预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

Mahzi Therapeutics, Inc.

更新于:2025-05-07

概览

标签

神经系统疾病

其他疾病

遗传病与畸形

基因疗法

腺相关病毒基因治疗

ASO

关联

4

项与 Mahzi Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的药物靶点 |

作用机制 TCF4 modulators |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

靶点- |

作用机制- |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

靶点- |

作用机制- |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

100 项与 Mahzi Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 Mahzi Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

5

项与 Mahzi Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的新闻(医药)2025-05-03

Welcome back to Endpoints Weekly, our roundup of the top headlines in biopharma. Earnings season continued this week, with more comments from pharma executives on the potential impact of tariffs, new details around Pfizer and Moderna’s cost-efficiency efforts, and more. Read below for a recap of the top news out of this week’s earnings calls.

We’ve also got a summary of data out of the American Association for Cancer Research’s annual meeting, where Lei Lei Wu reported from Chicago. And

Endpoints News’

Andrew Dunn welcomed Arc Institute co-founder Patrick Hsu to our special Slack channel to discuss all things AI.

Stay tuned next week as more companies, including BioNTech, Novo Nordisk, Takeda and more, report their earnings. —

Nicole DeFeudis

💲 More pharma companies reported their Q1 earnings this week,

including AstraZeneca, Novartis, Pfizer, GSK, Eli Lilly, Moderna and Amgen. Tariffs were a

central theme

during earnings calls, as drugmakers provided some detail on the potential impact to their business.

“Our goal, as I mentioned, is to have 100% of our products produced in the US for the US,” Novartis CEO Vas Narasimhan said during a first-quarter earnings call with the media Tuesday. AstraZeneca CEO Pascal Soriot said the company “can actually move the manufacturing of products that are made in Europe, move it to the US for supply to the US. And we can also potentially do the other way around.”

Here’s what else our reporters tracked:

The privately-held biotech Stealth BioTherapeutics

said its

rare disease drug was delayed

this week. A person familiar with the situation said the company hadn’t been asked to run more trials or provide more data, that the FDA hadn’t identified any safety concerns, and that the agency hadn’t raised manufacturing issues, Endpoints’ Max Gelman reported. The apparent delay comes amid

upheaval

at health agencies, though several companies have said in earnings calls and interviews in recent weeks that they aren’t seeing an impact on their interactions with the FDA so far.

The agency made decisions on time for two other drugs this week: Johnson & Johnson’s rare disease drug Imaavy and Satsuma Pharmaceuticals’ migraine drug Atzumi. The agency also hit PDUFA dates for other big-name medicines in recent weeks, like Dupixent, Amvuttra, Uplizna and Eylea.

Stealth’s drug had an original decision deadline in January, but the company said the FDA requested more time to review supplemental material. Max examines lingering questions around the situation

here

.

AACR recap: Data from GSK, Merck and more

🔬Scientists descended on Chicago this week

for the American Association for Cancer Research’s annual meeting. Some in attendance, including cancer scientists, former NIH leaders and patient advocates, spoke about how cuts to science funding could impact cancer research. “It is a time to be clear-eyed about what is happening and to decide what role each of us is willing to play,” Yale oncologist Patricia LoRusso said during a panel. Read more

here

.

Elsewhere, GSK presented data

showing that its PD-1 inhibitor Jemperli

induced a 100% complete response rate

in 49 patients with a specific type of rectal cancer after six months. Even though the results were excellent, Endpoints’ Elizabeth Cairns reported that they are unlikely to have major commercial implications. Jemperli is already approved in this cancer type, known as mismatch repair deficient (MMRd) solid tumors, though only after the patient has progressed on prior treatment and has no further options. The new data could move the product into the neoadjuvant setting for dMMR cancers, but it’s still a tiny patient population. Only around 3% of solid tumors carry the dMMR biomarker.

Merck also impressed with Keytruda data

in head and neck cancer, showing that adding Keytruda before and after surgery

cut the risk of disease recurrence or death

by 27%. Patients in the study remained disease-free for more than four years at the median.

🌎 The US’ drug infrastructure has historically been robust,

making it an attractive country in which to run clinical trials. But some companies say uncertainty is driving them to look elsewhere for their studies. Jared Whitlock examined this phenomenon in a

story this week

.

