预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

Scorpion Therapeutics, Inc.

更新于:2025-05-07

概览

标签

肿瘤

呼吸系统疾病

消化系统疾病

小分子化药

关联

3

项与 Scorpion Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的药物作用机制 EGFR exon 20抑制剂 [+1] |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床1/2期 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

作用机制 EGFR19外显子缺失突变抑制剂 [+1] |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床1/2期 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

作用机制 PIK3CA H1047R 抑制剂 [+1] |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床1/2期 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

2

项与 Scorpion Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的临床试验NCT06901336

An Open-Label Phase 1 Study in Healthy Male Subjects to Investigate the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion of [14C]-STX-478 Following Single-Dose Oral Administration

The main purpose of this study is to conduct blood tests to measure how much STX-478 is in the bloodstream and how the body handles and eliminates it in healthy participants. This study will involve a single dose of 14C radiolabeled STX-478. This means that a radioactive tracer substance, C14, will be incorporated into the study drug STX-478 to investigate the study drug and its breakdown products and to find out how much of these passes from blood into urine, feces and expired air. The study will also evaluate the safety and tolerability of STX-478.

开始日期2025-03-20 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT05768139

First-in-Human Study of STX-478, a Mutant-Selective PI3Kα Inhibitor as Monotherapy and in Combination With Other Antineoplastic Agents in Participants With Advanced Solid Tumors

Study STX-478-101 is a multipart, open-label, phase 1/2 study evaluating the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics (PK), and preliminary antitumor activity of STX-478 in participants with advanced solid tumors with P13Ka mutations.

Part 1 will evaluate STX-478 as monotherapy in participants with advanced solid tumors. Part 2 will evaluate STX-478 therapy as combination therapy with fulvestrant in participants with hormone receptor positive (HR+) breast cancer. Part 3 will evaluate STX-478 as combination therapy with fulvestrant and a CDK4/6 Inhibitor (either Ribociclib or Palbociclib) in participants with HR+ breast cancer.

Each study part will include a 28-day screening period, followed by treatment with STX-478 monotherapy or combination therapy.

Part 1 will evaluate STX-478 as monotherapy in participants with advanced solid tumors. Part 2 will evaluate STX-478 therapy as combination therapy with fulvestrant in participants with hormone receptor positive (HR+) breast cancer. Part 3 will evaluate STX-478 as combination therapy with fulvestrant and a CDK4/6 Inhibitor (either Ribociclib or Palbociclib) in participants with HR+ breast cancer.

Each study part will include a 28-day screening period, followed by treatment with STX-478 monotherapy or combination therapy.

开始日期2023-04-17 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 Scorpion Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 Scorpion Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

8

项与 Scorpion Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的文献(医药)2025-02-13·Journal of Medicinal Chemistry

Discovery of STX-721, a Covalent, Potent, and Highly Mutant-Selective EGFR/HER2 Exon20 Insertion Inhibitor for the Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Article

作者: Jackson, Erica L. ; Ronseaux, Sébastien ; Pagliarini, Raymond A. ; Stuart, Darrin D. ; O’Hearn, Erin L. ; Brooijmans, Natasja ; Guzman-Perez, Angel ; Jonsson, Philip ; Huff, Michael R. ; Ito, Takahiro ; Roberts, Simon A. ; Henderson, Jack A. ; Milgram, Benjamin C. ; Wang, Weixue ; Ladd, Brendon ; Borrelli, Deanna R. ; Hilbert, Brendan J.

2024-05-02·Cancer Research

Abstract PO2-18-04: STX-478 is a potentially best-in-class mutant-selective PI3Kα inhibitor that demonstrates robust efficacy in ER+ breast cancer models as monotherapy and in combination with standard of care agents

作者: Buckbinder, Leonard ; Dowdell, Gregory ; Jackson, Erica ; Manimala, Samantha ; Alltucker, Jacob ; Tieu, Trang ; Stuart, Darrin ; Huff, Michael ; Guzman-Perez, Angel ; Jean, David St.

