预约演示

更新于:2025-09-09

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

更新于:2025-09-09

概览

标签

呼吸系统疾病

肿瘤

消化系统疾病

小分子化药

疾病领域得分

一眼洞穿机构专注的疾病领域

暂无数据

技术平台

公司药物应用最多的技术

暂无数据

靶点

公司最常开发的靶点

暂无数据

| 排名前五的药物类型 | 数量 |

|---|---|

| 小分子化药 | 3 |

| 排名前五的靶点 | 数量 |

|---|---|

| GDF15(生长分化因子-15) | 1 |

| PARIS(zinc finger protein 746) | 1 |

关联

3

项与 The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences 相关的药物靶点- |

作用机制- |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

靶点 |

作用机制 PARIS inhibitors |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

靶点 |

作用机制 GDF15激动剂 |

原研机构 |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

302

项与 The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences 相关的临床试验NCT06593340

Evaluation of Report-Back Strategies for Long-term and Short-term Exposure Information in Rural Tribal Populations

The goal of this study is to evaluate different ways to provide feedback about environmental sampling results to participants. Specifically, we will look at exposures with long-term risk (radon) and short-term risk (indoor particulate matter, PM2.5). The hypothesis is that providing feedback in real-time will result in participants engaging in more activities to try to reduce their exposure. One of our main questions of interest is: How does the information messenger impact the effectiveness of report-back strategies in rural, tribal populations?

Participants will have radon and PM2.5 measurement equipment installed at their home and will answer questions about any actions they took to reduce exposure. Previously developed approaches to reporting back those exposures will be used to test which feedback method results in more actions to reduce exposure.

Participants will have radon and PM2.5 measurement equipment installed at their home and will answer questions about any actions they took to reduce exposure. Previously developed approaches to reporting back those exposures will be used to test which feedback method results in more actions to reduce exposure.

开始日期2026-10-01 |

申办/合作机构  University of Utah University of Utah [+1] |

NCT06841913

The Effects of Woodsmoke Exposure on Nasal Immune Responses to Influenza Infection in Normal Human Volunteers

This study will investigate the effects of woodsmoke (WS) exposure on human nasal mucosal immune responses to viral infection. The study tests the hypotheses that WS exposure modifies biomarkers of nasal mucosal immune function, increases in Live Attenuated Influenza Virus (LAIV) -induced nasal symptoms, and reduces mucosal antibody production.

开始日期2026-10-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT07111065

Phase II, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Omega-3 Fatty Acid (O3FA) Supplementation for Adult and Juvenile Dermatomyositis (DM/JDM)

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a rare autoimmune disease that causes muscle weakness, skin rashes, and other symptoms. Researchers think both genetic and environmental factors play a role in this disease. They want to find out more about how diet and lifestyle choices affect people with DM/JDM.

Objective:

To see if omega-3 fatty acid supplements from fish oil, combined with a healthy diet, can help people with DM/JDM.

Eligibility:

Adults 18-60 years old, who live in the United States, can read English, and access Internet to complete questionnaires can participate.

Design:

Participants will have 5 or 6 inpatient visits. For 5 visits they may need to stay in the Clinical Center for up to 5 days. Participants will be screened. They will have a physical exam with blood, urine and stool tests. They will have tests of their heart and lung function. Their muscle strength will be measured. They may have an imaging scan of their thighs and pelvis. They will complete online questionnaires about their health and lifestyle. They may complete two optional skin biopsies. Participants will take 4 small capsules by mouth twice a day for up to 6 months. The capsules will contain omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil or a placebo. The placebo looks just like the regular capsule but contains no active ingredients. Participants will not know which capsules they are taking. They will follow a healthy diet based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Participants will receive dietary coaching and will have virtual check-ins throughout the study. For two 7-day periods, they will wear a watch-like device to track their daily activity and sleep patterns. Participants may opt to remain in the study for an additional 12 weeks. All will receive the fish oil supplements during this stage.

Objective:

To see if omega-3 fatty acid supplements from fish oil, combined with a healthy diet, can help people with DM/JDM.

Eligibility:

Adults 18-60 years old, who live in the United States, can read English, and access Internet to complete questionnaires can participate.

