预约演示

更新于:2025-10-13

Beijing GeneCradle Technology Co., Ltd.

更新于:2025-10-13

概览

标签

其他疾病

神经系统疾病

遗传病与畸形

腺相关病毒基因治疗

转运RNA

基因疗法

疾病领域得分

一眼洞穿机构专注的疾病领域

暂无数据

技术平台

公司药物应用最多的技术

暂无数据

靶点

公司最常开发的靶点

暂无数据

| 排名前五的药物类型 | 数量 |

|---|---|

| 腺相关病毒基因治疗 | 7 |

| 转运RNA | 1 |

| 基因疗法 | 1 |

关联

9

项与 北京锦篮基因科技股份有限公司 相关的药物靶点 |

作用机制 SMN1基因刺激剂 |

在研机构 |

原研机构 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床3期 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

作用机制 GAA基因转移 |

在研机构 |

原研机构 |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床1/2期 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

靶点 |

作用机制 ATP7B基因刺激剂 |

在研机构 |

原研机构 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床1/2期 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

11

项与 北京锦篮基因科技股份有限公司 相关的临床试验NCT07173933

A Multicenter, Open-label, Single-dose, Dose-escalation Phase I/II Clinical Trial Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of GC310 Adeno-associated Virus Injection in the Treatment of Patients With Wilson's Disease (WD)

The goal of this clinical trial is to learn if GC310 (AAV5-ATP7B) gene therapy can treat Wilson's Disease (WD) in patients over the age of 18 years old. The main questions it aims to answer are:

Is GC310 safe and tolerable to WD patients? What is the recommended phase II dose (RP2D)? What is the change from baseline in 24-hour urinary copper concentration after 52 weeks of administration?

Participants will be administrated GC310 intravenously and be followed up for 52 weeks to observe drug safety, tolerability and efficacy .

Is GC310 safe and tolerable to WD patients? What is the recommended phase II dose (RP2D)? What is the change from baseline in 24-hour urinary copper concentration after 52 weeks of administration?

Participants will be administrated GC310 intravenously and be followed up for 52 weeks to observe drug safety, tolerability and efficacy .

开始日期2025-10-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06971094

A Multicenter, Randomized, Open-Label, Standard-of-Care-Controlled, Phase III Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Intrathecal (IT) Injection of GC101 Adeno-Associated Virus Injection in the Treatment of Patients With Type 2 Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA)

This trial employs a multicenter, randomized, open-label, standard-of-care-controlled design and plans to enroll 50 patients with Type 2 SMA aged 2 to 12 years who have previously received nusinersen. The primary objective of the trial is to evaluate the efficacy of GC101 in treating Type 2 SMA. The secondary objectives are to assess the efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of GC101 in treating Type 2 SMA.

开始日期2025-05-27 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT05860569

A Multi-center, Open Label, Multi-arm, Dose Ascending Clinical Trial for Evaluation of Safety and Tolerance of Gene Therapy Drug GC304 in the Treatment of Primary Hypertriglyceridemia Patients With History of Acute Pancreatitis

The study will evaluate safety and tolerance of intravenous delivery of GC304 gene therapy drug as a treatment of primary hypertriglyceridemic patients with previous onset of acute pancreatitis.

开始日期2024-09-20 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 北京锦篮基因科技股份有限公司 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 北京锦篮基因科技股份有限公司 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

3

项与 北京锦篮基因科技股份有限公司 相关的文献(医药)2025-12-01·JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICAL AND BIOMEDICAL ANALYSIS

Microflow LC-MS/MS reveals platform-specific post-translational modification signatures in recombinant adeno-associated virus capsids linked to enhanced potency and stability: A quality control framework for gene therapy

Article

作者: Dai, Yangguang ; Ma, Qiang ; Zhou, Yong ; Wang, Wentao ; Jin, Jing ; Chen, Hongxu ; Wang, Lijun ; Gao, Tie ; Li, Xiu ; Tao, Lei

Recombinant adeno-associated viruses (rAAVs) are pivotal gene therapy vectors due to their safety and stable transduction, yet comprehensive characterization of capsid post-translational modifications (PTMs)-critical for potency, immunogenicity, and manufacturing consistency-remains limited across production platforms. This study employs microflow LC-MS/MS coupled with electron-activated dissociation (EAD) to analyze PTMs in clinically relevant rAAV5 and rAAV9 serotypes produced via mammalian (HEK293) and insect (Sf9) cells, with parallel cellular-level evaluation of vector potency and infectivity, conducted under matched purity and capsid thermal stability conditions to isolate PTM-specific effects. Intact mass analysis revealed conserved N-terminal acetylation in VP1/VP3 across both platforms, while PTM profiling identified six distinct modification types, including deamidation, oxidation, and phosphorylation, with Sf9-derived vectors exhibiting 14 % more PTMs than HEK293-produced counterparts. Despite comparable purity and thermostability, HEK293-derived vectors demonstrated superior in vitro potency (1.9-fold higher eGFP expression) and lower physical-to-infectious particle ratios (P:I, 1.8-3.2-fold reduction), linking PTM patterns to enhanced infectivity. EAD fragmentation mapped isoaspartate (IsoAsp) formation to specific asparagine residues, implicating deamidation-driven instability, while analysis of four Sf9-produced rAAV9 batches revealed ≤ 5 % lot-to-lot variability in PTM site counts. Preliminary data identified low-variance PTM sites (e.g., N57, N452; coefficient of variation, CV ≤ 15 %) and IsoAsp levels (CV ≤ 10 %) as potential stability markers for batch consistency monitoring, though their definitive utility as critical quality attributes requires further validation. These findings establish serotype- and platform-specific PTM landscapes under controlled biophysical parameters, providing actionable insights for optimizing production systems and establishing PTM-driven quality control in gene therapy.

Viruses-Basel

Methodological Validation and Inter-Laboratory Comparison of Microneutralization Assay for Detecting Anti-AAV9 Neutralizing Antibody in Human

Article

作者: Han, Xiaohong ; Fu, Diyi ; Zhai, Xiaoliang ; Ma, Wenhao ; Dong, Xiaoyan ; Jiang, Lijie ; Dong, Zheyue ; Zhou, Jianfang ; Zhang, Cengceng ; Zhu, Xueyang ; Yu, Shuangqing ; Zhao, Qian ; Zhang, Shuyang ; Wu, Xiaobing

Anti-AAV neutralizing Abs (NAbs) titer is usually measured by cell-based microneutralization (MN) assay and is crucial for patient screening in AAV-based gene therapy clinical trials. However, achieving uniform operation and comparable results among different laboratories remains challenging. Here, we established a standardized MN assay for anti-AAV9 NAbs in human sera or plasma and transferred the method to the other two research teams. Then, we validated its parameters and tested a set of eight human samples in blind across all laboratories. The end-point titer, defined by a transduction inhibition of 50% (IC50), was calculated using curve-fit modelling. A mouse neutralizing monoclonal antibody in human negative serum was used for system quality control (QC), requiring inter-assay titer variation of <4-fold difference or geometric coefficient of variation (%GCV) of <50%. The assay demonstrated a sensitivity of 54 ng/mL and no cross-reactivity to 20 μg/mL anti-AAV8 MoAb. The intra-assay and inter-assay variation for the low positive QC were 7–35% and 22–41%, respectively. The titers of the blind samples showed excellent reproducibility within and among laboratories, with a %GCV of 18–59% and 23–46%, respectively. This study provides a commonly transferrable MN assay for evaluating anti-AAV9 NAbs in humans, supporting its application in clinical trials.