2024-05-02·Cancer Research

Abstract PO1-20-04: STX-478-101: A phase 1/2, first-in-human study of STX-478 monotherapy or in combination with fulvestrant in patients with breast cancer or other advanced solid tumors (trial in progress)

作者: Montero, Alberto ; Roberts, Simon ; Ewert, Courtney ; Pluard, Timothy ; Streit, Michael ; Patterson, Monica ; Orr, Douglas ; Juric, Dejan ; LoRusso, Patricia ; Winer, Ira ; Munster, Pamela ; Corsi-Travali, Stefani ; Jhaveri, Komal

171

项与 Scorpion Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的新闻(医药)2025-05-02

·抗体圈

在医药行业的激烈竞争中,礼来公司(Eli Lilly and Company)凭借两款明星产品实现了业绩的飞跃式增长。2025 年第一季度财报显示,礼来的营收大幅增长 45%,这一亮眼成绩背后,Zepbound 和 Mounjaro 两款药物功不可没。营收业绩亮眼,明星产品驱动增长礼来公司第一季度的表现堪称惊艳,总营收达到 127.3 亿美元 ,同比增长 45%。首席执行官大卫・里克斯(David Ricks)在财报电话会议上虽低调表示这是 “稳健的开局”,但实际成绩远超预期。本季度礼来的每股收益同比增长 23%,达到 3.06 美元,高于分析师预期的 2.68 美元 。推动营收增长的核心动力来自糖尿病药物 Mounjaro 和减肥药物 Zepbound。Mounjaro 本季度销售额达 38.4 亿美元,相较于 2024 年同期的 18.1 亿美元,增长了 113%;Zepbound 销售额为 23.1 亿美元,而 2024 年第一季度其刚上市时仅为 5.17 亿美元 。这两款药物含有相同的活性成分替尔泊肽(tirzepatide),强劲的销售表现使得 Leerink Partners 此前预计的两款药物本季度全球销售额为 59 亿美元,而实际二者合计达到 61.5 亿美元 。国内外市场差异显著,各有增长亮点从市场区域来看,礼来在美国市场和国际市场呈现出不同但均积极的增长态势。美国市场增长尤为强劲,营收同比增长 49%,达到 84.9 亿美元 。这主要得益于 Mounjaro 和 Zepbound 的热销。不过,礼来也指出,较低的实际价格导致营收减少了 7% ,一定程度上抵消了增长带来的收益。在国际市场,礼来的营收增长了 38%,达到 42.4 亿美元 。Mounjaro 成为增长的主要驱动力,由于 Zepbound 在海外市场尚未广泛上市,在部分地区礼来将这款减肥药物以 Mounjaro 的名义进行销售 。此外,礼来的上一代糖尿病药物 Jardiance 也在一定程度上助力了国际市场的营收增长。加大研发投入,着眼未来发展为了保持增长的动力和可持续性,礼来在研发方面持续发力。本季度,公司将研发投入提高了 8%,达到 27.3 亿美元,占营收的比例超过 21% 。根据财报发布的信息,这些资金被投入到早期和后期的研发项目组合中,旨在进一步丰富产品线,为未来的发展奠定坚实基础。尽管本季度因收购 Scorpion Therapeutics 的 PI3Kα 抑制剂 STX - 478 产生了 15.7 亿美元的研发减值费用(该收购项目礼来前期支付了 10 亿美元,总潜在交易价值为 25 亿美元 ),但这并未影响公司对研发的重视和投入。礼来公司凭借 Zepbound 和 Mounjaro 在市场上的出色表现,实现了营收的大幅增长,同时通过加大研发投入为未来布局。在竞争激烈的医药市场中,礼来能否继续凭借这两款明星产品保持优势,新的研发项目又能否带来更多的增长机遇,行业正拭目以待。参考来源:https://www.biospace.com/business/lillys-revenue-leaps-45-thanks-to-zepbound-mounjaro-of-course识别微信二维码,添加抗体圈小编,符合条件者即可加入抗体圈微信群!请注明:姓名+研究方向!本公众号所有转载文章系出于传递更多信息之目的,且明确注明来源和作者,不希望被转载的媒体或个人可与我们联系(cbplib@163.com),我们将立即进行删除处理。所有文章仅代表作者观点,不代表本站立场。

