预约演示

更新于:2025-08-27

WuXi Biologics (Cayman), Inc.

更新于:2025-08-27

概览

标签

感染

单克隆抗体

疾病领域得分

一眼洞穿机构专注的疾病领域

暂无数据

技术平台

公司药物应用最多的技术

暂无数据

靶点

公司最常开发的靶点

暂无数据

| 排名前五的药物类型 | 数量 |

|---|---|

| 单克隆抗体 | 6 |

| 抗体 | 1 |

| 双特异性抗体 | 1 |

关联

8

项与 药明生物技术有限公司 相关的药物作用机制 SARS-CoV-2 S protein抑制剂 |

在研机构 |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

WO2023164872

专利挖掘靶点 |

作用机制- |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段药物发现 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

WO2024098180

专利挖掘靶点 |

作用机制- |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段药物发现 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

100 项与 药明生物技术有限公司 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 药明生物技术有限公司 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

8

项与 药明生物技术有限公司 相关的文献(医药)2024-06-01·Journal of microbiological methods

A flexible ‘plug and play’ bicistronic construct and its application in the screening of protein expression system in Escherichia coli

Article

作者: Li, Zhaopeng ; Hu, Weiwei ; Duan, Yingyi ; Feng, Binbin

The bicistronic expression system that utilizes fluorescent reporters has been demonstrated to be a straightforward method for detecting recombinant protein expression levels, particularly when compared to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analysis, which are tedious and labor-intensive. However, existing bicistronic reporter systems are less capable of quantitative measurement due to the lag in reporter expression and its negative impact on target protein. In this work, a plug and play bicistronic construct using mCherry as reporter was applied in the screening of optimal replicon and promoter for Sortase expression in Escherichia coli (E. coli). The bicistronic construct allowed the reporter gene and target open reading frame (ORF) to be co-transcribed under the same promoter, resulting in a highly positive quantitative correlation between the expression titer of Sortase and the fluorescent intensity (R2 > 0.97). With the correlation model, the titer of target protein can be quantified by noninvasively measuring the fluorescent intensity. On top of this, the expression of reporter has no significant effect on the yield of target protein, thus favoring a plug and play design for removing reporter gene to generate a plain plasmid for industrial use.

2024-05-01·World journal of microbiology & biotechnology

Microbial chassis design and engineering for production of gamma-aminobutyric acid

Review

作者: Wang, Xiaoyuan ; Wang, Jianli ; Ma, Wenjian ; Zhao, Lei ; Zhou, Jingwen

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a non-protein amino acid which is widely applied in agriculture and pharmaceutical additive industries. GABA is synthesized from glutamate through irreversible α-decarboxylation by glutamate decarboxylase. Recently, microbial synthesis has become an inevitable trend to produce GABA due to its sustainable characteristics. Therefore, reasonable microbial platform design and metabolic engineering strategies for improving production of GABA are arousing a considerable attraction. The strategies concentrate on microbial platform optimization, fermentation process optimization, rational metabolic engineering as key metabolic pathway modification, promoter optimization, site-directed mutagenesis, modular transporter engineering, and dynamic switch systems application. In this review, the microbial producers for GABA were summarized, including lactic acid bacteria, Corynebacterium glutamicum, and Escherichia coli, as well as the efficient strategies for optimizing them to improve the production of GABA.

2024-02-01·Food chemistry

Deciphering the thick filaments assembly behavior of myosin as affected by enzymatic deamidation

Article

作者: Chen, Xing ; Zhang, Yanyun ; Zhou, Peng ; Fu, Wenyan ; Liu, Dongmei

Enzymatic deamidation is a promising approach in enhancing the solubility of myofibrillar proteins (MPs) in water paving the way of tailor manufacturing muscle protein-based beverages. This work aimed to clarify the solubilization mechanism by deciphering myosin thick filaments assembly as affected by protein-glutaminase deamidation. With the extension of deamidation, filamentous structures in MPs shortened continuously. Dynamic monitoring of quartz crystal microbalance-dissipated showed the adsorption capacity of the deaminated MPs was reduced from 3.66 ng/cm2 to 2.03 ng/cm2, indicating that the ability to assemble myosin thick filaments was significantly weakened. By simulating the surface charge, it was found that deamidation may neutralize the positive charged clusters distanced at 14-29 nm from rod C-terminus. Since this region confers myosin electrostatic property to initiate staggered dimerization, deamidation in this region, which severely affected the electrostatic balance between residues, impaired ordered thick filament growing and elongating, thus promoting the solubilization of MPs in water.

2,998

项与 药明生物技术有限公司 相关的新闻(医药)2025-08-26

政策变革、成本失控、资金管理缺陷、新旧逻辑未及时切换,叠加外部风险,共同构成了中小型医药流通企业相继“倒下”的核心诱因。

撰文| 润屿

1.48万医药流通企业,再度出现剧烈的波动,区域型小龙头已经打响“倒闭”“关停”第一枪。

据业内消息,湖北格林药业和福建国瑞药业,近期均出现了资金链问题,正在引进国有投资者。前者因一笔投资周转失灵,后者系全国各商业和各工业集中挤兑,面临资金集中支付、全国商业大部分账期取消、供应体系失衡问题,导致部分供应商无法如期支付货款。

这并非个例。自去年以来,多家在当地市场享有一定份额的区域型、中小型医药流通企业,或传统配送商,都出现了生存危机和经营困境,不乏有营收体量在TOP30里的上市公司,在外部压力和内部合规问题双重挤压下逐渐边缘化。