Viruses

Using an In Vivo Mouse Model to Determine the Exclusion Criteria of Preexisting Anti-AAV9 Neutralizing Antibody Titer of Pompe Disease Patients in Clinical Trials

Article

作者: Yu, Shuangqing ; Liu, Ziyang ; Zheng, Xuchu ; Zhou, Jianfang ; Zhang, Cengceng ; Dong, Zheyue ; Wang, Hanqing ; Zhu, Xueyang ; Dong, Xiaoyan ; Wu, Xiaobing

The efficacy of adeno-associated virus (AAV)-based gene therapy is dependent on effective viral transduction, which might be inhibited by preexisting immunity to AAV acquired from infection or maternal delivery. Anti-AAV neutralizing Abs (NAbs) titer is usually measured by in vitro assay and used for patient enroll; however, this assay could not evaluate NAbs’ impacts on AAV pharmacology and potential harm in vivo. Here, we infused a mouse anti-AAV9 monoclonal antibody into Balb/C mice 2 h before receiving 1.2 × 1014 or 3 × 1013 vg/kg of rAAV9-coGAA by tail vein, a drug for our ongoing clinical trials for Pompe disease. The pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and cellular responses combined with in vitro NAb assay validated the different impacts of preexisting NAbs at different levels in vivo. Sustained GAA expression in the heart, liver, diaphragm, and quadriceps were observed. The presence of high-level NAb, a titer about 1:1000, accelerated vector clearance in blood and completely blocked transduction. The AAV-specific T cell responses tended to increase when the titer of NAb exceeded 1:200. A low-level NAbs, near 1:100, had no effect on transduction in the heart and liver as well as cellular responses, but decreased transduction in muscles slightly. Therefore, we propose to preclude patients with NAb titers > 1:100 from rAAV9-coGAA clinical trials.

105

项与 北京锦篮基因科技股份有限公司 相关的新闻(医药)2025-10-09

When Nirnay Murthy learned about a treatment for his toddler son’s rare condition, relief quickly gave way to disappointment.

A one-time gene therapy called Zolgensma from the Swiss drugmaker Novartis can halt spinal muscular atrophy, a deadly condition that causes muscles to waste away. But the medicine also carries a price tag of $2.1 million.

That sum felt almost unimaginable to Murthy, a veterinarian in India, where insurance does not cover Zolgensma. Still, Murthy tried. Last year, he crowdfunded $125,000, but it wasn’t nearly enough.

“It just shatters you inside. It makes you feel inadequate,” Murthy said.

Instead, Murthy used the money on a little-known alternative: an experimental gene therapy from a Chinese company called Lantu Biopharma. In May, a doctor dosed his 3-year-old son, Aryan, with the treatment.

Hello, Jaclyn Savage!

You’re an essential part of the biopharma world. Share your voice on this subscriber

Pulse Survey

to help shape our understanding of the industry.

Results will be anonymous.

Hello, Jaclyn Savage!

You’re an essential part of the biopharma world. Share your voice on this subscriber

Pulse Survey

to help shape our understanding of the industry.

Results will be anonymous.

Hello, Jaclyn Savage!

You’re an essential part of the biopharma world. Share your voice on this subscriber

Pulse Survey

to help shape our understanding of the industry.

Results will be anonymous.

Hello, Jaclyn Savage!

You’re an essential part of the biopharma world. Share your voice on this subscriber

Pulse Survey

to help shape our understanding of the industry.

Results will be anonymous.

Hello, Jaclyn Savage!

You’re an essential part of the biopharma world. Share your voice on this subscriber

Pulse Survey

to help shape our understanding of the industry.

Results will be anonymous.

Hello, Jaclyn Savage!

You’re an essential part of the biopharma world. Share your voice on this subscriber

Pulse Survey

to help shape our understanding of the industry.

Results will be anonymous.

Hello, Jaclyn Savage!

You’re an essential part of the biopharma world. Share your voice on this subscriber

Pulse Survey

to help shape our understanding of the industry.

Results will be anonymous.

Hello, Jaclyn Savage.

You’re an essential part of the biopharma world. Share your voice on this subscriber

Pulse Survey

to help shape our understanding of the industry.

Results will be anonymous.

Zolgensma is a miracle of modern medicine, but its steep price has largely placed it out of reach in poorer countries. Now, four Chinese companies are developing competing therapies, with plans to be much less expensive.

The trend is another example of

China’s fast-rising biotech scene

. But more than that, it’s a test of whether drugmakers there can deliver their advanced therapies to millions of people outside the richest countries in the world — and maybe, over time, those wealthier ones as well.

Murthy’s son received Lantu’s therapy through an early-access program while the treatment undergoes clinical trials.

“We will show the world that there is a better, more responsible, and economically more sensible way of drug development,” Lantu CEO Austin Gao said in an email.

In a statement, Novartis said Zolgensma is approved in 60 countries and that the company is “working to overcome any access challenges.” More than 5,000 patients across the globe have been treated, but the company declined to provide a breakdown of their nationalities.

Families affected by spinal muscular atrophy are yearning for a company — any company — to make a more obtainable gene therapy.

“What’s the point of a life-saving medication if it can only be accessed by a select few?” Murthy asked.

Spinal muscular atrophy is the

leading genetic cause of infant death

. In wealthier countries, change is afoot.

In the US, the condition is now screened for at birth in all 50 states. In 2023, some

70% of patients

had received one of the three treatments on the market, according to the nonprofit Cure SMA.

Novartis has justified Zolgensma’s multimillion-dollar price tag by arguing it’s the only curative, one-time therapy for the disease, and it replaces a lifetime of chronic, expensive care. The company has also highlighted research and development expenses, though critics say the cost is disproportionately high and doesn’t reflect

public investment

in the science behind the therapy.

Either way, payers in countries like the US, Australia and Japan, while balking at the price of Zolgensma, have negotiated coverage or reimbursement schemes that have made the medicine available to some families.

But the Murthy family represents a far different reality for much of the rest of the world.

It’s estimated that

one in 10,000 babies

in India is born with spinal muscular atrophy. When Aryan was born, he wasn’t tested for the condition.

It took until he was a toddler for symptoms to emerge: He could sit independently, had good neck control and could take a few supported steps, but he struggled to progress beyond that.

Last year, Aryan was diagnosed with the second most severe form of the disease, known as Type 2. If nothing was done, the deadly trajectory was clear: Aryan would struggle to move his limbs, to swallow and eventually to breathe.

While India is a manufacturing hub for medicines, families often can’t afford essential treatments in a

fragmented health landscape

.

The Murthy family has private insurance, which didn’t cover Zolgensma — a dynamic that may not change anytime soon, despite a recent milestone.

India’s top drug regulator approved Zolgensma in August, which will end the costly process of importing the drug. But it still may only be available to the wealthiest families.

