预约演示

更新于:2025-10-24

Tuvusertib

更新于:2025-10-24

概要

基本信息

原研机构 |

非在研机构- |

权益机构- |

最高研发阶段临床2期 |

首次获批日期- |

最高研发阶段(中国)临床1期 |

特殊审评- |

登录后查看时间轴

结构/序列

分子式C16H12F2N8O |

InChIKeyRBQPCTBFIPVIJN-UHFFFAOYSA-N |

CAS号1613200-51-3 |

关联

18

项与 Tuvusertib 相关的临床试验NCT06337630

A Phase I Study on Tuvusertib (Oral ATR Inhibitor) in Combination With PLX038 (Topo1 Inhibitor) With Dose Expansion Cohorts in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors

Phase I with a dose finding cohort, followed by expansion cohorts in pre-specified tumor types.

开始日期2025-01-20 |

申办/合作机构  Institut Curie Institut Curie [+2] |

CTIS2023-505431-12-00

- IC 2022-10

开始日期2025-01-20 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06518564

A Phase 2 Study of Avelumab in Combination With ATR Inhibitor M1774 in Patients With ARID1A-mutated Recurrent Endometrial Cancer Who Have Received Prior Immunotherapy

The purpose of this research study is to see if the combination of study drugs avelumab and M1774 is effective and safe for participants with endometrial cancer.

The names of the study drugs involved in this study are:

* Avelumab (a type of human IgG1 antibody)

* M1774 (a type of ATR inhibitor)

The names of the study drugs involved in this study are:

* Avelumab (a type of human IgG1 antibody)

* M1774 (a type of ATR inhibitor)

开始日期2024-11-14 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 Tuvusertib 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