Of note, companies find FDA Commissioner Marty Makary’s comments

on rare disease approval pathways and animal testing largely promising. “Since we are in the ultra-rare disease space, Makary’s words on creating paths for rare [diseases] creates hope, and we are looking forward to learning more about his plans,” Mahzi Therapeutics CEO Yael Weiss said.

While overseas trials have limitations, agencies in Europe, Canada, Australia and the UK have worked in recent years to harmonize guidelines with the FDA.

🎤 Endpoints’ Andrew Dunn welcomed Patrick Hsu to the newsroom’s Slack channel earlier this month to share his thoughts from the frontlines of the AI bio space. Hsu co-founded the Arc Institute in 2021, a Palo Alto, CA-based nonprofit research organization that has spearheaded some leading AI biology research. “I think AI will become a universal copilot that we use for everything,” he said during the interview.

Read more here

.

DON’T MISS:

上市批准

2025-05-01

When Siren Biotechnology CEO Nicole Paulk learned last month that top FDA official Peter Marks had

resigned

, she began looking outside the US for a place to host a planned clinical trial.

The US has traditionally attracted drug studies with its robust infrastructure, diverse patient population and a smoother regulatory path to the world’s largest pharmaceutical market. But growing uncertainty over the FDA’s timelines and approval processes appears to be accelerating an existing paradigm: US drugmakers testing their drugs abroad.

That follows the Trump administration’s cuts to the FDA and the departure of high-profile officials like Marks, who cited vaccine misinformation promoted by HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. in his resignation letter. Although best known for regulating vaccines, Marks also oversaw the review of cell and gene therapies.

San Francisco-based Siren, which developed a gene therapy targeting aggressive brain cancers, has been pursuing FDA approval to start human testing in the US. But after Marks’ departure, the company is considering Canada for what could be a more predictable regulatory environment.

“If I knew the FDA’s position definitively on certain regulatory pathways, that would be very different. But you can’t put all your eggs in one basket,” Paulk said.

In a statement forwarded by a spokesperson, the FDA said “companies can remain confident in the strength, stability, and reliability of the FDA’s regulatory processes,” and that the agency is “not seeing any interruption in core program functions.”

Likewise, some companies say that the FDA’s engagement has not fallen by the wayside,

including vaccine maker GSK

.

FDA Commissioner Marty Makary meanwhile has vowed to

accelerate approvals for rare disease therapies

, reduce animal testing requirements and streamline development timelines. For companies, his words are promising but only aspirational at this point.

“Since we are in the ultra-rare disease space, Makary’s words on creating paths for rare [diseases] creates hope, and we are looking forward to learning more about his plans,” Mahzi Therapeutics CEO Yael Weiss said.

Mahzi, which is working on treatments for rare neurodevelopmental disorders, plans to seek regulatory approval to launch a clinical trial for a therapy targeting Pitt-Hopkins syndrome that causes developmental delays.

The San Francisco company is exploring options abroad, in hopes of starting the study faster and due to “regulatory review timeline uncertainties,” Weiss said.

Fears over regulatory delays grew even more real on Tuesday, when

Stealth Therapeutics said the

FDA would not meet its deadline for approving or rejecting the company’s rare disease drug.

A person familiar with the situation said the company hadn’t been asked to run more trials or provide more data, that the FDA hadn’t identified any safety concerns, and that the agency hadn’t raised manufacturing issues — typical reasons for why it might reject a drug,

Endpoints News

reported.

Camille Samuels, who sits on various biotech boards, said that several companies she advises were already looking at the UK and Australia for early-stage studies, and that “the disaster that is the FDA only heightens the desire to explore that option.”

While an inviting concept now, experts urge companies not to make hasty decisions in case regulatory headwinds dissipate.

“My personal counsel, if someone did call me with that request, would be to just sit down, chill out and make a coffee,” said Anthony Davies, CEO of Dark Horse Consulting, which advises cell and gene therapy companies.

There are signs that the portion of clinical trials in the US is declining.

According to data

from the World Health Organization, about 20% of trials were conducted at least in part in the US in 2015. That percentage has declined over the last decade, to about 15%, as countries such as China and India have taken more share.

With confidence in the FDA wavering, countries across the world are stepping up campaigns to attract clinical trials that bring in billions in research funding, create jobs and support biotech hubs.

“While much public attention has focused on efforts to lure disillusioned US scientists, you could say similar initiatives exist to attract clinical trial activities,” said Aman Khera, a consultant and president of The Organisation for Professionals in Regulatory Affairs.

