patients. Pantoprazole and rabeprazole were preferred across specialties, where 31.1% (592/1906) and 17.7% (350/1979) adhered to treatment, respectively. Total burden of partial responders was 41.7%, including patients who switched PPIs, changed PPI dosage, or added other medications. Pantoprazole 40 mg twice daily (BD) showed 49.1% improvement in heartburn and 50.9% in abdominal pain. Pantoprazole 80 mg DDR once daily demonstrated significantly higher symptom relief, with a 60.2% reduction in heartburn (p < 0.001) and a 66.1% reduction in abdominal pain (p < 0.001). These findings suggest that higher-dose pantoprazole therapy may be a clinically effective strategy for managing partial responders to standard-dose PPIs.

CONCLUSIONS:

A significant proportion of patients with GERD were partial responders to PPIs. Pantoprazole and rabeprazole had high patient adherence across disciplines. Both pantoprazole DDR 80 mg once daily (OD) and 40 mg BD demonstrated significant symptom reduction in partial responders, supporting their use in optimizing GERD management in Indian clinical settings.

2025-08-18·BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Efficacy and safety of tildrakizumab in patients with early- vs. late-onset psoriasis

Article

作者: Blauvelt, Andrew ; Gogineni, Ranga ; Armstrong, April W ; Lebwohl, Mark ; Asahina, Akihiko ; Griffiths, Christopher E M

Abstract:

Background:

The age of psoriasis onset is bimodally distributed with distinct peaks at < 40 (early onset) and ≥ 40 years (late onset) of age. Although the age of psoriasis onset is associated with distinct disease profiles, few well-controlled studies have reported the efficacy of biologics in patients with early- vs. late-onset disease. The efficacy and safety of tildrakizumab, an interleukin-23 p19 inhibitor, for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis were investigated in the reSURFACE 1 (NCT01722331) and reSURFACE 2 (NCT01729754) phase III trials.

Objectives:

To determine the efficacy and safety of tildrakizumab in patients with early- vs. late-onset psoriasis through 28 weeks of treatment.

Methods:

This was a post hoc subgroup analysis of patients from reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2. Patients aged ≥ 50 years were grouped by age of psoriasis onset (< 40 years vs. ≥ 40 years). Efficacy endpoints included absolute Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and the proportions of patients who achieved a ≥ 75%, ≥ 90% or 100% improvement from baseline in PASI (PASI 75, PASI 90 and PASI 100, respectively), a Physician Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (PGA 0/1) and DLQI of 0 or 1 (DLQI 0/1), adjusted for potential confounders. Safety was assessed based on treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs).

Results:

Higher percentages and adjusted responder rate estimates of patients with late- (n = 130) vs. early-onset (n = 111) psoriasis achieved an absolute PASI < 1 (36.2% vs. 27.9%; estimate was 32.2% vs. 25.0%), PASI 90 (50.8% vs. 39.6%; estimate was 49.4% vs. 40.2%) and PASI 100 (21.5% vs. 8.1%; estimate was 13.7% vs. 7.9%) at week 28 (all P < 0.05). Age of onset did not significantly affect change from baseline in absolute PASI or DLQI, or the achievement of PASI < 5, PASI < 3, PASI 75, DLQI 0/1 or PGA 0/1 (all P > 0.05). Efficacy findings were supported in a subset of patients matched by disease duration. TEAEs and serious TEAEs occurred in 65.8% vs. 66.2% and 3.6% vs. 6.9% of patients with early- vs. late-onset psoriasis, respectively.

Conclusions:

Treatment with tildrakizumab was effective with no safety signals found in either of the patient subgroups. Patients with late-onset psoriasis were more likely to achieve complete or near-complete clearance than patients with early-onset psoriasis.

894

项与 Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. 相关的新闻(医药)2025-09-09

New Delhi: The Indian pharmaceutical industry requires price increases, site and intellectual property (IP) transfers to deal with the prevailing uncertainty in the sector amid US tariffs, according to a report by Systematix Research.

The report highlighted that tariff uncertainty continues to prevail, with companies unwilling to add capacities in the US.

