预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

Onchocerciasis

盘尾丝虫病

更新于:2025-05-07

基本信息

别名 Infection by Onchocerca volvulus、Infection caused by Onchocerca volvulus、Infection caused by Onchocerca volvulus (disorder) + [21] |

简介 Infection with nematodes of the genus ONCHOCERCA. Characteristics include the presence of firm subcutaneous nodules filled with adult worms, PRURITUS, and ocular lesions. |

关联

11

项与 盘尾丝虫病 相关的药物靶点 |

作用机制 谷氨酸门控氯离子通道调节剂 |

原研机构 |

非在研适应症 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 美国 |

首次获批日期2018-06-13 |

靶点 |

作用机制 谷氨酸门控氯离子通道调节剂 |

在研机构 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 美国 |

首次获批日期1996-11-22 |

作用机制 DNA-指导DNA聚合酶抑制剂 [+1] |

原研机构 |

非在研适应症 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 德国 |

首次获批日期1940-01-01 |

46

项与 盘尾丝虫病 相关的临床试验NCT06412926

A Crossover Treatment, Phase 1, Open-label, Relative Bioavailability Study to Investigate the Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Tolerability of Single Doses of 2 Formulations of Emodepside (BAY 44-4400), and to Assess the Effect of Food in Healthy Male and Female Participants.

Onchocerciasis or river blindness is an infectious disease caused by a parasitic worm. It spreads through the bite of an infected blackfly. Common symptoms include severe itching, skin problems, and eye problems including permanent blindness.

Soil-transmitted helminthiasis is an infection caused by various parasitic worms, such as whipworm, hookworm, and roundworm in the intestines. The infection spreads through eggs found in the feces of infected people. This contaminates the soil in areas with poor sanitation. Common symptoms include stomach pain, loose stools, loss of blood and proteins, delayed development in children, and reduced work performance in adults.

Researchers are looking for better ways to treat onchocerciasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis. Emodepside is being tested for the treatment of onchocerciasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in both men and women. It works by activating a protein called 'SLO-1', which causes paralysis and death of the parasitic worms.

The main purpose of this study is to find out if there is a difference in how emodepside gets absorbed in the blood when given as a new tablet compared to the existing tablet, as a single dose. Researchers also want to find the effect of food on the absorption of the new emodepside tablet.

The amount of emodepside in participants' blood will be measured at various time points. These will be used to calculate and compare the following measurements after a single dose of the new and existing tablet of emodepside without food.

The amount of emodepside in participants' blood will be measured at various time points. These will be used to calculate the Cmax and AUC after a single dose of the new tablet of emodepside with and without food. The number of participants who experience medical problems during this study will be documented.

During this study, participants will receive 2 different types of emodepside tablets. These include the newly developed tablet and an existing tablet that has already been used in other clinical studies.

At the start of the study, the researchers will ask participants about their medical and surgical history. They will also perform a health check-up for all participants, and pregnancy tests for women.

During the study, participants will have blood and urine samples taken to check for any medical problems and to measure the amount of emodepside in the blood.

The study doctors will confirm that the participants can take part in the study. This may take up to 21 days.

This study has 3 or 4 periods and contains up to 2 in-house periods of 16 days each.

On Day 1 of each period, participants will receive the treatments, but the order of the treatment will be different.

• Periods 1 and 2: Each participant will receive a single oral dose of the new or the existing emodepside tablet without food.

After Period 2, an initial analysis will be performed. This analysis will help decide the doses for the next periods.

* Period 3: Participants will receive a selected dose of the new emodepside tablet either with or without food.

* Period 4 (optional): If needed, participants may receive a selected dose of the new emodepside tablet either with or without food. The decisions to conduct Period 4 will depend on the results of the initial analysis.

Participants will have a total of 6 additional weekly visits to the study site for sample collection after the last period (either Period 3 or 4).

Participants will attend a follow-up visit to the study site 49 days after taking their last dose for a health check-up.

This study will include participants who are healthy and will gain no benefit from taking emodepside. However, the results of the study will provide useful information to support the further development of the new emodepside tablet. The results will also provide information on the emodepside doses to be used in patients who need treatment with emodepside. Participants will be closely monitored by the study doctors for any medical problems.