有业内人士预测,未来5-10年内,超60%的医药商业公司将面临生存危机。这背后,一条旧的产业逻辑正逐步失灵。

中小企业,接连“爆雷”

下降2.9%。

中康产业研究院最新预测,2025年中国药品终端市场销售规模约2万亿元,仍呈现负增长的冷峻态势,其中医院同比下降5.7%。依赖购销差价盈利的企业,正在承受生存压力。

首先来看一组数字。中国专注于医药流通业务的上市公司约22家,按照年报来看,22家公司2024年扣非归母净利润较上年下滑了10个百分点;收入增速、扣非净利润增速降至2017年来最低;另外,整体毛利率和净利率均有所下降。

其中,“4+N”格局中的4家千亿寡头——国药控股、上海医药、华润医药、九州通,虽然地位孑然不动,但除了上药之外,各家企业的利润均不同程度承压。“大哥”国药控股2024年出现上市来营收、净利润首次下滑情况。2025年H1,国药控股净利润达53.37亿元,同比下降9.53%;其医药分销收入达2185.27亿元,下滑3.52%。

剩下的18家公司,多数为央企和地方国企、少数为民企,他们可谓是支撑起流通行业的中部力量,然其中大部分企业的日子都不太好过。

重药控股,于今年4月被查,系2023年年报存在信息披露违规问题;其利润率在近几年也持续走低。

海王生物,医药商业流通规模位居全国第9名(中国医药商业协会发布的“2023 年药品批发企业主营业务收入排名”),已长期深陷业绩泥潭和债务困境,其耗时三年的国资重组“自救”计划落空,6月宣布终止控股股东变更为丝纺集团(实制人原拟变更为广东省人民政府)。

鹭燕医药,排名15,是福建最大的医药流通企业,高度依赖纯销模式,直接向二级以上公立医院供货。上半年,其归母净利润达1.55亿元,同比下滑18.83%。

昔日几百亿体量的公司瑞康医药,5年来营收连续下滑,4年扣非净利润亏损,7月其资金操盘手又突然被查。最新财报显示,上半年该公司营收达35.44亿元,同比下降12.11%,归母净利润不到1亿,同比下降32.35%。

除了22家上市公司外,情况又是如何?

首先,生存空间不甚乐观。

中国药品批发型企业数量近几年一直在上升,截至2023年约1.48万家。但从行业集中度来看,光四家“巨无霸”的规模就占据了半壁江山, TOP10药品批发企业占全国医药市场总规模比重为59.6%,TOP100的比重为76%。也就是说,百名开外,万家流通企业要在愈发狭窄的空间里夹缝生存。

如果属于大药企里的分公司,或是其县域市场的补充,暂有避风港,但那些曾享誉一方的中小型医药流通公司,就要另当别论了。

2025年,可以说医药流通行业彻底进入了一个新的阶段。这一阶段,强者恒强,同时全力向医药全生态链服务商转型。但同时,诸多昔日颇有名气的地方型流通企业,陆续打响了倒闭、关停、暂停营业的“第一枪”。

在湖北格林和福建国瑞之前,今年3月,云南民生药业因资金链断裂、供应商围堵仓库场面,已引发了行业关注。据熟悉它的人士描述,2017年的云南民生,在当地可谓风光无限。

以各种各样方式出现资金链断裂问题,不得不停止运营、苦寻国资自救的公司,水面之下,应该还有很多。

推荐阅读

* 流通暗战升级:医药千亿巨头被查,戳破了什么泡沫?

* 国药、上药、华润、九州通,5家千亿巨头就位!医药流通进入“寡头”时代

又一“新旧”交替之时

医药流通以提升集中度为结果的几次行业大整合,带动了行业的几次波动、进化和洗牌。

第一次是10年前四大“巨无霸”的上市、跑马圈地、初步给行业“4+N”格局定调;

第二次是“两票制”政策以来,处在“工业+流通+医院”中间环节的企业加价透明化,同时“倒逼”流通公司承担“垫资”职责,拉长回款周期,垫资压力加大,各家企业运营效率加速分化。“4+N”格局里,“4大全国型龙头+区域龙头+偏远散户”结构发生着动态调整,民营类中小型批发企业盈利能力挑战越来越大。

第三次动态演进维系至今,这一时期,四大寡头,再加一个2024年诞生的“重庆医药-中国医药联合体,在继续以收并购动作扩大体量的同时,已经全力打起了多元化能力进阶的“组合拳”。

然而,既无大树可傍,也无资源资金去做服务水平和能力进阶、更长期倚赖于单一传统模式的中小企业,集中陷入到了比以往更剧烈的风暴之中。

这场风暴,具备四大关键词。

其一,价格战。

伴随“两票制”、集采、医保控费等政策的持续推进,医药流通环节被压缩,为维持规模,部分企业采取“以价换量”,价格竞争随之加剧。

同时,全国1万多家药品批发企业,要在不到30%的市场份额中生存,为争夺有限的市场份额,企业通过降价吸引客户,尤其在基层医疗市场和零售药店领域,价格战成为常见竞争手段,但靠低价抢客户绝非长久之计。

其二,收账款周转效率分化。据中国医药商业协会统计,2023年药品批发企业对医疗机构应收账款回款天数平均达152天,相继上年增加,医疗机构拖欠药品批发企业货款问题仍未改善。

