预约演示

更新于:2025-08-29

Baxter International, Inc.

更新于:2025-08-29

概览

标签

肿瘤

呼吸系统疾病

其他疾病

小分子化药

灭活疫苗

预防性疫苗

疾病领域得分

一眼洞穿机构专注的疾病领域

暂无数据

技术平台

公司药物应用最多的技术

暂无数据

靶点

公司最常开发的靶点

暂无数据

| 排名前五的药物类型 | 数量 |

|---|---|

| 小分子化药 | 58 |

| 重组凝血因子 | 4 |

| 合成多肽 | 4 |

| 灭活疫苗 | 3 |

| 预防性疫苗 | 3 |

关联

82

项与 Baxter International, Inc. 相关的药物作用机制 TOP1抑制剂 [+1] |

在研机构 |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 日本 |

首次获批日期2024-12-27 |

靶点 |

作用机制 vWFCP调节剂 [+1] |

在研适应症 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 美国 |

首次获批日期2023-11-09 |

靶点 |

作用机制 C5抑制剂 |

在研机构 |

非在研适应症 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 美国 |

首次获批日期2023-08-04 |

202

项与 Baxter International, Inc. 相关的临床试验CTR20250981

一项比较德曲妥珠单抗(优赫得®)联合化疗联合或不联合帕博利珠单抗与化疗联合曲妥珠单抗联合或不联合帕博利珠单抗一线治疗不可切除局部晚期或转移性HER2 阳性胃或胃食管结合部(GEJ)癌受试者的多中心、随机、开放性、III 期 试验(DESTINY-GASTRIC05)

本试验旨在评估德曲妥珠单抗(优赫得,T-DXd,DS-8201a)+氟尿嘧啶+帕博利珠单抗三药联合方案相比SoC 化疗+曲妥珠单抗+帕博利珠单抗一线治疗主队列中不可切除局部晚期或转移性HER2 阳性肿瘤PD-L1 CPS≥1 胃或GEJ 癌受试者的有效性和安全性。一个随机探索性队列进行评估T-DXd+氟尿嘧啶联合治疗相比SoC 化疗+曲妥珠单抗治疗不可切除局部晚期或转移性HER2 阳性肿瘤PD-L1 CPS<1 胃或GEJ 癌受试者的有效性和安全性。

开始日期2025-04-27 |

申办/合作机构 Baxter Oncology GmbH [+2] |

CTR20250279

一项在不适合自体干细胞移植的新诊断多发性骨髓瘤( TI-NDMM ) 受 试 者 中 评 价 belantamab mafodotin 联合来那度胺和地塞米松(BRd)对比达雷妥尤单抗、来那度胺和地塞米松(DRd)的 III期、随机、开放性研究-DREAMM-10

主要目的:在 TI-NDMM 受试者中评价 BRd vs. DRd的临床活性;

关键次要目的:在 TI-NDMM 受试者中进一步评价 BRd vs. DRd 的临床有效性;

次要目的:在 TI-NDMM 受试者中评价 BRd vs. DRd的临床有效性;在 TI-NDMM 受试者中评价 BRd vs. DRd的安全性和耐受性;基于 TI-NDMM 受试者自我报告的症状性不良反应,评价研究治疗的安全性和耐受性;评价并比较 TI-NDMM 受试者的症状及其对功能和 HRQoL 影响的变化;在 TI-NDMM 受试者中表征 belantamab mafodotin 与来那度胺/地塞米松联合给药时 belantamab mafodotin 的暴露量;在 TI-NDMM 受试者中评估 BRd ADA

开始日期2025-03-18 |

申办/合作机构 |

CTR20244119

一项在既往奥希替尼治疗过程中出现疾病进展的EGFR 突变阳性局部晚期或转移性非小细胞肺癌参与者中评估Dato-DXd 联合或不联合奥希替尼治疗对比含铂化疗的III 期、开放性、申办者盲态、随机研究(TROPION-Lung15)

本研究旨在评估 Dato-DXd 联合或不联合奥希替尼对比含铂化疗在既往奥希替尼治疗出现疾病进展的EGFRm 局部晚期或转移性 NSCLC 参与者中的疗效。拟定双主要研究终点旨在证明 Dato-DXd 联合和不联合奥希替尼在盲态独立中心审查(BICR)评估的 PFS 方面相较于化疗的优效性。关键次要有效性终点是OS和CNS PFS。还将评估 Dato-DXd 联合或不联合奥希替尼相较于化疗的安全性和耐受性特征。