Design:

Participants will have 5 or 6 inpatient visits. For 5 visits they may need to stay in the Clinical Center for up to 5 days. Participants will be screened. They will have a physical exam with blood, urine and stool tests. They will have tests of their heart and lung function. Their muscle strength will be measured. They may have an imaging scan of their thighs and pelvis. They will complete online questionnaires about their health and lifestyle. They may complete two optional skin biopsies. Participants will take 4 small capsules by mouth twice a day for up to 6 months. The capsules will contain omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil or a placebo. The placebo looks just like the regular capsule but contains no active ingredients. Participants will not know which capsules they are taking. They will follow a healthy diet based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Participants will receive dietary coaching and will have virtual check-ins throughout the study. For two 7-day periods, they will wear a watch-like device to track their daily activity and sleep patterns. Participants may opt to remain in the study for an additional 12 weeks. All will receive the fish oil supplements during this stage.

开始日期2025-11-03 |

100 项与 The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

8,023

项与 The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences 相关的文献(医药)2025-12-31·CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL HYPERTENSION

L-type calcium channel blockers at therapeutic concentrations are not linked to CRAC channels and heart failure

Article

作者: Parekh, Anant B. ; Padmanabhan, Sandosh ; Mueller, Geoffrey ; Tucker, Charles J. ; Lin, Yu-Ping ; Shi, Min ; Bird, Gary S.

Amlodipine has been used as a front-line anti-hypertensive therapy for decades by virtue of blocking voltage-operated calcium channels with high affinity and specificity. Recently, the safety of amlodipine has been questioned, as it was reported to activate Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels and increase the risk of heart failure. Here we show, using a variety of approaches, that amlodipine does not activate CRAC channels at therapeutic concentrations. Combined with our previous meta-analysis, our study should reassure physicians that amlodipine should continue to be prescribed for treating hypertension.

2025-12-15·RAPID COMMUNICATIONS IN MASS SPECTROMETRY

Open‐Source System Suitability: Mass Spectrometry Query Language Lab (MassQLab)

Article

作者: Jarmusch, Alan K. ; Johnson, Dylan ; Winter, Heather L.

ABSTRACT:

Rationale:

Reproducible analytical instrumentation system performance is critical for mass spectrometry, particularly metabolomics, aptly named system suitability testing. We identified a need based on literature reports that stated only 2% of papers performed system suitability testing.

Methods:

We report MassQLab, built upon open‐source, vendor‐agnostic software called the mass spectrometry query language (MassQL). MassQL, implemented in MassQLab, provides freedom for researchers to choose their analyte/s, mass spectrometry system (including liquid chromatography—mass spectrometry), and metrics of performance.

Results:

In this report, we describe the use of MassQLab, demonstrate the construction of the required MassQL query, common metrics of performance (i.e., extracted ion chromatograms), uncommon metrics (i.e., MS/MS product ion spectra), and discuss insights gained about performance—including issues requiring correction prior to sample analysis.

Conclusions:

MassQLab is a flexible solution for system suitability testing for mass spectrometry‐based analytical measurements. Deficits in analytical performance, while unavoidable and rare, were noted prior to data collection and corrected. The open‐source and adaptable nature of MassQLab will empower researchers and lead to improved implementation of system suitability testing.

2025-11-01·FREE RADICAL BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE

Macrophage NADPH oxidase inhibition by ultralow-dose dextromethorphan alleviates DSS-induced inflammation and colitis

Article

作者: He, Guangbo ; Hong, Jau-Shyong ; Hou, Lijingzhe ; Li, Yuqian ; Guo, Yanjie ; Cheng, Kang ; Li, Sheng ; Zhao, Jie