这一点,唯有前4家“寡头”相对乐观,中尾部企业的表现,就看谁的资金池更深厚、能扛住应收账款回款周期了。

受此影响,鹭燕医药等企业的应收账款在持续攀升,海王生物、瑞康医药、国发股份等民营企业的应收账款周转天数相对较高,账款周转压力较大。其中,海王生物的资产负债率一直远高于上药、九州通等业内同行,高负债、长账期、商誉减值等多重问题待解。

其三,企业没有做好合规内控。

其四,下游客户结构生变。“处方外流”趋势下,下游客户结构逐渐发生变化,院外“话语权”越来越大,但很多中小型企业未提前布局院外分销网络。

如何抵御风暴的冲击?这一问题,就是当下决定流通企业能否活下去的关键。

答案很简单,头部流通企业怎么做的,就跟着怎么做。

向医药工业延伸,做药,典型如上药;布局CSO业态,除了四大“巨无霸”,区域性流通龙头英特集团也正在这么做。

往下游走,立稳院外零售市场。

加强医药供应链服务平台建设,发展院内物流管理系统(SPD)项目,助力医院医疗物资管理提质增效。

向多品类——如医美、特医食品、生物制剂、诊断试剂、宠物食品等延伸,打造新的“标签”,或者跨界跨行做别的生意。最典型的企业如九州通,不仅认真做起了医美业务,研究起了“中药助眠”,而且正准备低调卖电车。

然而,囿于资源禀赋的绝对差距、市场博弈的劣势地位、以及自身对传统路径的长期依赖,很多中小型企业做起来并没有那么容易。结局好点的,顺利找到国资“接手”,筹备期间不生别的波澜,或被寡头时代的“四大天王”收购,再或者找到业内伙伴,共同探索新模式、新业态。

但要是运气差点,也许会“消失”在这场风暴里。

一审| 黄佳

二审| 李芳晨

三审| 李静芝

精彩推荐

大事件 | IPO | 融资&交易 | 财报季 | 新产品 | 研发日 | 里程碑 | 行业观察 | 政策解读 | 深度案例 | 大咖履新 | 集采&国谈 | 出海 | 高端访谈 | 技术&赛道 | E企谈 | 新药生命周期 | 市值 | 新药上市 | 商业价值 | 医疗器械 | IND | 周年庆

大药企 | 竞争力20强 | 恒瑞 | 石药 | 中生制药 | 齐鲁 | 复星 | 科伦 | 翰森 | 华润 | 国药 | 云南白药 | 天士力 | 华东 | 上药

创新药企 | 创新100强 | 百济 | 信达 | 君实 | 复宏汉霖 | 康方 | 和黄 | 荣昌 | 亚盛|康宁杰瑞|贝达|微芯|再鼎|亚虹

跨国药企|MNC卓越|辉瑞|AZ|诺华|罗氏|BMS|默克|赛诺菲|GSK|武田|礼来|诺和诺德|拜耳

供应链|赛默飞|药明|凯莱英|泰格|思拓凡|康龙化成|博腾|晶泰|龙沙|三星

启思会 | 声音·责任 | 创百汇 | E药经理人理事会 | 微解药直播 | 大国新药 | 营销硬观点 | 投资人去哪儿 | 分析师看赛道 | 药事每周谈 | 中国医药手册

财报

2025-08-25

一味固守传统模式,是商业惰性。“中药印钞机”片仔癀营收与净利首次“双崩”,并非短期波动所致,而是其依赖稀缺配方提价、区域市场集中等传统增长逻辑,与行业诸多新趋势逐渐脱节的必然结果。

撰文| 张烨静

“中药茅”的业绩,罕见“爆雷”了。

8月23日,片仔癀发布2025年半年度业绩快报,公司上半年营收达53.79亿元,同比下降4.81%;归母净利润达14.42亿元,同比下滑了16个百分点。

梳理财报发现,片仔癀上一次出现半年报净利下滑的情况,还是在2014年。此后的十年间,任凭中药行业起起落落,片仔癀中报始终保持着营收、净利双增的态势。

而此次罕见的业绩表现,暴露了又一家中药老字号固守传统经营模式而显现出的战略滞后性。与其说是其核心产品的销售困境,不如说是一套传统过时的产业逻辑,正在被市场重新审视。

十年“中药茅”,一朝失宠?

大名鼎鼎的片仔癀,是一款由牛黄、麝香、蛇胆等中药材为主要原材料的经典名方,不仅主要原材料稀缺,其配方更入选国家保密配方名单。凭借这些特性,片仔癀一度成为传统高端礼品,甚至作为投资升值的“奇货”,被誉为“药中茅台”。

手握这款“奇货”的企业——片仔癀药业,曾是中药界的一棵“常青树”。尤其是2022年,中药行业整体增速放缓,但当年片仔癀的半年报,仍取得了营收同比增14.91%、净利同比增17.85%的亮眼成绩。

因此,此次营收净利双降,无异于又一个“市值神话”的陨落。

据片仔癀药业的业绩快报,该企业将主要原因归结为以下两方面:一方面,为保障片仔癀系列产品销售收入的稳健态势,公司战略性增加了销售费用的投入。另一方面,公司生产所需的关键原材料价格持续处于历史高位运行,成本压力显著增大。

此外,研发与管理费用也是经费承压的原因之一。片仔癀药业正在推进2个新药立项,18个在研新药及经典名方的研发项目;公司于2024年底在北京投资建设的北方总部已进入初期运营阶段,增加了公司的管理费用。

短短百字,却意味着片仔癀长达十年的增长惯性和产业逻辑被打破。究竟发生了什么?

