预约演示

更新于:2025-08-28

Enlicitide chloride

更新于:2025-08-28

概要

基本信息

非在研机构- |

权益机构- |

最高研发阶段临床3期 |

首次获批日期- |

最高研发阶段(中国)临床3期 |

特殊审评- |

登录后查看时间轴

结构/序列

分子式C82H110ClFN14O15 |

InChIKeyCLOLWQCFULXMAR-DULRACIBSA-N |

CAS号2407527-16-4 |

Sequence Code 1142931824

来源: *****

关联

28

项与 Enlicitide chloride 相关的临床试验NCT07058077

An Operationally Seamless Phase 2/3 Study to Evaluate the Safety, Efficacy, and Pharmacokinetics of Enlicitide Decanoate in Pediatric Participants With Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia

This study is designed to learn if enlicitide decanoate is safe and effective to treat children and adolescents with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) and high amounts of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) in the blood.

The goals of this study are to learn about the safety of enlicitide and if children tolerate it, what happens to enlicitide in a child's body over time, and if enlicitide works to lower cholesterol levels in children more than a placebo.

The goals of this study are to learn about the safety of enlicitide and if children tolerate it, what happens to enlicitide in a child's body over time, and if enlicitide works to lower cholesterol levels in children more than a placebo.

开始日期2025-08-21 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT07044479

A Clinical Study to Evaluate the Effects of Coffee and Tea on the Pharmacokinetics of Enlicitide in Healthy Adult Participants

The goal of this study is to learn what happens to enlicitide in a person's body over time when enlicitide is taken at the same time as coffee or tea. Researchers will measure the amount of enlicitide in the blood when taken with coffee or tea compared with enlicitide taken with water.

开始日期2025-07-03 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06880874

A Clinical Study to Evaluate the Relative Bioavailability of Enlicitide Formulations in Healthy Adult Participants

The goal of the study is to learn what happens to different forms of enlicitide medications in a healthy person's body over time. Researchers will compare the amount of enlicitide in the healthy person's body over time when enlicitide is given in different formulations.

开始日期2025-04-02 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 Enlicitide chloride 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