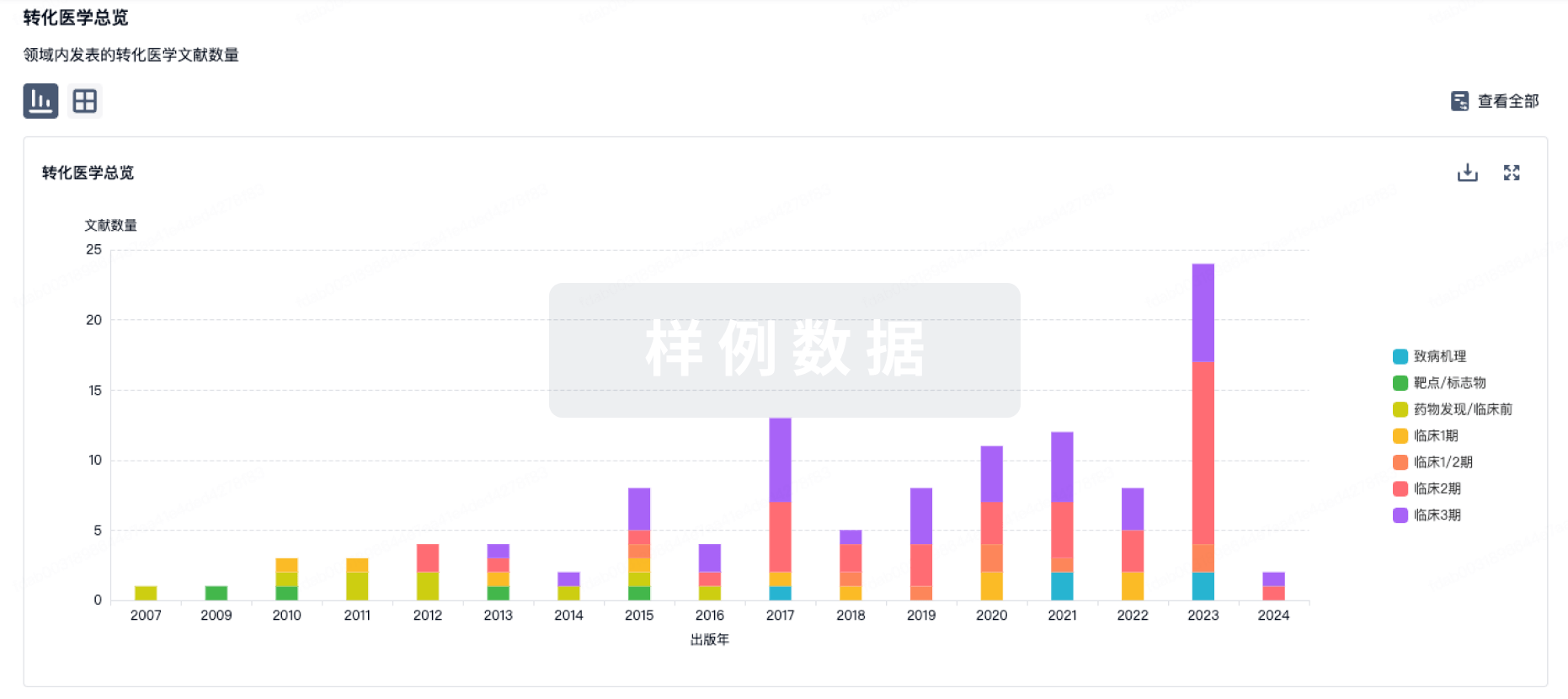

100 项与 Tuvusertib 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

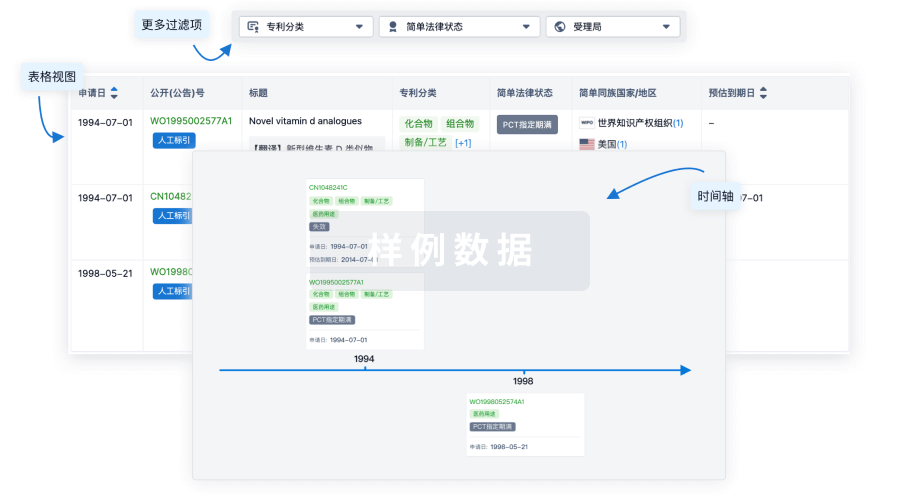

100 项与 Tuvusertib 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

6

项与 Tuvusertib 相关的文献(医药)2025-07-01·BIOMEDICAL CHROMATOGRAPHY

Quantitation of Tuvusertib (M1774) in Human Plasma by LC‐MS/MS

Article

作者: Holleran, Julianne L. ; Le, Tien V. ; Beumer, Jan H. ; Bakkenist, Christopher J. ; Feng, Ye ; Cote, Gregory M. ; Parise, Robert A. ; Gore, Steven D. ; Synold, Timothy

ABSTRACT:

Ataxia‐telangiectasia and Rad3‐related (ATR) protein kinase is an essential regulator of the DNA damage response (DDR) at stalled and collapsed replication forks. Tuvusertib (M1774) is a selective, orally available small molecule ATR inhibitor currently in preclinical and clinical development for cancer treatment. This study presents a robust and simple 5‐min assay designed for the quantification of single agent tuvusertib in human plasma utilizing liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC‐MS/MS). A 20 μL volume of plasma was subjected to protein precipitation, followed by chromatographic separation using a Phenomenex Synergi Polar‐RP (4 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm) and a gradient mobile phase system consisting of 0.1% formic acid in both water and acetonitrile during a 4‐min run time. Mass spectrometric detection was achieved using a SCIEX 6500+ tandem mass spectrometer with electrospray positive‐mode ionization. With a stable isotopic internal standard, our assay met the criteria outlined by the Food and Drug Administration guidance for bioanalytical method validation, demonstrating robust performance within the range from 5 to 5000 ng/mL. This assay will support ongoing and future clinical studies by defining tuvusertib pharmacokinetics.

2024-12-01·BRITISH JOURNAL OF HAEMATOLOGY

Combined MEK1/2 and ATR inhibition promotes myeloma cell death through a STAT3‐dependent mechanism in vitro and in vivo

Article

作者: Canevarolo, Rafael R. ; Kmieciak, Maciej ; Shain, Kenneth H. ; Meads, Mark B. ; Grant, Steven ; Nkwocha, Jewel ; Li, Lin ; Silva, Ariosto S. ; Hu, Xiaoyan ; Alugubelli, Raghunandan R. ; Zhou, Liang ; Sudalagunta, Praneeth R. ; Mann, Hashim

Summary:

Mechanisms underlying potentiation of the anti‐myeloma (MM) activity of ataxia telangiectasia Rad3 (ATR) antagonists by MAPK (Mitogen‐activated protein kinases)‐related extracellular kinase 1/2 (MEK1/2) inhibitors were investigated. Co‐administration of the ATR inhibitor (ATRi) BAY1895344 (BAY) and MEK1/2 inhibitors, for example, cobimetinib, synergistically increased cell death in diverse MM cell lines. Mechanistically, BAY and cobimetinib blocked STAT3 Tyr705 and Ser727 phosphorylation, respectively, and dual dephosphorylation triggered marked STAT3 inactivation and downregulation of STAT3 (Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) downstream targets (c‐Myc and BCL‐X

L

). Similar events occurred in highly bortezomib‐resistant (PS‐R) cells, in the presence of patient‐derived conditioned medium, and with alternative ATR (e.g. M1774) and MEK1/2 (trametinib) inhibitors. Notably, constitutively active STAT3 c‐MYC or BCL‐X

L

ectopic expression significantly protected cells from BAY/cobimetinib. In contrast, transfection of cells with a dominant‐negative form of STAT3 (Y705F) sensitized cells to cobimetinib, as did ATR shRNA knockdown. Conversely, MEK1/2 knockdown markedly increased ATRi sensitivity. The BAY/cobimetinib regimen was also active against primary CD138

+

MM cells, but not normal CD34

+

cells. Finally, the ATR inhibitor/cobimetinib regimen significantly improved survival in MM xenografts, including bortezomib‐resistant models, with minimal toxicity. Collectively, these findings suggest that combined ATR/MEK1/2 inhibition triggers dual STAT3 Tyr705 and Ser727 dephosphorylation, pronounced downregulation of cytoprotective targets and MM cell death, warranting attention as a novel therapeutic strategy in MM.