事实上,受系列复杂的市场需求、政策支持和气候变化等因素,中药材会出现价格变化。

而从2023年底,中药材掀起了一股相对剧烈的涨价风波。彼时,一些中成药企业因毛利率持续承压,无奈断供集采,例如同仁堂、康美、振东等企业。在这场涨价风波中,片仔癀带来成本压力的关键原材料——“天然牛黄”也不能幸免。

2023年之前,天然牛黄的价格保持着相对较为缓慢的增长态势,从2014年的20万元/公斤缓慢上升至约50万元/公斤。从2023年开始,这一价格迎来持续地快速上涨。2023年1月的价格还在65万元/公斤,到2025年1月就飙到了165万元/公斤,涨幅超150%,已经远超黄金价。

对于以原料稀缺性为卖点的片仔癀来说,这一价格变动直击产品命脉。面对巨大的成本压力,片仔癀持续了其一贯的提价策略。依据它的过往经验,这往往伴随着后续业绩的增长。

片仔癀最近一次提价在2023年5月,公司因“原料及人工成本上涨”,把片仔癀锭剂国内零售价从590元/粒涨到760元/粒,单粒涨幅近30%。而往回看,据西南证券统计,2004年至2020年,片仔癀锭剂一共提价19次,零售价从325元/粒升至590元/粒。

不过这一次,事情没有按照一贯的轨迹发展。

回看今年上半年片仔癀的业绩,在营收只下降4.81%的情况下,净利润同比下降了16.22%。可以理解为,尽管终端提价给片仔癀吊了一口气,营收数据没有太难看,但到手的利润大幅缩水,在原料涨价与产品提价的竞赛中,产品提价还是跑输了——提的跟不上涨的。

更关键的问题在于,“无限度提价”策略能够有效的前提是,需求端愿意为之买单。但很明显,如今的消费市场已然大不同前。

一方面,高端品没那么好卖了。在当前理性消费主导的市场环境下,曾经很多暴利、“高端”的生意变得不再好做,诸多赛道明星企业不得不转型求增量,医美、保健品等业内的头部企业,上半年业绩“暴雷”的不在少数。随着近些年大众的消费需求转变,作为高价保健药品的片仔癀,已经不再是传统的“市场宠儿”。

另一方面,反复的提价引发了市场反感。经济学里有一种“凡勃伦效应”,说的是商品价格越高,消费者反而越愿意购买。但当价格高到一定程度,超出了其所能承载的“社交炫耀”价值,它反而会引起消费者的反感和排斥,导致需求锐减。片仔癀大概成于此,也败于此。

除了消费者,还有一个关键的角色是渠道商。和茅台酒有类似性,片仔癀的渠道商(经销商、药店)倾向于囤积药品,期待炒作以赚取差价。

片仔癀药业年报及一季报显示,公司应收账款增速均大幅高出营收增速,这说明,当终端销售速度放缓后,渠道库存在一定程度上被大量积压。

推荐阅读

* 中药材猛涨,断供高发。同仁堂、以岭、片仔癀直呼“顶不住”…

* 中药业绩“雪崩”,2025靠什么翻盘?

“高端”的老路走不通了

此前,片仔癀药业在其独家创新药的运营上,遵循着一套非常清晰且固定的商业逻辑。通过营销产品稀缺独特性,走入高端市场,再利用产品定位进行反复提价,最终获得产品形象和营收数据的双赢局面。

这是一套“强品牌+高毛利+高现金流”的打法。事实已然验证,这套逻辑是其成功的基石,但并非长久之计。

无独有偶,曾经采用过这一套产业逻辑的企业,不只片仔癀一家,还有东阿阿胶、同仁堂等中药企业。

东阿阿胶曾凭借“阿胶,出东阿”的品牌认知和“驴皮紧缺”的稀缺逻辑,不断进行提价,连续多年实现收入和利润的双增长,并在2015年登上业绩顶峰,净利润超过20亿元,净资产收益率超过25%。

但到了2019年,东阿阿胶迎来其1996年上市来的首亏:营收29.59亿元,较上年同期下滑59.68%,归属于上市公司股东净利润-4.44亿元,同比下降121.29%。

历史总是惊人的相似。当时东阿阿胶给出的原因,与此次片仔癀爆雷的原因高度一致——受整体宏观环境以及市场对价值回归预期逐渐降低等因素影响,公司渠道库存出现持续积压。

进一步拆解开来,东阿阿胶的亏损主要是三方面原因:原料驴皮成本上涨、经销商大量囤积货品、阿胶在消费端“价值回归”。

再看同仁堂的安宫牛黄丸。同仁堂的收入高度依赖于安宫牛黄丸这一大单品,同样陷入“增收不增利”的局面中。2024年,其全年营收185.97亿元,同比增长4.12%,但归母净利润同比下滑8.54%至15.26亿元,扣非净利润降幅达10.55%。在成本端,其2024年营业成本同比增长10.7%,中药材价格上涨23.07%。

可以说,安宫牛黄丸的发展逻辑和片仔癀类似,在原料成本暴涨和需求疲软的双重压力下,很难不为它捏把汗。

必须寻找新的路。

好在总有人先摸着石头过河。近两年,东阿阿胶构建了“药品+健康消费品”双轮驱动业务增长模式,以阿胶块、复方阿胶浆等核心产品巩固基本盘,健康消费品线则推出“小金条”速溶阿胶粉、阿胶奶茶等创新产品,开拓年轻化新市场。此外,还将男性滋补品作为第二曲线。

