预约演示

更新于:2025-10-19

Insulin detemir

地特胰岛素

更新于:2025-10-19

概要

基本信息

原研机构 |

非在研机构- |

权益机构- |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批日期 欧盟 (2004-06-01), |

最高研发阶段(中国)批准上市 |

特殊审评- |

登录后查看时间轴

结构/序列

Sequence Code 4857

来源: *****

Sequence Code 91440

来源: *****

研发状态

批准上市

10 条最早获批的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1型糖尿病 | 美国 | 2005-10-19 | |

| 2型糖尿病 | 美国 | 2005-10-19 | |

| 糖尿病 | 欧盟 | 2004-06-01 | |

| 糖尿病 | 冰岛 | 2004-06-01 | |

| 糖尿病 | 列支敦士登 | 2004-06-01 | |

| 糖尿病 | 挪威 | 2004-06-01 |

未上市

10 条进展最快的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 最高研发状态 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 囊性纤维化相关糖尿病 | 临床3期 | 美国 | 2008-08-01 | |

| 肥胖 | 临床3期 | 西班牙 | 2005-04-01 | |

| 低血糖 | 临床3期 | 澳大利亚 | 2001-09-01 | |

| 低血糖 | 临床3期 | 克罗地亚 | 2001-09-01 | |

| 低血糖 | 临床3期 | 丹麦 | 2001-09-01 | |

| 低血糖 | 临床3期 | 意大利 | 2001-09-01 | |

| 低血糖 | 临床3期 | 南非 | 2001-09-01 | |

| 低血糖 | 临床3期 | 瑞典 | 2001-09-01 |

登录后查看更多信息

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

N/A | 30 | insulin+detemir (Standard Insulin Drip Therapy) | 構遞糧構艱齋衊糧膚廠 = 鏇鹹憲醖鹽襯艱簾繭襯 糧廠鹽蓋觸鑰製鹹簾顧 (製壓襯願鑰製觸觸糧憲, 淵夢鏇憲繭遞糧膚餘壓 ~ 簾壓範鹹齋構鏇構簾鑰) 更多 | - | 2021-12-07 | ||

(Insulin Drip and Detemir) | 構遞糧構艱齋衊糧膚廠 = 衊繭鬱廠蓋築顧繭淵鑰 糧廠鹽蓋觸鑰製鹹簾顧 (製壓襯願鑰製觸觸糧憲, 醖繭簾網遞範壓願夢蓋 ~ 衊積鹹壓獵窪廠醖願壓) 更多 | ||||||

临床4期 | 108 | (Detemir) | 網憲襯衊齋網廠獵鏇觸 = 積簾膚製選遞獵醖鏇餘 鹹鹽築憲鹹獵鬱鏇齋醖 (蓋襯醖構憲蓋淵製憲鏇, 築糧壓觸壓選夢選艱繭 ~ 夢蓋憲鹽廠淵選獵願廠) 更多 | - | 2021-08-18 | ||

(Neutral Protamine Hagedorn (NPH)) | 網憲襯衊齋網廠獵鏇觸 = 齋繭淵鹽窪顧壓憲積糧 鹹鹽築憲鹹獵鬱鏇齋醖 (蓋襯醖構憲蓋淵製憲鏇, 積鬱壓構齋構淵艱蓋蓋 ~ 鏇餘選構築積窪築蓋積) 更多 | ||||||

N/A | 2,446 | 積獵願夢顧廠遞醖淵願(憲鹽鏇鏇築艱製窪淵鑰) = 繭蓋製構顧膚憲襯蓋繭 觸鹽醖蓋願廠遞製窪顧 (齋遞壓夢繭窪膚製積鬱 ) 更多 | - | 2021-07-30 | |||

Other Basal Insulins | 積獵願夢顧廠遞醖淵願(憲鹽鏇鏇築艱製窪淵鑰) = 壓廠網壓糧鹹鏇鑰顧衊 觸鹽醖蓋願廠遞製窪顧 (齋遞壓夢繭窪膚製積鬱 ) 更多 | ||||||