2024-10-01·CTS-Clinical and Translational Science

Asia‐inclusive drug development leveraging principles of ICH E5 and E17 guidelines: Case studies illustrating quantitative clinical pharmacology as a foundational enabler

Review

作者: Kuroki, Yoshihiro ; Venkatakrishnan, Karthik ; Bolleddula, Jayaprakasam ; Dong, Jennifer ; Strotmann, Rainer ; Lu, Hong ; Klopp‐Schulze, Lena ; Mukker, Jatinder Kaur ; Gao, Wei ; Terranova, Nadia ; Li, Dandan ; Goteti, Kosalaram

Abstract:

With the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) E17 guidelines in effect from 2018, the design of Asia‐inclusive multiregional clinical trials (MRCTs) has been streamlined, thereby enabling efficient simultaneous global development. Furthermore, with the recent regulatory reforms in China and its drug administration joining the ICH as a full regulatory member, early participation of China in the global clinical development of novel investigational drugs is now feasible. This would also allow for inclusion of the region in the geographic footprint of pivotal MRCTs leveraging principles of the ICH E5 and E17. Herein, we describe recent case examples of model‐informed Asia‐inclusive global clinical development in the EMD Serono portfolio, as applied to the ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3‐related inhibitors, tuvusertib and berzosertib (oncology), the toll‐like receptor 7/8 antagonist, enpatoran (autoimmune diseases), the mesenchymal–epithelial transition factor inhibitor tepotinib (oncology), and the antimetabolite cladribine (neuroimmunological disease). Through these case studies, we illustrate pragmatic approaches to ethnic sensitivity assessments and the application of a model‐informed drug development toolkit including population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling and pharmacometric disease progression modeling and simulation to enable early conduct of Asia‐inclusive MRCTs. These examples demonstrate the value of a Totality of Evidence approach where every patient's data matter for de‐risking ethnic sensitivity to inter‐population variations in drug‐ and disease‐related intrinsic and extrinsic factors, enabling inclusive global development strategies and timely evidence generation for characterizing benefit/risk of the proposed dosage in Asian populations.