A spokesperson for Novartis said the company hasn’t announced a price, but that the company is now in conversation with payers. It will be an uphill battle. Among private and public Indian payers, expensive rare disease treatments are typically considered a lower priority.

“Unless Novartis offers a significantly lower price — or other companies enter the market with more affordably priced options — I do not see a likely future where most patients will be able to access the drug,” said Melissa Barber, an expert on drug pricing in worldwide markets and postdoctoral fellow at the Yale School of Medicine.

In addition, families afflicted by spinal muscular atrophy were dismayed when, late last year, Novartis cited “the treatment landscape progressing”

in ending a worldwide lottery program

that provided Zolgensma for free to a limited number of patients.

While holding out hope for Zolgensma, Murthy paid about $54,000 for a yearly supply of Risdiplam, a Roche drug that increases the production of a key protein that those with SMA are deficient in, due to a genetic mutation. The daily medication improved his son’s symptoms.

Long-term, Murthy doubted whether he could continue to afford it. Zolgensma beckoned as not just a one-time solution, but clinical data suggested that it would prove superior in blunting Aryan’s disease. After Murthy’s crowdfunding campaign came up well short, he shared his plight with friends who are doctors, who connected him to Lantu Biopharma.

While it would be accessible, he had to weigh whether his son should be infused with a relatively unproven therapy, from a relatively unknown company.

Lantu was founded in 2020 in Guangzhou, China, to develop “lifesaving drugs for everyone in every corner of the world that needs them,” said Gao, the CEO. He declined to provide information on the company’s fundraising and its number of employees.

Lantu has been assisted by Bruce Lahn, a prominent geneticist and the chief scientific officer of VectorBuilder, a Chicago company that specializes in designing and manufacturing gene therapy vectors. Lahn declined to comment.

Murthy was comforted by his conversations with the company and early data.

“Only once we were 100% sure that it’s genuine, we went ahead,” Murthy said.

Lantu’s therapy, called Vesemnogene lantuparvovec, works in a similar way to Zolgensma. It uses a harmless virus, called AAV9, as a delivery vehicle to carry a healthy copy of the SMN1 gene into cells. Once inside, the gene helps the cells make the SMN1 protein that children with SMA lack.

In theory, it would be possible to make a copycat version of Zolgensma. While Vesemnogene lantuparvovec and Zolgensma appear similar, Lantu insisted its therapy is distinctive.

“Our team has devoted considerable time to understanding spinal-muscular atrophy and devising improved gene therapy approaches specifically for this condition. As a result, our therapy incorporates numerous distinctive design features,” Gao said.

Lantu is testing Vesemnogene lantuparvovec in gene therapy trials in China. Outside the country, the company has an early-access program, provided that families cover manufacturing costs that run about $125,000, according to interviews with Murthy and other parents.

The money that Murthy crowdfunded was just enough to participate. Gao said the program is run by local partners through technology transfer agreements, in the hope that the approach will allow regulatory approval and distribution in low- and middle-income countries. He added that these local entities, which he declined to name, share Lantu’s mission and were vetted for their technical capabilities.

“Given that these local entities operate in their own countries following their own regulatory requirements and medical and cultural practices, we are unable to have full knowledge regarding how they conduct their clinical programs for their own local approval and distribution,” Gao said.

One place the early-access program can be found: Indonesia, where the Murthy family traveled to in May.

Teck-Onn Lim, a doctor who oversaw the infusion of Aryan’s medicine at Tzu Chi Hospital, said outside accountability was provided by the hospital’s ethics review board. Asked about regulatory oversight, Lim didn’t know the name of the government body that approved the program, nor its criteria.

After being injected with Vesemnogene lantuparvovec, Aryan didn’t experience any major side effects. Since then, his parents have seen striking gains.

Aryan’s motor skills, which were in decline, have improved. It’s easier for him to do what he loves: draw, paint and write. He can move from lying down to sitting up on his own, and stand from a chair while holding on for support. Most recently, he managed to walk for about 20 seconds – roughly 20 to 25 steps – while grasping just one of his father’s fingers for balance.

“He wants to walk, he wants to run,” Murthy said.

Because it has only been a few months, Murthy is hopeful that his son will make further progress.

“We are there 75% to 80%. There’s still some distance to go. We are hopeful that we will get very close to 100%,” Murthy said.

The family’s experience echoes a Phase 1, uncontrolled study with 16 patients. Vesemnogene lantuparvovec improved motor function, according to

a preprint

that was published in August. In that study, the therapy was generally well tolerated.

Four patients had respiratory tract infections. One child with severe disease died, an outcome investigators attributed to the natural course of spinal muscular atrophy rather than the treatment.

The results of further clinical testing will determine whether the therapy is effective and safe enough to seek regulatory approval in various places.

Other Chinese companies working on Zolgensma alternatives include Exegenesis Bio, Skyline Therapeutics and GeneCradle.

GeneCradle is in a Phase 3 study and aims to obtain approval by late 2026 or early 2027 in China. Eventually, the company wants to reach more of the globe, with a therapy priced less than Zolgensma, according to a company spokesperson.

Outside China, US gene therapy pioneer Jim Wilson and his company, GemmaBio, struck up a partnership with Abu Dhabi’s government to produce more obtainable gene therapies, including for spinal muscular atrophy.

China has been a particular hotbed for this type of research, and not just because of its broader biotech boom. The country has a large rare disease population

underserved by current treatments

, a state prioritization of these conditions and advanced AAV manufacturing capabilities.

Several Chinese companies, like Legend Biotech, have brought cancer drugs to the world, though the country still hasn’t achieved a global gene therapy for a rare disorder.

Murthy is thankful that more options are starting to emerge.

“We never look at him as just a disease. He’s our son after all. We always tried to give him support,” he said.

上市批准临床3期临床1期基因疗法

2025-09-29

关注并星标CPHI制药在线

9月25日,据报道,渤健将终止基于腺相关病毒(AAV)的基因疗法研发。这家曾经重金押注AAV技术的药企巨头,最终加入了辉瑞、罗氏、武田和Vertex的撤退行列。

曾经备受追捧的AAV基因疗法赛道,如今却成了众多制药巨头急于剥离的“烫手山芋”。

AAV的现实瓶颈问题

AAV(腺相关病毒)作为基因治疗载体的核心优势在于其能够将功能性基因高效递送到特定细胞中,实现潜在的一次性治愈效果。理论上,这代表了遗传疾病治疗的终极目标。但是,现实中却面临着很多挑战和难题。

免疫原性问题是AAV技术面临的首要障碍。作为自然界存在的病毒,AAV在人群中普遍存在,许多患者体内已有预存抗体,这导致相当比例的患者无法从治疗中获益,因为他们的免疫系统会在药物到达靶细胞前就将其清除。

罗氏旗下Spark公司的研究显示,AAV2载体导致超过60%的患者产生新中和抗体。这一问题在需要全身给药的疾病中尤为突出。

递送效率与靶向性不足是另一大挑战。特别是对于需要跨越血脑屏障的神经系统疾病,AAV的“归巢”能力并不理想。以杜氏肌营养不良症(DMD)为例,由于AAV对肌肉靶向性差,只能通过超高剂量“覆盖”,其剂量是肝脏相关疾病疗法的数倍甚至数十倍。