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, is a chronic inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract with limited treatment options and no definitive cure. Emerging evidence implicates NADPH oxidase (Nox) in IBD pathogenesis, but the specific subtype involved and its therapeutic potential remain unclear. To assess the efficacy of dextromethorphan (DM), a potent Nox2 inhibitor, we employed a dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced chronic colitis model in mice. Mice exposed to intermittent DSS for 34 days developed IBD-like symptoms, including weight loss, elevated disease activity index (DAI), colon shortening, and epithelial barrier disruption. DM exhibited a bimodal protective effect: both standard-dose DM (10 mg/kg/day) and ultralow-dose DM (ULDM, 10 ng/kg/day) significantly reduced colitis severity, with ULDM proving more effective and selected for further studies. Notably, ULDM remained effective when post-administered after DSS exposure. Histological analyses revealed that ULDM reduced immune cell infiltration, crypt damage, and tissue disruption. It also suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (MCP-1, IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) and oxidative stress markers (myeloperoxidase, malondialdehyde, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine), while enhancing anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10) and antioxidant enzymes (catalase, superoxide dismutase). Importantly, ULDM protected Nox1 KO but not Nox2 KO mice, indicating a Nox2-dependent mechanism. In vitro, ULDM inhibited Nox2 activation in primary macrophages and RAW 264.7 cells by blocking the membrane translocation of p47phox. Furthermore, our study suggested a feed-forward inflammatory cycle between epithelial cell death and macrophage overactivation that exacerbated colitis. Together, these findings demonstrated that Nox2 played a central role in DSS-induced chronic colitis and identified ultralow-dose dextromethorphan as a promising, mechanism-based therapeutic candidate for IBD.

67

项与 The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences 相关的新闻(医药)2025-04-23

New findings in Nature reveal how age-related gut changes fuel the growth of pre-leukemic blood cells and may increase other disease risks

CINCINNATI, April 23, 2025 /PRNewswire/ -- Scientists at Cincinnati Children's along with an international team of researchers have discovered a surprising new connection between gut health and blood cancer risk—one that could transform how we think about aging, inflammation, and the early stages of leukemia.

Continue Reading

The left image shows tiny signaling structures called TIFAsomes (red) forming in blood cells when cultured with the plasma of a healthy 73-year-old, but not when cultured with the plasma of a healthy 31-year-old (right). A study in Nature led by cancer experts at Cincinnati Children’s reports that these aging-related TIFAsomes can be activated by a bacterial byproduct that can escape from the gut into the bloodstream and fuel the expansion of pre-leukemia cells.

As we grow older—or in some cases, when gut health is compromised by disease—changes in the intestinal lining allow certain bacteria to leak their byproducts into the bloodstream. One such molecule, produced by specific bacteria, acts as a signal that accelerates the expansion of dormant, pre-leukemic blood cells, a critical step to developing full-blown leukemia.

The team's findings—published April 23, 2025, in the journal Nature—lay out for the first time how this process works. The study also suggests that this mechanism may reach beyond leukemia to influence risk for other diseases and among older people who share a little-known condition called clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP).

"This study significantly advances our understanding about how blood cancers develop and progress, especially in older adults. The exciting news is that we also may have a way to intervene early—before these pre-leukemic cells evolve into more aggressive disease. We look forward to conducting further studies to pursue this new approach," says Daniel Starczynowski, PhD, director of the Advanced Leukemia Therapies and Research Center at Cincinnati Children's and corresponding author for the new study.

"Our research shows age-associated changes in the gut to be a non-traditional risk factor in the development of blood cancers. Thus, taking care of your gut could be more important than ever," says Puneet Agarwal, PhD, an associate staff scientist with the Division of Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology, and first author on the study.

Leukemia, aging and the gut

More than 470,000 Americans are living with leukemias and more than 62,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. Of these people, nearly 24,000 were projected to die of their disease in 2024, according to the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program.

While survival rates for leukemia have improved over the years, it remains a life-threatening cancer that disproportionately affects people over 65. Scientists have long wondered why age is such a dominant risk factor. Now Starczynowski and colleagues may have found a compelling answer.

A disease risk cascade traced to a bacteria-made sugar

As we age, the gut lining becomes more permeable, thus allowing more interactions between the contents of the intestine and the blood system. Inside the intestine, a variety of common "gram-negative" bacteria tend to multiply in older people, producing rising amounts of a bacterial sugar called ADP-heptose. Turns out, this bacterial byproduct can cause problems when it gets into the bloodstream.

"ADP-heptose is uniquely found in the circulation of older individuals and favors the expansion of pre-leukemic cells," Starczynowski says. "This sugar also is found in younger individuals that have experienced disruption of their gut."