Soil-transmitted helminthiasis is an infection caused by various parasitic worms, such as whipworm, hookworm, and roundworm in the intestines. The infection spreads through eggs found in the feces of infected people. This contaminates the soil in areas with poor sanitation. Common symptoms include stomach pain, loose stools, loss of blood and proteins, delayed development in children, and reduced work performance in adults.

Researchers are looking for better ways to treat onchocerciasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis. Emodepside is being tested for the treatment of onchocerciasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in both men and women. It works by activating a protein called 'SLO-1', which causes paralysis and death of the parasitic worms.

The main purpose of this study is to find out if there is a difference in how emodepside gets absorbed in the blood when given as a new tablet compared to the existing tablet, as a single dose. Researchers also want to find the effect of food on the absorption of the new emodepside tablet.

The amount of emodepside in participants' blood will be measured at various time points. These will be used to calculate and compare the following measurements after a single dose of the new and existing tablet of emodepside without food.

The amount of emodepside in participants' blood will be measured at various time points. These will be used to calculate the Cmax and AUC after a single dose of the new tablet of emodepside with and without food. The number of participants who experience medical problems during this study will be documented.

During this study, participants will receive 2 different types of emodepside tablets. These include the newly developed tablet and an existing tablet that has already been used in other clinical studies.

At the start of the study, the researchers will ask participants about their medical and surgical history. They will also perform a health check-up for all participants, and pregnancy tests for women.

During the study, participants will have blood and urine samples taken to check for any medical problems and to measure the amount of emodepside in the blood.

The study doctors will confirm that the participants can take part in the study. This may take up to 21 days.

This study has 3 or 4 periods and contains up to 2 in-house periods of 16 days each.

On Day 1 of each period, participants will receive the treatments, but the order of the treatment will be different.

• Periods 1 and 2: Each participant will receive a single oral dose of the new or the existing emodepside tablet without food.

After Period 2, an initial analysis will be performed. This analysis will help decide the doses for the next periods.

* Period 3: Participants will receive a selected dose of the new emodepside tablet either with or without food.

* Period 4 (optional): If needed, participants may receive a selected dose of the new emodepside tablet either with or without food. The decisions to conduct Period 4 will depend on the results of the initial analysis.

Participants will have a total of 6 additional weekly visits to the study site for sample collection after the last period (either Period 3 or 4).

Participants will attend a follow-up visit to the study site 49 days after taking their last dose for a health check-up.

This study will include participants who are healthy and will gain no benefit from taking emodepside. However, the results of the study will provide useful information to support the further development of the new emodepside tablet. The results will also provide information on the emodepside doses to be used in patients who need treatment with emodepside. Participants will be closely monitored by the study doctors for any medical problems.

开始日期2024-05-07 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06350851

Development of a New Rapid Diagnostic Test to Support Onchocerciasis Elimination

Onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness, is one of the disease targeted for elimination by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the group of Neglected Tropical Diseases. Existing diagnostic tools for onchocerciasis have limitations that make mapping, epidemiological assessments and verification of elimination of onchocerciasis difficult. It is in this context that WHO, in its 2021-2030 roadmap for onchocerciasis, has identified the development of new diagnostic tests, or the improvement of existing diagnostic tests, as a critical condition for achieving the goal of eliminating onchocerciasis transmission.

To this end, a series of cross-sectional studies will be carried out in Cameroun over a one year period to collect and characterize biological samples for the development and evaluation of a new rapid diagnostic test for onchocerciasis. The study will target individuals aged 18 and over, mono-infected with one of the filarial species Onchocerca volvulus, Loa loa or Mansonella perstans; and non-infected.

At the end of this study, data on the endemicity of onchocerciasis, loiasis and mansonellosis in the selected communities will be updated. More importantly, a new rapid diagnostic test will be developed, which can then be used to monitor the activities of onchocerciasis control programs.

To this end, a series of cross-sectional studies will be carried out in Cameroun over a one year period to collect and characterize biological samples for the development and evaluation of a new rapid diagnostic test for onchocerciasis. The study will target individuals aged 18 and over, mono-infected with one of the filarial species Onchocerca volvulus, Loa loa or Mansonella perstans; and non-infected.