高剂量给药带来的安全性问题已经导致多起严重事件,2025年,Sarepta Therapeutics的AAV基因疗法Elevidys在治疗DMD过程中导致三名患者因肝损伤死亡。据Norn Group统计,2021至2024年间,已有13例死亡与AAV基因疗法相关。

载荷容量限制同样制约了AAV的应用,AAV载体能携带的基因大小有限(<4.7kb),这对于治疗由大基因引起的疾病(如杜氏肌营养不良症)显得力不从心。虽然开发了重叠/反式剪接等双载体策略,但这些方法进一步增加了技术的复杂性和风险。

巨头的撤退路径

回过头看,渤健的AAV基因疗法撤退酝酿多时,2019年,公司以8.77亿美元溢价收购Nightstar Therapeutics,将两款AAV基因疗法纳入管线。但好景不长,2021年5月,其主打产品XIRIUS在II/III期临床中折,患者视力改善未达统计学显著差异。

紧随其后,另一款针对无脉络膜症的BIIB111疗法III期试验也宣告失败。两次关键临床失利直接导致渤健计提5.42亿美元资产减值,重创其战略布局。到2023年4月,渤健宣布终止三个临床项目,将基因治疗与眼科业务从核心管线中降级,全面削减高风险神经科学领域投入。

今年年初以来,AAV基因疗法领域迎来一波更为密集的巨头撤退潮。2月27日,Vertex终止与Verve Therapeutics价值4.66亿美元的肝病基因编辑合作。同期,辉瑞将用于治疗B型血友病的AAV基因疗法Beqvez撤市,这款2024年4月才获批的产品,因零患者使用而成为史上最快退市的基因治疗产品。

5月初,强生旗下潜在同类首创的AAV基因疗法bota-vec治疗X连锁视网膜色素变性的III期LUMEOS研究未能达到主要终点。这对强生无疑是一个沉重打击,2023年底,他们才以6500万美元首付款、4.15亿美元总价从MeiraGTx手中获得bota-vec的全球权益。

而罗氏最近正对旗下基因治疗部门Spark Therapeutics进行“根本性重组”,计提24亿美元商誉减值,裁撤337个岗位并将剩余310名员工并入母公司。曾经创下基因疗法领域最大金额并购案的Spark,如今已成为罗氏财务报表上的负担。

商业化困境

即便成功跨越研发障碍,AAV基因疗法面临的商业化困境同样令人望而却步。

天价定价,是首个门槛。目前上市的AAV基因疗法定价动辄在200万-300万美元之间。例如,诺华的Zolgensma定价高达212.5万美元,辉瑞的Beqvez定价350万美元。

信念医药的信玖凝®虽然单瓶价格只有9.3万元,但按体重算总价(比如70公斤患者需要44瓶,总价409.2万元),仍然是国内药品价格的前几名。

传统的B型血友病治疗需要终身注射凝血因子,一年花费大约40万元,七年累计费用就和基因疗法接近。虽然基因疗法一次静脉注射就可能长期有效,但高昂的初始成本还是让很多患者和医保系统难以承受。

商业保险覆盖不足也是AAV基因疗法难以大规模推广的原因之一。尽管诺华推出了按疗效付费等创新支付方式,但整体来看,医保机构对天价基因疗法的接受度仍然有限。

而对药企来说,投入高,市场空间却小。传统药物依赖长期用药创造持续收入,而基因疗法旨在“一劳永逸”,这要求企业在一个极短的时间窗口内回收巨额投资。辉瑞的Beqvez获批后根本没有患者接受商业化治疗,最后只能撤市。罗氏Spark的遗传性视网膜疾病基因疗法Luxturna在2023年销售额大跌59%,从2022年的5000万美元掉到大约2000万美元。许多基因疗法针对的是罕见病,患者基数小。即使单价再高,总市场天花板也可能有限。

AAV疗法真的没未来了吗?

大药企退出,并不代表AAV基因治疗领域就没有前途了,更可能意味着行业分工进一步细化。以后,更敢冒险的生物技术公司会主导早期探索,大药企则通过合作、收购等方式在后期介入。

“高风险、高回报”的研发模式正在发生转移,大药企可能更愿意避开早期技术不确定性,把基础研究和概念验证留给规模小、更灵活的Biotech公司。同时,“平台型”公司和“产品型”公司开始分道扬镳。那些专注于优化AAV载体本身(比如衣壳改造、生产工艺)的“平台型”公司,可能更具备长期价值。2021年,渤健曾与Capsigen公司合作,设计能递送转化基因疗法的新型AAV衣壳,预付款只有1500万美元。这种合作模式让大药企能用较低成本获取新技术,同时把早期风险转移给专业平台。

巨头退出,其实给专业化公司留出了发展空间。和跨国药企撤退形成对比的是,一些区域性公司正在这一领域取得进展,2025年4月,中国信念医药的信玖凝®(BBM-H901)获国家药监局批准,用于治疗B型血友病,成为国内第一款AAV基因治疗产品。锦篮基因的GC101注射液也进入了Ⅲ期临床,适应症覆盖1-3型脊髓性肌萎缩症全谱系患者。

并购活动可能随之活跃。渤健等公司的退出,可能是在清理管线、回笼资金,为未来收购那些在AAV技术上取得关键突破的明星Biotech做准备。类似案例在医药行业并不罕见,大药企往往等待生物技术公司验证技术可行性后,再通过收购介入。

结语

尽管巨头们纷纷在AAV赛道遇阻,但全球范围内,越来越多的AAV基因疗法研发项目仍在持续推进,众多药企纷纷布局,投入大量资金开展相关研发项目。

技术瓶颈的突破只是时间问题。随着新型衣壳工程改造显著提升靶向性与转导效率,CRISPR/Cas等基因编辑工具与AAV的深度融合,生产工艺的优化持续攻克大规模量产与成本控制的瓶颈,AAV基因疗法有望迎来新一轮发展浪潮。

我们还是对AAV基因治疗抱有信心。未来,相信这个领域会进入更理性的发展阶段,从追“热点”转向做“价值”,真正发挥出它作为革命性医疗技术的潜力。

参考信息:

[1]新药研发不易!礼来终止一项减重药临床试验,渤健终止AAV基因疗法研发. 药时代

[2]渤健终止AAV基因疗法研发;加科思董事长及一致行动人增持近1亿港币. 搜狐.

[3]AAV基因疗法遇信任危机:从Sarepta悲剧看技术十字路口.

[4]新一基因疗法III期临床研究结果失利. 智慧芽.