开始日期2025-02-05 |

申办/合作机构 AstraZeneca AB [+2] |

100 项与 Baxter International, Inc. 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 Baxter International, Inc. 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

2,381

项与 Baxter International, Inc. 相关的文献(医药)2026-01-01·BIOMATERIALS

Increasing polycation hydrophobicity in mRNA polyplex vaccines enhances the efficacy of humoral and cellular immunity induction

Article

作者: Kimura, Tsuyoshi ; Qiao, Nan ; Fukushima, Shigeto ; Uchida, Satoshi ; Kim, Hyun Jin ; Naito, Mitsuru ; Hori, Mao ; Chang, Heemin ; Suzuki, Mika ; Miyata, Kanjiro ; Ogura, Satomi

Polycation-based mRNA delivery systems, known as polyplexes, hold significant potential for use in mRNA vaccines and therapeutics. However, their performance has been suboptimal in infectious disease vaccines, which require the induction of both humoral and cellular immunity. Herein, we optimized polycation hydrophobicity to maximize the efficacy of humoral and cellular immunity induction, using biodegradable amphiphilic polyaspartamide derivatives as a platform. The side chains of the polymers contain cationic diethylenetriamine (DET) and hydrophobic 2-cyclohexylethyl (CHE) moieties at varying ratios. Increasing the CHE introduction ratio enhanced immunostimulatory adjuvanticity by activating NLRP3 inflammasome pathway, leading to more efficient activation of cultured dendritic cells. Following subcutaneous injection into mice, polyplexes with higher CHE introduction ratios improved protein expression efficiency in the draining lymph nodes and induced robust germinal center responses. Consequently, antibody responses were enhanced with higher CHE introduction ratios in vaccinations targeting a model antigen and the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Furthermore, the vaccination elicited both CD8-positive and CD4-positive T cells in a Th1-skewed manner. In a distribution analysis, protein expression from the delivered mRNA was localized to the injection site and draining lymph nodes, avoiding a safety concern associated with systemic distribution. Collectively, this study demonstrates that the introduction of hydrophobic moieties into polyaspartamide derivatives is an effective and safe strategy to enhance the efficacy of polyplex-based mRNA vaccines targeting infectious diseases.

2025-12-31·RENAL FAILURE

Comparison of middle molecule removal with expanded hemodialysis versus haemodiafiltration among Chinese hemodialysis patients

Article

作者: Zuo, Li ; Keller, Brad ; Chen, Fengling ; Li, Yiwen ; Ji, Jiayao ; Shi, Zhenwei ; Yao, Qiang ; Zhang, Xinzhou ; Gao, Bihu ; Sarkar, Surupa ; Gu, Leyi ; Gan, Liangying ; Li, Wenge ; Lin, Hongli ; Ding, Feng ; Ge, Yongchun

BACKGROUND:

This study aimed to compare uremic toxin removal with expanded hemodialysis against post-dilution online haemodiafiltration therapy in Chinese patients with chronic kidney failure in a single treatment.

METHODS:

This randomized, controlled, open-label, parallel, multicenter trial enrolled prevalent patients on hemodialysis. The study endpoints were to establish the non-inferiority of expanded hemodialysis versus haemodiafiltration in removing beta-2-microglobulin (β2M) and lambda-free light chains (λFLC) and to evaluate the reduction ratios of urea, alpha-1-microglobulin (α1M), myoglobin, complement factor D, kappa-free light chains (κFLC) and Chitinase-3-like protein 1 (YKL-40) during a mid-week dialysis session. The 95% confidence intervals of the difference in λFLC and β2M reduction ratios with expanded hemodialysis were compared against pre-defined non-inferiority margins (-3.783 and -7.848, respectively). Non-inferior reduction ratios were tested for superiority using hierarchical testing.

RESULTS:

Overall, 274 adult patients were randomized to expanded hemodialysis (n = 138) or haemodiafiltration (n = 136). No differences in demographics, baseline characteristics, and treatment parameters were observed between the arms. The reduction ratio of λFLC with expanded hemodialysis was superior to haemodiafiltration; reduction ratio difference of 17.0% [95% confidence interval: 14.8%, 19.2%]. The reduction ratio of β2M with expanded hemodialysis was non-inferior to haemodiafiltration; reduction ratio difference of -1.2% [95% confidence interval: -2.5%, 0.2%]. Expanded hemodialysis showed significantly higher removal of α1M, YKL-40, complement factor D, myoglobin, and κFLC than haemodiafiltration therapy. There were no significant differences in Kt/Vurea, urea reduction ratio, and the rate of complications between the arms.