Even before the Trump administration, some US companies said that FDA bureaucracy and regulatory hurdles have enticed companies to go abroad for clinical trials. It can be less expensive and quicker to start testing drugs elsewhere.

Much of the recent interest in foreign clinical trial sites is coming from small to mid-sized biotech companies that face budget pressures due to an industry downturn. But even large pharma companies — which have long run multinational studies to obtain regulatory clearance in multiple regions — are looking to increase their international capacity, according to consultants.

Many companies are “showing interest in or have already taken steps to move clinical trials overseas” in response to the FDA reorganization, Khera said.

QurAlis, a Cambridge, MA-based company developing drugs for neurodegenerative diseases, was looking to run a Phase 2 clinical trial for an undisclosed program only in the US. But after FDA layoffs were announced, the company is now pursuing a multinational approach.

“There is a reorganization ongoing, and that has an impact,” QurAlis CEO Kasper Roet said. “And the impact at the very least builds in uncertainty.”

To some extent, international trials are more feasible because agencies in Europe, Canada, Australia and the UK have worked in recent years to harmonize guidelines with the FDA, whose decisions carry outsized weight globally

.

Still, overseas trials have limitations. Data from foreign trials may not always satisfy a common FDA requirement that study data reflect the US population.

Genetic or environmental differences among patient populations can complicate results, and so “running local studies ensures that data reflects the target population’s safety and efficacy outcomes,” Khera said.

For that reason, companies have incentive to run at least a portion of the studies for a drug in the US.

临床2期疫苗

2024-12-04

Two years ago, GeneDx was teetering. The genetic testing company had laid off 33% of its staff, shares were down 90% from a year prior, and some investors were skeptical of a turnaround plan.

Since then, GeneDx has quietly managed a comeback. Its core business of pinpointing tough-to-diagnose diseases is thriving, the stock has bounced back, and it’s trying to broaden its business by using its genetic and clinical data to help drugmakers hunt for new medicines.

“We’re a small part of the rare disease journey in that we diagnose disease,” GeneDx CEO Katherine Stueland told

Endpoints News

in an interview. “And we’re really turning our attention to how we can work more effectively in the ecosystem and put our data to work in other ways.”

Those “other ways” include discovering drugs, which might be the most intriguing idea — and the hardest. Companies have long used genetic findings as the springboard for new medicines, but GeneDx is betting its data will provide a surer path. The strategy has echoes of 23andMe, a genetic testing company that has struggled to pivot to medicine.

Like 23andMe, GeneDx is helping drugmakers find new targets and refine their approaches. Unlike 23andMe, GeneDx hasn’t sought to develop its own drugs.

The plan to help discover drugs began with GeneDx’s core business of finding mystery ailments afflicting children. Unlike other companies that test broad populations to hunt for known diseases using a small menu of genetic markers, GeneDx sequences a patient’s whole genome or exome, the part responsible for many genetic diseases.

Results are run through the company’s database, which includes genetic and clinical data from hundreds of thousands of rare disease patients. Once a diagnosis is found, patients often contend with a harsh statistic: An estimated 95% of rare diseases lack a treatment, according to the advocacy group Global Genes.

GeneDx connects patients to clinical trials or resources to jump-start medicines. But the company realized it could go further by letting drugmakers tap its rich database for leads.

Last month, the company launched a new offering, called GeneDx Discover. It’s a searchable version of its database that can zero in on variants that drive rare conditions, and maybe even common ones. GeneDx has placed a molecular bullseye on so many mutations that its data could tease out the drivers of a wide set of diseases.

For GeneDx, drug discovery is more of an opportunity right now than a major source of business. But if successful, the company could go from a comeback story to a much bigger force in the rare disease field.

23andMe is the highest-profile example of a genetics company that developed a huge dataset and then tried to pivot into becoming a therapeutics company. The idea was perhaps most appealing when drug developers were just starting to unlock genetic information to create precise new drugs.

23andMe’s tests, which are primarily marketed to consumers, look at just a small part of the genetic picture. The company analyzes DNA misspellings called single nucleotide polymorphisms, or known as SNPs.

Harvard geneticist George Church, who advised 23andMe from 2008 to 2015, recommended that the company seek more in-depth genetic data. But during this time frame, the cost was prohibitive, and 23andMe found itself locked into its business model of detecting ancestral origins and some health conditions.