如今,东阿阿胶已逐渐从阿胶的阴霾下走出。今年上半年,东阿阿胶实现营业收入30.51亿元,同比增长11.02%;归母净利润8.18亿元,同比增长10.74%。

而片仔癀也正在积极打造新曲线——迈入消费大健康领域,做起化妆品,叠加进军生化创新药赛道(涵盖肿瘤、疼痛、精神神经等多个治疗领域),但还需要一定时间去验证。

显然,遵循传统逻辑行不通了,诸多赛道明星企业不得不转型求增量。

在这种情况下,企业在关注独家品种的“护城河”时,也需要密切关注其成本控制、新品研发、渠道健康度以及宏观消费趋势的变化。

一审| 黄佳

二审| 李芳晨

三审| 李静芝

精彩推荐

大事件 | IPO | 融资&交易 | 财报季 | 新产品 | 研发日 | 里程碑 | 行业观察 | 政策解读 | 深度案例 | 大咖履新 | 集采&国谈 | 出海 | 高端访谈 | 技术&赛道 | E企谈 | 新药生命周期 | 市值 | 新药上市 | 商业价值 | 医疗器械 | IND | 周年庆

大药企 | 竞争力20强 | 恒瑞 | 石药 | 中生制药 | 齐鲁 | 复星 | 科伦 | 翰森 | 华润 | 国药 | 云南白药 | 天士力 | 华东 | 上药

创新药企 | 创新100强 | 百济 | 信达 | 君实 | 复宏汉霖 | 康方 | 和黄 | 荣昌 | 亚盛|康宁杰瑞|贝达|微芯|再鼎|亚虹

跨国药企|MNC卓越|辉瑞|AZ|诺华|罗氏|BMS|默克|赛诺菲|GSK|武田|礼来|诺和诺德|拜耳

供应链|赛默飞|药明|凯莱英|泰格|思拓凡|康龙化成|博腾|晶泰|龙沙|三星

启思会 | 声音·责任 | 创百汇 | E药经理人理事会 | 微解药直播 | 大国新药 | 营销硬观点 | 投资人去哪儿 | 分析师看赛道 | 药事每周谈 | 中国医药手册

财报高管变更

2025-08-19

抗VEGF赛道竞争正迎来最激烈的升级时刻。

撰文| 张烨静

抗VEGF眼科药物赛场,战况再次升级。

诺华的雷珠单抗作为全球首个眼科抗VEGF药物,曾创下年销超40亿美元的巅峰战绩,至今仍是市场重要玩家;罗氏的法瑞西单抗则以VEGF-A/Ang2双靶点优势异军突起,2024年销售额达44亿美元,上市三年复合增长率68%,正剑指市场第一。

两位老牌劲旅,一个是市场先发者,一个规则改写者,两家先后构筑起稳固壁垒。

如果聚焦至国内战场,本土力量已形成强势围剿之势。康弘药业的康柏西普作为国产首款抗VEGF单抗,2024年销售额达23.43亿元,不仅打破进口垄断,更超越雷珠单抗登顶国内眼科用药榜首;齐鲁制药则凭借首款贝伐珠单抗、阿柏西普及雷珠单抗生物类似药,也快速切入市场分羹。

在市场的激烈厮杀中,一个重磅BD合作又给这个赛道添了把火。

8月19日,荣昌生物发布公告称,将VEGF/FGF融合蛋白RC28-E在大中华区、韩国、泰国、越南、新加坡、菲律宾、印度尼西亚及马来西亚的权益授权给参天制药。根据该协议,荣昌生物将获得2.5亿元预付款,5.2亿元开发及监管里程碑,5.25亿元销售里程碑,以及高个位数至双位数百分比的销售分成,协议总金额13.95亿元。

无疑,当百年眼科巨头也跃跃欲试地“杀入”这条眼底病药物赛道,进口与国产的多强混战将更加激烈。

抗VEGF药物,打响升级战

随着全球老龄化加剧及眼底疾病(如:wAMD、DME、RVO)患者基数扩大,抗VEGF眼科药物也进入了更焦灼的竞争时代。

据统计,2024年全球抗VEGF眼科药物市场规模约230亿美元,预计2030年将突破400亿美元,年复合增长率(CAGR)达11%。此外,2024年中国市场规模约130亿元,预计2025年突破200亿元,增速全球领先。

VEGF药物是当前眼底疾病的核心治疗手段。这是一类能促进新生血管生成和增加血管通透性的信号分子。在糖尿病患者中,高血糖会导致视网膜缺氧,缺氧环境刺激视网膜细胞大量分泌VEGF。因此,通过抑制VEGF活性,能减少渗漏和水肿,保护黄斑结构。抗VEGF药物的问世,使得湿性年龄相关性黄斑变性(wAMD)和糖尿病性黄斑水肿(DME)、视网膜静脉阻塞(RVO)等眼底疾病治疗取得了历史性突破。

截至目前,全球共有5款抗VEGF眼科药物获批上市,包括诺华的雷珠单抗(Lucentis)和布西珠单抗(Beovu)、再生元的阿柏西普(Eylea)、康弘的康柏西普(Langmu)和罗氏的法瑞西单抗(Vabysmo)。其中,雷珠单抗和贝伐珠单抗是单靶点VEGF抑制剂,阿柏西普和康柏西普靶点VEGF-A/B和PlGF,法瑞西单抗靶点VEGF-A和Ang2。