CONCLUSION:

Our study demonstrates the effectiveness of expanded hemodialysis therapy in removing multiple middle molecules compared to haemodiafiltration therapy, with no observed differences in the overall safety of Chinese patients.

2025-12-01·JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE

An economic model for different anticoagulation strategies in continuous renal replacement therapy

Article

作者: Ethgen, Olivier ; Harenski, Kai ; Tolwani, Ashita ; Echeverri, Jorge ; Zarbock, Alexander

PURPOSE:

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of regional citrate anticoagulation (RCA) or systemic heparin anticoagulation (SHA) during continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) in critically ill patients.

METHODS:

A decision-analytic model was developed to calculate an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio between RCA and SHA from a US healthcare payer perspective. Key differentiator was the risk of bleeding derived from the RCA and SHA groups in the RICH trial. Base case didn't consider the potential impact of bleeding on length of stay (LOS) or mortality. Three scenarios were considered: 1-impact of bleeding on LOS; 2-impact of bleeding on mortality; and 3-impact of bleeding on both LOS and mortality.

RESULTS:

Base case: RCA was associated with an incremental cost of +$577 compared with SHA. Scenario 1: RCA resulted in cost savings of -$311. Scenario 2: RCA incurred incremental costs of +$614 for +0.076 incremental QALYs (+$8131/QALY). Scenario 3: RCA appeared to be a dominant strategy over SHA. Sensitivity analyses showed the results were robust to parameter uncertainties.

CONCLUSION:

RCA is an economically attractive alternative to SHA, especially when bleeding leads to longer hospital stays. Observational research is warranted to document the impact of bleeding on LOS to confirm the economic value of RCA over SHA.

807

项与 Baxter International, Inc. 相关的新闻(医药)2025-08-25

TORONTO, Aug. 25, 2025 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Spectral Medical Inc. (“Spectral” or the “Company”) (TSX: EDT), a late-stage theranostic company advancing therapeutic options for sepsis and septic shock, today announced that it has received the US$3 million Tranche B advance from Vantive US Healthcare LLC (“Vantive”) pursuant to the previously disclosed senior secured promissory note entered into in May 2025. The Tranche B advance further strengthens Spectral’s balance sheet and will be used to support ongoing regulatory and commercialization preparations, as well as general working capital requirements. Spectral does not anticipate requiring any additional funding – beyond the fully drawn senior secured promissory note as previously disclosed – to meet its upcoming key milestones, including U.S. FDA submission, and through to PMX commercialization. “We appreciate Vantive’s continued support and are pleased to have closed the Tranche B advance,” said Chris Seto, Chief Executive Officer of Spectral Medical. “This non-dilutive capital enhances our liquidity and provides additional flexibility as we execute on our regulatory pathway and commercialization plans. With this funding in place, we remain focused on operational priorities.” Under the terms of the promissory note, Vantive may advance funds up to US$10 million to Spectral in up to four separate tranches to support Spectral’s continued evidence generation strategy and path to commercialization of Toraymyxin™ (“PMX”). With the US$3 million Tranche B advance, together with the initial US$4 million Tranche A advance, the current cumulative draw of the promissory note is US$7 million. A copy of the Agreement has been filed under Spectral’s profile on SEDAR+ at www.sedarplus.ca. About Spectral Spectral is a Phase 3 company seeking U.S. FDA approval for its unique product for the treatment of patients with septic shock, Toraymyxin™ (“PMX”). PMX is a therapeutic hemoperfusion device that removes endotoxin, which can cause sepsis, from the bloodstream and is guided by the Company’s FDA cleared Endotoxin Activity Assay (EAA™), the clinically available test for endotoxin in blood. PMX is approved for therapeutic use in Japan and Europe, licensed by Health Canada, and has been used safely and effectively with over 360,000 units sold worldwide to date. In March 2009, Spectral obtained the exclusive development and commercial rights in the U.S. for PMX, and in November 2010, signed an exclusive distribution agreement for this product in Canada. In July 2022, the U.S. FDA granted Breakthrough Device Designation for PMX for the treatment of endotoxic septic shock. Approximately 330,000 patients are diagnosed with septic shock in North America each year. The Tigris Trial is a confirmatory study of PMX in addition to standard care vs standard care alone and is designed as a 2:1 randomized trial of 150 patients using Bayesian statistics. Endotoxic septic shock is a malignant form of sepsis https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6RANrHHi9L8. The trial methods are detailed in “Bayesian methods: a potential path forward for sepsis trials”. Spectral is listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange under the symbol EDT. For more information, please visit www.spectraldx.com. Forward-looking statement Information in this news release that is not current or historical factual information may constitute forward-looking information within the meaning of securities laws. Implicit in this information, particularly in respect of the future outlook of Spectral and anticipated events or results, are assumptions based on beliefs of Spectral's senior management as well as information currently available to it. While these assumptions were considered reasonable by Spectral at the time of preparation, they may prove to be incorrect. Readers are cautioned that actual results are subject to a number of risks and uncertainties, including the availability of funds and resources to pursue R&D projects, the successful and timely completion of clinical studies, the ability of Spectral to take advantage of business opportunities in the biomedical industry, the granting of necessary approvals by regulatory authorities as well as general economic, market and business conditions, and could differ materially from what is currently expected. The TSX has not reviewed and does not accept responsibility for the adequacy or accuracy of this statement. For further information, please contact: Ali Mahdavi Chris SetoCapital Markets & Investor Relations CEOSpinnaker Capital Markets Inc. Spectral Medical Inc.416-962-3300 am@spinnakercmi.com cseto@spectraldx.com