END

来源:CPHI制药在线

声明:本文仅代表作者观点,并不代表制药在线立场。本网站内容仅出于传递更多信息之目的。如需转载,请务必注明文章来源和作者。

投稿邮箱:Kelly.Xiao@imsinoexpo.com

▼更多制药资讯,请关注CPHI制药在线▼

点击阅读原文,进入智药研习社~

基因疗法临床3期并购

2025-08-21

·药事纵横

基因疗法是一种通过将外源正常基因导入到靶细胞内,来纠正或补偿由基因缺陷或基因表达异常所致的疾病,从而实现治疗疾病目的的生物医学手段。根据国际人类基因组组织(The Human Genome Organization, HUGO)的研究表明,基因疗法可以克服传统小分子和大分子抗体药物调控蛋白质水平的局限性。随着基因编辑技术、基因治疗技术和细胞治疗技术的飞速发展,以及人们对健康需求的增加,未来几年全球基因药物市场将继续保持高速增长。本文将结合最新数据,深入解析基因疗法的商业行情及其发展前景。

一、千亿蓝海的市场格局

1)全球市场概况

自2015年起,全球基因治疗行业迅猛发展,市场规模从2016年的5040万美元跃升至2020年的20.8亿美元,预计到2025年,该市场规模将逼近305亿美元。就区域分布而言,北美地区在全球基因治疗市场中占据最大份额,约为60%,该地区拥有超过600家致力于细胞和基因疗法产品研发的公司。紧随其后的分别是欧洲和亚太地区,市场占比分别为23%和12%。拉丁美洲在全球市场中的占比为3%,而其他地区则占2%。

图1.全球基因治疗市场规模(图片来源:中国生物工程杂志)

自1998年全球首款基因治疗药物问世以来,基因治疗药物的获批数量一直较为稀少,每年仅有一款药物获得批准。然而,自2016年起,基因治疗药物的全球商业化进程开始加速,平均每年约有四款基因治疗药物获批上市。截至2022年底,全球范围内已有45款基因治疗药物获得上市批准,这些药物主要针对罕见病,并以CAR-T疗法为主导。2024年上半年,全球共有3款细胞和基因疗法首次获批上市,获批数量保持近年来的积极趋势。其中,首款肿瘤浸润淋巴细胞(TIL)疗法Amtagvi(lifleucel)获得美国FDA批准,用于治疗晚期黑色素瘤,这是首款获批的TL疗法,也是首款获批治疗实体瘤的T细胞疗法,标志着细胞疗法领域的又一里程碑。从市场规模来看,贝哲斯咨询预测,2023-2029年全球基因治疗药物市场将保持较高的复合年增长率(CAGR),市场规模将从数亿美元增长至数十亿美元。

图2.基因治疗上市药物数量年度分布(图片来源:中国生物工程杂志)

2)中国市场概况

尽管中国在基因治疗领域的起步相对较晚,但已迅速崛起成为全球最重要的基因药物研发市场之一,累计进行的临床试验数量仅次于美国,位居全球第二。截至2023年,中国基因治疗药物市场规模已达数亿元人民币,已有多款国产基因治疗产品成功上市,包括重组人p53腺病毒注射液(商品名:今又生)、重组人5型腺病毒注射液(商品名:安柯瑞)、倍诺达以及西达基奥仑赛(商品名:CARVYKTI)等。预计到2025年,中国基因治疗行业市场规模将达到数百亿元,其中临床试验和产品上市将是主要增长动力。目前,国内布局细胞与基因治疗(CGT)业务的公司超过100家,其中复星凯特和药明巨诺均有产品上市。其他在研发管线数量上领先的企业还包括纽福斯、本导基因、锦篮基因、新芽基因、辉大基因、康弘药业等。

图3.部分中国基因治疗上市药物(图片来源:中国生物工程杂志)

二、基因疗法的主要技术与产品

基因疗法是一种前沿的医学技术,主要通过引入、修复或编辑患者体内的基因来治疗疾病,其主要技术包括基因编辑技术(如CRISPR/Cas9)、CAR-T细胞治疗和病毒载体疗法等。目前,市场上主要的产品包括用于治疗血液癌症的CAR-T细胞产品(如Kymriah和Yescarta),以及用于治疗Leber先天性黑蒙(LCA)的体内AAV基因治疗产品Luxturna。

1)基因治疗的主要技术

基因治疗的核心原理主要包括:

l基因替代:用健康的基因替代缺陷基因,使细胞能够产生正常功能的蛋白质。

l基因修复:通过基因编辑技术直接修复体内的突变基因,恢复其正常功能。常用的基因编辑工具有CRISPR-Cas9、ZFNs和TALENs。

l基因沉默:使用RNA干扰(RNAi)或反义寡核苷酸(ASO)技术抑制有害基因的表达,防止其产生病理性蛋白质。

l基因补充:为患者提供缺乏的基因产物(如特定酶或蛋白质),以补偿体内的生理缺陷。

2)基因治疗的产品

已研发出多类型的基因治疗产品,主要包括:

l质粒DNA:环状DNA分子可通过基因工程将治疗基因携带到人体细胞中。

l病毒载体:病毒具有将遗传物质传递到细胞中的天然能力,一些基因治疗产品源自病毒。一旦病毒被修饰以消除其引起传染病的能力,这些修饰的病毒就可以用作载体,将治疗基因携带到人类细胞中。

l细菌载体:细菌可经过改造以防止其引起传染病,然后用作载体将治疗基因携带到人体组织中。

l患者来源的细胞基因治疗产品:从患者体内取出细胞,进行基因改造(通常使用病毒载体),然后返回患者体内。

l基因编辑技术:基因编辑的目标是破坏有害基因或修复突变基因。

3)应用实例

lGlybera:由荷兰UniQure公司开发,用于治疗脂蛋白脂肪酶缺乏症,是第一款获得批准的AAV基因疗法。

lStrimvelis:由GSK开发,用于治疗腺苷酸脱氢酶(ADA)缺失导致的严重联合免疫缺陷(SCID)。

lLuxturna:由Spark Therapeutics开发,用于治疗RPE65双等位基因突变导致的遗传性视网膜疾病先天性黑朦症II型(Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis, LCA)。

由此可见,基因疗法作为疾病的“治本”疗法,正成为新药研发的下一个风口,尤其是在遗传性疾病、癌症、罕见病以及某些感染性疾病的治疗中展现出巨大的潜力。

三、基因疗法应用领域

基因疗法是一种前沿的医学治疗方式,通过直接修改患者的基因来治疗疾病。

1)基因疗法的应用领域

l遗传性疾病

基因疗法在遗传性疾病的治疗中显示出巨大的潜力。例如,针对囊性纤维化、地中海贫血、杜氏肌营养不良症等,通过修复或替换异常基因,基因疗法能够显著改善患者的症状。

l癌症治疗

在癌症治疗领域,基因疗法主要通过两种方式发挥作用:一是修复或替换导致肿瘤生长的异常基因;二是通过基因编辑刺激患者免疫系统,增强机体对肿瘤细胞的识别和攻击能力。例如,CAR-T细胞疗法已经成为治疗某些类型白血病和淋巴瘤的有效手段。

l病毒性疾病

对于艾滋病、乙型肝炎等病毒性疾病,基因疗法可以通过编辑病毒基因来阻止病毒复制和感染。这种方法可以直接针对病毒生命周期中的特定基因,提供潜在的治疗策略。

l心血管疾病和其他

基因疗法还应用于心血管疾病,如家族性高胆固醇血症,通过修改低密度脂蛋白受体的基因来降低胆固醇水平。此外,基因疗法也在探索用于神经系统疾病如帕金森病和亨廷顿病的治疗。