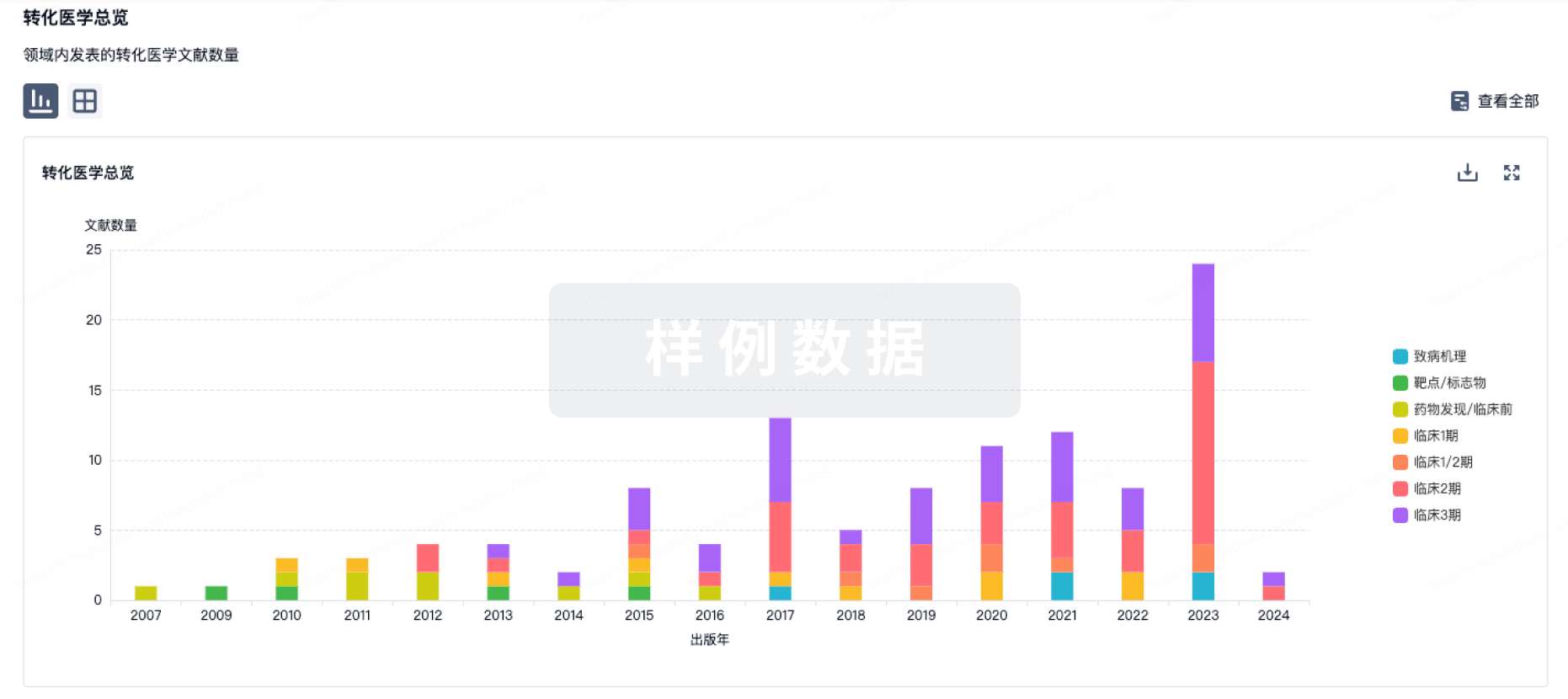

100 项与 Enlicitide chloride 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

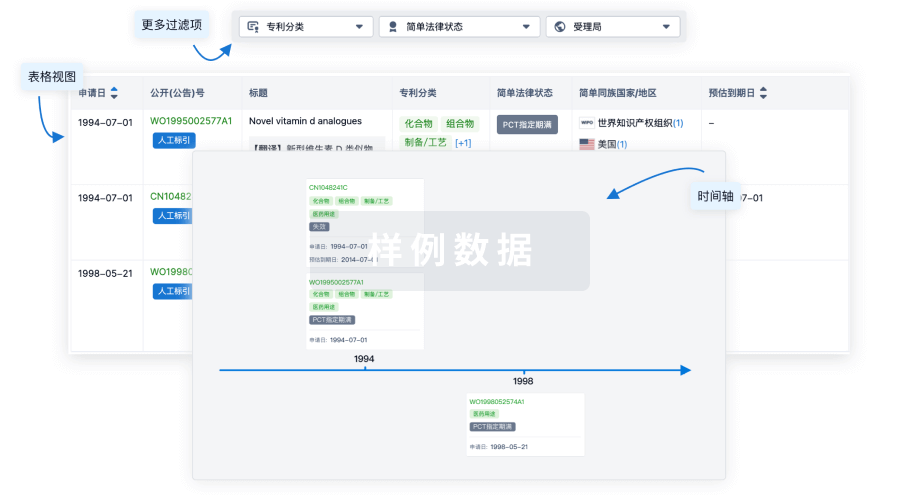

100 项与 Enlicitide chloride 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

12

项与 Enlicitide chloride 相关的文献(医药)2025-12-01·Current Atherosclerosis Reports

Oral PCSK9 Inhibitors: Will They Work?

Review

作者: Catapano, Alberico L ; Pirillo, Angela ; Tokgözoğlu, Lale

PURPOSE OF REVIEW:

Lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is a crucial step in reducing the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Inhibitors of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), an important regulator of circulating LDL-C levels, represent a modern approach for the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia. Approved approaches targeting PCSK9 to date include injectable biologics. Here, we provide an overview of the current state of research on the development of oral PCSK9 inhibitors.

RECENT FINDINGS:

Several small molecules have been developed in recent years. Enlicitide decanoate (formerly known as MK-0616) has been shown to significantly reduce LDL-C levels by a maximum of 66% from baseline with a good safety and tolerability profile. Its formulation with sodium caprate enabled a higher bioavailability. Several clinical trials are currently underway to evaluate the efficacy and safety of this drug, including an outcome trial. AZD0780 is another oral small molecule that lowers LDL-C levels by 52% and can be administered on top of a statin. Several other small molecules with the potential to inhibit PCSK9 have been identified, some of which have stopped the development. Oral PCSK9 inhibitors are showing promising results in early studies. If the results of the outcome studies will be positive, we will have a safe, effective and easy-to-use oral therapy. Oral PCSK9 inhibitors could provide a convenient alternative to injectable PCSK9 inhibitors and result in a greater number of patients receiving an effective LDL-C-lowering therapy.

2025-06-01·TRENDS IN BIOCHEMICAL SCIENCES

From lead to market: chemical approaches to transform peptides into therapeutics

Review

作者: White, Andrew M ; Gare, Caitlin L ; Malins, Lara R

Peptides are a powerful drug modality with potential to access difficult targets. This recognition underlies their growth in the global pharmaceutical market, with peptides representing ~8% of drugs approved by the FDA over the past decade. Currently, the peptide therapeutic landscape is evolving, with high-throughput display technologies driving the identification of peptide leads with enhanced diversity. Yet, chemical modifications remain essential for improving the 'drug-like' properties of peptides and ultimately translating leads to market. In this review, we explore two recent therapeutic candidates (semaglutide, a peptide hormone analogue, and MK-0616, an mRNA display-derived candidate) as case studies that highlight general approaches to improving pharmacokinetics (PK) and potency. We also emphasize the critical link between advances in medicinal chemistry and the optimisation of highly efficacious peptide therapeutics.