财报并购

2025-05-02

·药时代

正文共: 3950字 12图预计阅读时间: 8分钟2025年前四个月,全球医药行业迎来了一波交易热潮。根据不完全统计数据,跨国药企共达成38笔重大交易,总金额高达596亿美元。这些交易涵盖了并购(M&A)和许可(licensing)等多种形式,涉及肿瘤、代谢、免疫与炎症(I&I)、罕见病等多个治疗领域。值得注意的是,中国药企在其中的表现尤为亮眼,成为推动全球医药创新的重要力量。01MNC还是主要买买买!从2025年跨国药企(MNC)的交易情况来看,交易总数达到了38笔,其中以授权引进(In-licensing)交易最为频繁,共计28笔,占比高达73.68%,这表明跨国药企在积极寻求外部创新资源,通过合作加速研发管线的拓展。并购(M&A)交易有8笔,占比21.05%,显示出部分企业通过收购来实现快速的战略布局和资源整合。总结一句话,就是:MNC还是主要买买买,无论是买产品,还是买公司。授权输出(Out-licensing)交易则有2笔,占比5.26%,反映了跨国药企在特定领域寻求合作伙伴以优化资源配置和市场拓展的策略。这两笔对外授权(Out-licensing)交易的卖方均为罗氏。这和罗氏最近一段时间内剥离资产而战略优化管线,聚焦核心领域的工作密切相关。这一策略与罗氏同期引进Zealand Pharma的GLP-1药物Petrelintide(代谢)和信达生物的DLL3-ADC(肿瘤)形成对比,显示其倾向高潜力、临近商业化的领域。通过“引进+剥离”,罗氏正强化在肿瘤、代谢及中枢神经系统的领先地位,同时减少早期项目的资源分散。未来,该公司或继续以类似方式优化管线,平衡创新与效率。【推荐阅读】罗氏砍掉十条管线?彻底放弃TIGIT?罗氏停止多项乙肝新药管线!关于并购,8笔重大并购交易总金额超过266亿美元,涉及肿瘤、代谢疾病、精神健康等核心治疗领域,反映出跨国药企通过并购加速管线扩充和市场占位的战略趋势。肿瘤领域仍是并购核心,共4笔交易,占比50%。其中,强生(Johnson & Johnson)以146亿美元收购Intra-Cellular Therapies,获得精神分裂症药物Caplyta,虽非肿瘤资产,但创下年内最高交易额;而礼来(Eli Lilly)以25亿美元收购Scorpion Therapeutics,获得PI3Kα抑制剂STX-478,强化其肿瘤靶向治疗布局。此外,德国默克(Merck)以45.8亿美元收购Springworks Therapeutics,获得γ-分泌酶抑制剂Ogsiveo(已上市),补充其罕见病与肿瘤管线。整体来看,跨国药企在2025年的交易活动呈现出多元化和积极主动的特点,旨在通过不同形式的合作与整合,提升自身在全球医药市场的竞争力和创新能力。02交易排行榜交易排行榜分为总金额排行榜和交易数排行榜。交易总金额方面,38笔交易中有32笔披露了总金额,6笔选择不披露。总金额最高为146亿美元,最低1700万美元。排行榜的前十名分别是:强生(Johnson & Johnson)收购Intra-Cellular Therapies:交易金额高达146亿美元,涉及已上市药物Caplyta,靶点为5-HT2R和D2R,精神科领域。Eli Lilly收购Scorpion Therapeutics:交易金额为25亿美元,涉及处于1/2期临床的STX-478,靶点为PI3Ka,肿瘤领域。Novartis收购Anthos Therapeutics:交易金额为30.75亿美元,涉及处于3期临床的Abelacimab,靶点为FXI和FXla,心血管领域。