This study involved a host of complex experiments to decipher the mechanisms involved that allow ADP-heptose to act like pre-leukemia fuel. Importantly, the team found tiny signaling structures called TIFAsomes forming inside the cells, which indicates that ADP-heptose can activate expansion of pre-leukemic blood cells.

In fact, the team developed a TIFAsome Assay, a new blood test to detect ADP-heptose activity in circulation. This tool is now available to other researchers. Click here for more information.

Once the process could be measured, the research team could see potentially far-reaching implications.

What is CHIP?

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) describes a condition in which a person's blood cells gradually acquire mutations that set the stage for diseases to develop. These mutated cells then make multiple copies – or clones. Some of these mutations are well-known to be linked to blood cancers. But others are associated with other illnesses, including heart disease, stroke, and inflammatory conditions.

An estimated 10–20% of adults over 70 have CHIP, yet few know it because there are no symptoms and routine screenings don't yet exist.

In the new study, researchers generated mice that mimic CHIP. In these mice, the early-stage pre-leukemic cells dramatically expanded when exposed to ADP-heptose from the gut bacteria.

"This is a perfect storm of risk factors: age-related changes in gut microbiota and intestinal permeability, exposure to ADP-heptose, and the presence of pre-leukemic cells. Together, they create an environment that supports the expansion of the harmful pre-leukemic cells," Starczynowski says.

A potential way to block the process

While studying affected blood cells, the Cincinnati Children's research team determined that the ability of ADP-heptose to trigger pre-leukemia cell expansion depends directly upon a receptor protein found in mutant blood cells called ALPK1.

In theory, blocking the function of that receptor could prevent the CHIP condition from developing into leukemia and contributing to other related chronic illnesses. Currently, however, no drug compound exists for inhibiting ALPK1.

The research team explored several possible strategies to disrupt the ALPK1 pathway. They reported finding one difference-making candidate: an enzyme produced by the gene UBE2N. When pre-leukemic cells were treated with the UBE2N inhibitor, their expansion was significantly hampered—even in the presence of ADP-heptose.

Much more research is needed to explore how to convert these mouse-based findings into a method for preventing leukemia in humans.

"One of our goals is to develop an ALPK1 inhibitor that can be used in humans. These findings provide promising insights that will help us move forward," Starczynowski says.

Implications beyond leukemia

An emerging collection of studies suggests that CHIP may also contribute to other age-associated conditions, including cardiovascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis, gout and osteoporosis. These findings underscore the gut microbiota's role as a gatekeeper for systemic health.

"CHIP is emerging as a major public health concern," Starczynowski says. "More than 10 million older adults may have CHIP without knowing it. Our study suggests that preserving gut health might be a powerful strategy to prevent blood disorders and potentially other age-related diseases."

How might individuals reduce their own risk?

It will take years to produce new medications based on discovering this connection between gut health and leukemia risk. In the meantime, many seniors may wonder what they can do to minimize their risk of developing CHIP?

It might be possible to better manage gut health via dietary adjustments or by using pre- or pro-biotics. Much research suggests that the composition and function of gut microbiota can be manipulated.

But for addressing CHIP, the correct dietary changes and accurate, effective pro-biotics have not been determined, Starczynowski says.

About the study

Cincinnati Children's co-authors included Avery Sampson, Kathleen Hueneman, Kwangmin Choi, Emma Uible, Chiharu Ishikawa, Jennifer Yeung, and Lyndsey Bolanos, all with the Division of Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology; Xueheng Zhao and Kenneth Setchell with the Division of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine; and David Haslam, Division of Infectious Diseases. Experts at the University of Cincinnati, University of Oxford, and Texas A&M University also contributed.

Funding sources for this work included grants from the National Institutes of Health (U54DK126108, R35HL135787, R01CA275007), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (T32ES007250), Cincinnati Children's Hospital Research Foundation, Edwards P. Evans Foundation, and Cancer Free Kids.

This work was supported by several shared research facilities at Cincinnati Children's including the Comprehensive Rodent and Radiation Facility, the Viral Vector Facility, Research Flow Cytometry Facility, the NMR-based Metabolomics Facility, and the DNA Genomics Sequencing Facility.