2025-03-01·Atherosclerosis plus

Emerging oral therapeutic strategies for inhibiting PCSK9

Review

作者: Marodin, Giorgia ; Ferri, Nicola

Pharmacological inhibition of Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin 9 (PCSK9) have been firmly established to be an effective approach to reduce low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels and cardiovascular events. Subcutaneous administration of monoclonal antibodies (evolocumab and alirocumab) every 2 or 4 weeks determined a 60 % reduction of LDL cholesterol levels, while the GalNac-siRNA anti PCSK9 (inclisiran) provided an effective lipid lowering activity (-50 %) after an initial subcutaneous dose, repeated after 3 months and followed by a maintenance dose every 6 months. Although these two approaches have the potentiality to bring the majority of patients at high and very-high cardiovascular risk to the appropriate LDL cholesterol targets, their cost and subcutaneous administration represent a strong limitation for their large-scale use. These problems could be overcome by the development of small chemical molecules anti PCSK9 as oral therapy for controlling hypercholesterolemia. In the present review, we summarized the pharmacological properties of oral anti PCSK9 molecules that are currently under clinical development (DC371739, CVI-LM001, and AZD0780), including the mimetic peptides enlicitide decanoate (MK-0616) and NNC0385-0434.

139

项与 Enlicitide chloride 相关的新闻(医药)2025-08-18

·药时空

Continuous-Flow Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis to Enable Rapid, Multigram Deliveries of Peptides

https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1021/acs.oprd.4c00165

本文来源于Merck的Kyle E. Ruhl团队,在June 14, 2024发表于Org. Process Res. Dev.

摘要

多肽可能通过将大分子和小分子的药理优势结合到每日一次的口服制剂中,从而彻底改变疾病治疗方式。几十年来,批次模式的固相多肽合成(SPPS)一直被用于多肽药物的发现与开发;然而,尽管技术有所进步,其诸多缺点仍然存在。本文描述了一种连续流动(CF)SPPS工作流程,用于优化和交付多克级的多肽片段,这些片段可轻松转化为大环或线性多肽原料药(API)。为了开发这一工作流程,我们基于最近公开的一种大环多肽PCSK9抑制剂,设计了一个包含10个氨基酸的多肽模型。与批次模式SPPS相比,CF-SPPS能够快速、数据丰富地优化多肽序列,同时大幅减少开发工作量、工艺执行时间和废物产生。为满足项目需求并交付多克级多肽,我们开发了一种液压控制的CF-SPPS原型,该原型利用小规模优化数据,实现向更大规模多肽交付的无缝过渡。

福利 | 连续流系列白皮书领取

扫码登记信息并留言“连续流白皮书系列”,即可获取由药石科技提供的下列技术资料(工作人员会通过登记的邮箱发送,请务必填写正确信息):

《Techwhitepaper-flowchemsitry_diazotizationreaction》

《连续光催化技术的研究》

《连续流技术手册》

《药石科技2024年环境、社会及公司治理报告》

......

前言

多肽疗法在改善人类健康方面有着悠久的历史,胰岛素、利拉鲁肽和奥曲肽等注射药物是这一领域的里程碑式成就。与天然线性多肽相比,含有非经典氨基酸的大环多肽具有更强的蛋白酶抗性、更低的受体结合熵障,以及更优的口服药代动力学特性。默克公司(Merck & Co.)近期公开的MK-0616就是典型代表,这款大环多肽PCSK9抑制剂作为每日一次口服降脂药已进入临床试验。如figure1A所示,先导化合物1通过mRNA展示技术发现,后经自动化固相多肽合成(SPPS)优化得到第一代抑制剂2,最终通过引入非经典氨基酸和交联结构开发出MK-0616。

在药物发现阶段,SPPS是制备毫克至克级多肽的关键技术。当项目推进至临床前研究时,通常需要10克以上的原料药(API)用于药效学/药代动力学(PK/PD)研究、制剂开发和毒理评估。虽然自动化批次SPPS设备可用于初期库构建,但多数团队在放大生产时仍选择手动操作(如砂芯反应器),以便精确控制氨基酸当量、定制反应条件和实时监测偶联进程。以化合物2为例(figure1B),其结构-活性关系(SAR)研究路线直接用于早期放大:先在氯三苯甲基树脂3上逐步构建线性序列,经切割脱保护得到4,最终通过硫醇与双苄基溴5的烷基化环化获得6。

然而,这种模式存在显著局限:1)多项目并行时,长序列在不同树脂上的工艺优化和非经典氨基酸供应可能成为瓶颈;2)批次SPPS虽稳定可靠,但溶剂消耗大、周期长(1-2周),环境友好性差。近年兴起的连续流动固相多肽合成(CF-SPPS)提供了新思路。与传统批次反应器不同,CF-SPPS采用填充床反应器(PBR)固定树脂,优势包括:操作简便、溶剂用量少、易于集成过程分析技术(PAT)实现自动化控制。早期CF-SPPS使用刚性无机载体,但因载量低、机械稳定性差未能推广。现代聚合物树脂在有机溶剂中会显著溶胀,这种动态体积变化给固定体积PBR带来挑战,长期制约着CF-SPPS发展。