回顾抗VEGF眼科药物的发展历程,不难瞥见一些在这条赛道中致胜的趋势。

2006年,诺华的雷珠单抗获FDA批准上市,成为全球首个获批用于眼科的抗VEGF药物,其抗VEGF疗法在很大程度上取代了以前的治疗策略,也由此拉开了抗VEGF药物的竞争序幕。

自上市以来,雷珠单抗全球销售额便基本维持在年销售额30亿美元这个量级,2014年雷珠单抗迎来销售峰值,超40亿美元。

直到2015年,再生元的阿柏西普凭借更合理的定价和优秀的疗效,全球销售额首度超越雷珠单抗,并且此后二者差距逐渐拉开。2020年,阿柏西普在全球的销售额接近80亿美元,而此时的雷珠单抗,全球销售额已回落至33.77亿美元。

单靶点VEGF药物已不能满足临床需求。近些年,双靶点药物已逐渐成为抗VEGF药物治疗眼科疾病的重要研发方向之一,其中罗氏研发的法瑞西单抗(Vabysmo)一经上市就显示出巨大的市场潜力。

2022年,法瑞西单抗上市,是目前唯一获批的双靶点VEGF眼科药物。凭借双靶点协同作用和长效优势,法瑞西单抗上市后增长迅猛,2024年全球销售额达44亿美元左右,上市三年的复合年增长率(CAGR)高达68%。

法瑞西单抗的市场策略聚焦于差异化技术优势,通过双靶点机制增强疗效并延长给药周期,预计未来两三年内可能超越阿柏西普成为市场领导者。

法瑞西单抗的市场热度,暗示着眼底病治疗领域正步入双靶点时代的新篇章。而正如荣昌与参天的这笔交易,RC28-E是VEGF和FGF双靶点药物。

具体到RC28-E,能够应对眼科新生血管治疗的“抗纤维化”问题。在眼底病中,黄斑下纤维化是导致视力不可逆丧失的主要原因之一,且是现有单一抗VEGF疗法长期治疗效果的瓶颈。RC28-E的FGF靶点主要通过促进成纤维细胞活化、调节细胞外基质代谢和与炎症细胞相互作用等机制推动纤维化进展,有望成为改变wAMD和DME疾病预后的“规则改变者”。

可见,参天拿下 RC28-E,不仅是产品补充,更是对眼科创新下一个窗口的押注。

推荐阅读

* 一哥“杀入”眼科神药赛场,兴齐、齐鲁夹击,破局还是混战?

* 市值一年蒸发4800亿,专利悬崖逼近,这家顶级Biotech陷入“中年危机”

下一站:从 “红海竞逐” 到 “价值重构”

参天与荣昌的合作,意味着国内抗 VEGF 赛道再添重磅玩家。数据显示,中国目前有 570 万名临床显著的 DME 患者、381 万名 wAMD 患者,2021 年糖尿病患者超 1.4 亿 —— 庞大的患者基数,让赛道成为必争之地。

市场潜力吸引着全类型参与者,形成多层次竞争格局。

一方面,是国内老牌选手的市场底盘。

国内抗VEGF的先发者非康弘药业莫属。早在2013年11月,康柏西普就在国内获批上市,是全球第三款、国内首款国产VEGF单抗,也是国内仅次于雷珠单抗的第二款上市销售的VEGF单抗。它填补了国内眼底黄斑变性治疗药物的市场空白,也打破了高价进口药对中国眼科市场的垄断。

2019年至2023年,康柏西普连续5年销售额突破10亿元人民币,分别为11.55亿元、10.87亿元、13.2亿元、13.66亿元、19.36亿元。2023年,康柏西普更是首次超越雷珠单抗,拿下2023年全国等级医院眼科用药销售额TOP10的第一名。2024年,其全年销售额为23.43亿元,同比增长20.98%,占公司总营收的52.61%。

另一方面,是多款类似药的步步紧追。

过去很长时间以来,国产抗VEGF药物主要集中在仿制与类似药开发阶段。随着阿柏西普、雷珠单抗、贝伐珠单抗的关键专利陆续到期,国内生物类似药研发也进入收获期。

齐鲁制药是类似药里一个不可忽视的强者。2019年,齐鲁制药安可达获批上市,是国内首个获批的贝伐珠单抗生物类似药;2023年12月,其研发的阿柏西普生物类似药上市。2024年8月,齐鲁制药的雷珠单抗注射液又获批上市,成为国内首个获批的雷珠单抗生物类似药,使其成为国内眼科赛道的强将。

此外,欧康维视与博安生物合作开发的OT-702也已申报上市,迈威生物和景泽生物的类似药处于III期临床阶段,并且国内还有多款生物类似物在研。

第三方势力则是本土创新药企押注的“下一代技术”,比如恒瑞、信达、奥赛康也纷纷聚焦在各自技术领域,希望分的一杯羹。

恒瑞的HR19034也属抗VEGF双抗,靶向VEGF两个不同表位以增强抑制效果。2024年完成II期临床,今年进入III期临床,与阿柏西普头对头比较,预计2026年提交上市申请。

信达生物在抗VEGF赛道也有布子。今年5月5日ARVO 2025年会上,信达生物口头报告了其全球首个创新型双靶点分子IBI302(抗VEGF-抗补体双功能),在新生血管性年龄相关性黄斑变性(nAMD)患者中对比阿柏西普的II期研究结果。

奥赛康的ASKG712与罗氏的法瑞西单抗为相同靶点,同属于VEGF-A/Ang-2双特异性抗体,抑制血管渗漏并增强血管稳定性。今年5月奥赛康公布了I期临床数据(NCT05940428),并计划2026年启动II期试验。