Starczynowski has disclosed that he serves on the scientific advisory board at Kurome Therapeutics and has equity in the company.

SOURCE Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

2025-01-07

TUESDAY, Jan. 7, 2025 --

Fluoride

exposure appears to slightly decrease IQ scores in children, a new federal

meta-analysis

has concluded -- but not at the low levels recommended for U.S. drinking water.

Fluoride in drinking water was associated with reduced IQ scores at levels of less than 4 milligrams per liter, but not at less than 1.5 mg/L, according to the analysis by researchers at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

The recommended level of fluoride in U.S. drinking water is 0.7 mg/L, the U.S. Public Health Service says.

“There were limited data and uncertainty in the dose-response association between fluoride exposure and children’s IQ when fluoride exposure was estimated by drinking water alone at concentrations less than 1.5 mg/L,” concluded the research team led by

Kyla Taylor

, a health scientist with the NIEHS’ Division of Translational Toxicology.

Researchers found a 1.14-point decrease in IQ score for every 1 mg/L increase in fluoride found in urine, when restricting their analysis to the 11 most trustworthy studies included in the evidence review.

The new evidence review appears in the prestigious journal

JAMA Pediatrics

, and comes at a time when fluoridation is taking political heat. Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the nominee to lead the Department of Health and Human Services, is an outspoken critic of fluoridation.

Fluoride is added to drinking water to protect against

tooth decay

, a practice supported by groups like the American Dental Association.

Critics of the new review noted that none of the 74 studies included in the review took place in the United States. Most were conducted in China (45), with others taking place in India (12), Mexico (4), Iran (4), Canada (3) and Pakistan (2).

“The public needs to understand that the levels examined in (the) report are from countries with high levels of naturally occurring fluoride that is more than double the amount recommended by the U.S. Public Health Service to optimally fluoridate community water systems and help prevent dental disease,”

Dr. Brett Kessler

, president of the American Dental Association, said in a

news release

.

For the study, the federal researchers sorted available studies on fluoridation based on their risk of bias. Of the studies, 52 were rated high risk of bias and 22 low risk of bias.

In 31 studies looking at fluoride in drinking water, exposure appeared to lower IQ at levels less than 4 mg/L and less than 2 mg/L, but not less than 1.5 mg/L.

Another 20 studies that measured fluoride levels in urine found lowered IQ at less than 4 mg/L, less than 2 mg/L, and less than 1.5 mg/L, researchers said.

The research team noted that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) can take action against a public water source if fluoride levels reach 4 mg/L, and can issue warnings at 2 mg/L.

“To our knowledge, no studies of fluoride exposure and children’s IQ have been performed in the United States, and no nationally representative urinary fluoride levels are available, hindering application of these findings to the US population,” the NIEHS team concluded in its paper.

“Although this meta-analysis was not designed to address the broader public health implications of water fluoridation in the United States, these results may inform future public health risk-benefit assessments of fluoride,” the team added.

In an accompanying

editorial

in

JAMA Pediatrics

, public health dentist

Dr. Steven Levy

criticized the evidence review and urged caution in interpreting its findings – particularly when it came to findings based on fluoride found in urine.

"There is scientific consensus that the urinary sample collection approaches used in almost all included studies (ie, spot urinary fluoride or a few 24-hour samples, many not adjusted for dilution) are not valid measures of individuals’ long-term fluoride exposure, since fluoride has a short half-life and there is substantial variation within days and from day to day," wrote Levy, a professor of research at the University of Iowa College of Dentistry and Dental Clinics.

JAMA Pediatrics

also ran a second editorial praising the evidence review.

“What this meta-analysis does is it has a way of synthesizing all of that information, not letting one study drive or five studies drive the results,” editorial co-author

Bruce Lanphear

, a professor of health sciences at Simon Fraser University, told STAT.

The study shows “not definitive, but sufficient” evidence of fluoride as a neurotoxicant to warrant “an urgent response by federal agencies like the EPA that regulates the amount of fluoride in water,” added Lanphear, who has also served as an expert witness in a lawsuit against the EPA regarding fluoridation.