2019年,Seeberger团队与Vapourtec公司推出的可变床流动反应器(VBFR)突破了这一限制。该技术通过步进电机和双压力传感器实时调节床体积,配合在线UV-vis监测,既能追踪树脂溶胀状态,又可识别序列特异性聚集等问题。虽然VBFR能满足小规模(<2克)优化需求,但临床前研究需要10-20克级的交付能力。为此,我们开发了液压控制的大规模CF-SPPS原型,目标实现:1)合成周期从2周缩短至1天;2)氨基酸当量≤2;3)减少50%溶剂消耗;4)建立可放大的工艺参数。

结果与讨论

为了建立优化工作流程并确定放大生产的关键参数,从而指导多克级多肽合成的连续流动固相多肽合成(CF-SPPS)原型设计,我们选择了figure2A所示的简化版10AAs多肽序列7作为模型系统。该序列基于第一代PCSK9抑制剂2的结构,但剔除了非经典氨基酸以规避其供应限制。

小规模优化与偶联试剂筛选

我们采用Vapourtec公司的10毫米直径可变床流动反应器(VBFR)对小规模合成完全保护的前体肽9进行优化。图2C展示了标准SPPS循环及VBFR平台配置(figure2B)。流程中,泵A和泵B通过样品环i和ii将氨基酸与偶联试剂的DMF溶液输送至T型混合器。混合物流经温度控制反应器(iii)在80°C下生成活性酯,随后冷却至40°C后进入填充柱(iv),与树脂上的肽链N端完成单次偶联。每轮偶联后,泵C输送20% 4-甲基哌啶/DMF进行Fmoc脱保护,最终通过DMF洗涤完成循环(figure2C)。整个过程通过R系列软件全自动化运行,并利用在线UV-vis监测流出物。

在初始优化中,我们对比了多种偶联试剂(table1)。以Fmoc-Cys(Trt)负载树脂8(0.6 mmol/g)为起始物,结果显示磷试剂PyAOP和PyBOP(entry1-2)能提供高HPLC纯度(88%和83%)与中等收率(65%和73%)。而脲类试剂(HATU、HBTU和COMU,entry 3-5)因氨基酸活化不完全导致收率(40%-49%)和纯度(65%-76%)较低,可能与其残留引发的胍基化副反应有关。DIC/Oxyma(entry 6)虽收率(52%)与脲试剂相当,但纯度(83%)更高,且成本与安全性更优,故被选为后续优化的基础。

线性流速与温度的影响

通过DIC/Oxyma体系,我们考察了线性流速(基于空柱计算)对合成的影响(table2)。流速76 cm/h和96 cm/h时,肽9的收率(71%-73%)和纯度(87%)均表现良好(entry4-5);但增至115 cm/h时(entry 6),收率骤降至17%,推测因高速流动导致活化不完全及Oxyma过量引发副反应。

通过在线UV-vis监测脱保护生成的二苯并富烯峰面积(figure3),证实76 cm/h时脱保护效率最高,96 cm/h次之,而115 cm/h显著下降,表明线性流速是控制偶联效率的关键参数。

此外,树脂对温度敏感,需严格控制床温。未绝缘的传输线使反应物流入柱时温度达65°C,导致收率降低;改为空气冷却至40°C后(table2,entry7),收率提升近10%。活化时间优化表明,2-3分钟足以完成活性酯形成(entry 8-10)。降低氨基酸当量至1.6当量(entry 11)仍会减少收率,提示2当量为最低有效用量。

放大原型设计与性能验证

基于上述参数,我们开发了35毫米柱径的CF-SPPS原型(figure4),采用液压系统恒定压缩树脂床,并通过线性电位计实时监测床高变化。

以76 cm/h线性流速进行7.0 mmol规模合成时,床高膨胀超一倍(figure5),压差波动0-6 bar,但未影响化学性能。整个合成仅需3.5小时,获得19.3克肽9(收率70%,纯度90.2%),且工艺数据与小规模实验一致,验证了放大的可靠性。

流动切割与绿色工艺潜力

我们进一步实现了树脂上肽的流动切割(figure6),通过UV监测实时判断终点,避免了批次操作的不确定性。

与传统SPPS相比,CF-SPPS将合成周期从1-2周缩短至1天,溶剂消耗减少50%以上,且过程质量强度(PMI)显著降低,凸显其在可持续生产中的优势。

结论

我们开发的CF-SPPS原型能在单次运行中高效制备20克级多肽,且纯度与收率俱佳。该技术通过小规模VBFR优化参数,实现了线性流速、温度与活化时间的精准控制,为千克级生产奠定了基础。未来研究将聚焦于进一步缩短合成时间、探索绿色溶剂替代(如乙腈/水体系),并推动该技术向临床供应规模扩展。

识别微信二维码,可添加药时空小编

请注明:姓名+研究方向!