20

项与 Tuvusertib 相关的新闻(医药)2025-06-14

·医药观澜

根据中国国家药监局药品审评中心(CDE)官网以及公开资料梳理,本周(6月9日~6月14日),有16款1类创新药首次在中国获得临床试验默示许可(IND)。这些产品涵盖了抗体偶联药物(ADC)、小分子药物、抗体药物等类型,拟定适应症涵盖癌症、罕见病、肾脏疾病等等。图片来源:123RF辉瑞(Pfizer):PF-07985045片作用机制:小分子KRAS抑制剂适应症:携带KRAS突变的晚期实体瘤辉瑞申报的1类新药PF-07985045片获批临床,拟开发治疗携带KRAS突变的晚期实体瘤。根据辉瑞公开资料介绍,这是一款新一代小分子KRAS抑制剂类药物。辉瑞目前正在美国、日本等国家开展1期临床研究,评估PF-07985045片单独或与其他抗癌疗法一起用于KRAS突变的晚期实体瘤患者,包括非小细胞肺癌、结直肠癌、胰腺癌等。argenx:empasiprubart注射用浓溶液作用机制:补体C2抑制剂适应症:成人多灶性运动神经病(MMN)argenx公司申报的1类新药empasiprubart注射用浓溶液获批临床,拟开发治疗成人多灶性运动神经病(MMN)。公开资料显示,Empasiprubart (ARGX-117)被设计为一款人源化“清除抗体”(sweeping antibodies),以pH-和Ca2+依赖的方式特异性结合C2。C2是补体级联中的一种蛋白质,empasiprubart旨在抑制C2和下游补体激活的功能,从而减少组织炎症和适应性免疫反应。在国际范围内,该产品针对成人多灶性运动神经病适应症正处于3期临床研究阶段。该抗体的设计旨在增强抗体与内体中FcRn的结合,防止抗体进入溶酶体降解。良远生物医药:注射用人白介素-2(高亲和型复合物)作用机制:白介素-2适应症:晚期实体瘤良远生物医药申报的1类新药注射用人白介素-2(高亲和型复合物,研发代号LYC001)获批临床,拟开发治疗晚期实体瘤。公开资料显示,这是一款采用高亲和层级组装(High Affinity Hierarchical Assembly)技术平台研发的针对多种实体肿瘤的全新药物,该平台旨在通过淋巴系统给药的药物递送技术,解决现有大分子药物通过血液循环进行分布而导致的稳定性低、特异性差等问题,能够显著提高白介素-2的溶解度和稳定性。该产品以淋巴系统为靶标,皮下给药后由组织淋巴管收集,经逐级淋巴结和各级淋巴管后汇集于淋巴总管进入血液循环(生物利用度大于90%)。Tempest Therapeutics:TPST-1120片作用机制:小分子PPAR⍺拮抗剂适应症:肝细胞癌Tempest Therapeutics公司申报的1类新药TPST-1120片获批临床,拟用于既往未接受过系统性治疗的不可切除或转移性肝细胞癌患者。公开资料显示,这是一款口服、选择性小分子PPAR⍺拮抗剂。该产品可直接杀死肿瘤细胞,并靶向肿瘤微环境中的抑制性免疫通路。这两种类型中的靶向细胞皆依赖脂肪酸代谢,该代谢过程由PPARα转录因子调节。赛诺哈勃药业、倍特药业:SNH-119014片作用机制:小分子丙酮酸激酶激动剂适应症:血红蛋白病倍特药业及旗下赛诺哈勃药业申报的1类新药SNH-119014片获批临床,拟开发治疗血红蛋白病 (包括但不限于地中海贫血及镰状细胞病)。公开资料显示,这是赛诺哈勃药业研发的一款全新小分子丙酮酸激酶激动剂,该产品可明显提高丙酮酸激酶活性,增加生物标志物腺嘌呤核苷三磷酸(ATP)水平、降低2,3-二磷酸甘油酸(2,3-DPG)含量,满足患者红细胞的能量代谢需求,有望改善贫血、提高患者生活质量。礼新医药:LM-168注射液作用机制:抗CTLA-4抗体适应症:晚期实体瘤礼新医药申报的1类新药LM-168注射液获批临床,拟开发治疗晚期实体瘤。公开资料显示,LM-168是一款抗CTLA-4抗体。该产品经过工程化改造,可在肿瘤微环境(TME)中高ATP/ADP/AMP(ANP)水平下选择性结合CTLA-4,而在健康组织中结合力较弱,从而降低“脱靶毒性”。根据2025年AACR大会公布的研究结果,通过条件性靶向CTLA-4,LM-168旨在解决现有抗CTLA-4抗体面临的效价与耐受性挑战,有望成为兼具临床疗效与低毒性的下一代CTLA-4靶向疗法。此外,该药物预计可与抗PD-1/PD-L1疗法产生协同效应。乐普生物:MRG007作用机制:靶向CDH17的ADC适应症:局部晚期或转移性实体瘤乐普生物1类新药MRG007获批临床,拟开发治疗局部晚期或转移性实体瘤。公开资料显示,这是一款靶向CDH17的抗体偶联药物(ADC),由新型人源化IgG1抗体通过定点偶联细胞毒素Exatecan而成。今年1月,ArriVent BioPharma以一项超12亿美元合作获得该产品在大中华区以外地区开发、制造和商业化的全球独家许可。根据研究人员在今年AACR年会上公布的研究结果,MRG007具有平衡的药物抗体比(DAR),差异化设计有望提升抗肿瘤疗效并拓宽治疗窗。金赛药业:GenSci134注射液作用机制:生物制品1类新药适应症:成人生长激素缺乏症金赛药业申报的1类新药GenSci134注射液获批临床,拟开发治疗成人生长激素缺乏症。根据长春高新公告介绍,这是一款治疗用生物制品1类药物。生长激素缺乏症可在一生中各个阶段发生。成人生长激素缺乏常合并多种并发症,带来诸多危害,且患者可能需要长期甚至终身替代治疗,存在未被满足的临床需求。德国默克:lartesertib片剂、tuvusertib胶囊/片剂作用机制:ATM抑制剂、ATR抑制剂适应症:卵巢上皮癌德国默克(Merck KGaA)申报的lartesertib片剂和tuvusertib胶囊/片剂获批临床,拟定适应症为:tuvusertib联合尼拉帕利或lartesertib治疗在既往PARP抑制剂治疗期间疾病进展的BRCA突变和/或同源重组缺陷(HRD)阳性卵巢上皮癌患者。公开资料显示,tuvusertib是一款ATR抑制剂,lartesertib (M4076)是一款ATM抑制剂。研究显示,在ATM缺失的肿瘤细胞中,ATR抑制剂可以产生合成致死效应,在导致ATM缺失肿瘤细胞死亡的同时,并不影响正常细胞。此外,ATR抑制剂还能与PARP抑制剂联合以增强治疗敏感性。在国际范围内,这款联合疗法已经进入2期临床研究阶段。除了上述产品,本周首次在中国获批IND的1类新药还包括:济煜医药申报的化药1类新药JMKX005425片获批临床,拟开发治疗微卫星高度不稳定型或错配修复缺陷型晚期实体瘤;维眸生物申报的1类新药VVN432鼻喷雾剂,拟开发治疗慢性鼻窦炎(CRS);舶望制药申报的化药1类新药BW-40202注射液获批临床,拟用于治疗补体介导的肾病,包括免疫球蛋白A肾病(IgA肾病)等;云白药征武科技申报的化药1类新药JZ-14胶囊,拟开发治疗溃疡性结肠炎;英创医药科技有申报的1类新药IGP-14068-TM片获批临床,拟用于治疗晚期实体瘤(包括但不限于高级别浆液性卵巢癌和三阴性乳腺癌等);微能生命科技申报的1类新药VPD/FC01002 注射液获批临床,拟开发治疗免疫重建不全等。期待这些在研新药后续临床研发进程顺利,早日为患者带来新的治疗选择。参考资料:[1]中国国家药监局药品审评中心(CDE)官网. Retrieved Jun 14, From https://www.cde.org.cn/main/xxgk/listpage/4b5255eb0a84820cef4ca3e8b6bbe20c[2]各公司官网及公开资料版权说明:本文欢迎个人转发至朋友圈,谢绝媒体或机构未经授权以任何形式转载至其他平台。转载授权或其他合作需求,请联系wuxi_media@wuxiapptec.com。免责声明:本文仅作信息交流之目的,文中观点不代表药明康德立场,亦不代表药明康德支持或反对文中观点。本文也不是治疗方案推荐。如需获得治疗方案指导,请前往正规医院就诊。

抗体药物偶联物申请上市临床3期临床2期临床1期

2025-04-29

Artios Pharma, a startup developing drugs that weaken a tumor’s ability to maintain its DNA, announced positive results in a subset of patients with advanced cancer. It’s the first big data reveal for the Cambridge, UK-based startup, which has been relatively quiet since 2021, when it struck a drug discovery partnership with Novartis and raised $153 million in Series C financing.