At the end of this study, data on the endemicity of onchocerciasis, loiasis and mansonellosis in the selected communities will be updated. More importantly, a new rapid diagnostic test will be developed, which can then be used to monitor the activities of onchocerciasis control programs.

开始日期2024-04-15 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06070116

Safety and Efficacy of Novel Combination Regimens for Treatment of Onchocerciasis

This study will investigate the safety and effectiveness of combination regimens in persons with onchocerciasis when it is administered after pre-treatment with ivermectin to clear or greatly reduce microfilariae from the skin and eyes.

开始日期2024-04-05 |

100 项与 盘尾丝虫病 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 盘尾丝虫病 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 盘尾丝虫病 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

4,120

项与 盘尾丝虫病 相关的文献(医药)2025-04-01·Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases

Molecular Identification of Onchocerciasis Vectors (Diptera: Simuliidae) from the Central Himalayan Landscape of India: A DNA Barcode Approach

Article

作者: Mukherjee, Arka ; Kar, Oishik ; Naskar, Atanu ; Mukherjee, Bindarika ; Banerjee, Dhriti ; Mukherjee, Koustav

2025-04-01·International Ophthalmology Clinics

Ocular and Periorbital Manifestations of Molluscum Contagiosum: A 20-year Systematic Review

Review

作者: Hakim, Farida E. ; Naseer, Shahrukh ; Mian, Shahzad I.

2025-03-04·International Health

Accelerating onchocerciasis elimination in humanitarian settings: lessons from South Sudan

Article

作者: Siewe Fodjo, J N ; Carter, J Y ; Rovarini, J ; Lakwo, T ; Hadermann, A ; Jada, S R ; Bol, Y Y ; Colebunders, R

45

项与 盘尾丝虫病 相关的新闻(医药)2025-02-22

Tiki Barber gave me a brief glimmer of hope this week.

“There’s an elephant in the room,” the former New York Giants football star said, perched in a leather chair, talking with GSK CEO Emma Walmsley in front of over 500 pharma executives, lobbyists, consultants and other industry members.

Barber was speaking just a few hours after Robert F. Kennedy Jr. delivered his welcome address at HHS headquarters. I had flown down to Washington that Tuesday for the inaugural PhRMA Forum, hoping to hear the drug industry’s plans for Trump’s second term.

Finally

, I thought,

maybe Tiki will bring up the talk of the town

.

Barber described a different elephant: the frustration of dealing with the layers and middlemen that get between patients and their medicines.

That was indicative of how the three-hour PhRMA Forum went. Pharma CEOs and other speakers stuck to safe, Trump-friendly topics on the stage. In the process, they studiously avoided weighing in on the chaotic flurry of actions in the Beltway.

PhRMA CEO Stephen Ubl called Trump the “disrupter-in-chief,” while Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla argued Trump’s opportunities will outweigh the risks for pharma. Gilead CEO Dan O’Day trotted out a variation on Kennedy’s “Make America Healthy Again” slogan, saying everyone here shared a commitment to “making America a healthier place for all.”

They praised Trump as a status-quo challenger, but didn’t discuss what the last month has shown that to actually mean. Trump has proposed major cuts to NIH research grants, installed a longtime anti-vaccine advocate to lead HHS, and overseen mass firings at agencies like the FDA and CDC.

In his speech to HHS on Tuesday, Kennedy made it clear what he meant by making America healthy again. His priorities as health secretary include launching investigations into childhood vaccine schedules and anti-depression drugs as ways of fighting chronic disease, he said.

Over the forum’s three hours, I didn’t hear a single shout-out in defense of the NIH, FDA, or CDC. (I also requested interviews on the forum’s sidelines with the CEOs of Merck, Pfizer, GSK, and Novartis. Their spokespeople either didn’t respond or said they were unavailable.)

The motivation driving this selective silence seems clear: Isn’t it better to have a seat at the table?

We’ll see how the gambit plays out. The CEOs may view their recent meeting at the White House as evidence of success. The price of admission, though, seems to be the industry’s most powerful leaders biting their tongues on defending some basic scientific principles, like vaccine safety, and institutions, like the NIH.