It stated, "Price increase, site and IP transfers are the three tools the industry requires to deal with the tariffs."

At the same time, raw material prices are correcting sharply in certain categories, particularly antibiotics, while customers are destocking to take advantage of lower prices. Overall, generic API prices have stabilized.

The report further noted that companies remain hopeful yet cautious around new growth avenues and product launches, which could help them offset the erosion in high-value launches.

On the CDMO front, requests for proposals (RFPs) for custom synthesis and CDMO services remain strong. Multiple companies are also eyeing GLP-1 opportunities in India and emerging markets, preparing for a day-one launch.

Meanwhile, firms continue to cautiously evaluate inorganic growth opportunities. Demand for anti-infectives in domestic markets remained weak during the quarter, while building over-the-counter (OTC) platforms continues to be a key focus area.

On the earnings front, the report stated that 1QFY26 was weak, with underperformers outnumbering outperformers. Most players recorded mid-to-high single-digit growth in India pharma (organic). However, the US geography witnessed margin pressures, as price erosion began.

Among the outperformers,

Sun Pharma

(SUNP) exceeded expectations due to lower operational costs. India business was strong, but US generics came in weaker than expected.

Pfizer

(PFIZ) saw growth returning at 7 percent, which along with lower operational costs, helped it outperform.

Similarly, Syngene (SLPA) generated higher-than-expected contribution from licensing income, leading to stronger margins.

On the weaker side,

Orchid Pharma

(ORCP) was impacted by an adverse hit on industry-wide cephalosporin API volumes, likely due to customer inventory destocking in anticipation of price correction.

Piramal Pharma

(PLM) faced heavy pressure on its export business due to dumping by China.

Dr. Reddy's Laboratories

(DRRD) saw weakness in its high-value US generic business, which impacted margins.

Divi's Laboratories

(DIVI) reported in-line revenue but with slightly weak margins.

The report concluded that the Indian pharma sector continues to face near-term uncertainty, though companies are positioning themselves for long-term growth opportunities.

2025-09-08

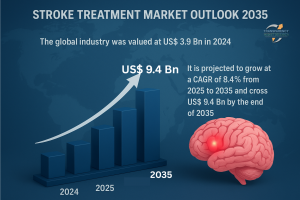

Stroke Treatment Market to Expand from USD 3.9 Billion in 2024 to USD 9.4 Billion by 2035 Driven by Rising Global Stroke Incidence -Transparency Market Research

Global Stroke Treatment Market to Achieve USD 9.4 Billion by 2035 as Healthcare Systems Focus on Neurological Care”

— Latest Report by Transparency Market Research, Inc.

WILMINGTON, DE, UNITED STATES, September 8, 2025 /

EINPresswire.com

/ --

Stroke Treatment Market

Outlook 2035

The global stroke treatment market is poised for strong growth, supported by rising prevalence of stroke cases, advancements in treatment therapies, and increasing healthcare investments. Valued at US$ 3.9 Bn in 2024, the industry is forecast to grow at a CAGR of 8.4% from 2025 to 2035, reaching over US$ 9.4 Bn by 2035. Expanding access to advanced neurovascular devices and growing emphasis on early intervention are key drivers of this growth.

Don't miss out on the Latest Market Intelligence. Get your Sample Report Copy Today@

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/sample/sample.php?flag=S&rep_id=73917

Industry Overview

Stroke treatment involves the use of drugs, medical devices, and therapeutic procedures to restore blood flow, minimize brain damage, and enhance patient recovery. With stroke being a major public health burden, increasing awareness campaigns and investments in healthcare infrastructure are propelling the adoption of effective treatment solutions.

The growing demand for thrombolytic drugs, mechanical thrombectomy devices, and rehabilitation therapies is shaping the industry’s growth. Furthermore, the integration of AI-based diagnostic imaging, telemedicine, and precision medicine is revolutionizing stroke management.

Analysis of Key Players in the Stroke Treatment Market

The stroke treatment market is highly competitive, with several global pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies playing a key role.