AstraZeneca授权引进Syneron Bio:交易金额为34.75亿美元,涉及处于临床前阶段的未披露药物,代谢和免疫炎症(I&I)领域。Roche授权引进Zealand Pharma:交易金额为52.5亿美元,涉及处于2b期临床的Petrelintide,靶点为GLP-1,代谢性疾病。Merck收购Springworks:交易金额为39亿美元,涉及已上市药物Ogsiveo,靶点为Y-secretase,罕见病领域。Novo Nordisk授权引进The United Laboratories:交易金额为20亿美元,涉及处于1期临床的UBT251,靶点为GLP-1R、GCGR和GIPR,代谢性疾病。Abbvie授权引进Xilio Therapeutics:交易金额为21.52亿美元,涉及处于临床前阶段的多款药物,靶点为生物及三特异性抗体,肿瘤领域。Eli Lilly授权引进Magnet Biomedicine:交易金额为12.9亿美元,涉及处于发现阶段的未披露药物,肿瘤领域。Merck & Co.授权引进Hengrui Pharma:交易金额为19.7亿美元,涉及处于2期临床的HRS-5346,靶点为Lp(a),代谢性疾病。交易数方面,参与交易数目较高的药企包括:Eli Lilly(礼来)共完成5笔交易,Abbvie(艾伯维)、Merck(德国默克)和Roche(罗氏)各完成了4笔交易,Novo Nordisk(诺和诺德)和Sanofi(赛诺菲)分别完成了3笔交易,AstraZeneca(阿斯利康)和Bayer(拜耳)各完成了2笔交易,Johnson & Johnson(强生)和GSK(葛兰素史克)分别完成了2笔和1笔交易。这些数据表明,2025年跨国药企在交易市场上表现活跃,通过多种合作形式积极拓展研发管线、优化资源配置,并在全球市场中寻求新的增长机会。03交易时产品所处开发阶段交易时产品所处的阶段是中国公司非常关心的一个细节。2025年跨国药企交易中,产品所处的开发阶段主要集中在临床前和Phase 1阶段,这两个阶段的交易数量占据了较大比例。具体来看,临床前阶段的交易数量最多,共有11笔,占比约为28.9%,显示出药企在早期研发阶段的活跃度,以及对创新药物潜力的重视。紧随其后的是Phase 1阶段,共有10笔交易,占比约为26.3%,这表明药企在药物进入临床试验初期就积极寻求合作,以加速研发进程。此外,已上市(Marketed)和发现(Discovery)阶段的交易数量也相对较多,分别为5笔和3笔,这反映了药企对成熟产品和早期创新项目的关注。Phase 3阶段的交易数量为3笔,占比约为7.9%,而其他阶段如Phase 2、Phase 2b、Phase1/2等的交易数量则相对较少,均在1-2笔之间。整体来看,药企在交易时更倾向于早期阶段的产品,这可能是为了在药物研发的早期阶段就进行战略布局,以获取潜在的高回报。04药物类型2025年跨国药企交易中药物类型的分布情况显示,小分子药物(small molecule)占据了主导地位,共有21笔交易,占比高达55.3%,这反映了小分子药物在药物研发和治疗应用中的广泛性和灵活性。肽类药物(peptide)以4笔交易位居第二,占比10.5%,显示出在特定治疗领域如代谢和肿瘤治疗中的重要性。双抗(bsAb)、单抗(mAb)、三抗各有4笔、2笔、2笔交易,这表明抗体类药物在治疗领域的持续创新和应用潜力。此外,抗体药物偶联物(ADC)也占据了一定的市场份额,有2笔交易,占比5.3%,这和ADC因在肿瘤治疗中的显著疗效而连年火热有关。