The American Dental Association continued to stand by its support for fluoride in a statement responding to the federal report.

“To prevent dental disease the ADA continues to recommend drinking optimally fluoridated water along with twice daily brushing with fluoride toothpaste and eating a healthy diet, low in added sugars,” Kessler said in the statement.

Whatever your topic of interest,

subscribe to our newsletters

to get the best of Drugs.com in your inbox.

临床结果

2024-08-07

ATLANTA, Aug. 7, 2024 /PRNewswire/ -- Continuing in its major efforts to transform PCOS care and empower stakeholders, PCOS Challenge: The National Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Association has organized the largest PCOS Awareness Month to date for this September with nearly 1,000 partners and over 400 lighting events in 33 countries. "Voice of Strength, Agents of Change" is the 2024 PCOS Awareness Month theme. The September events and campaign are set to galvanize patients, healthcare providers, researchers, policymakers, and industry leaders to join forces in addressing the urgent needs of the PCOS community.

Continue Reading

PCOS Challenge Mobilizes Global Community for 2024 Awareness Month with Over 400 Landmark Lightings and National Tour

PCOS Challenge Mobilizes Global Community for 2024 Awareness Month with Over 400 Landmark Lightings and National Tour

"Voice of Strength, Agents of Change" underscores the power of collective action in transforming PCOS care. This theme invites stakeholders to share personal stories, support patient-centered research, and contribute to initiatives that address the unmet needs of patients. Collaborative efforts will focus on amplifying stakeholder voices to initiate impactful changes across healthcare, including accelerating the development of new PCOS-specific treatments and empowering all stakeholders to co-create healthcare solutions with patients.

"It is an honor to be able to create opportunities for all PCOS stakeholders including patients, clinicians, researchers, and government agencies to learn and engage around PCOS awareness. PCOS is the most common hormone condition and a leading cause of infertility in women. It can have severe quality-of-life impacts, and lead to lifelong complications and other serious health conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, mental and maternal health complications and cancer," says Sasha Ottey, Founder and Executive Director of PCOS Challenge. "With an economic burden exceeding $15 billion a year in the U.S. alone and 50-70% of people with the condition going undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, it is crucial that we increase awareness, resources and innovations for improving PCOS outcomes. This year's theme, 'Voice of Strength, Agents of Change,' reflects our commitment to amplifying patient voices, closing gaps in care, and driving meaningful change."

The 2024 PCOS Awareness Month will kick off with the Seventh Annual World PCOS Day of Unity on Sunday, September 1st. Starting on World PCOS Day, hundreds of landmarks will illuminate teal at various points throughout the month, symbolizing global solidarity and awareness for PCOS."It is truly incredible to see the growth of PCOS awareness and PCOS Awareness Month over the last decade. It's inspiring to see many global leaders recognizing the seriousness of PCOS, shining a light on this important cause, supporting their communities, and engaging with us to bring change," says Ashley Levison, @PCOSGurl, the Patient Advisory Board Member who coordinated all the lighting events for PCOS Challenge. Ashley is the recipient of the PCOS Challenge Advocacy Lifetime Achievement Award.Each week of PCOS Awareness Month has a specific focus:

Week 1: PCOS Support and Advocacy (Sep. 1–7)

Week 2: Fertility, Family Building, and Pregnancy and Maternal Health (Sep. 8-14)

Week 3: Lifestyle Management for PCOS (Sep. 15-21)

Week 4: PCOS Related Disorders (Sep. 22-28)

Week 5: Adolescent Health (Sep. 29-30)

Throughout the month, PCOS Challenge will host multiple events bringing together patients, researchers, healthcare providers, industry leaders, and others to educate the global community about PCOS and promote the need for timely diagnosis and improved care. Key events include a workshop titled, "Advancing PCOS Research and Care: Innovations in Cardiometabolic Health and AI-Driven Diagnostics," featuring speakers from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS).Additionally, PCOS Challenge will launch a national PCOS Tour of PCOS centers and clinics across the country to highlight advances in PCOS care and connect patients with expert resources.PCOS Challenge thanks its partners and sponsors for their support in making this year's awareness month impactful.For more information about PCOS Awareness Month, PCOS Challenge, sponsorship opportunities, lighting events, the social media toolkit, or to schedule media interviews, please visit PCOSAwarenessMonth.org and PCOSChallenge.org.