引进/卖出临床3期上市批准

2025-08-19

The activist investor firm did not disclose the exact size of its recently acquired stake in the medtech giant, however sizable. \n Medtronic has agreed to not only expand the size of its board of directors, but to also task it with taking a closer look at cutting costs and exploring more tuck-in M&A—after what it described as a “constructive dialogue” with the company’s newest stakeholder, Elliott Investment Management.The activist investor firm did not disclose the exact size of its recently acquired stake in the medtech giant, however sizable, alongside the company’s second-quarter earnings report.“Our decision to become one of Medtronic\'s largest investors was driven by our strong conviction that the company is entering a new chapter of exceptional value creation defined by accelerating growth, operational improvement and enhanced strategic clarity,” Elliott Partner Marc Steinberg said in a statement. “We believe Medtronic\'s recent innovations in some of the medical technology sector\'s most attractive markets have positioned the company for an inflection in organic growth.”“Today\'s announcements—including the addition of new directors with deep medical technology experience and the formation of two focused Board committees—are the right steps towards realizing Medtronic\'s potential,” Steinberg added. The two new independent directors are John Groetelaars, former CEO of Hillrom and Dentsply Sirona, and Bill Jellison, previously a chief financial officer at Stryker, and who until this week was a board member at Masimo with a focus on M&A, after gaining his seat there in 2024 following a proxy fight with Politan Capital Management. Their new titles are effective immediately.The two new committees, meanwhile, will include teams focused on growth and operations. The former will consider possible acquisitions, R&D investments and divestitures—such as the currently planned departure of Medtronic’s $2.8 billion diabetes unit—while the latter will evaluate potential efficiencies and ways to simplify its global manufacturing and supply chain. Both will be chaired by Medtronic’s CEO, Geoff Martha. “I am pleased to welcome John and Bill to the Medtronic Board of Directors—each of whom brings decades of relevant experience delivering growth as executives and directors of public companies in the medical technology industry. John\'s leadership managing global operations and Bill\'s deep financial expertise will also be valuable to the boardroom,” Martha said.“We are at an exciting inflection point and in a period of strong momentum, with multiple growth drivers already delivering and additional breakthrough therapies set to launch in the months ahead,” he added. “The separation of MiniMed is an example of the important steps we\'re taking to create a more focused and more profitable Medtronic.”The company said it plans to host an investor day in mid-2026 to outline its strategic priorities and detail the work of the two board committees.\"We appreciate our productive dialogue with Marc Steinberg and the Elliott team,” Martha said. “The durable growth drivers now taking hold across several of our businesses are strengthening Medtronic\'s trajectory and reinforcing our conviction in the company\'s future. The Board believes Medtronic has the right strategies to build on this momentum and deliver sustained, superior returns for investors over the long term.” Medtronic has been looking to reshape itself over the past several years, including through the post-COVID exit of the hospital ventilator business. Before deciding to spin out its diabetes division—with its portfolio of insulin delivery systems and wearable blood sugar trackers—the company had previously planned to hive off its acute care and patient monitoring segments, though that plan was ultimately reversed. Medtronic also once pursued a $738 million buyout of the South Korean insulin patch-pump developer EOFlow, but the deal was scrapped after that company became snarled in a patent and trade secrets dispute with the Omnipod maker Insulet. For the second quarter of this year, Medtronic reported $8.58 billion in revenue for an 8.4% gain over the same period in 2024. The company’s cardiovascular portfolio brought in $3.28 billion, for a 9.3% gain, while neuroscience devices totaled $2.42 billion, up 4.3%. Medical surgical hardware added $2.08 billion in sales, growing 4.4%, while its diabetes business rose 11.5% to $721 million.“We delivered another consistent quarter of mid-single digit organic revenue growth, with broad strength from several innovative product categories, including Pulsed Field Ablation, Transcatheter Valves, Neuromodulation, Diabetes, and Leadless Pacing,\" Martha said.The company also raised some of its financial forecasts for the 2026 fiscal year, bumping its earnings-per-share growth to about 4.5%, up from its previous projection of 4%, to land between $5.60 and $5.66.That excludes the potential impact of tariffs, however, which Medtronic has now lowered to about $185 million compared to the prior range of $200 million to $350 million. The company did not make changes to its revenue guidance, which it had pegged at about 5%.“As a result of our Q1 EPS outperformance and improved tariff impact assumption, we are raising our full year EPS guidance,” said CFO Thierry Piéton. “Our confidence continues to increase as we advance our revenue growth drivers and execute on efficiencies in manufacturing, supply chain, and operating expenses to drive earnings growth, and increase our growth investments in R&D, sales, and marketing, all with a deliberate focus on creating long-term shareholder value.”Editor\'s note: In an August 19 filing with the SEC, Masimo disclosed that Bill Jellison had resigned from the company\'s board the day prior.