药时代团队计划近日发布文章,《过去5年里中国ADC新药出海交易汇总分析》,欢迎感兴趣的朋友们关注!其他药物类型如反义寡核苷酸(ASO)、细胞疗法(cell therapy)、小干扰RNA(siRNA)、未明确类型(N/A)各占2.6%,这些数据表明,尽管这些药物类型目前的交易数量较少,但它们代表了医药研发的前沿方向,具有巨大的发展潜力和市场前景。总体来看,2025年的交易数据揭示了医药行业在传统小分子药物领域的稳固地位,同时也展现了生物药和新型疗法的增长趋势。05靶点分布2025年跨国药企交易的靶点分布显示了显著的多样性。其中,38笔交易中有6笔没有披露靶点,占据了15.8%的比例,这可能指向了一些交易未具体披露靶点或涉及多靶点的情形。STAT6靶点以5.3%的比例位居第二,这反映了它在信号传导和细胞增殖中的重要性,尤其是在肿瘤治疗领域。多个靶点如5-HT2R、D2R、a4β7、TL1A、ACSL5等各占2.6%,这表明交易的靶点分布较为分散,药企对多种疾病领域的治疗靶点均表现出兴趣。此外,靶点如CD19、CD20等与肿瘤治疗相关,显示了肿瘤治疗依然是研发的重点。而像GLP-1R/GCGR/GIPR这样的靶点则指向代谢性疾病领域,当下减重新药红红火火,相关靶点备受关注,相信更多的交易在路上。整体来看,靶点的多样性反映了药企在寻求创新治疗方案时的广泛探索,同时也显示了对特定疾病领域如肿瘤和代谢性疾病的持续关注。06中国企业表现亮眼在2025年跨国药企的交易中,中国药企以及欧美药企在中国的业务表现突出,共完成了9笔交易,总金额达到68.88亿美元,占总交易金额的11.6%。这些交易不仅体现了中国药企在全球医药行业中日益增长的贡献和影响力,也反映了国际药企对中国市场的重视和信心。这些交易涉及了多种药物类型,包括小分子药物、肽类药物、抗体药物等,显示了中国药企在多个治疗领域的布局和发展潜力。此外,中国药企参与的交易涉及了多个治疗领域,如肿瘤、代谢性疾病、免疫与炎症等,为全球患者提供了更多的治疗选择。综上所述,中国药企在2025年的跨国药企交易中扮演了重要角色,为全球医药行业的发展做出了贡献。随着中国药企研发实力的不断提升和国际化步伐的加快,预计未来中国药企在全球医药交易中的地位和影响力将进一步增强,有朝一日,也可能像MNC一样,作为买方全球采购优质产品、公司,快速壮大规模和实力。参考资料:BigPharma M&A and Licensing Deals,YTD Apr'25关税阴云下,大型药企并购热情不减,哪些中国药企可能被收购?2024年制药行业并购TOP1028.4亿美元!4月中国创新药出海汇总其它公开资料图片来源:微信订阅号AI【直击现场】「星起点」宣讲会直播:50万资金+专家辅导,寻找下一个代谢病创新药突破者!2025-04-30百济神州索托克拉冲刺上市,引领BCL2抑制剂新纪元!2025-04-30双引擎强效驱动,药明康德一季度交出亮眼成绩2025-04-29精鼎医药学术论坛:运筹帷幄,把握全球药物研发趋势2025-04-29版权声明/免责声明本文为原创文章。本文仅作信息交流之目的,不提供任何商用、医用、投资用建议。文中图片、视频、字体、音乐等素材或为药时代购买的授权正版作品,或来自微信公共图片库,或取自公司官网/网络,部分素材根据CC0协议使用,版权归拥有者,药时代尽力注明来源。如有任何问题,请与我们联系。衷心感谢!药时代官方网站:www.drugtimes.cn联系方式:电话:13651980212微信:27674131邮箱:contact@drugtimes.cn点击这里,查看更多精彩!