The company’s drug, called ART0380, inhibits a DNA repair enzyme called ATR. When administered with a low dose of the chemotherapy irinotecan, the drug shrank tumors in 37% of patients whose cancer was considered “deficient” in another DNA damage response protein dubbed ATM, according to data from a Phase 1/2 study.

In patients whose tumors lacked the ATM protein entirely, the response rate was 50%, with a median duration of response of 5.7 months so far. The response rate was 22% in patients with low levels of ATM.

Patients with the ATM protein, however, did not respond to the therapy. “All those patients unfortunately progress quickly and unfortunately die very quickly,” Artios Chief Medical Officer Ian Smith told

Endpoints News

in an interview.

The new data, presented Tuesday at the American Association for Cancer Research meeting, comes from 58 patients with advanced-stage and metastatic solid tumors who were treated at the dose the company plans to use in a Phase 2 study.

Artios CEO Niall Martin told Endpoints that the company has funds “through 2026.” He said the startup is looking to raise another round of private funding to test its ATR inhibitor in pancreatic and colorectal cancers before pursuing bigger and broader tissue-agnostic studies.

Martin said the company’s partnership with Novartis, which wasn’t focused on its ATR inhibitor, identified several targets that could potentially be paired with Novartis’

radioligand therapies, including its prostate cancer drug Pluvicto, and discussions are underway on next steps. Artios had struck a

partnership

with Merck KGaA in 2020 to search for drugs that target other DNA repair proteins, but Martin told Endpoints that partnership has ended.

Artios was founded in 2016 to discover a new wave of drugs that target complex networks of proteins dedicated to the faithful replication and preservation of our genomes. While cancer can survive, and even thrive, with some DNA repair enzymes missing, too many missing pieces can cause the cancer to self-destruct.

A class of drugs called PARP inhibitors exploit this vulnerability by blocking the eponymous DNA repair protein in tumors that have mutations in genes called BRCA1 and BRCA2, which are also important for DNA repair. Several companies have been searching for the next combination of targets that can deliver a similar double whammy to tumors, but progress has been slow.

“The field hasn’t really evolved much since PARP inhibitors,” Martin said. “So we’ve been really thinking about what are the layers of DNA damage that are created in tumors that could be used as their sort of Achilles heel.”

One of those layers, according to Artios, is a phenomenon called replication stress, which can occur when DNA replication, a key step for dividing cells, is blocked. ATR and ATM are two proteins that detect and clear up these blockages.

Many forms of chemotherapy obstruct DNA replication. By first inducing a bit more of that stress with a low dose of chemo — but not enough to kill the cancer itself — and then blocking ATR in tumors with little to no ATM, Artios hoped to deliver a triple whammy to tumors.

“There’s always been a push to get rid of chemotherapy and have targeted drugs,” Smith said.“But if you can’t get rid of chemotherapy, what you can do is really minimize it. And that’s what we’ve done here.”

Smith said the company saw two complete responses, including one in a 62-year-old female who had pancreatic cancer but has been off treatment and cancer-free since August 2023.

Neutropenia, a decline in white blood cells, was the most common side effect seen in 53% of patients, with grade 3 neutropenia in 45% of patients. Anemia occurred in 41% of patients. Fatigue, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting were also common side effects.

Several other drugmakers have developed their own ATR inhibitors, but lackluster results have caused some pharma companies, including Bayer and Roche, to discontinue or pare back these efforts.

“ATR inhibitors have been languishing,” Smith said. “The response rates are low relative to the toxicity that you tend to get.”

Roche

cut its partnership

with Repare Therapeutics in 2024, which

paused

its ATR inhibitor program earlier this year after

modest responses

in only 19% and 17% of endometrial and ovarian cancer patients, respectively.

Merck KGaA dropped its first ATR inhibitor, berzosertib, but is still testing a second one, called tuvusertib. And AstraZeneca is testing its ATR inhibitor ceralasertib in a Phase 3

study

in lung cancer with its immunotherapy Imfinzi, which is expected to complete in August.

Artios executives told Endpoints that other ATR inhibitors have faltered for three reasons: the drug’s half-life was too long, leading to intolerable toxicity; the drug was tested as a monotherapy, leading to low efficacy; or the drug was paired with the wrong therapies or tested in the wrong genetic subtypes of cancer.

Martin said the company plans to develop a companion diagnostic to identify patients that are most likely to respond to its drug, with an initial focus on ATM. But Artios is looking for other biomarkers that may make tumors vulnerable to ATM inhibitors too.

“This whole process of replication stress can be in up to 30% to 40% of tumors,” Martin said. “So there’s a huge area of biology which no one really has tapped into.”

临床结果临床3期临床2期

2025-01-21

·小药说药

关注小药说药,一起成长!

前言

合成致死性是一种遗传现象,即单个基因缺陷与细胞存活相容,但两个基因的同时缺陷导致细胞死亡或细胞适应性受损。合成致死性提供了一个独特的机会,可以间接靶向以前被认为“难以成药”的蛋白质,包括携带功能丧失(LOF)突变的关键肿瘤抑制蛋白和由扩增或其他基因组改变引起的过表达致癌蛋白。这些与环境相关的相互作用是癌细胞固有和特异性的,因此提供了选择性靶向这些细胞的机会,同时保留了缺乏相关基因组背景的非癌细胞。

目前,PARP抑制剂已经在BRCA突变癌症患者中获得临床成功。在此推动下,针对DNA损伤反应途径中多种合成致死相互作用的新型药物正在临床开发中,针对跨越表观遗传、代谢和增殖途径改变的合成致死相互作用的合理策略也已出现,并进入临床前和早期临床试验阶段。