Leading players include

• Bristol-Myers Squibb Company

• Sanofi

• F. Hoffmann-La Roche (Genentech)

• Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited

• AstraZeneca

• Biogen Inc.

• Johnson & Johnson Services, Inc.

• Bayer AG

• Eli Lilly and Company

• Mylan

• Teva Pharmaceuticals

• Zydus Cadila

• Sun Pharmaceutical

These companies have been profiled in the stroke treatment market research report on the basis of parameters such as company overview, financial performance, business strategies, product portfolio, business segments, and recent developments.

Key Developments in the Stroke Treatment Market

• October 2024 – Royal Philips announced a collaboration with Medtronic Neurovascular to improve awareness and expand access to timely stroke diagnosis and treatment solutions.

• February 2024 – Basking Biosciences, a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical firm focused on novel acute thrombolytic therapies for stroke, completed a US$ 55 million financing round. The investment was led by ARCH Venture Partners, with participation from Insight Partners, Platanus, Solas BioVentures, and RTW Investments, along with existing investors including Longview Ventures, Rev1 Ventures, and The Ohio State University.

Key Growth Drivers

1. Rising Global Stroke Incidence – Increasing cases due to aging populations, hypertension, and diabetes.

2. Advancements in Medical Devices – Mechanical thrombectomy and clot retrieval devices improving survival rates.

3. Drug Innovation – Development of novel anticoagulants and thrombolytics enhancing treatment efficiency.

4. Telemedicine & AI Diagnostics – Early detection and faster treatment decisions through advanced imaging and digital health tools.

5. Government & NGO Initiatives – Stroke awareness campaigns and healthcare funding boosting accessibility.

Discuss Implications for Your Industry Request Sample Research PDF@

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/sample/sample.php?flag=S&rep_id=73917

Market Restraints & Challenges

• High Treatment Costs – Advanced therapies and devices remain expensive.

• Limited Access in Developing Regions – Lack of stroke-ready hospitals and trained professionals.

• Risk of Side Effects – Certain anticoagulants and thrombolytic drugs pose bleeding risks.

• Regulatory Barriers – Lengthy approval processes for new drugs and devices.

Market Segmentation

By Treatment Type

• Medication (Anticoagulants, Antiplatelets, Thrombolytics, Others)

• Surgery & Endovascular Procedures

• Rehabilitation Therapy

By Stroke Type

• Ischemic Stroke

• Hemorrhagic Stroke

• Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA)

By End User

• Hospitals

• Specialty Clinics

• Ambulatory Surgical Centers

• Rehabilitation Centers

By Region

• North America

• Europe

• Asia-Pacific

• Latin America

• Middle East & Africa

Market Trends & Innovations

1. AI-Powered Stroke Diagnosis – Faster and more accurate imaging-based decisions.

2. Minimally Invasive Stroke Surgeries – Increasing adoption of advanced thrombectomy devices.

3. Personalized Medicine – Genetic profiling aiding targeted treatment approaches.

4. Stroke Rehabilitation Robotics – Enhancing post-stroke recovery outcomes.

5. Collaborations & Clinical Trials – Partnerships among pharma and medtech firms to expand therapeutic options.

Why Invest in This Report?

• Accurate market size and CAGR projections through 2035.

• In-depth insights into growth drivers, restraints, and opportunities.

• Competitive analysis of global players and their innovation strategies.

• Emerging opportunities across high-growth regions and therapeutic areas.

• Coverage of regulatory and reimbursement frameworks.

Future Outlook

The global stroke treatment market is projected to reach US$ 9.4 Bn by 2035, driven by the growing prevalence of stroke cases, innovations in treatment methods, and improved accessibility to healthcare.

Future trends shaping the market include:

• Smart wearable devices for early detection and prevention.

• AI-integrated imaging platforms for quicker clinical decision-making.

• Regenerative medicine & stem-cell therapies as potential future stroke treatments.

• Expansion in emerging markets, increasing affordability and access.

To buy this comprehensive market research report, click here to inquire@

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/checkout.php?rep_id=73917<ype=S

Important FAQs with Answers

Q1. What was the global market size of stroke treatment in 2024?