2)各大药企的产品布局

基因疗法作为一种新型的生物医疗技术,近年来受到全球各大药企的广泛关注和投资。

lBioMarin

BioMarin在基因疗法领域专注于罕见病治疗,尤其是血友病。他们的产品Roctavian(用于治疗法布雷病)已进入三期临床,并且正在考虑与诺和诺德合作开发用于A型血友病的CAR-T疗法。BioMarin还在持续优化其基因疗法策略,以降低治疗成本和提高治疗效果。

lModerna

Moderna以其在mRNA技术方面的领先地位,开发了多种疫苗和疗法。其产品mRNA-1273用于COVID-19疫苗,而mRNA-4157则用于联合Keytruda(帕博利珠单抗)治疗皮肤癌。此外,Moderna正在开发一种“通用型”流感疫苗,旨在提供对不同流感病毒的广泛保护。

lBluebird Bio

Bluebird Bio曾是基因治疗领域的先锋,专注于开发针对严重遗传疾病和癌症的基因疗法。其核心产品包括Zynteglo、Skysona和Lyfgenia,这些产品主要用于治疗地中海贫血、脑肾上腺脑白质营养不良和镰状细胞病。尽管面临高成本和安全性问题,Bluebird Bio的产品在市场上获得了一定的关注。

l赛诺菲

赛诺菲通过收购Bioverativ进入基因疗法领域,重点发展血友病的基因治疗产品。此外,赛诺菲与Oxford BioMedica合作开发基于慢病毒载体的基因治疗产品,预计将于2022年进入临床阶段。赛诺菲还在与多家公司和研究机构合作,扩展其在基因疗法领域的布局。

l其他药企巨头

除此之外,辉瑞布局了包括A型血友病、B型血友病、杜氏肌营养不良症等多个基因治疗领域;罗氏收购了Spark Therapeutics,获得了多项基因疗法技术,如Luxturna,用于治疗特定遗传性眼疾;吉利德科学则在T细胞治疗领域有着广泛的布局,其Yescarta和Kymriah是市场上的知名CAR-T产品;强生还收购了Hemera生物科学公司的基因疗法专利权,专注于眼部疾病的基因治疗。

四、抢滩AAV基因疗法

基因疗法根据涵盖范围的不同,可分为广义与狭义两种,涉及多种治疗项目。在广义上,细胞和基因治疗被统称为细胞基因治疗(CGT),这是我们通常所说的广义基因治疗。例如,辉瑞的Beqvez就是一种基于腺相关病毒(AAV)的基因疗法,而蓝鸟生物目前拥有三款获批的基因疗法产品,包括两款慢病毒载体(LVV)基因疗法和一款CAR-T细胞疗法。狭义的基因疗法则专指基因递送治疗,其中以病毒和质粒DNA为载体的基因治疗产品较为常见,常用的病毒载体包括腺病毒(AdV)、腺相关病毒(AAV)、逆转录病毒(RV)和慢病毒(LV)。近年来,以AAV为载体的基因治疗因其技术优势逐渐成为研究热点之一,尤其是自2017年FDA批准罗氏/Spark Therapeutics的Luxturna以来,该领域的发展开始加速,截至目前,全球已有超过10款基因治疗产品获批上市。

图4.全球获批的基因治疗产品(图片来源:沙利文分析)

2012年获批的Glybera是第一个基于AAV载体的基因疗法。2017年,FDA批准Luxturna在美国上市,成为获批的首款体内给药式基因疗法。2022年FDA批准蓝鸟的体外基因改造细胞疗法Zynteglo用于需要输血的成人和儿童地中海贫血症患者的治疗,这是针对这一患者群体首款批准的基因疗法。值得一提的是,目前国内药企已有多个研究管线推进至关键临床阶段,预计近期将有产品获批上市。例如,天泽云泰利用其自主知识产权的ViVec® AAV载体筛选平台,研发了多款创新基因治疗产品,其中VGB-R04和VGM-R02b等三款产品已陆续进入临床阶段,并荣获FDA的罕见儿科疾病认定(RPDD)和孤儿药认定(ODD)。这些成就不仅彰显了中国在基因治疗领域的研发实力,也为全球罕见病治疗提供了新的希望。

五、国内企业加速布局基因疗法产品

作为全球生物医药产业竞争最重要的“新赛道”之一,国内各大药企在细胞与基因治疗领域展现出了强劲的创新活力。近年来,国内药企在基因疗法产品布局方面近年来显示出积极的态势,在基因疗法领域的布局正在加速,尤其是在基因编辑、细胞疗法和病毒载体治疗等领域。

1)基因编辑技术

国内药企如博雅辑因和纽福斯等技术领军企业,专注于利用CRISPR/Cas9和单碱基编辑技术开发治疗血液疾病、遗传性疾病及癌症的创新疗法。这些公司通过自体和异体细胞疗法实现疾病的一次性治愈潜力,覆盖广泛的疾病领域,包括血液瘤、实体瘤和遗传代谢性疾病。

2)细胞治疗

细胞治疗是基因疗法的另一重要领域,国内药企如复星医药、恒瑞医药和百济神州等已在癌症基因疗法领域加大研发投入。这些企业的研发总投入在2023年超过80亿元人民币,预计到2025年将突破120亿元人民币,显示出对基因疗法的高度重视和长期看好。

3)市场价值和应用

基因疗法市场价值极高,尤其是在特定罕见病和难治性癌症的治疗上。例如,CAR-T细胞疗法在血液瘤和淋巴系统肿瘤的治疗上已显示出显著效果,市场规模持续增长。随着技术进步和监管体系的逐步完善,基因疗法的商业化速度和市场接受度预计将进一步提高。

国产基因治疗产品在适应症覆盖上展现出广泛性,涉及眼病、血液病、代谢病、神经系统疾病等多个领域。在技术探索上,国内企业勇于创新,许多产品凭借坚实的技术基础和数据分析,成功走出国门,获得了美国FDA的孤儿药认定、儿童罕见病疗法认定以及突破性疗法等资质。目前,国内已经推进到临床试验阶段的国产基因治疗产品已经超过80款,绝大多数仍然处于早期临床试验阶段,少数已经进入确证临床试验(III期)。值得注意的是,信念医药的B型血友病基因治疗已在2024年7月向国家药品监督管理局(NMPA)递交上市申请,成为首个申请上市的国产基因治疗产品。

六、商业化前景与投资机会

商业化前景方面,基因疗法技术不断发展,如高通量测序、全外显子测序、无创产前检测等,提高了对遗传病、基因组学的认知,为基因疗法的商业化提供了基础。同时,基因治疗为遗传性疾病和难治性疾病提供了新的治疗选择,具有巨大的市场需求。尤其是在中国,随着经济增长和对医疗健康需求的增加,为基因疗法提供了更广阔的患者样本和市场空间。此外,多个国家和地方政府出台支持和规范基因治疗发展的政策,例如中国出台了《“十四五”规划和2035年愿景目标纲要》等相关政策,为基因疗法的发展提供了良好的政策环境。