并购抗体药物偶联物引进/卖出

2025-05-02

·医药魔方

5月1日,礼来发布2025Q1财报,总营收127.29 亿美元,同比增长45%。中国区收入4.51亿美元,同比增长20%。研发投入27.3亿美元,同比增长8%,占总收入的21.5%。礼来定义其核心产品为Ebglyss、Jaypirca、Kisunla、Mounjaro、Omvoh、Verzenio和Zepbound,上述几款产品Q1收入达75.2亿美元(+119%),主要由Mounjaro和Zepbound销售增长驱动。Mounjaro全球收入为38.4亿美元(+113%),其中美国市场营收为26.6亿美元(+75%),总处方量(TRx)占比39%,新处方量(NBRx)中占比46%;Zepbound在美销售额23.1亿美元,目前总处方量占比超过60%,新处方量占比74%。总体上,截至2025年Q1,礼来在美国肠促胰岛素类似物市场中占领先地位,总处方量占比增至53.3%,超过竞争对手诺和诺德。目前,礼来已通过LillyDirect在线医疗平台独家推出7.5mg和10.0mg规格的Zepbound单剂量药瓶,预计将进一步打开市场。此外,用于治疗乳腺癌的CDK4/6抑制剂Verzenio收入12.6亿美元(+18%),在美总处方量占比达43%。Jaypirca创收9200万美元,并在欧盟获得用于治疗经BTK抑制剂治疗后复发或难治性CLL的监管批准。Ebglyss收入6000万美元,Kisunla收入2100万美元;IL-23p19单抗mirikizumab(Omvoh)获FDA批准用于治疗成人中度至重度活动性克罗恩病。临床研究方面,礼来取得了多项进展:口服小分子GLP-1R激动剂Orforglipron的III期ACHIEVE-1研究取得积极结果,与安慰剂相比,Orforglipron在40周时达到了A1C降低更优的主要终点,从8.0%的基线平均降低A1C 1.3%至1.6%,且总体安全性与已确定的GLP-1类药物一致;siRNA疗法Lepodisiran II期临床ALPACA研究取得积极结果,Lepodisiran以最高测试剂量(400mg)治疗成人Lp(a)水平升高的患者后,Lp(a)水平较基线降低了近94%,达到主要终点;巴瑞替尼(Baricitinib)治疗青少年斑秃III期BRAVE-AA-PEDS研究取得积极数据。监管方面,Jaypirca(pirtobrutinib)获得了欧洲药品管理局(EMA)人用药品委员会(CHMP)的推荐批准,用于治疗复发或难治性慢性淋巴细胞白血病(CLL);CHMP不推荐批准donanemab用于治疗早期阿尔茨海默病,礼来将寻求复核。此外,礼来已完成对Scorpion Therapeutics公司小分子PI3Kα抑制剂STX-478的收购,该管线目前正在乳腺癌症和其他晚期实体瘤的I/II期临床试验中进行评估。 礼来预计,2025年将有多项III期临床试验和监管进展,全年收入指引将在580亿~610亿美元之间。Copyright © 2025 PHARMCUBE. All Rights Reserved.欢迎转发分享及合理引用,引用时请在显要位置标明文章来源;如需转载,请给微信公众号后台留言或发送消息,并注明公众号名称及ID。免责申明:本微信文章中的信息仅供一般参考之用,不可直接作为决策内容,医药魔方不对任何主体因使用本文内容而导致的任何损失承担责任。