“They just kept doubling down on the SNPs because they were inexpensive, and they did have first-mover advantage,” Church said in an interview.

After stalled growth and growing expenses, 23andMe announced in November that

it was closing its therapeutics division

. But the company is still helping companies find new drug targets, and seeking partners for its two drugs in clinical trials.

23andMe’s power could prove to be in aggregating data from millions of people. High-resolution genetic data aren’t always as critical when targeting more common diseases that stem from a variety of interacting mechanisms.

“We are a big supporter of GeneDx, and believe their comprehensive database focused on rare diseases is complementary to 23andMe’s large-scale genetic dataset,” 23andMe said in a statement.

Mahzi Therapeutics, a company focused on neurodevelopmental disorders, used GeneDx to develop three of its rare disease therapies that are at the preclinical stage. The company knew the conditions it wanted to target, but GeneDx’s database provided a closer look at the genetic underpinnings.

“We need to understand the targets on the gene. By getting exome or genome data, we have much more information,” Mahzi CEO Yael Weiss said.

But detailed genetic information is far from a panacea. Even when a genetic variant is linked to a disease, it can still be difficult for drug hunters to hit a designated target.

GeneDx’s database also allows drugmakers to find links between genotypes and phenotypes, the physical manifestation of genes. An understanding of the relationship helps drugmakers understand which variants to correct and helps in testing compounds.

“GeneDx offers a different approach because there’s a lot more information than just the genetic sequence. There’s a lot of clinical information,” Weiss said.

The company’s data are aggregated and de-identified. Patients must give the OK for drugmakers to access deeper levels of information, like their genomes. With an explosion in genetic data and accompanying privacy concerns, GeneDx’s website says the company uses “a range of physical, technical and administrative safeguards to secure personally identifiable information.”

GeneDx isn’t alone in trying to spark new drugs from large datasets paired with high-resolution data.

Regeneron sequenced exomes and genomes from more than 1.5 million people and notably found genes that appear to protect against obesity. The company seized on the discoveries to

develop potential weight loss medicines

.

“We really think you need to look at millions of people, even for the common diseases, to find these unique things that could really dramatically change your outcomes,” Regeneron’s chief genomics and data science officer Gonçalo Abecasis said.

Companies are also layering in data from other

sources like the proteome

, the body’s collection of proteins, to find new medicines and diagnostics.

GeneDx was founded in 2000, around six years before 23andMe, by two National Institutes of Health scientists aiming to diagnose rare conditions. As it grew, it expanded into testing for everything from Covid-19 to reproductive health issues to breast cancer.

In 2022, the artificial intelligence company Sema4 acquired GeneDx and the new owners urged focus. The company was unprofitable and part of a diagnostics trend of “trying to be all things to all people,” Stueland said.

After much introspection, GeneDx laid off 700 workers and zeroed in on its original mission of diagnosing rare conditions.

Investors didn’t initially love the moves. GeneDx’s stock plummeted to the point where the company last year was almost kicked off the Nasdaq market.

“It was a daunting experience to decide where to focus,” Stueland said. “But it became super-clear to us as a management team, to us as a board, that we were going to deploy capital towards the area where we had the distinct strength.”

Since then, the company has tapped into growing demand at hospitals for pediatric DNA sequencing. The increasing evidence for comprehensive testing has differentiated GeneDx from 23andMe in another way: getting paid.

Increasingly, insurers and government health programs cover GeneDx’s tests. With more ordering of the company’s genome and exome tests, GeneDx recently reported $77 million in quarterly revenue, and reached profitability for the first time. It now has 900 employees, is the leading player in the niche market, and its stock trades north of $75 a share.

Newborns typically have their heel pricked for blood to find up to 50 genetic diseases. But the testing misses thousands of other conditions, often rare or ultra-rare ones that aren’t known to many doctors and don’t make it into those tests. On average, it takes rare disease patients six years to get diagnosed, what’s known as the diagnostic odyssey.

GeneDx finds answers through not only comprehensive genetic testing for patients, but also by testing their parents and collecting doctor notes for more genetic clues.

Results are checked against its database with 700,000 samples. Once a disease is pinpointed, those data help find the next diagnosis.

“We’re doing the really hard job of going into each and every gene to search and identify a mutation that is causing the underlying disease,” Stueland said.