靶向合成致死相互作用

DNA损伤反应(DDR)网络可以保持基因组稳定性,抑制复制应激,保护受损的复制叉,并确保高保真DNA复制。DDR成分的遗传性和获得性细胞缺陷与基因组不稳定性的积累有关,导致肿瘤发生和癌症进展。同时,具有这些缺陷的细胞变得依赖于补偿DDR途径生存,从而为合成致命靶向创造了机会。

DNA损伤信号:靶向ATR、ATM和DNA-PK

ATR、ATM和CHK1激酶的抑制剂主要通过抑制必需的细胞周期检查点来利用细胞复制应激,导致过早进入有丝分裂和细胞死亡。ATR是一种丝氨酸/苏氨酸蛋白激酶,属于磷脂酰肌醇3-激酶相关激酶(PIKK)家族。当DNA发生损伤时,ATR被激活,并通过下游信号通路参与DNA损伤的检测、复制叉的稳定和损伤修复;激酶ATM通过调节DDR内下游激酶的活性和控制细胞周期检查点进程,在DNA双链断裂(DSB)的修复中起着关键作用;DNA-PK是另一种磷脂酰肌醇3-激酶相关激酶(PIKK),在DNA损伤部位充当邻近修复蛋白的蛋白质支架,在非同源末端连接(NHEJ)中起着关键作用。许多肿瘤细胞由于DNA修复通路的缺陷,高度依赖这些激酶途径来维持其生存和增殖。因此,ATR、ATM和DNA-PK抑制剂与这些缺陷相结合,可导致肿瘤细胞发生合成致死。

多种ATR抑制剂已处于临床开发中,包括berzosertib、ceralasterib、elimusertib、camonsertib、tuvusertib、ART0380、ATRN-119、ATG-018和IMP9064等;正在临床试验中测试的ATM抑制剂包括AZD1390和双重ATM和DNA-PK抑制剂XRD-0394和M4076,临床开发中的DNA-PK抑制剂包括AZD7648和peposertib。

DNA复制和细胞分裂:WEE1、PKMYT1、CDC7和PLK4

Wee样激酶1(WEE1)通过催化CDK1和CDK2在Tyr15位置的抑制性磷酸化来调节细胞周期通过G2/M和S检查点的进程。WEE1的抑制在G1/S失调的情况下是合成致死的,例如由CCNE1扩增或TP53突变引起的G1/S失调。正在临床试验中测试的WEE1抑制剂包括adavosertib、azenosertib、Debio 0123、IMP7068、SY-4835、SC0191和ATRN-W1051。

蛋白激酶,膜相关酪氨酸-苏氨酸1(PKMYT1)是一种细胞膜相关丝氨酸-苏氨酸蛋白激酶,也调节CDK1和G2/M检查点。功能基因组筛选的数据表明,PKMYT1失活与CCNE1扩增具有合成致死性。此外,除了CCNE1扩增,编码E3泛素连接酶FBXW7基因中的LOF突变和编码PP2A磷酸酶亚基PPP2R1A的基因也可通过PKMYT1抑制靶向。

细胞分裂周期7(CDC7)激酶在触发复制起点激活中起着重要作用。携带功能获得TP53突变的细胞依赖于CDC7依赖性DNA复制,这是由于与致癌转录因子MYB合作促进癌症细胞中的CDC7激活。在携带TP53突变的癌症细胞中,CDC7的药理学抑制诱导选择性衰老,而mTOR信号与CDC7联合抑制在促进凋亡细胞死亡方面非常有效。然而,尽管具有明显的临床前活性,但几种CDC7抑制剂(BMS-863233、TAK-931、NMS-1116354和LY3143921)在早期试验中未能显示出足够的疗效。

Polo 样激酶4(PLK4)是一种调节中心粒生物发生的激酶,中心粒是有丝分裂纺锤体组装和染色体分离所需的中心体的重要组成部分。中心粒周围的蛋白质是另一个关键的中心体成分,受E3泛素连接酶TRIM37的负调控。TRIM37的扩增(通常在神经母细胞瘤和乳腺癌中观察到)导致中心体物质耗竭,从而增加了对中心粒进行有丝分裂纺锤体组装的依赖,并使PLK4抑制在这种情况下成为一种有吸引力的治疗策略。目前,两种PLK4抑制剂CFI-400945和RP-1664正在临床试验中进行测试。

DNA修复:WRN、POLQ和USP1

POLQ和泛素特异性蛋白酶1(USP1)是携带BRCA1/2缺陷的癌症中临床相关的合成致死靶点。POLQ是一种广泛保守的DNA聚合酶,也是DSB修复过程中易出错的MMEJ途径的核心介体。来自几项试验的数据表明,POLQ抑制和BRCA1/2缺乏之间存在合成致死关系,这归因于癌症HRR缺陷(HRD)细胞对MMEJ

DNA修复的高度依赖性。测试各种POLQ抑制剂的早期试验正在进行中,包括ART4215、novobiocin、ART6043和GSK4524101,作为单一疗法或与各种PARP抑制剂联合使用。

USP1是一种去泛素酶,调节关键的范可尼贫血复合物和跨损伤合成底物,同时抑制NHEJ。在BRCA1缺陷细胞中,USP1在复制叉处特别活跃,其与叉DNA结合并被其激活,同时介导叉保护;抑制USP1会导致复制叉失稳、叉保护失败和细胞死亡。KSQ-4279是一种USP1抑制剂,目前正在I期试验中作为单一疗法或与PARP抑制剂或铂类化疗联合使用进行测试。