从康弘的初代突破到齐鲁的类似药追赶,从跨国药企的技术迭代到恒瑞、信达的创新押注,再到参天携荣昌的跨界入局,抗 VEGF 赛道已集齐跨国巨头、本土龙头、创新 Biotech 等全类型玩家,竞争维度从 “价格战” 转向 “技术战”“生态战”。

未来,抗 VEGF 赛道的决胜关键,或许不在于 “打败对手”,而在于谁能率先突破现有治疗的天花板,让更多眼底病患者留住光明。因为对行业而言,激烈竞争将倒逼企业聚焦未被满足的需求:如更便捷的给药方式、更广泛的适应症覆盖、更精准的个体化治疗。

一审| 黄佳

二审| 李芳晨

三审| 李静芝

精彩推荐

大事件 | IPO | 融资&交易 | 财报季 | 新产品 | 研发日 | 里程碑 | 行业观察 | 政策解读 | 深度案例 | 大咖履新 | 集采&国谈 | 出海 | 高端访谈 | 技术&赛道 | E企谈 | 新药生命周期 | 市值 | 新药上市 | 商业价值 | 医疗器械 | IND | 周年庆

大药企 | 竞争力20强 | 恒瑞 | 石药 | 中生制药 | 齐鲁 | 复星 | 科伦 | 翰森 | 华润 | 国药 | 云南白药 | 天士力 | 华东 | 上药

创新药企 | 创新100强 | 百济 | 信达 | 君实 | 复宏汉霖 | 康方 | 和黄 | 荣昌 | 亚盛|康宁杰瑞|贝达|微芯|再鼎|亚虹

跨国药企|MNC卓越|辉瑞|AZ|诺华|罗氏|BMS|默克|赛诺菲|GSK|武田|礼来|诺和诺德|拜耳

供应链|赛默飞|药明|凯莱英|泰格|思拓凡|康龙化成|博腾|晶泰|龙沙|三星

启思会 | 声音·责任 | 创百汇 | E药经理人理事会 | 微解药直播 | 大国新药 | 营销硬观点 | 投资人去哪儿 | 分析师看赛道 | 药事每周谈 | 中国医药手册