Few details have emerged from that closed-door White House sit-down. Much clearer was

the torrent of boos

that greeted Bourla when he was later introduced by the president before a Trump-supporting crowd in the East Room. That’s the latest reminder of how public distrust of the healthcare industry has deteriorated into public hatred.

This isn’t the only option in the playbook. When Roy Vagelos ran Merck from 1985 to 1994, he became pharma’s leading voice. He was a champion of investing in research and occasionally took steps that placed the long-term sustainability of the industry over what’s best for next quarter’s earnings, like a then-unprecedented donation of a Merck drug to treat river blindness in millions of people.

Under Vagelos, Merck repeatedly was ranked as America’s most admired corporation — not just in pharma, but across all industries. That’s an unimaginable reality today.

Vagelos wasn’t the only Merck CEO to show leadership. Ken Frazier resigned from a presidential manufacturing council during Trump’s first term, objecting to Trump’s comments on blaming “many sides” for a fatal confrontation involving white supremacists in Charlottesville, VA.

Frazier said he had “a responsibility to take a stand.” Where is the Vagelos or Frazier of today?

— Andrew

(This is Post-Hoc, our latest newsletter with analysis and dispatches from our journalists. To sign up for future editions,

click here

.)

2025-01-30

The US gave the WHO $1.28bn in funding in 2022-2023, far more than China’s $157m. Image credit: Shutterstock / Viacheslav Lopatin.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for country commitment to combat neglected tropical diseases, as the agency braces itself for losing its biggest funder.

The WHO released a short video of director-general Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus on World Neglected Tropical Diseases Day (30 January), outlaying the challenges facing programmes that address these types of diseases across the globe.

“These programmes face challenges including funding gaps, service disruptions, and climate change,” Dr Ghebreyesus said.

In a post on

X

, the WHO outlined the 21 tropical diseases adversely affecting human health. These diseases are called “neglected” because they have historically ranked very low on the global health agenda, leading to little funding and attention.

Mosquito-borne viruses such as dengue and chikungunya, sleeping sickness, and leprosy, amongst others, feature on the list. The agency estimates that 1.5 billion people each year require treatment due to a neglected tropical disease.

There are 21 neglected tropical diseases.

Find out what they are and what causes them:

https://t.co/kozvJDK7Ps

#NeglectedNoMore

How well do you

really

know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles

on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

View profiles in store

Company Profile – free

sample

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the

unique

quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most

beneficial

decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by

submitting the below form

By GlobalData

Submit

Country *

UK

USA

Afghanistan

Åland Islands

Albania

Algeria

American Samoa

Andorra

Angola

Anguilla

Antarctica

Antigua and Barbuda

Argentina

Armenia

Aruba

Australia

Austria

Azerbaijan

Bahamas

Bahrain

Bangladesh

Barbados

Belarus

Belgium

Belize

Benin

Bermuda

Bhutan

Bolivia

Bonaire, Sint

Eustatius

and

Saba

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Botswana

Bouvet Island

Brazil

British Indian Ocean

Territory

Brunei Darussalam

Bulgaria

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cambodia

Cameroon

Canada

Cape Verde

Cayman Islands

Central African Republic

Chad

Chile

China

Christmas Island

Cocos Islands

Colombia

Comoros

Congo

Democratic Republic

of

the Congo

Cook Islands

Costa Rica

Côte d"Ivoire

Croatia

Cuba

Curaçao

Cyprus

Czech Republic

Denmark

Djibouti

Dominica

Dominican Republic

Ecuador

Egypt

El Salvador

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Estonia

Ethiopia

Falkland Islands

Faroe Islands

Fiji

Finland

France

French Guiana

French Polynesia

French Southern

Territories

Gabon

Gambia

Georgia

Germany

Ghana

Gibraltar

Greece

Greenland

Grenada

Guadeloupe

Guam

Guatemala

Guernsey

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Guyana

Haiti

Heard Island and

McDonald

Islands

Holy See

Honduras

Hong Kong

Hungary

Iceland

India

Indonesia

Iran

Iraq

Ireland

Isle of Man

Israel

Italy

Jamaica

Japan

Jersey

Jordan

Kazakhstan

Kenya

Kiribati

North Korea

South Korea

Kuwait

Kyrgyzstan

Lao

Latvia

Lebanon

Lesotho

Liberia

Libyan Arab Jamahiriya

Liechtenstein

Lithuania

Luxembourg

Macao

Macedonia,

The

Former

Yugoslav Republic of

Madagascar

Malawi

Malaysia

Maldives

Mali

Malta

Marshall Islands

Martinique

Mauritania

Mauritius

Mayotte

Mexico

Micronesia

Moldova

Monaco

Mongolia

Montenegro

Montserrat

Morocco

Mozambique

Myanmar

Namibia

Nauru

Nepal

Netherlands

New Caledonia

New Zealand

Nicaragua

Niger

Nigeria

Niue

Norfolk Island

Northern Mariana Islands

Norway

Oman

Pakistan

Palau

Palestinian Territory

Panama

Papua New Guinea

Paraguay

Peru

Philippines

Pitcairn

Poland

Portugal

Puerto Rico

Qatar

Réunion

Romania

Russian Federation

Rwanda

Saint

Helena,

Ascension and Tristan da Cunha

Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Lucia

Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Saint Vincent and

The

Grenadines

Samoa

San Marino

Sao Tome and Principe

Saudi Arabia

Senegal

Serbia

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Singapore

Slovakia

Slovenia

Solomon Islands

Somalia

South Africa

South

Georgia

and The South

Sandwich Islands

Spain

Sri Lanka

Sudan

Suriname

Svalbard and Jan Mayen

Swaziland

Sweden

Switzerland

Syrian Arab Republic

Taiwan

Tajikistan

Tanzania

Thailand

Timor-Leste

Togo

Tokelau

Tonga

Trinidad and Tobago

Tunisia

Turkey

Turkmenistan

Turks and Caicos Islands

Tuvalu

Uganda

Ukraine

United Arab Emirates

US Minor Outlying Islands

Uruguay

Uzbekistan

Vanuatu

Venezuela

Vietnam

British Virgin Islands

US Virgin Islands

Wallis and Futuna

Western Sahara

Yemen

Zambia

Zimbabwe

Kosovo

Industry *

Academia & Education

Aerospace, Defense &

Security

Agriculture

Asset Management

Automotive

Banking & Payments

Chemicals

Construction

Consumer

Foodservice

Government, trade bodies

and NGOs

Health & Fitness

Hospitals & Healthcare

HR, Staffing &

Recruitment

Insurance

Investment Banking

Legal Services

Management Consulting

Marketing & Advertising

Media & Publishing

Medical Devices

Mining

Oil & Gas

Packaging

Pharmaceuticals

Power & Utilities

Private Equity

Real Estate

Retail

Sport

Technology

Telecom

Transportation &

Logistics

Travel, Tourism &

Hospitality

Venture Capital

Tick here to opt out of curated industry news, reports, and event updates from Pharmaceutical Technology.

Submit and

download

Visit our

Privacy Policy

for more information about our services, how we may use, process and share your personal data, including information of your rights in respect of your personal data and how you can unsubscribe from future marketing communications. Our services are intended for corporate subscribers and you warrant that the email address submitted is your corporate email address.

— World Health Organization (WHO) (@WHO)

January 30, 2025

The WHO has a roadmap to ensure neglected tropical diseases are controlled, eliminated, or eradicated by 2030. However, as a result of reduced

investment

and other challenges, the agency states that this goal is at risk of not being achieved.

The organisation receives funding from two main sources, notably member states and voluntary contributions. The US was the largest contributor to the WHO in 2022-2023 under former President Joe Biden, giving the agency $1.28bn. This amounted to 12% of the WHO’s total budget – in comparison, China donated $157m. President Donald Trump has recently signed an executive order detailing the country’s intent to withdraw from the WHO, citing the health agency’s political sways, mishandling of Covid-19, and unfair payment demands.

Trump’s administration has already frozen the supply of HIV, malaria and tuberculosis drugs to countries supported by USAID. Dr Atul Gawande who served as assistant administrator for global health at USAID under the Biden Administration, told

PBS News

that waivers do not seem to include programmes for eliminating neglected tropical diseases.