并购高管变更

2025-08-19

Experienced executives John Groetelaars and Bill Jellison appointed to the Board of Directors

Board forms new Growth and Operating committees to sharpen focus on the company's ongoing strategic portfolio management, operational execution and capital allocation

Plan to host Investor Day in 2026

Initiatives follow constructive engagement with Elliott Management

GALWAY, Ireland, Aug. 19, 2025 /PRNewswire/ -- Medtronic plc (NYSE: MDT), a global leader in healthcare technology, today announced the Medtronic Board of Directors has appointed John Groetelaars and Bill Jellison as independent directors, effective immediately.

Consistent with the company's commitment to shareholder value creation, and to provide enhanced focus and urgency around Medtronic's ongoing strategic portfolio management, operational improvement and capital allocation, the Board has formed the following special committees to align our governance with existing management focus areas and workstreams:

The Growth Committee will be responsible for guiding the evaluation and execution of growth-accretive tuck-in M&A, organic R&D investments, and potential divestitures, including the continued execution of the recently announced plan to separate its Diabetes business.

The Operating Committee will align governance with the company's initiatives to optimize operational performance, deliver margin expansion, and drive sustained earnings acceleration, including actions company management is taking to improve efficiency in its global manufacturing, supply chain, and operations.

Chief Executive Officer and Chairman of the Board, Geoff Martha, will serve as Chair of both of the newly formed committees, and newly appointed directors, Groetelaars and Jellison, will also serve on one or both of the committees.

"I am pleased to welcome John and Bill to the Medtronic Board of Directors – each of whom brings decades of relevant experience delivering growth as executives and directors of public companies in the medical technology industry. John's leadership managing global operations and Bill's deep financial expertise will also be valuable to the boardroom," said Geoff Martha, chairman and chief executive officer. "We are at an exciting inflection point and in a period of strong momentum, with multiple growth drivers already delivering and additional breakthrough therapies set to launch in the months ahead. With the addition of these new Board members and the formation of these two new committees, we are accelerating our strategic growth priorities and advancing the simplification and optimization of our operations. The separation of MiniMed is an example of the important steps we're taking to create a more focused and more profitable Medtronic. By sharpening our focus on high-margin growth opportunities, we are well-positioned to deliver stronger performance and greater value for patients, customers, and shareholders."