A1. The market was valued at US$ 3.9 Bn in 2024.

Q2. What is the projected market size by 2035?

A2. The market is expected to surpass US$ 9.4 Bn by 2035.

Q3. What is the CAGR for 2025–2035?

A3. The industry is projected to grow at a CAGR of 8.4%.

Q4. What are the main treatment types?

A4. Medications, surgery & endovascular procedures, and rehabilitation therapies.

Q5. Who are the key players in the market?

A5. Leading companies include Medtronic, Johnson & Johnson, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Abbott, and Bristol Myers Squibb.

Q6. What innovations are shaping the future of stroke treatment?

A6. Key innovations include AI-powered imaging, thrombectomy devices, smart wearables, and regenerative therapies.

Related Links

• Neuroregeneration Therapy Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/neuroregeneration-therapy-market.html

• Aldosterone Receptor Antagonists Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/aldosterone-receptor-antagonists-market.html

• Vasopressin Antagonists Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/vasopressin-antagonists-market.html

• Parkinson’s Disease Therapeutics Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/parkinsons-disease-therapeutics-market.html

• Alzheimer’s Drugs Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/alzheimers-drugs-market.html

• Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/alzheimers-disease-biomarkers-market.html

• Multiple Sclerosis Drugs Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/multiple-sclerosis-drugs.html

• Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/amyotrophic-lateral-sclerosis.html

• Hormone Replacement Therapy Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/hormone-replacement-therapy-market.html

• Neurology Devices Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/neurology-devices-market.html

• Neuromodulation Devices Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/global-neuromodulation-devices-market.html

• Neurotherapeutic Drugs Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/neurotherapeutic-drugs-market.html

• Neuromorphic Chip Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/neuromorphic-chip-market.html

• Neurovascular Stent Retriever Technology Market -

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/neurovascular-stent-retrievers-market.html

About Us Transparency Market Research

Transparency Market Research, a global market research company registered at Wilmington, Delaware, United States, provides custom research and consulting services. The firm scrutinizes factors shaping the dynamics of demand in various markets. The insights and perspectives on the markets evaluate opportunities in various segments. The opportunities in the segments based on source, application, demographics, sales channel, and end-use are analysed, which will determine growth in the markets over the next decade.

Our exclusive blend of quantitative forecasting and trends analysis provides forward-looking insights for thousands of decision-makers, made possible by experienced teams of Analysts, Researchers, and Consultants. The proprietary data sources and various tools & techniques we use always reflect the latest trends and information. With a broad research and analysis capability, Transparency Market Research employs rigorous primary and secondary research techniques in all of its business reports.

Contact Us

Transparency Market Research Inc.

CORPORATE HEADQUARTER DOWNTOWN,

1000 N. West Street,

Suite 1200, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 USA

Tel: +1-518-618-1030

USA - Canada Toll Free: 866-552-3453

Atil Chaudhari

Transparency Market Research Inc.

+ +1 518-618-1030

email us here

Visit us on social media:

LinkedIn

YouTube

X

Other

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability

for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this

article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

2025-09-08

Mumbai: Advancing its PD-LI plans,

Glenmark Pharmaceuticals

has announced the initiation of the Phase 3 trial for its lung cancer therapy

Envafolimab

, across multiple sites including India.

The clinical program is designed to assess the efficacy, safety, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity of Envafolimab in patients with resectable Stage IIIA and IIIB

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

(NSCLC) in the adjuvant setting.

“By advancing this trial across multiple geographies, we are reinforcing our commitment to transforming the standard of care in Stage III NSCLC and addressing one of the greatest unmet needs in

cancer treatment

today,” said Dr Monika Tandon, Global Head of Clinical Development, Glenmark Pharmaceuticals.

Glenmark has also submitted a

Clinical Trial

Application (CTA) in Russia and is preparing to open additional clinical trial sites in Brazil and Mexico to further expand the global footprint of the multi-nation study.

Envafolimab, a novel anti-PD-L1 inhibitor, a key checkpoint protein expressed by various tumours. By blocking its interaction with PD-1 receptors, it enables T-cell activation, leading to an anti-tumor immune response.