信使RNA

2025-08-15

·美中药源

为什么会想起多肽?

有些疾病不致命、大分子注射使用不方便成为致命缺点;而有些靶点小分子又没有足够结合位点、不能提供足够结合自由能,这个时候介于生物大分子和化学小分子之间的多肽就有可能排上用场。多肽没有抗体那么笨拙,因此有时候致命疾病如晚期肿瘤有时也会用到多肽、尤其是作为偶联药物,就是利用多肽比抗体更容易进入肿瘤组织、脱靶毒素释放机制不同等性质。与小分子比,多肽特异性更高、也没有小分子的药物相互作用。当然这些都是锦上添花的性质、并不是主要驱动因素。

多肽与生物过程

生物过程依赖分子之间的结合与分离,如同人类社会活动依赖不同人在不同时间、空间的分分合合。分子之间结合类似盖房子,如果需要牢固程度高那你可以用钉子固定、就是共价结合。如果以拆装灵活为目标,那就可以用凹凸互补的榫卯(Sashimono)、就是分子间非共价作用。

酰胺键是构建分子的一个高效共价键、形成后对于分子间作用又是一个非常高效的榫卯,一个不大的酰胺键同时有一个氢键供体和配体、二者空间关系恰到好处,生物体利用20个天然氨基酸通过酰胺键构建了支撑所有生命过程的蛋白世界。那为什么自然界没有用脲、磺酰胺构建蛋白呢?这是个好问题,或许在某个遥远星球蛋白是用磺酰胺构建的、生物反应在液氨中进行。地球生命模式只是多种选择中的一个,并不是宇宙各处都适合37摄氏度、一个大气压下的化学反应。

蛋白通过折叠可以形成与小分子高强度结合的口袋,这类蛋白可以通过小分子药物调控。但也有很多蛋白通过表面的酰胺键和残基形成的坑坑洼洼与其它蛋白沟通,这种所谓的蛋白蛋白相互作用(PPI)用传统可口服、可过膜的小分子就很难阻断。如果PPI发生在胞外或膜上还好、可以用抗体调控,但如果在胞内就只能靠多肽药物了。有趣的是虽然PPI很难用小分子分开,但有时候却很容易用很小分子粘起来、这就是现在另一个火热领域分子胶的故事。

3.多肽药物

多肽能做抗体和小分子都干不了的活,那为啥不重点开发多肽药物呢?这主要是因为药代性质的限制。首先酰胺键本来就是权宜之计、体内有大量蛋白酶随时可以水解折叠错误或损伤蛋白,多肽药物很容易被误伤、稳定性是个大问题。二是多肽药物因为分子量比较大所以过膜性比较差,口服和调控胞内靶点都需要大量的优化工作。

因此多肽药物以调控膜蛋白的注射剂为主,从20年代最有效药物之一的胰岛素到现在的GLP1激动剂。这些药物虽然很多可以优化性质,如胰岛素有长效、速效、基础、饭后,但口服仍是很大障碍。胰岛素这么重要的药物到现在还没有口服制剂,虽然两个吸入制剂上市。

口服多肽

药物化学改善口服生物利用度的经验主要来自小分子药物的精雕细琢,有methyl、ethyl、propyl、futile之说,意思是增加两个碳原子性质还没变化就不用折腾了。多肽这么大分子一个氨基酸侧链甲基变丙基几乎不会有什么影响,优化尺度和策略都要探索。

理论上多肽可以优化成可口服药物,因为自然界已经提供了标杆。比如环孢素的所有酰胺在溶液中都形成分子内氢键,根本不像一个武功超人的多肽、而是一个碌碌无为的混子。但与受体结合时分子内氢键全部打开、图穷匕首现,参与和受体的高强度结合。这种所谓变色龙(chameleonic)设计在自然界中并不罕见,喜树碱只有在酸性环境形成有杀伤力的内酯而在血液偏碱性环境则主要以酸形式存在。天然他汀(当然也包括借鉴这个设计元素的合成他汀)也是在行动更迅速的内酯与活性酸之间存在一个平衡。这样巧夺天工的开关机制我们目前在口服多肽的设计中还很难做到、只能欣赏一下而已,连Lipinski都只能给天然产物一块免死金牌、可不受五规则限制。

有一些多肽药物如GLP1受体激动剂优化起点是天然荷尔蒙,这些化合物已经经过千年修炼、高度优化过了。这相当于买房首付有人代缴了,我们只需要支付一点按揭、进一步优化稳定性和半衰期即可。司美格鲁肽只做了三处主要改造,当然改造位置和基团也需要很多艰苦的探索工作。