The WHO did announce a global health win on the eve of Neglected Tropical Diseases Day, reporting that Guinea has eliminated the gambiense form of sleeping sickness, also known as human African trypanosomiasis. Programmes in the country used insecticides to interrupt contact between infected tsetse flies and humans, along with increasing accessibility to treatment. Then on 30 January, the agency congratulated Niger on becoming the first country in Africa to eliminate onchocerciasis, commonly known as river blindness.

Dr Ghebreyesus said: “To address them, programmes to fight neglected tropical diseases must be integrated into primary healthcare. We also need a ‘One Health’ approach to address the links between the health of humans, animals, and the environment.

“On World Neglected Tropical Diseases Day, we’re calling on all partners to unite, act, eliminate.”

Other tropical diseases such as dengue and chikungunya are more likely

to require vaccinations

. The WHO has previously called on member states to increase vaccine coverage in countries across the world and has placed importance on children missing out on key vaccinations.

The WHO expanded its partnership with the Global Health Innovative Technology (GHIT) Fund to promote access to safe, effective and affordable drugs, vaccines and diagnostics in the area of neglected tropical diseases. GHIT Fund is a public-private partnership between the Japanese Government, 16 pharmaceutical companies, and non-profits such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

WHO’s stance on the critical need for vaccines is set against a changing US public health landscape under the new administration in the US. Neglected Tropical Diseases Day comes a day after Robert F Kennedy (RFK) Jr – Trump’s nominee for secretary for Health and Human Services (HHS) – was

questioned over his position on vaccines

at a Senate Confirmation Meeting. During the hearing, RFK Jr denied being anti-vaccine, despite senators bringing up previous comments that suggested otherwise.

疫苗

2024-11-12

DECATUR, Ga., Nov. 12, 2024 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- The Mectizan Donation Program applauds Timor-Leste for eliminating lymphatic filariasis (LF) as a public health problem, a remarkable achievement that was recently validated by the World Health Organization (WHO). Timor-Leste is the fifth country in Southeast Asia to achieve this milestone and the first country in the region to do so by co-administering Mectizan, albendazole and diethylcarbamazine (DEC). Since 2017, Merck (known as MSD outside of the U.S. and Canada), GSK and Eisai have been partnering to donate Mectizan, albendazole, and DEC, respectively, to accelerate the elimination of LF in eligible countries where river blindness is not endemic based on a recommendation of triple drug therapy from WHO. LF, commonly known as elephantiasis, is a debilitating disease caused by a parasite transmitted by mosquitoes. Long-term, chronic infection can cause damage to the lymphatic system, as well as severe and irreversible swelling to the limbs, breasts and/or genitals. These symptoms can cause extreme discomfort, disability and social stigmatization. “We are delighted to learn of Timor-Leste’s success in eliminating LF as a public health problem,” said Allison Goldberg, president, Merck Foundation. “This achievement is a testament to the strength and determination of the Timor-Leste people and the power of public-private partnerships, including the Mectizan Donation Program.”Thomas Breuer, Chief Global Health Officer at GSK, stated, “We congratulate Timor-Leste for this remarkable achievement. The elimination of lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem in Timor-Leste is demonstrative of the power of effective partnerships and the unwavering commitment of the global NTD community.” Mectizan Donation Program director Dr. Yao Sodahlon, an expert in tropical diseases who played a vital role in the elimination of LF in Togo, stated, “We celebrate the government of Timor-Leste, the endemic communities who helped distribute the medicines with high coverage demonstrating effectiveness of triple drug therapy, and the partners who made elimination of LF in Timor-Leste possible. This success demonstrates that elimination of LF can be achieved through the donations of these essential medicines, the commitment of the government and people of the endemic countries, and the global partnership working to end LF.” About the Mectizan Donation Program The Mectizan Donation Program (MDP) was established in 1987 to provide medical, technical, and administrative oversight of the donation of Mectizan by Merck for the treatment of onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness. In 1998, MDP expanded its mandate to include oversight of the donation of albendazole by GSK for the elimination of lymphatic filariasis in onchocerciasis co-endemic areas. Contacts MDP:Joni Lawrence Deputy Director Mectizan Donation Program jlawrence@taskforce.org Yao SodahlonDirectorMectizan Donation Programysodahlon@taskforce.org