投资机会方面,技术创新主要关注基因编辑技术如CRISPR-Cas9的持续优化,以及新型基因载体系统的开发,如腺相关病毒载体(AAV)的改进。此外,投资于早期基因疗法产品主要集中于遗传性疾病的治疗,如血液疾病、免疫系统疾病等,并逐步扩展至神经性疾病、癌症以及罕见病领域。同时,基因疗法研究的投资热度不断升温,全球范围内,众多生物技术公司、医药巨头以及投资机构纷纷布局基因疗法领域,推动该领域的快速发展。

依据中商产业研究院发布的《2017-2027全球及中国细胞和基因疗法药物输送装置行业深度研究报告》数据显示,全球基因治疗行业市场规模自2016年开始飞速增长。全球基因治疗市场的增长主要受到个性化医疗需求的增加、慢性疾病和罕见病的高发率以及细胞与基因治疗研究和开发的持续投入等因素的推动。根据最新的市场研究,全球基因治疗市场的规模在近年来呈现快速增长的态势。此外,中国市场也在积极发展基因治疗业务,依据中商产业研究院发布的《2024-2029全球及中国细胞和基因疗法药物输送装置行业深度研究报告》显示,2023年中国基因治疗行业市场规模达到约33.81亿元,较上年增长113.64%。据预测,到2025年,中国的基因治疗市场规模将超过100亿元人民币。这表明,中国在全球基因治疗市场中占据了重要的位置,并预计将持续扩大其市场影响力。这些数据显示出基因治疗领域的全球产业正在迅速扩张,预示着该行业未来在这一领域将继续保持强劲的增长势头。

图5.中国市场规模及预测(图片来源:中商产业研究院)

七、总结

总的来说,基因治疗作为医疗领域的璀璨新星,正以前所未有的速度改变着我们对疾病治疗的认知与实践。基因疗法药物市场正处于快速发展阶段,技术创新和政策支持为市场的发展提供了强大的动力。各大药企在基因治疗领域的布局,推动了行业规模的不断扩大。未来,随着技术的不断进步和市场需求的增长,基因疗法药物市场将迎来更加广阔的发展前景!

参考资料:

[1] 企业研发日报告、年度报告、季度业绩报告、研发管线报告.

[2] 冯雪娇,衡超,于新语,等.基因治疗行业市场分析及展望[J].中国生物工程杂志,2023,43(06):102-112.