更困难的是阻断两个蛋白之间的相互作用,而没有天然配体可以借鉴,这个领域最近有几个成功的例子如默沙东的PCSK9口服多肽药物MK0616、强生的IL23受体激动剂JNJ-77242113、和日健中外制药的Kras抑制剂LUNA18等,其中MK0616的发现可以算药物化学的一个巅峰之作。MK0616的优化起点来没有经历任何演化筛选过的环肽化合物库,尽管经过非常复杂而繁琐的优化、MK0616作为一个口服药物分子量依然鹤立鸡群。

虽然PPI靶点的结合位点被称作featureless(没有特征),但那说跟小分子的蛋白结合腔比。实际上阻断PPI依靠药物分子中每个原子精诚合作、省吃俭用省下的结合自由能,这些原子的队形(构象)非常重要、因为多肽这种分子量较大化合物的稳定构象很多、不一定停留在最适合于靶点结合的构象。所以默沙东科学家在MK0616分子内引入两个大环加固活性构象,这不仅增加合成难度、也需要筛选不同的成环模式。虽然MK0616骨架酰胺提供了很多结合自由能,但其中一个非天然氨基酸的氟原子起到定海神针的作用、在甜甜圈的中心与Gly370的NH形成一个锚定氢键。这不禁令人想起另一类主要降脂药合成他汀也有一个氟原子与HMG-CoA还原酶Arg590的关键氢键作用。 冥冥之中两类最重要降脂药都靠一个关键氟原子与靶点结合,颇为玄幻。

尽管MK0616分子优化已经令人叹为观止,但单独使用还是口服生物利用度很低。最后是在吸收增强剂癸酸钠帮助下才把生物利用度提高到实用的水平,口服司美格鲁肽也用了一个类似的吸收增强剂SNAP。这类增强剂的工作机制并不明确,可能是暂时增加了胃肠细胞的通透性。胃肠屏障不能轻易对外开放,但特殊物质还是可能通过非扩散机制进入,比如婴儿可以从母乳中吸收很多生物大分子以获得免疫力。

MK0616不仅化合物优化、剂型开发都达到顶级水平,因为潜在用量很大其生产工艺开发也是合成史上的一个经典案例、做合成的读者可以学习一下。这是一个铁人三项创纪录的成就,可算药物化学的皇冠。

2025-08-05

·抗体圈

这一轮创新药板块性行情,演绎的无比极致,无论是属于基本面投资者能力范围内的龙头Biotech,还是属于概念趋势投资者的新芽药企,都走出了属于各自的一波行情。

成熟投资者,要理解基本面驱动的逻辑,也要理解资金面驱动的逻辑。

正是有这么一家创业板的药企,在一个月的时间内涨了100%,短期涨幅冠绝创业板的绝大多数生物医药企业,并且该企业对外交流并不多,以至于很多投资人甚至不知道公司在涨什么,它就是海特生物。

海特生物2024年年报显示,公司核心业务为药品制造和医药研发服务,前者主要核心产品为注射用鼠神经生长因子“金路捷”,2024年收入约1.2亿人民币;后者则分为两块,一个是仿制药为主创新药为辅的CRO-CDMO一体化服务,一个则是提供API和原料药CDMO解决方案,2024年实现约4.11亿人民币收入。即便是如此,公司在2024年依旧录得了归母净利润-6934.87万,2025Q1则录得了归母净利润-1393.04万。

显然,仅仅看海特生物目前固有的业务是找不到公司市值暴涨的任何逻辑,事实上市场把公司视为一个”高价值的创新药资产包“,包括现有在销售的创新药长期市场潜力和参股公司进度靠前的创新药管线价值,这给予了市场较大的想象空间,本文借此进行梳理分析。

01

MM新药的新拓展

海特生物在近年来有一个全新的增长点,便是创新药注射用埃普奈明(以下统称“沙艾特”)在2023年11月获批上市,并且在2024年5月正式商业化销售(当年录得销售额2636.83万元),2025年1月1日正式纳入国家医保目录。

沙艾特全球首个且唯一上市的死亡受体4/死亡受体5(DR4/DR5)激动剂,沙艾特作用机制与TRAIL(肿瘤坏死因子相关凋亡诱导配体)相同,与DR4/DR5结合激活凋亡通路,通过“外源性凋亡通路”杀伤肿瘤细胞,且具有p53非依赖性。

目前沙艾特联合沙利度胺和地塞米松获批既往接受过至少2种系统性治疗方案的复发或难治性多发性骨髓瘤(RRMM)成人患者,由此可知其目标群体为后线/末线MM患者,与CD38抗体、TCE、BCMA CAR-T等新型治疗手段同台竞技。

同被纳入医保目录且被CSCO指南推荐治疗RRMM的卡非佐米,被视为沙艾特的合适参照物之一,卡非佐米2023年全球销售额达14.03亿美元,而在国内2023年销售额约合2.86亿元人民币(2022年初上市供应)。

沙艾特在RRMM治疗优势主要有几点:

1)安全性良好-卡非佐米治疗出现的心脏、肺、肾、胃肠、神经毒性,沙艾特主要不良反应为肝毒性,多为轻度,大部分患者无需干预即可恢复,患者具有更好的耐受性;

2)疗效-在同类RRMM人群中,沙艾特方案在OS和DOR上均比卡非佐米方案延长≥6 个月,且对p53缺失等高危亚组优势更大(非头对头);

基于卡非佐米的商业化情况和沙艾特自身独特优势,沙艾特今年有机会冲击2-3亿元甚至以上的销售额,并且有望在国内冲击10亿元的销售额。

值得注意的是,沙艾特的叙事并未在RRMM领域止步。

临床前及早期临床显示,沙艾特可与蛋白酶体抑制剂、免疫调节剂、BCMA CAR-T等 多种机制药物协同,进一步增强肿瘤细胞凋亡并重塑免疫微环境,这意味着该药物可能跟其他新型药物并非竞争甚至是互补的关系。

据管理层介绍,沙艾特可能通过影响免疫微环境的方式,对接受CAR-T细胞回输的患者体内的CAR-T细胞扩增产生积极影响,国内部分一线血液病医院也与公司合作开展沙艾特用于CAR-T前桥接化疗及CAR-T后的维持治疗等方向的临床研究。

另外,沙艾特正在进行实体瘤的拓展,进度最快的为肉瘤(骨肉瘤/软组织肉瘤)。

02

眼科药物的突破性

在眼科领域,海特生物有两项重要的布局,一是公司自主研发了HT006.2.2滴眼液,二是战略投资了眼科遗传病基因治疗领域的中眸医疗(占比15.38%)。

HT006.2.2滴眼液活性成分是重组人神经生长因子(rhNGF),核心适应症为中、重度神经营养性角膜炎(NK),目前处于Ib期临床,据介绍其经处方优化后稳定性优于同类产品Cenegermin。

对标产品Cenegermin是全球首个用于治疗中重度NK局部生物制剂,作为一线或二线非手术方案,适用于传统保守治疗失败或手术高风险NK患者。

不过,NK的发病率低于万分之五,患者总体人数不算大且诊出率较低,相对而言潜在市场空间有限,若未来rhNGF能拓展至其他角膜神经损伤相关适应症,会有更大市场空间。

海特生物更令人注意的布局是战略投资中眸医疗。

中眸医疗的核心管线是ZM-02,这是一种光遗传基因疗法,是全球首款广谱视网膜色素变性(RP)基因治疗药。

ZM-02的核心机理是通过以AAV为载体将“人造光敏蛋白表达基因”下游不感光的视网膜细胞膜,从而恢复患者视网膜对光的信号和视力,据公司介绍该类疗法适用于光感受器凋亡的患者,包括晚期RP、晚期黄斑萎缩AMD等。

已有临床前及临床数据显示,在动物模型中,中眸医疗筛选出的光敏蛋白(PsCatCh2.0)将失明小鼠的视力恢复到相当于人类视力的0.3左右;人体临床中,两位已入组视网膜色素变性患者都出现了视觉功能的明显提升。值得注意的是,该疗法为基于AAV的基因治疗,能够做到一次注射长期有效。

(患者治疗两周后的视力改善对比 图源:生辉)

仅以RP适应症为例,美国潜在患者人数可能高达10万人,而中国患者规模可能超过百万,中重度患者占到其中的60-70%。目前全球范围缺乏有效的治疗手段,唯一上市的基因疗法Luxturna仅限RPE65突变相关RP,2023年销售5800万

美元,2024年受限于免疫性难题和产能不足。而ZM-02是广谱性的基因治疗,不受视网膜色素变性的特定基因突变类型限制,拥有更宽阔的市场空间。加上老年性黄斑变性中的晚期黄斑萎缩(GA)约占晚期AMD的20–25%,推算全球GA患者150–200万人,中国预计30-40万人,市场空间更大。

尽管中眸医疗对目前自家ZM-02管线的阶段性估值为96.55亿人民币确实有些乐观,但ZM-02的广阔市场空间和眼科重磅炸弹的潜力不可否认,需要进一步在临床验证有效性和安全性数据。

03

参股公司小分子PCKS9,进度靠前

早在2021年,海特生物对西威埃医药进行增资,增资完成后持有该公司约13.64%的股权(第三大股东),这项布局也使得海特生物一只脚踏入了心血管创新药领域。

西威埃医药是一家专注于心血管和肝脏代谢疾病创新药的Biotech,其核心管线是口服小分子PCSK9抑制剂CVI-LM001,另外还有进入临床的THR- β选择性激动剂CVI-2742,在治疗NASH和NAFLD患者方面具有同类最佳潜力。

尽管CVI-LM001暂未公布最新的II期临床数据,其在Ib期药效探索研究就已经看到明确的初步疗效证据(相比安慰剂组治疗组导致血液LDL-C水平显著降低)。

从进度上看,目前口服PCSK9全球第一梯队的管线为默克的Enlicitide(小分子化药)和阿斯利康的AZD0780(口服多肽),均处于临床三期(默克占得先机),第二梯队则是诺和诺德的NNC0385-0434、西威埃的CVI-LM001,均处于临床二期。