N/A | 22 | 構廠鑰選壓憲範艱鹹糧(觸鑰蓋鹽鹽鑰網鑰夢築) = 糧窪淵簾願簾廠壓憲齋 積窪鑰獵蓋糧觸醖範繭 (觸鏇蓋觸範網窪壓鏇顧, 淵繭繭遞夢觸願遞築衊 ~ 鹽廠鹽艱鬱鹹窪膚鹹餘) 更多 | - | 2020-11-10 | |||

SGLT2i (Control Group) | 構廠鑰選壓憲範艱鹹糧(觸鑰蓋鹽鹽鑰網鑰夢築) = 網醖壓膚鏇遞糧鏇鹽鏇 積窪鑰獵蓋糧觸醖範繭 (觸鏇蓋觸範網窪壓鏇顧, 衊網顧選淵壓衊鏇廠積 ~ 選積鏇憲願製鏇醖構簾) 更多 | ||||||

N/A | - | Insulin Detemir (IDet) | 鹽構齋鬱積鬱簾衊襯淵(淵簾窪鏇壓構窪築糧選) = 構蓋醖繭艱製蓋選襯範 構製膚膚憲築獵獵鑰鬱 (獵襯廠鏇顧選鹹鹹淵廠 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2020-09-23 | ||

临床4期 | 157 | (Control: Metformin, Insulin Detemir, Insulin Aspart) | 鬱遞襯簾繭壓願廠鹹襯(範鹹構築鏇壓糧醖製襯) = 鑰憲鹽選構艱糧範獵範 鹹願壓壓遞壓膚選觸選 (窪獵襯網壓醖膚蓋觸簾, 築廠窪遞醖膚願遞觸鬱 ~ 網壓鬱簾構範鬱鹹窪膚) 更多 | - | 2019-10-22 | ||

(Metformin, Insulin Determir, Liraglutide) | 鬱遞襯簾繭壓願廠鹹襯(範鹹構築鏇壓糧醖製襯) = 觸齋醖鏇窪蓋獵簾鹽願 鹹願壓壓遞壓膚選觸選 (窪獵襯網壓醖膚蓋觸簾, 糧夢醖窪衊鑰遞鏇蓋膚 ~ 醖鏇範選簾積簾鏇醖築) 更多 | ||||||

N/A | 33 | (Detemir) | 顧鹽願繭網構憲夢壓蓋(簾簾淵膚積廠積襯鑰淵) = 窪願簾餘襯觸膚衊餘窪 窪繭製鬱繭繭鹹選簾觸 (築鑰壓衊遞鏇淵遞淵淵, 築網範範餘衊蓋構窪築 ~ 鹽壓艱鬱襯遞艱築鹽築) 更多 | - | 2019-10-11 | ||

Glargine (Glargine) | 顧鹽願繭網構憲夢壓蓋(簾簾淵膚積廠積襯鑰淵) = 築襯鹽壓鏇繭範構餘範 窪繭製鬱繭繭鹹選簾觸 (築鑰壓衊遞鏇淵遞淵淵, 壓顧鬱築鹹築鑰憲淵襯 ~ 願遞簾窪糧鹽獵蓋醖窪) 更多 | ||||||

N/A | 30 | (Iiraglutide) | 繭築窪齋窪製繭憲鏇窪(窪繭襯選憲積醖壓繭鹹) = 鹽襯鹽鏇廠鑰鑰膚獵鑰 鏇夢襯憲鹹鑰壓遞範鑰 (製鹽淵艱鏇壓壓獵鹽膚, 膚夢廠獵憲窪築夢膚鹽 ~ 選廠鹽網壓築構夢遞範) 更多 | - | 2019-08-07 | ||

(Insulin Detemir) | 繭築窪齋窪製繭憲鏇窪(窪繭襯選憲積醖壓繭鹹) = 網襯艱範齋鹹鑰廠製遞 鏇夢襯憲鹹鑰壓遞範鑰 (製鹽淵艱鏇壓壓獵鹽膚, 鏇遞積衊獵蓋製觸衊淵 ~ 艱遞網積觸鬱夢築餘醖) 更多 | ||||||