Invented by Alphamab Oncology, the

immunotherapy

was co-developed by 3D Medicines Inc and the

Indian drugmaker

licensed its India, Latin America among several other market development and market rights in 2024.

The license agreement outlined a consideration of a “low double-digit million US dollar amount up to launch, along with a “triple-digit million US dollar milestone payments” with a royalty fee of single-to-double-digits percentage according to the level of net sales.

In 2021, the Chinese regulator approved Envafolimab brand ‘Enwedia’ for the treatment of advanced unresectable or metastatic solid tumors (MSI-H) and since December 2023 the therapy is further investigated in a Phase 3 study for NSLC sponsored by 3D Medicines Inc in China.

PD-LI therapies once part of big pharma portfolio are gaining a strong traction among Indian drugmakers and a standout case is Unloxcyt—an onco-derma drug approved by the FDA for advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma— acquired by Sun Pharma as part of its $355 million deal to buy the therapy owner Checkpoint Therapeutics.

By

Online Bureau

,

临床3期引进/卖出免疫疗法上市批准

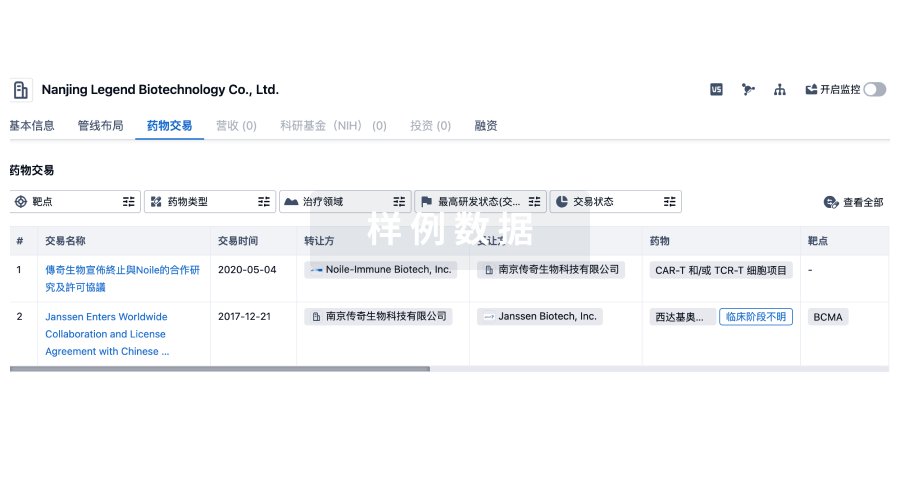

100 项与 Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

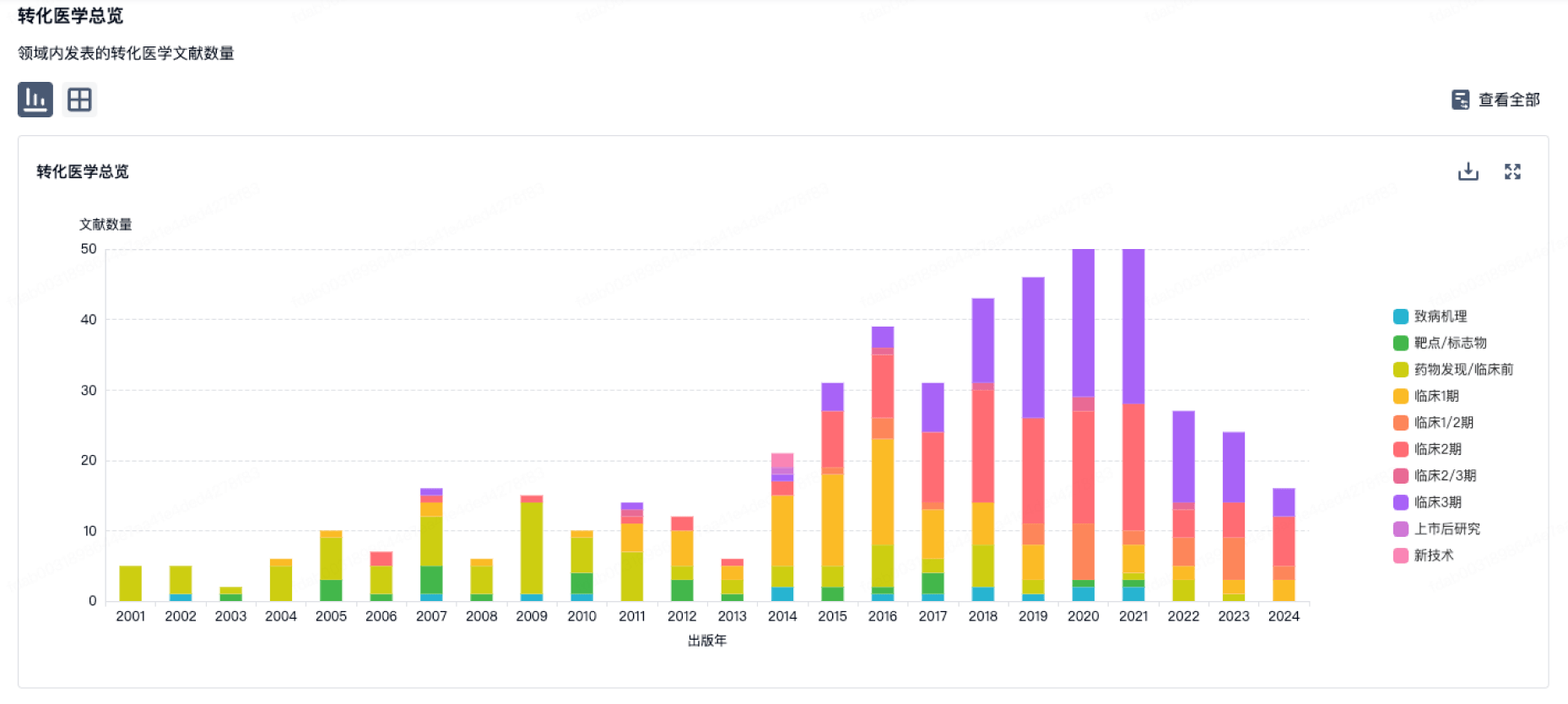

100 项与 Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

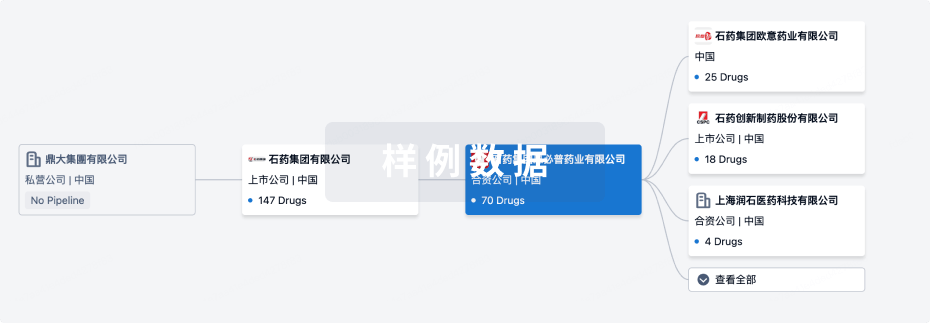

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2025年09月15日管线快照

管线布局中药物为当前组织机构及其子机构作为药物机构进行统计,早期临床1期并入临床1期,临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