财报临床3期临床2期siRNA

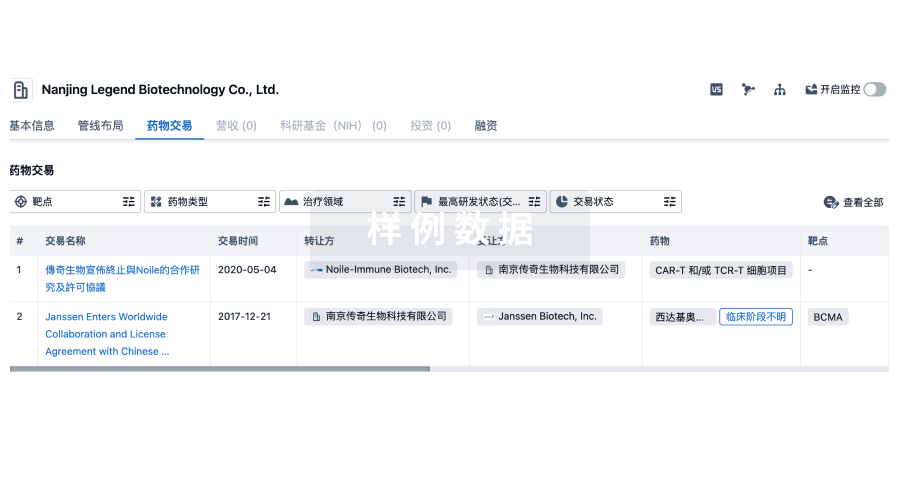

100 项与 Scorpion Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

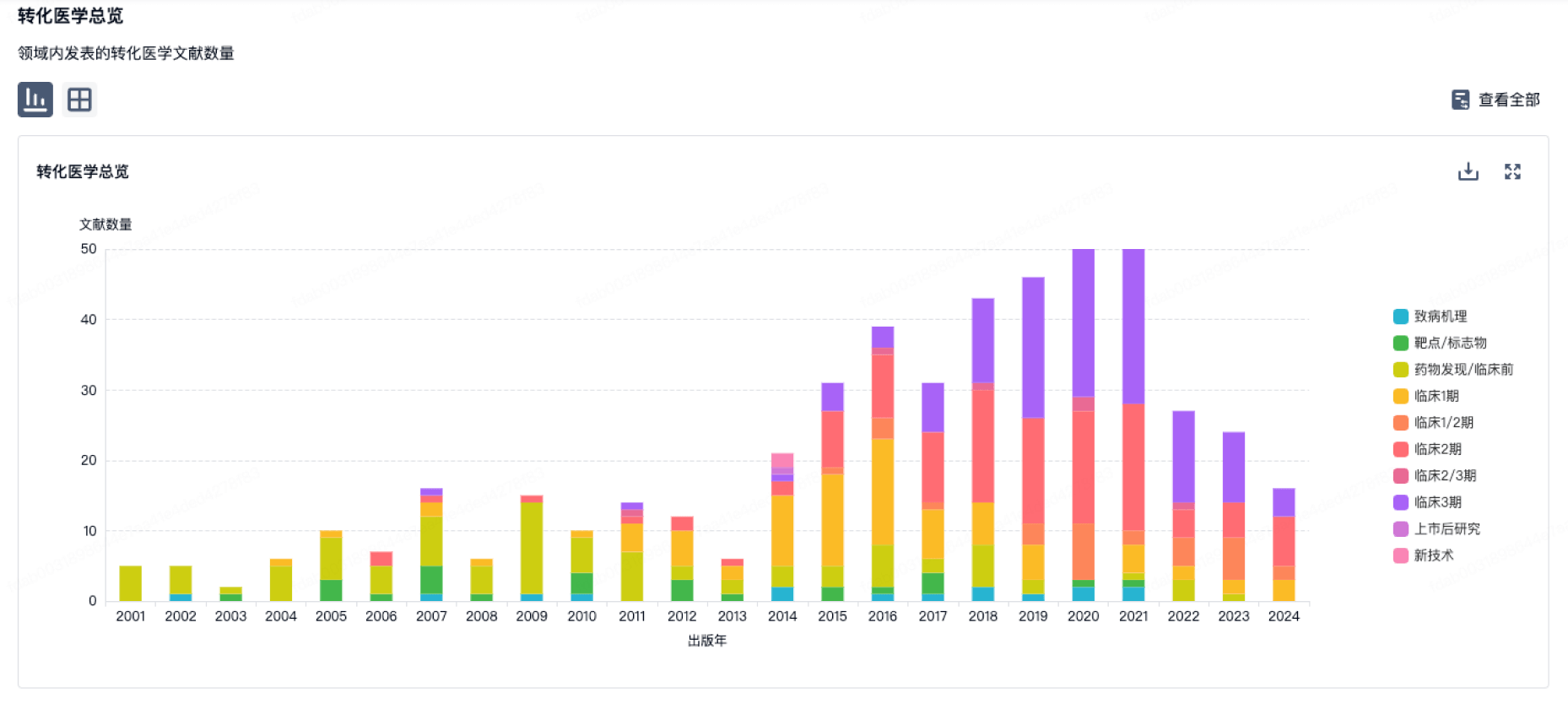

100 项与 Scorpion Therapeutics, Inc. 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

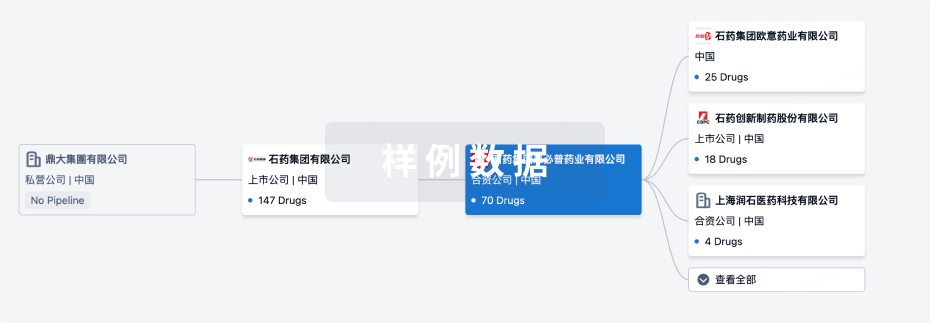

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2025年07月22日管线快照

管线布局中药物为当前组织机构及其子机构作为药物机构进行统计,早期临床1期并入临床1期,临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