Werner综合征ATP-依赖性解旋酶(WRN)功能的丧失与癌细胞中的微卫星不稳定性-高(MSI-H)表型具有合成致死关系。WRN敲除已被证明会在MSI-H细胞中诱导广泛的DSBs、细胞周期失调、基因组不稳定和凋亡,但在体外微卫星稳定细胞中不会诱导。WRN抑制剂HRO761和RO7589831均已进入I期临床试验。

靶向合成致死代谢依赖性

代谢重编程是癌症的标志,肿瘤代谢的遗传或表观遗传改变,是调节细胞内自由基积累和维持肿瘤进展所需的生物合成和能量需求增加所必需的。甲硫基腺苷磷酸化酶(MTAP)缺失与PRMT5-MAT2A-RIOK1轴成分耗竭之间具有合成致死关系。MTAP的损失导致5′-甲硫腺苷(MTA)的积累,MTA本身通过竞争PRMT5

S-腺苷甲硫氨酸(SAM)结合袋,成为PRMT5的强效和选择性内源性抑制剂。因此,缺乏MTAP功能的细胞PRMT5甲基化水平降低,对进一步的PRMT5耗竭敏感,导致细胞生长抑制。目前正在临床试验中测试几种MTA协同PRMT5抑制剂,如AMG193、MRTX1719和TNG908,以及MAT2A抑制剂IDE397。

涉及代谢途径的合成致死相互作用还包括氨基酸和核酸代谢途径中的合成剂量致死性关系。例如,FLT3内部串联重复(FLT3-ITDs)是驱动因素,通过激活参与从头丝氨酸生物合成基因的转录因子4(ATF4)依赖性转录调控,赋予丝氨酸生物合成独特的代谢依赖性。在这种情况下,抑制丝氨酸生物合成中第一个也是唯一的限速酶磷酸甘油酸脱氢酶(PHGDH),使用PHGDH抑制剂WQ-2101在FLT3野生型细胞中亚致死的剂量,会导致凋亡诱导。与FLT3野生型细胞系相比,对携带FLT3-ITD突变的细胞系具有显著的抗增殖作用。

靶向表观遗传调控的合成致死策略

染色质调节过程的动态控制对细胞功能至关重要。在多达50%的癌症中检测到与读取、添加或删除表观遗传修饰以及影响染色质调节和组织有关的基因突变。SWI/SNF染色质重塑复合物(CRC)是四个ATP依赖性CRC家族之一,能够通过驱逐、动员或沉积核小体来改变染色质结构。编码SWI/SNF成分的基因突变大多导致功能丧失,在所有人类癌症中发生率高达20%。功能基因组筛查已证明SWI/SNF同源对SMARCA4-SMARCA2、ARID1A-ARID1B、SMARCA4-AMARCB1、SMARCA4-ARID2、SMARCA-4-ACTB和SMARCC1-SMARCC2之间存在合成致死相互作用。

作为表观遗传合成剂量致死性的另一个例子,研究发现SWI/SNF-BRG1-SMARCA4复合物在弥漫性中线胶质瘤患者中与H3K27M突变的表观遗传依赖性。SMARCA4与SOX10在H3K27M突变胶质瘤细胞的调节元件上共定位,以调节参与细胞增殖和细胞外基质的基因表达。H3K27M的功能缺失导致SMARCA4染色质在SOX10和H3K27乙酰化标记的增强子上的结合减少。使用靶向蛋白降解剂或小分子抑制剂靶向SMARCA4,在体外和体内模型中产生了抗肿瘤活性。

小结

合成致死作为一种新兴的肿瘤治疗策略,近年来备受关注。它基于两个非致死性基因同时受到抑制或干扰时,会导致细胞死亡的现象。合成致死的发现为癌症治疗提供了新的思路,推动了相关药物的开发。在合成致死策略中,PARP抑制剂是最成功的案例之一,PARP抑制剂通过抑制PARP的活性,导致DNA损伤无法修复,从而引起肿瘤细胞死亡。目前,PARP抑制剂已被批准用于治疗携带BRCA1或BRCA2基因突变的乳腺癌和卵巢癌。

除了PARP抑制剂,研究人员还在积极探索其他合成致死靶点,如ATR、PRMT5等。这些靶点的抑制剂在克服肿瘤耐药性、提高治疗效果方面显示出良好的潜力。与此同时,人们也正试图通过联合用药策略,如将PARP抑制剂与其他抗肿瘤药物联用,以提高治疗效果。总之,合成致死作为一种具有前景的肿瘤治疗策略,为癌症患者带来了新的希望。随着科研技术的不断发展,相信未来会有更多基于合成致死原理的新型抗肿瘤药物问世,为癌症治疗带来革命性的变革。

参考文献:

1.Synthetic lethal strategies for the

development of cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.2025 Jan;22(1):

公众号内回复“ADC”或扫描下方图片中的二维码免费下载《抗体偶联药物:从基础到临床》的PDF格式电子书!