Medtronic will host an Investor Day in mid-calendar year 2026 at which the company will discuss the work of the Growth Committee and Operating Committee, including Medtronic's go-forward strategic priorities and financial algorithm.

Today's initiatives follow constructive dialogue with Elliott Investment Management L.P. ("Elliott").

Martha continued, "We appreciate our productive dialogue with Marc Steinberg and the Elliott team. The durable growth drivers now taking hold across several of our businesses are strengthening Medtronic's trajectory and reinforcing our conviction in the company's future. The Board believes Medtronic has the right strategies to build on this momentum and deliver sustained, superior returns for investors over the long-term."

Elliott Partner Marc Steinberg said, "Our decision to become one of Medtronic's largest investors was driven by our strong conviction that the company is entering a new chapter of exceptional value creation defined by accelerating growth, operational improvement and enhanced strategic clarity. We believe Medtronic's recent innovations in some of the medical technology sector's most attractive markets have positioned the company for an inflection in organic growth. Combined with its renewed focus on portfolio simplification and improved operational execution, Medtronic is set to deliver a sustainable acceleration in earnings growth as well. Today's announcements – including the addition of new directors with deep medical technology experience and the formation of two focused Board committees – are the right steps towards realizing Medtronic's potential. We look forward to continuing our constructive partnership with Geoff Martha and the Board and to working closely together to realize this unique value-creation opportunity."

Groetelaars and Jellison will be nominated to stand for election to the Board at Medtronic's 2025 Annual General Meeting of Shareholders.

New Board Member Biographies

John Groetelaars brings more than 30 years of global leadership experience across a broad range of medical device sectors. Most recently, Groetelaars served as interim CEO for Dentsply Sirona, having previously served in a director role for the company. Prior to Dentsply Sirona, John was President & CEO at Hillrom from May 2018 until the company's acquisition by Baxter International, Inc. in 2021. At Hillrom, he provided global leadership for a healthcare technology company with $3 billion in revenue and 10,000+ employees. Prior to joining Hillrom, Groetelaars served as executive vice president and president of the Interventional Segment at Becton, Dickinson and Company following its acquisition of C.R. Bard in December 2017.

Currently, Groetelaars serves as Chairman of the Board of Directors for Zeus Industrial Products. He is also a Board member for Parexel, a global clinical research organization.

Groetelaars earned a bachelor's degree in Mechanical Engineering from Kettering University and an MBA from Columbia University.

William Jellison is a former medical technology executive and corporate finance expert. From 2013 to 2016, he served as the Vice President, Chief Financial Officer of Stryker Corporation, a global leader in medical technologies. Before joining Stryker, Jellison spent 15 years at Dentsply International in several leadership positions, including CFO. Jellison began his career with the Donnelly Corporation, holding multiple financial management and executive roles, including Vice President of Finance, Treasurer and Corporate Controller.

Jellison currently serves as a Senior Advisor for Astor Place Holdings, the Private Equity arm of Select Equities, and consults with other companies in the medical technology industry. He serves as a director of public companies Avient Corporation and Anika Therapeutics, Inc. as well as a director of private companies Solenis and Young Innovations.

Jellison received a B.A. in Business Administration from Hope College.

About Medtronic

Bold thinking. Bolder actions. We are Medtronic. Medtronic plc, headquartered in Galway, Ireland, is the leading global healthcare technology company that boldly attacks the most challenging health problems facing humanity by searching out and finding solutions. Our Mission — to alleviate pain, restore health, and extend life — unites a global team of 95,000+ passionate people across more than 150 countries. Our technologies and therapies treat 70 health conditions and include cardiac devices, surgical robotics, insulin pumps, surgical tools, patient monitoring systems, and more. Powered by our diverse knowledge, insatiable curiosity, and desire to help all those who need it, we deliver innovative technologies that transform the lives of two people every second, every hour, every day. Expect more from us as we empower insight-driven care, experiences that put people first, and better outcomes for our world. In everything we do, we are engineering the extraordinary. For more information on Medtronic (NYSE: MDT), visit and follow Medtronic on LinkedIn.

Any forward-looking statements are subject to risks and uncertainties such as those described in Medtronic's periodic reports on file with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Actual results may differ materially from anticipated results.