About PCOS Challenge: The National Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Association

Serving nearly 60,000 members, PCOS Challenge is the largest support and advocacy organization for people with PCOS. PCOS Challenge is the sponsoring organization for World PCOS Day and PCOS Awareness Month and offers supporting resources, information, and events.

Media Contact:

William Patterson

Director of Public Affairs

PCOS Challenge: The National Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Association

Telephone: 404-855-7244

SOURCE PCOS Challenge: The National Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Association

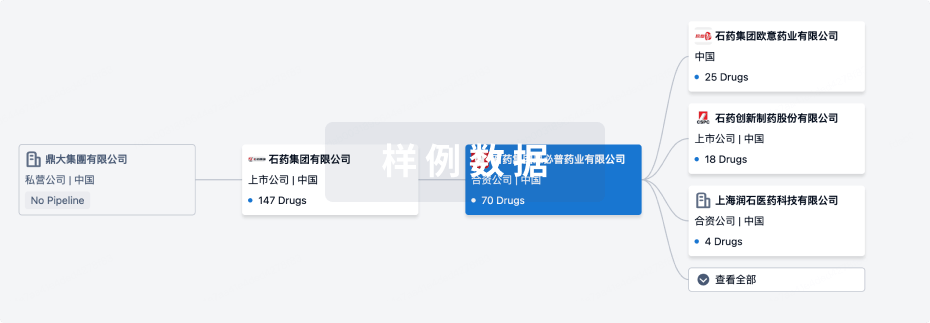

100 项与 The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

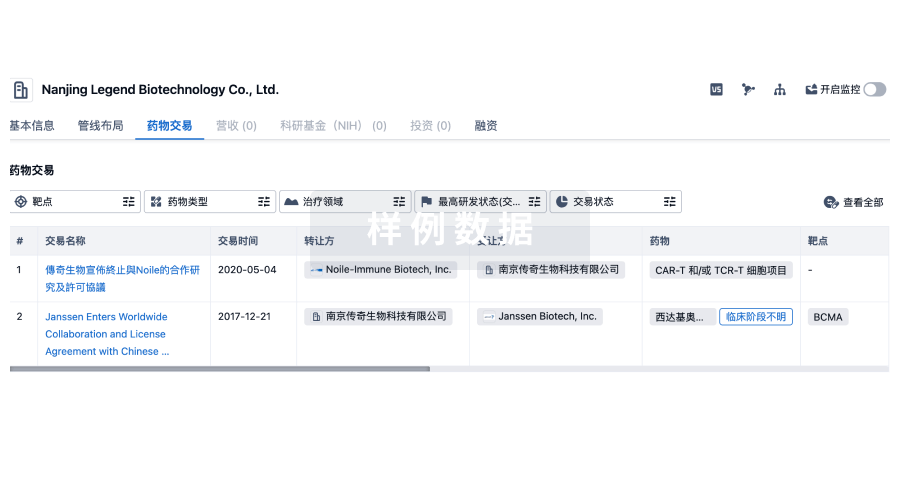

100 项与 The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

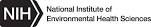

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2025年11月01日管线快照

管线布局中药物为当前组织机构及其子机构作为药物机构进行统计,早期临床1期并入临床1期,临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