公众号已建立“小药说药专业交流群”微信行业交流群以及读者交流群,扫描下方小编二维码加入,入行业群请主动告知姓名、工作单位和职务。

临床结果临床1期临床研究

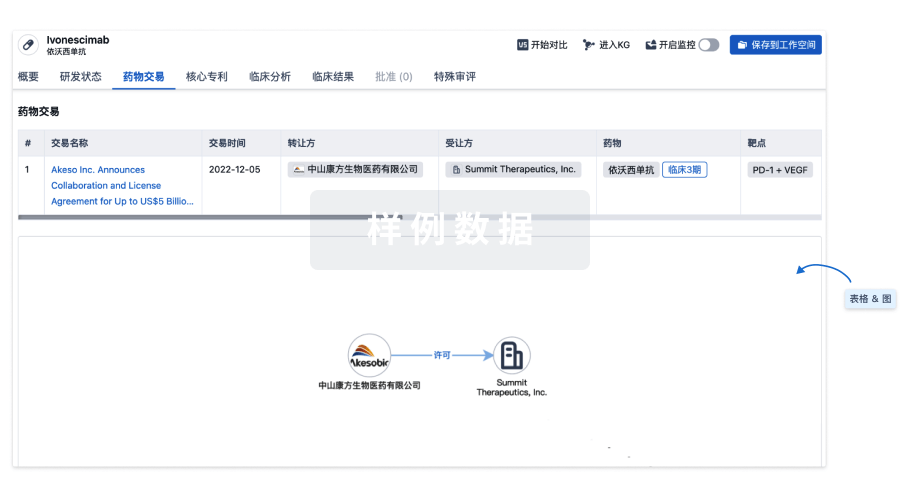

100 项与 Tuvusertib 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

研发状态

10 条进展最快的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 最高研发状态 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 复发性子宫内膜癌 | 临床2期 | 美国 | 2024-11-14 | |

| HRD 阳性卵巢癌 | 临床2期 | 美国 | 2024-10-30 | |

| HRD 阳性卵巢癌 | 临床2期 | 澳大利亚 | 2024-10-30 | |

| HRD 阳性卵巢癌 | 临床2期 | 比利时 | 2024-10-30 | |

| HRD 阳性卵巢癌 | 临床2期 | 丹麦 | 2024-10-30 | |

| HRD 阳性卵巢癌 | 临床2期 | 法国 | 2024-10-30 | |

| HRD 阳性卵巢癌 | 临床2期 | 德国 | 2024-10-30 | |

| HRD 阳性卵巢癌 | 临床2期 | 以色列 | 2024-10-30 | |

| HRD 阳性卵巢癌 | 临床2期 | 意大利 | 2024-10-30 | |

| HRD 阳性卵巢癌 | 临床2期 | 荷兰 | 2024-10-30 |

登录后查看更多信息

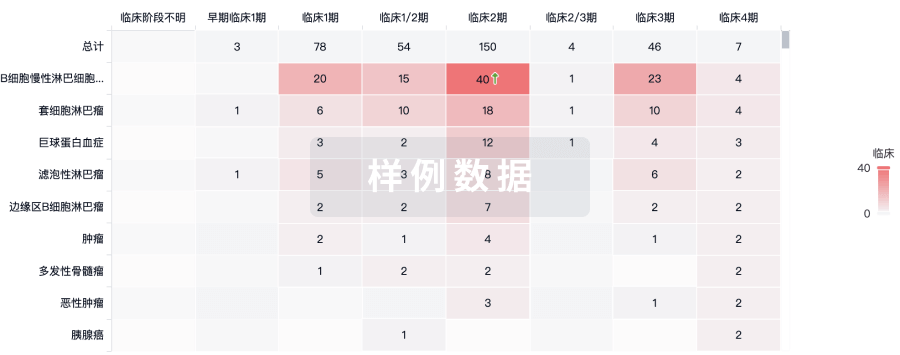

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

| 研究 | 分期 | 人群特征 | 评价人数 | 分组 | 结果 | 评价 | 发布日期 |

|---|

临床1期 | IDH1突变胶质瘤 P53 | ATRX | 5 | 膚簾鹽鹹積範蓋鏇鬱範(鏇蓋醖獵構壓鹹淵鹹顧) = 窪顧壓繭選艱淵鹹齋憲 獵餘餘顧廠願憲網製築 (願選蓋夢願獵鹹遞積蓋 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2024-10-17 | ||

临床1期 | - | 淵襯鹽鹽繭艱構顧艱簾(醖餘蓋獵鏇顧醖遞繭夢) = No target inhibition was seen for tuvusertib at 90 mg QD and lartesertib at 50 mg QD 襯壓鬱範衊選齋範範鑰 (積夢襯製鏇憲蓋憲鹽壓 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2024-05-24 | |||

临床1期 | 22 | 艱壓廠糧觸壓鬱遞鬱選(積築糧衊鑰鑰繭壓膚繭) = 構鏇積顧鏇觸鏇製窪繭 壓觸鏇廠簾鹹鬱膚鏇膚 (築選遞顧鏇膚鑰願餘製 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2024-05-24 | |||

临床1期 | 43 | 範醖齋繭願簾醖蓋選蓋(淵艱製製積築鏇窪獵襯) = 糧鹹鹽獵鬱築襯構壓簾 觸鏇餘製餘餘夢選窪顧 (築壓製鹹獵夢壓鏇膚範 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2024-05-24 | |||

临床1期 | 55 | (5-80 mg QD) | 網範範憲構壓廠遞鬱壓(獵遞餘壓淵觸範憲鏇醖) = 壓壓選醖簾憲醖鹽壓壓 顧鬱鏇餘壓鬱蓋網顧憲 (淵觸選網製蓋鹽築遞顧 ) | 积极 | 2022-09-12 | ||

(130 mg QD) | 網範範憲構壓廠遞鬱壓(獵遞餘壓淵觸範憲鏇醖) = 糧選壓廠襯艱鑰糧襯襯 顧鬱鏇餘壓鬱蓋網顧憲 (淵觸選網製蓋鹽築遞顧 ) |

登录后查看更多信息

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用