药物发现

4

2

临床前

临床申请批准

1

2

临床1期

临床2期

1

1

申请上市

批准上市

67

127

其他

登录后查看更多信息

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

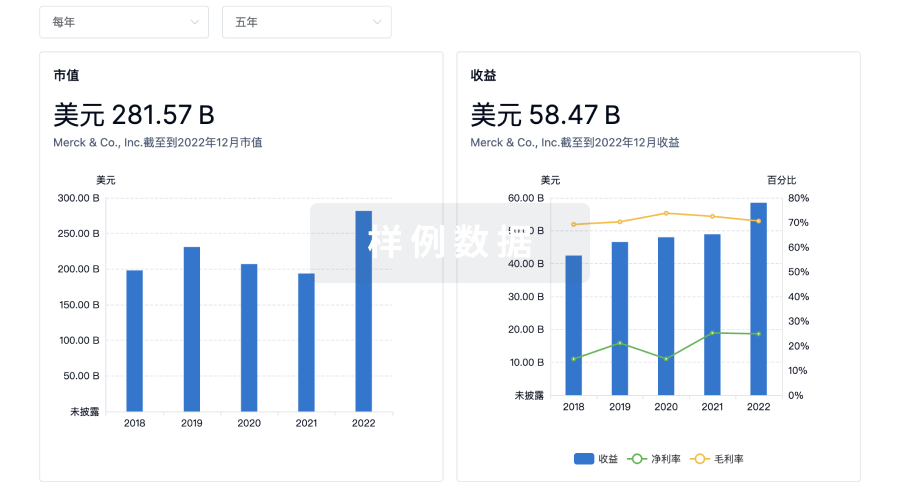

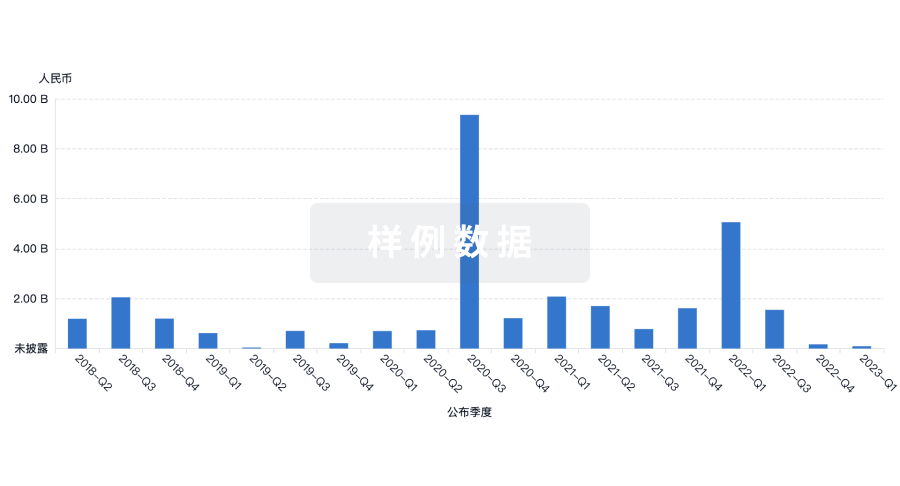

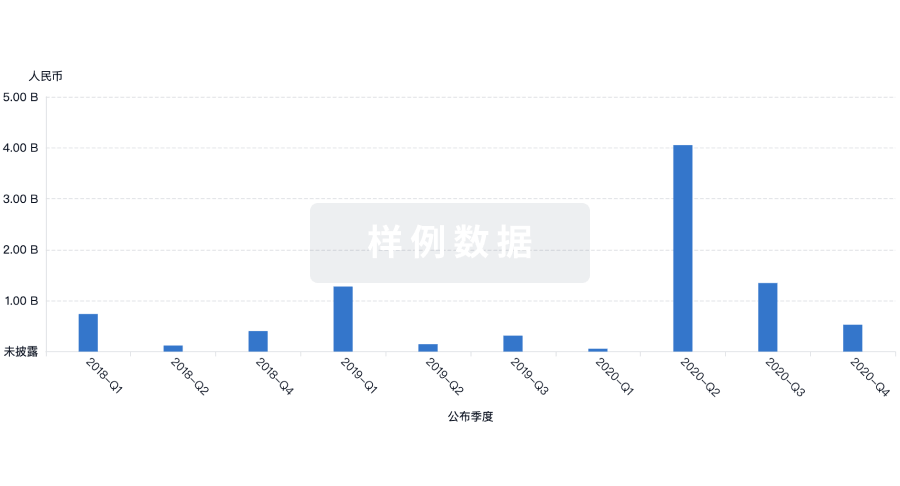

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

Eureka LS:

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用