Contacts:

Erika Winkels

Public Relations

+1-763-526-8478

Ryan Weispfenning

Investor Relations

+1-763-505-4626

SOURCE Medtronic plc

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

高管变更并购

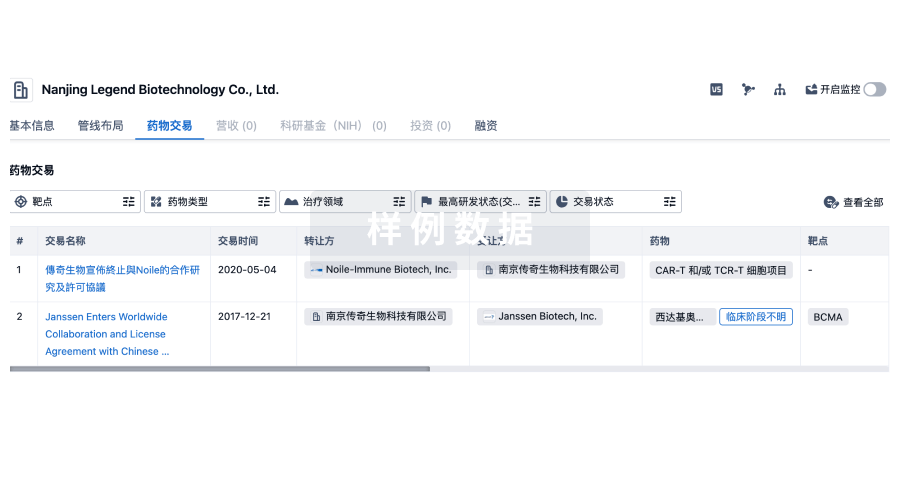

100 项与 Baxter International, Inc. 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