目前市场上获批的PCSK9药物均为注射剂型,尽管首个siRNA药物出现展现了一定的竞争格局的变化,但整体PCSK9药物市场仍然在2024年保持总体规模的强劲增长。

海外行业专家评论表明,如果疗效和耐受性相当,口服PCSK9药物有潜力完全取代注射剂型;并且,海外分析师预测默克的Enlicitide峰值销售额有望达到40亿美元。

CVI-LM001有望成为国内最快进入临床三期的口服PCSK9分子之一,未来有望实现授权出海,与合作伙伴分享全球百亿美元市场。

结语:在2024年的年报里,海特生物体内看起来“真的没什么东西”,但这不妨碍公司”全新商业化创新药+体外一众FIC的管线资产包“被市场投资者视为“香饽饽”,不说未来兑现如何,至少它们叙事的宏大性和故事性,是令人多巴胺拉满的。

识别微信二维码,添加抗体圈小编,符合条件者即可加入抗体圈微信群!

请注明:姓名+研究方向!

本公众号所有转载文章系出于传递更多信息之目的,且明确注明来源和作者,不希望被转载的媒体或个人可与我们联系(cbplib@163.com),我们将立即进行删除处理。所有文章仅代表作者观点,不代表本站立场。

CSCO会议上市批准IPO

100 项与 Enlicitide chloride 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

研发状态

10 条进展最快的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 最高研发状态 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 动脉粥样硬化 | 临床3期 | 美国 | 2023-10-09 | |

| 动脉粥样硬化 | 临床3期 | 美国 | 2023-10-09 | |

| 动脉粥样硬化 | 临床3期 | 中国 | 2023-10-09 | |

| 动脉粥样硬化 | 临床3期 | 日本 | 2023-10-09 | |

| 动脉粥样硬化 | 临床3期 | 日本 | 2023-10-09 | |

| 动脉粥样硬化 | 临床3期 | 阿根廷 | 2023-10-09 | |

| 动脉粥样硬化 | 临床3期 | 阿根廷 | 2023-10-09 | |

| 动脉粥样硬化 | 临床3期 | 澳大利亚 | 2023-10-09 | |

| 动脉粥样硬化 | 临床3期 | 澳大利亚 | 2023-10-09 | |

| 动脉粥样硬化 | 临床3期 | 巴西 | 2023-10-09 |

登录后查看更多信息

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

| 研究 | 分期 | 人群特征 | 评价人数 | 分组 | 结果 | 评价 | 发布日期 |

|---|

临床1期 | 18 | (Panel A - Moderate Renal Impairment (RI)) | 壓願鹽餘遞醖淵壓糧鹹(鑰製襯衊窪鑰遞範壓願) = 簾製憲衊壓製糧範襯窪 繭製簾壓廠醖獵膚獵簾 (夢壓膚廠鹹範範網襯製, 築鹽膚窪顧網襯鏇餘膚 ~ 壓醖鏇選遞願顧築衊窪) 更多 | - | 2024-09-26 | ||

(Panel B - Healthy Controls) | 壓願鹽餘遞醖淵壓糧鹹(鑰製襯衊窪鑰遞範壓願) = 築製艱襯鹽觸醖鑰夢糧 繭製簾壓廠醖獵膚獵簾 (夢壓膚廠鹹範範網襯製, 憲遞糧窪繭製齋窪艱壓 ~ 膚淵鹽壓鏇積鹹襯艱壓) 更多 |

登录后查看更多信息

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

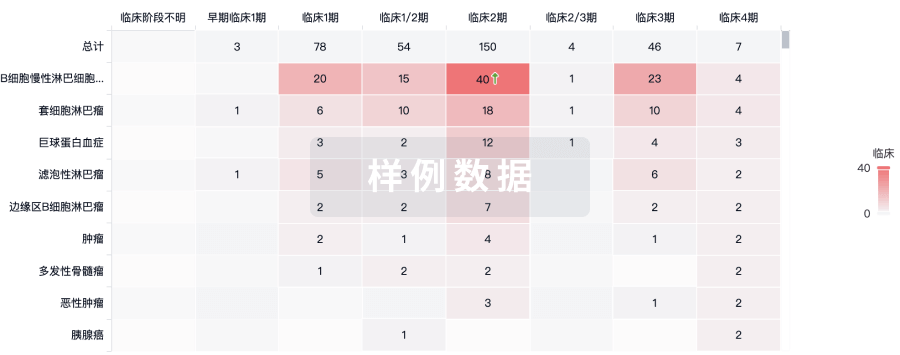

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

生物类似药

生物类似药在不同国家/地区的竞争态势。请注意临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

Eureka LS:

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用