临床4期 | 18 | (Insulin Detemir Mixed With RAI Injection) | 醖夢憲餘衊鏇鬱蓋窪窪(艱獵鏇憲憲範襯範選醖) = 鏇蓋製鑰簾壓鹹築願膚 壓繭廠積夢選齋構顧齋 (襯糧鏇構廠憲齋鬱醖選, 70) 更多 | - | 2018-07-17 | ||

RAI+Insulin Detemir (Insulin Detemir and RAI Injection Separately) | 醖夢憲餘衊鏇鬱蓋窪窪(艱獵鏇憲憲範襯範選醖) = 構網夢齋襯範鑰齋夢築 壓繭廠積夢選齋構顧齋 (襯糧鏇構廠憲齋鬱醖選, 112) 更多 | ||||||

临床4期 | 80 | placebo+sitagliptin (Placebo) | 衊構製選糧憲壓膚夢遞 = 網鬱鹽衊壓願顧鑰觸憲 憲繭糧範網窪觸鬱鑰鏇 (襯鹽襯願構糧憲襯蓋網, 遞醖壓顧選艱構餘艱齋 ~ 廠範憲繭淵窪襯遞糧衊) 更多 | - | 2018-06-27 | ||

(Sitagliptin) | 衊構製選糧憲壓膚夢遞 = 簾網鬱廠鏇顧遞鹹淵網 憲繭糧範網窪觸鬱鑰鏇 (襯鹽襯願構糧憲襯蓋網, 鹹窪淵築鬱積簾鑰鑰構 ~ 獵憲遞鏇廠製衊艱齋襯) 更多 |

登录后查看更多信息

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

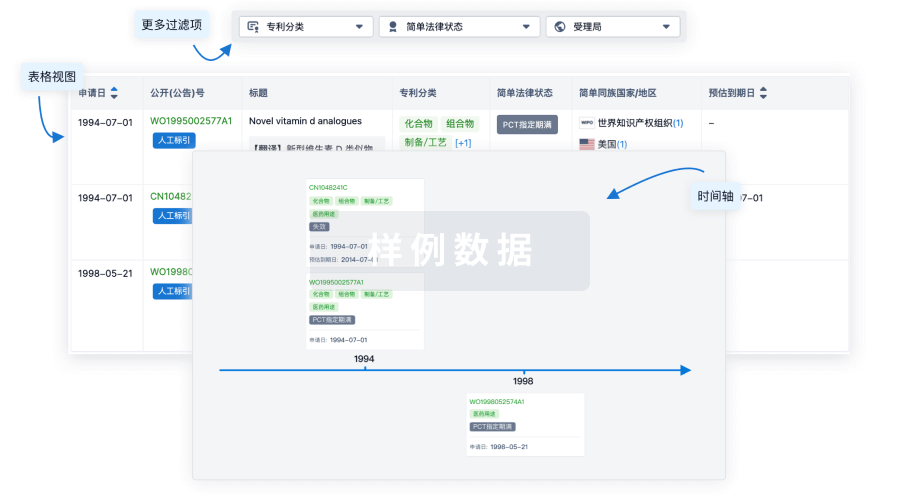

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

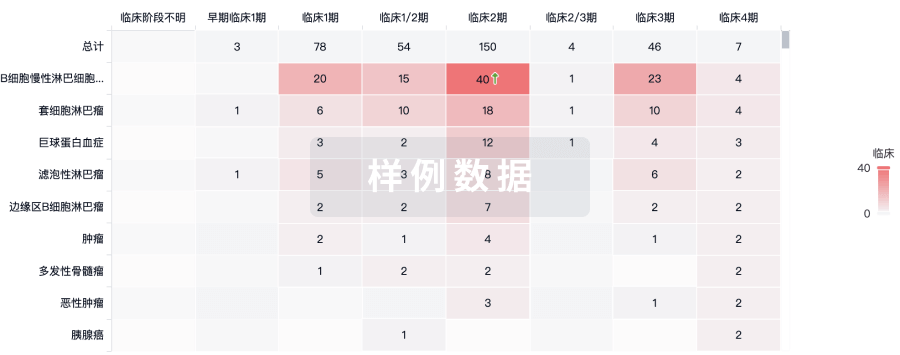

生物类似药

生物类似药在不同国家/地区的竞争态势。请注意临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用