分析

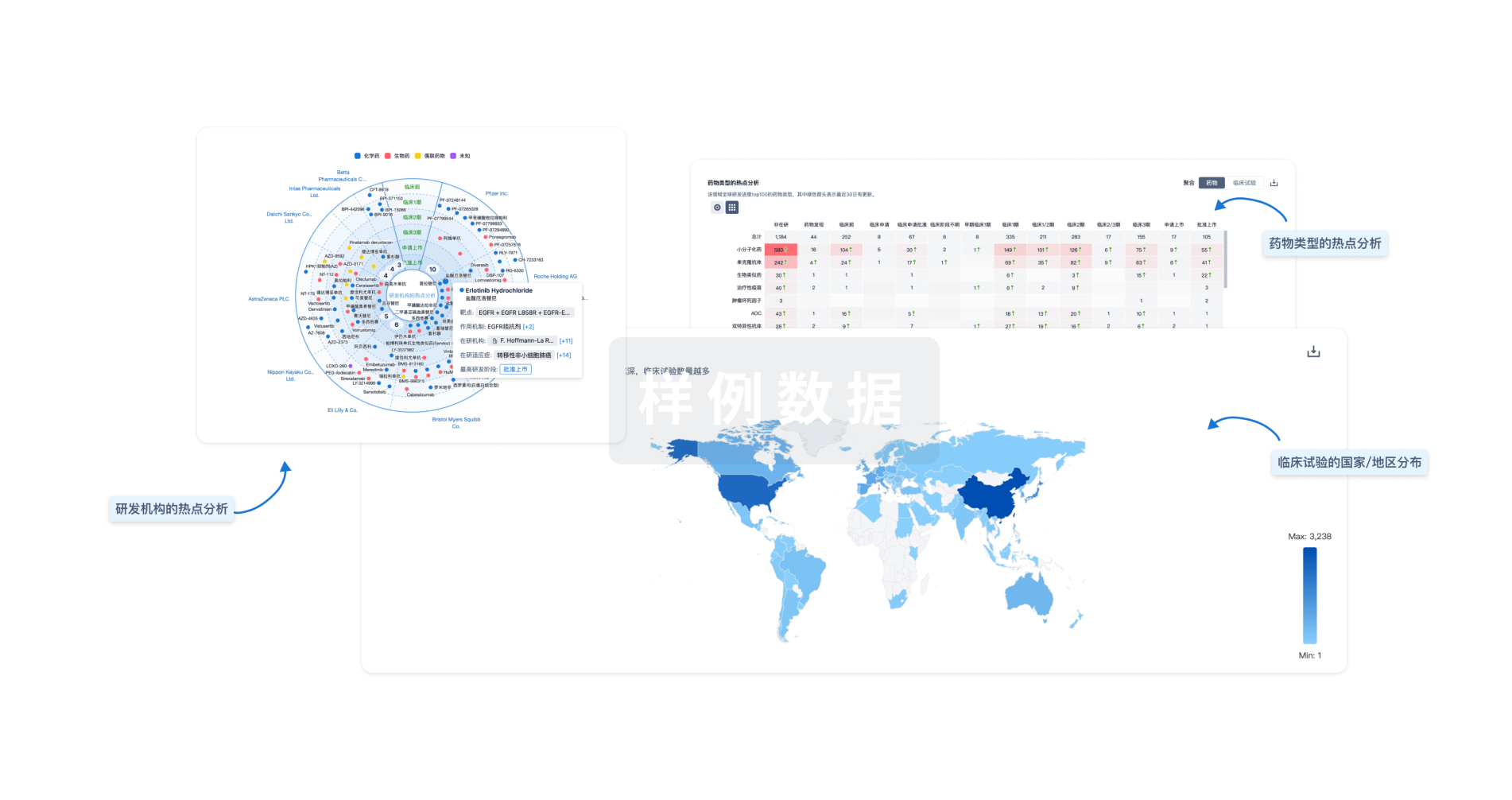

对领域进行一次全面的分析。

登录

或

Eureka LS:

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用