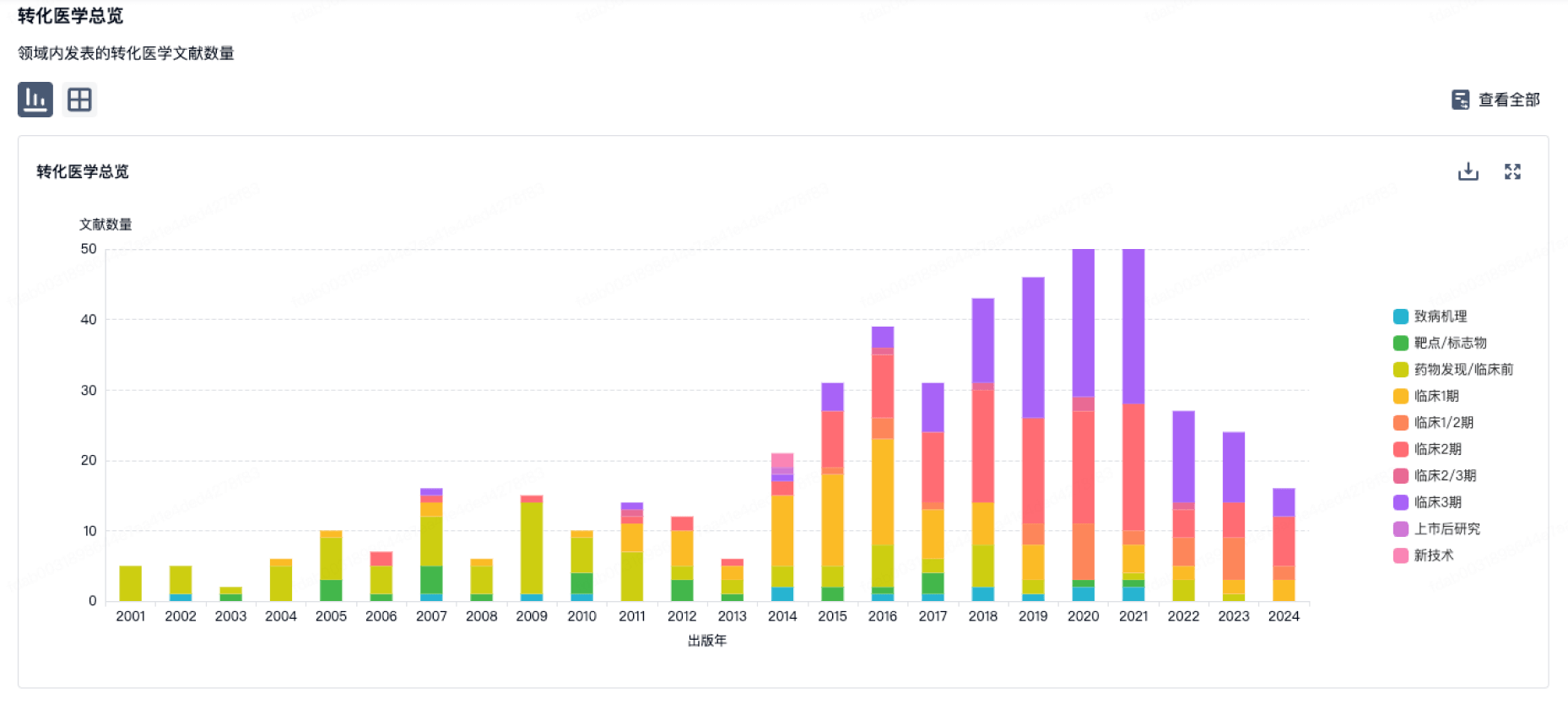

100 项与 Baxter International, Inc. 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

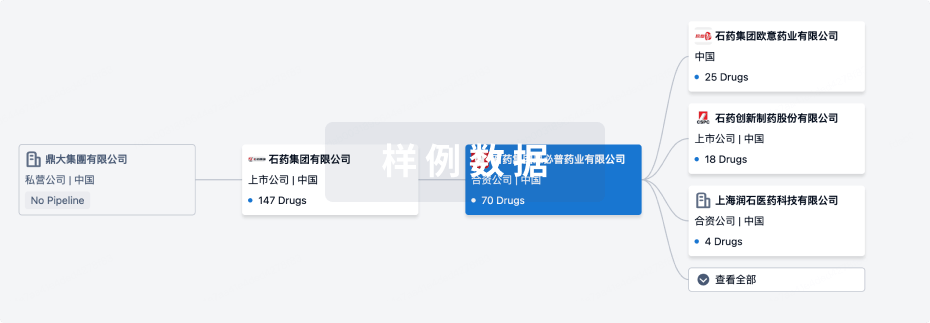

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2025年11月04日管线快照

管线布局中药物为当前组织机构及其子机构作为药物机构进行统计,早期临床1期并入临床1期,临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

临床前

3

1

临床2期

临床3期

4

2

申请上市

批准上市

72

66

其他

登录后查看更多信息

当前项目

| 药物(靶点) | 适应症 | 全球最高研发状态 |

|---|---|---|

环磷酰胺 ( DNA ) | 卵巢腺癌 更多 | 批准上市 |

依普利酮 ( MR ) | 左心室功能不全 更多 | 批准上市 |

培美曲塞二钠 ( DHFR x GART x TYMS ) | 转移性非小细胞肺癌 更多 | 批准上市 |

盐酸多柔比星脂质体 ( Top II ) | 艾滋病相关性卡波西肉瘤 更多 | 批准上市 |

重组人凝血因子Ⅷ(Takeda) ( F10 ) | 血友病A 更多 | 批准上市 |

登录后查看更多信息

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

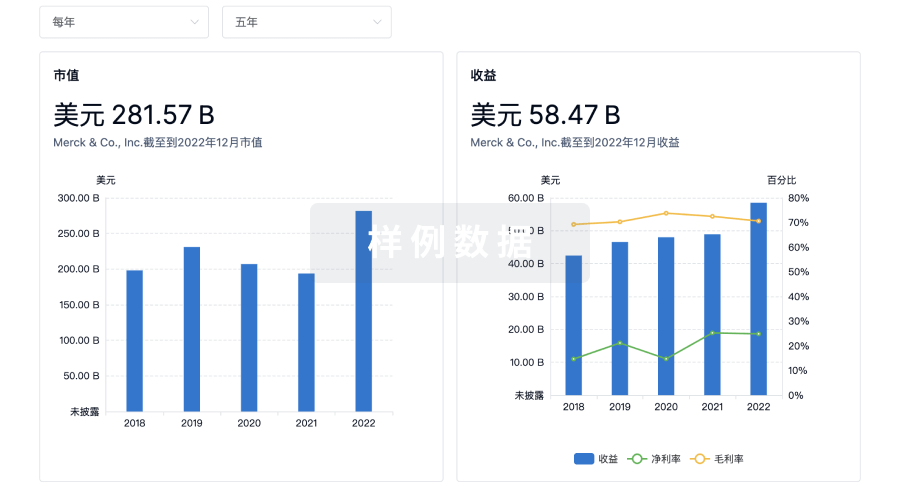

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用