临床前

1

2

临床2期

登录后查看更多信息

当前项目

登录后查看更多信息

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

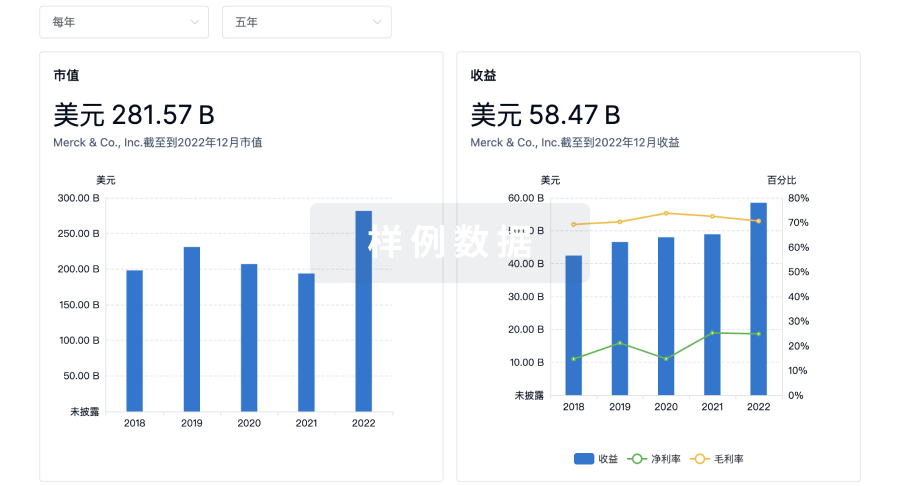

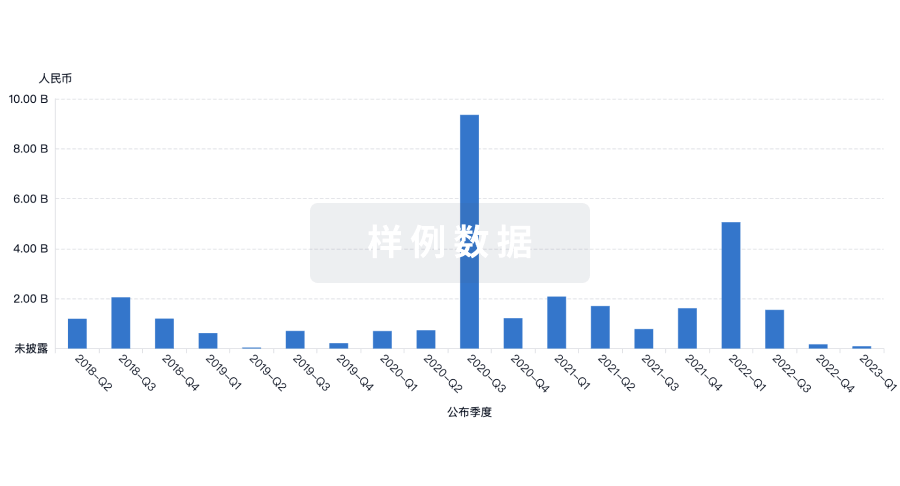

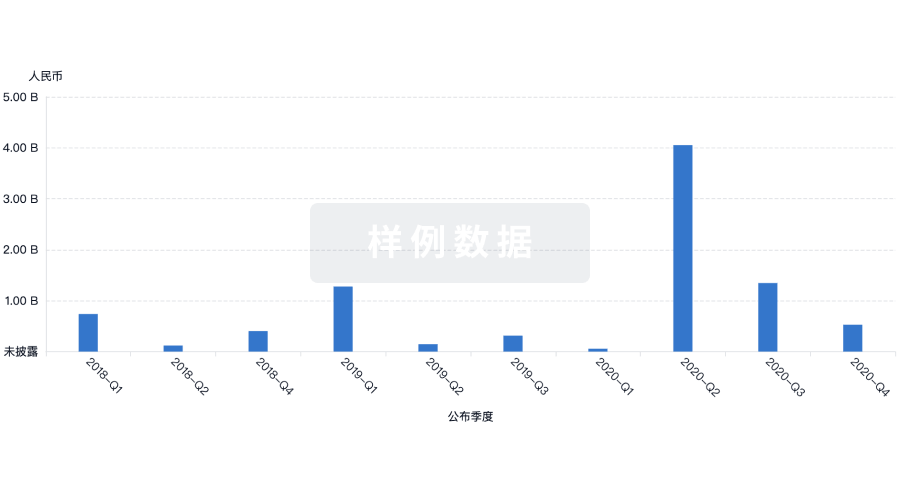

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

Eureka LS:

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用