[3] 中商产业研究院,《2017-2027全球及中国细胞和基因疗法药物输送装置行业深度研究报告》

[4] 中商产业研究院,《2024-2029全球及中国细胞和基因疗法药物输送装置行业深度研究报告》

立即扫码加入药事纵横交流群

细胞疗法基因疗法上市批准免疫疗法ASH会议

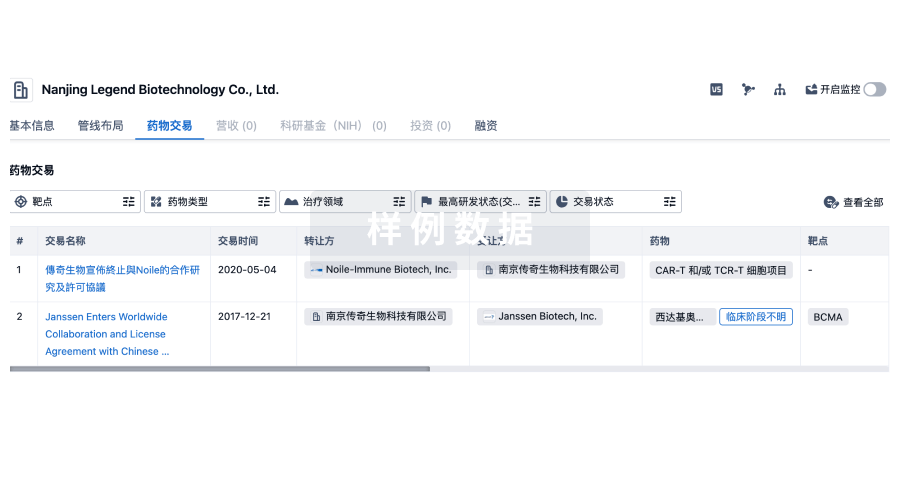

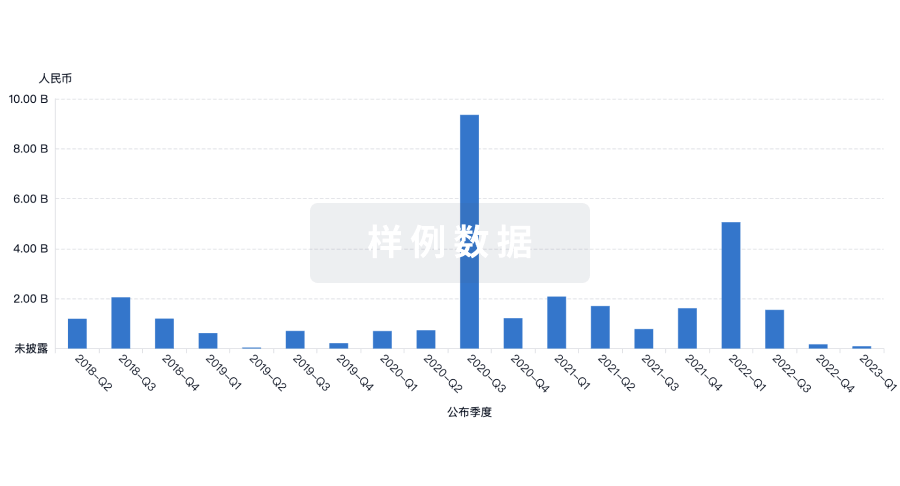

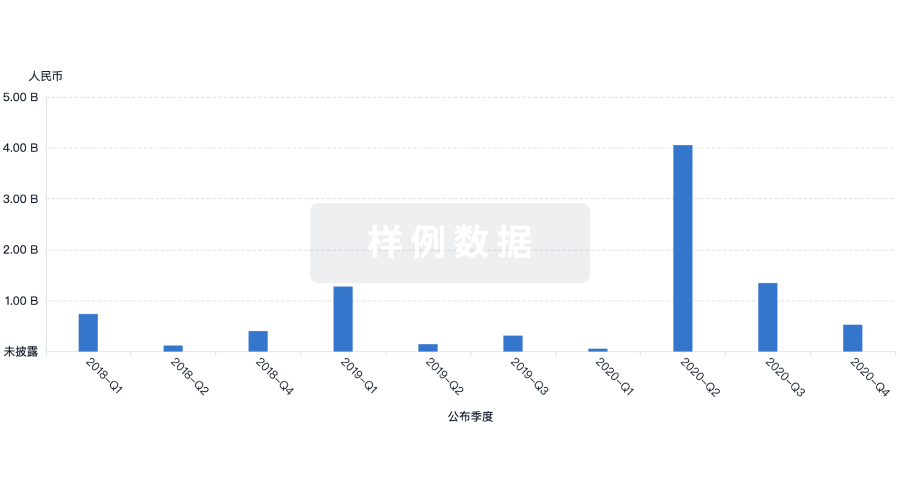

100 项与 北京锦篮基因科技股份有限公司 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

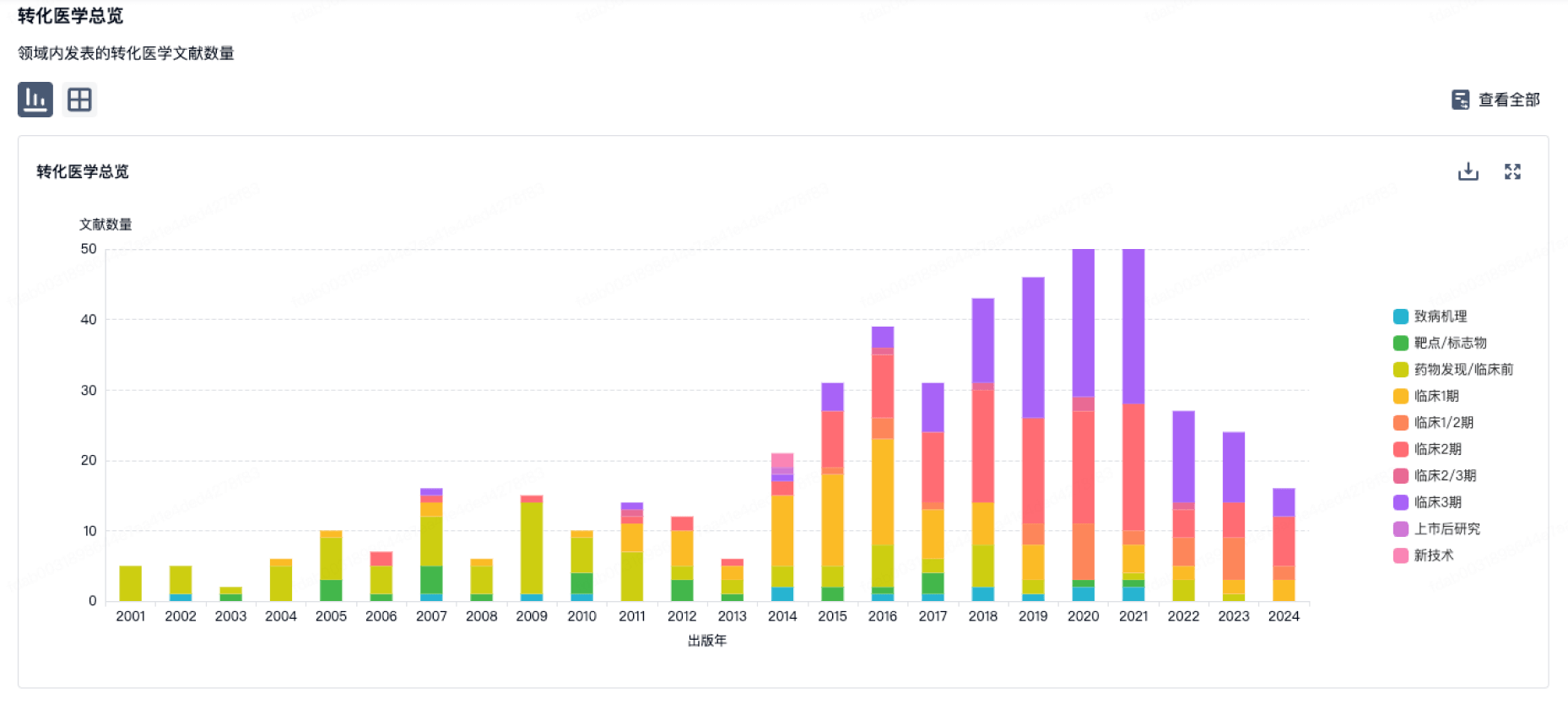

100 项与 北京锦篮基因科技股份有限公司 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

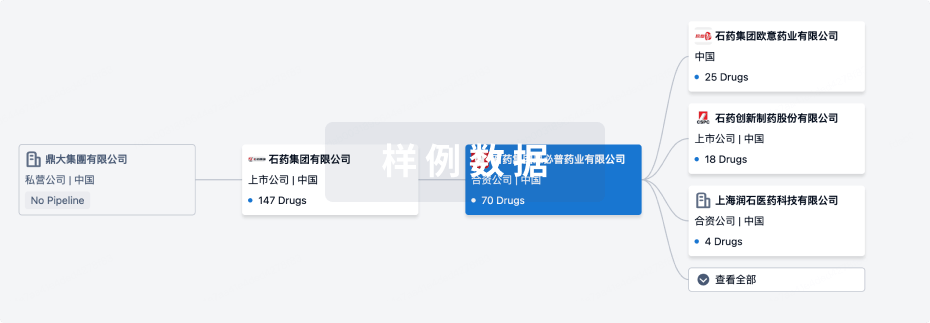

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2025年11月02日管线快照

管线布局中药物为当前组织机构及其子机构作为药物机构进行统计,早期临床1期并入临床1期,临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

药物发现

3

2

临床前

临床1期

1

2

临床2期

临床3期

1

3

其他

登录后查看更多信息

当前项目

| 药物(靶点) | 适应症 | 全球最高研发状态 |

|---|---|---|

GC101腺相关病毒 ( SMN1 ) | I型脊髓性肌萎缩症 更多 | 临床1/2期 |

GC-310 ( ATP7B ) | 肝豆状核变性 更多 | 临床1/2期 |

GC301腺相关病毒 ( α-glucosidase ) | II型糖原贮积病 更多 | 临床1/2期 |

GC304腺相关病毒 | 胰腺炎 更多 | 临床1期 |

GC-311 ( ABCD1 ) | 肾上腺脑白质营养不良 更多 | 临床前 |

登录后查看更多信息

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

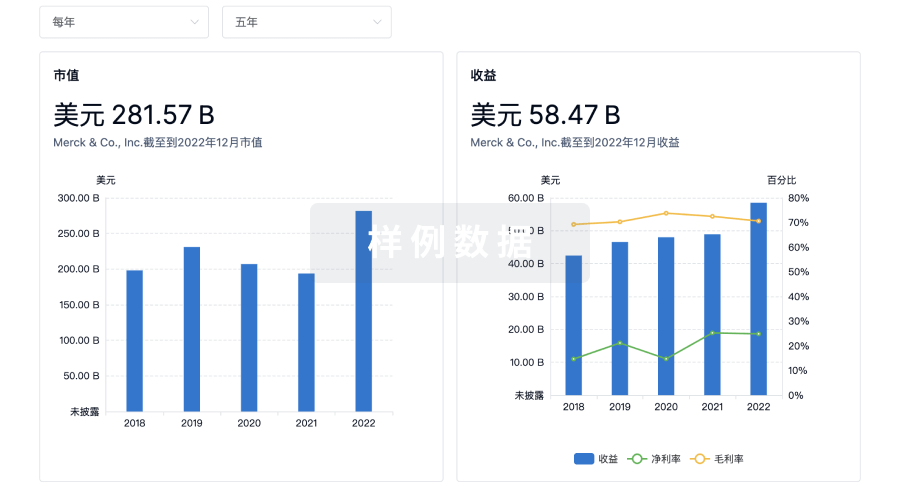

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用