Stock analysts expect more growth because the company has just started to crack the newborn testing market. It’s a chance to move from sequencing the relatively narrow number of young patients with signs of illness, to a far larger group of healthy newborns.

The company is part of research that found 3.7% of the first 4,000 newborns who underwent whole-genome sequencing had a positive test for a genetic disease, but most of those diseases weren’t included in a list of diseases that are currently screened for. That study, called Guardian, was published in October in

JAMA

.

GeneDx has found that some common diseases are a constellation of genetic diagnoses. That could be useful for drug discovery purposes, along with another aim. The company wants to diagnose Parkinson’s and other conditions earlier, though it hasn’t detailed plans in this area.

“We’re really placing a bet on our ability to be really great at taking a genome’s worth of information and putting it to work for as many people as possible,” Stueland said.

并购

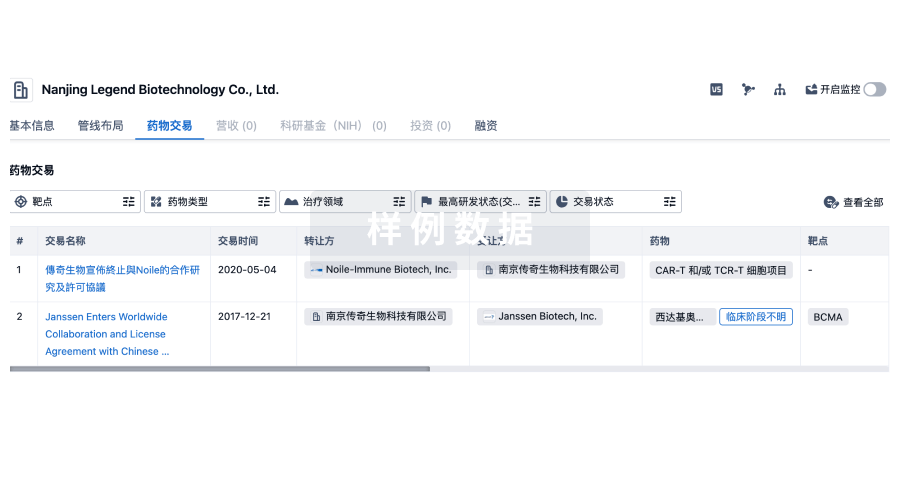

100 项与 Mahzi Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

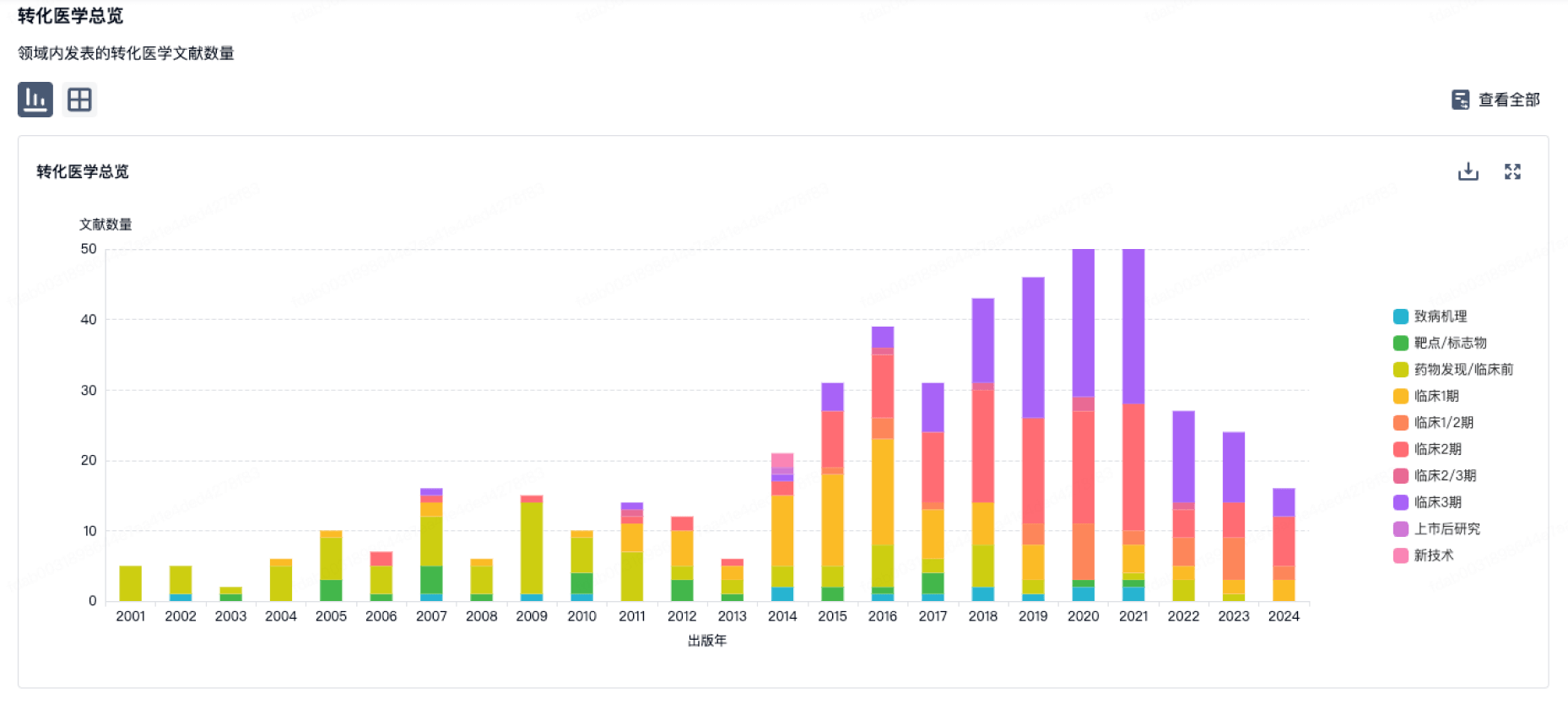

100 项与 Mahzi Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

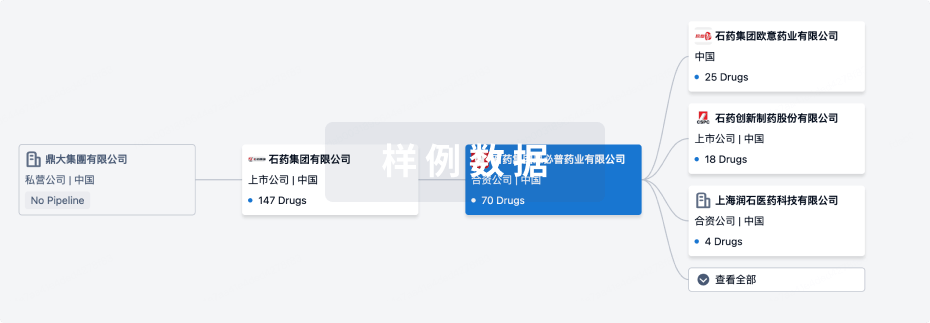

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2025年11月07日管线快照

管线布局中药物为当前组织机构及其子机构作为药物机构进行统计,早期临床1期并入临床1期,临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

临床前

4

登录后查看更多信息

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

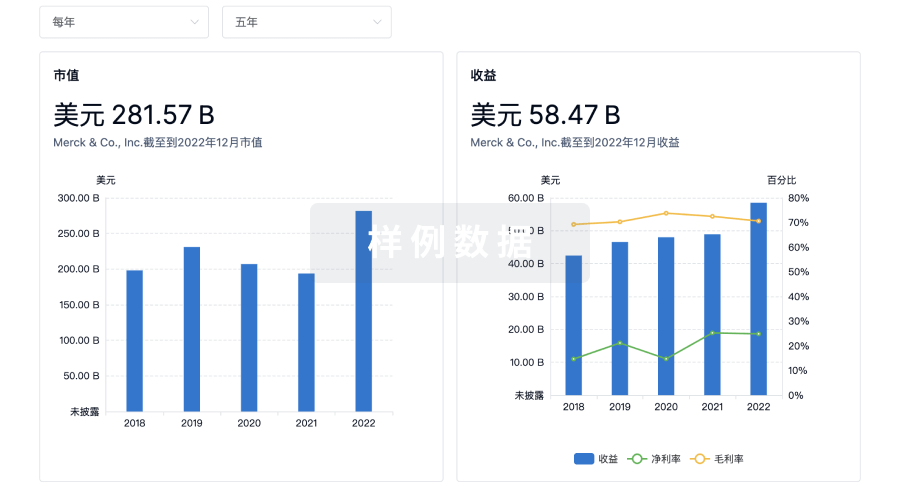

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用