临床前

3

登录后查看更多信息

当前项目

| 药物(靶点) | 适应症 | 全球最高研发状态 |

|---|---|---|

TFF-HMW-HA | 慢性阻塞性肺疾病 更多 | 临床前 |

Caffeic acid phenethyl ester ( GDF15 ) | 结直肠癌 更多 | 临床前 |

法呢醇 ( PARIS ) | 肺癌 更多 | 临床前 |

登录后查看更多信息

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

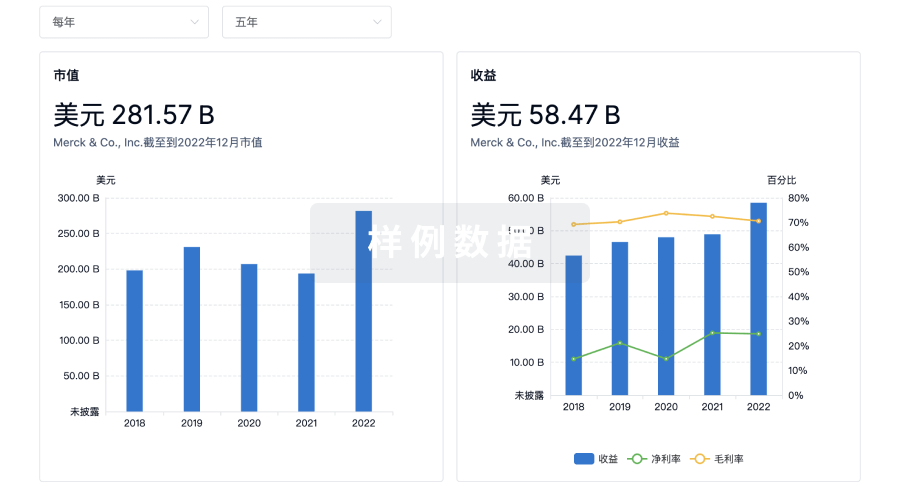

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

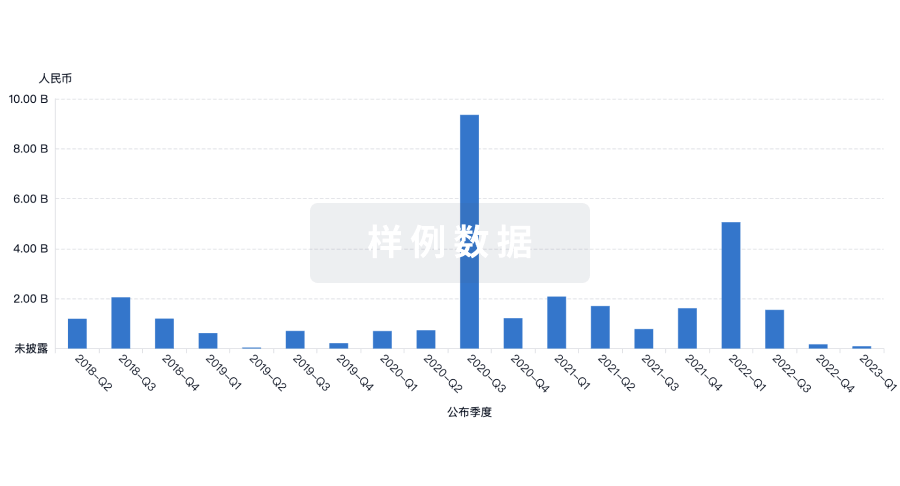

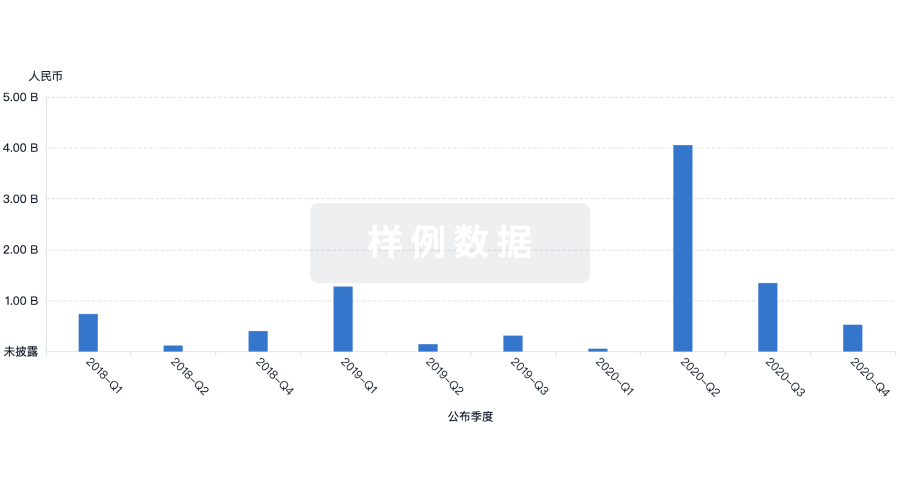

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用