上市批准引进/卖出生物类似药

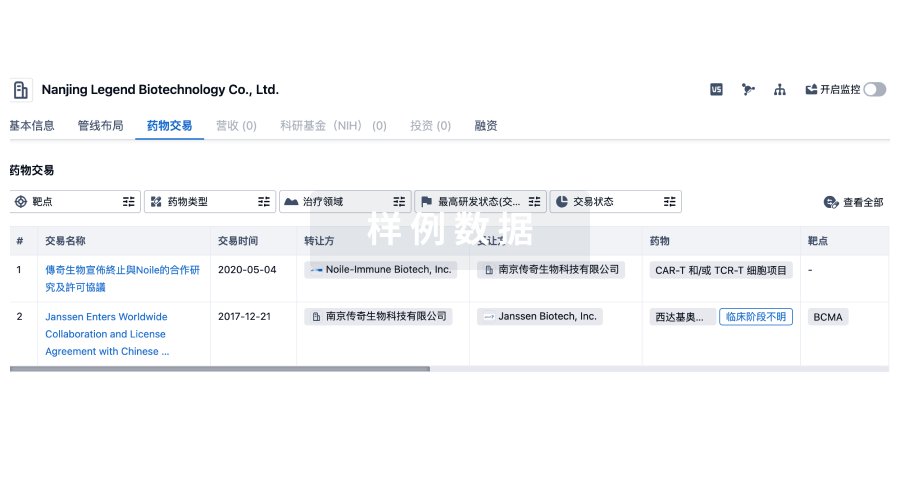

100 项与 药明生物技术有限公司 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

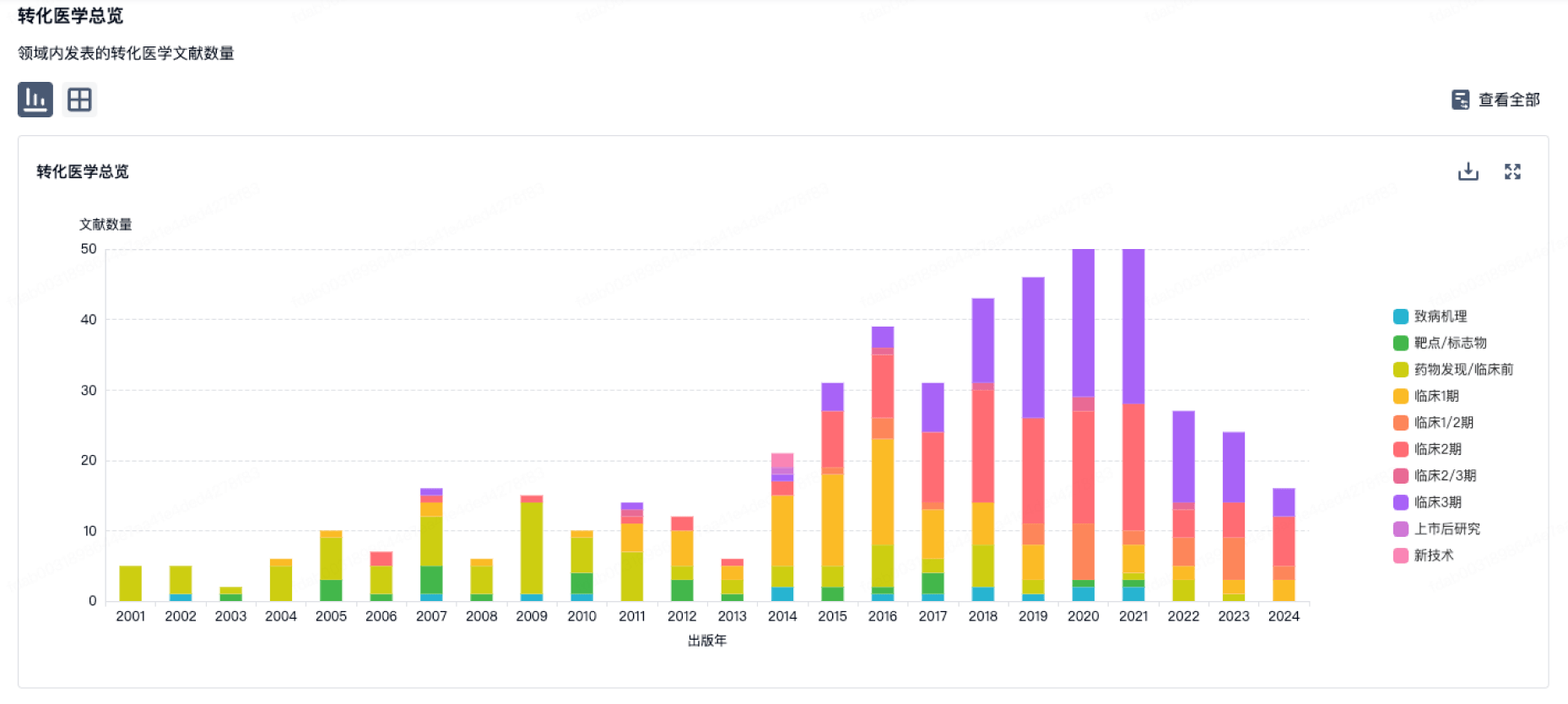

100 项与 药明生物技术有限公司 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

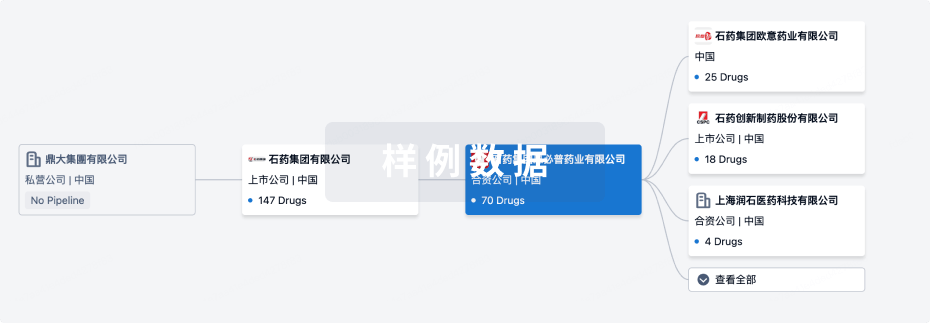

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2025年09月05日管线快照

管线布局中药物为当前组织机构及其子机构作为药物机构进行统计,早期临床1期并入临床1期,临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

药物发现

7

1

临床前

其他

6

登录后查看更多信息

当前项目

| 药物(靶点) | 适应症 | 全球最高研发状态 |

|---|---|---|

S-309 ( SARS-CoV-2 S protein ) | COVID-19 呼吸道感染 更多 | 临床前 |

US20230203159 ( CD3ε )专利挖掘 | 罕见病 更多 | 药物发现 |

WO2024109792 ( PSMA )专利挖掘 | 错构瘤 更多 | 药物发现 |

WO2024098180 ( TSLPR )专利挖掘 | 皮肤和结缔组织疾病 更多 | 药物发现 |

WO2024146539 ( PDL1 )专利挖掘 | 炎症 更多 | 药物发现 |

登录后查看更多信息

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

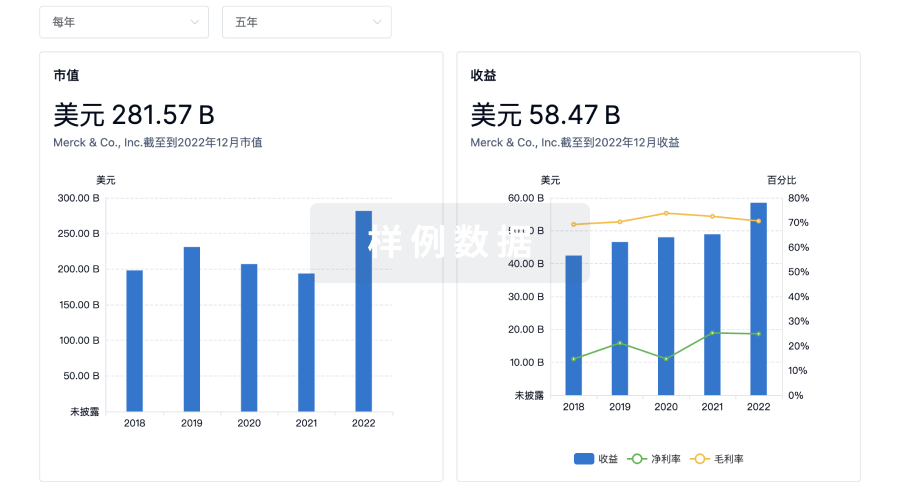

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

Eureka LS:

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用