预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

Neck, shoulder and arm syndrome

颈、肩、臂综合征

更新于:2025-05-07

基本信息

别名 Neck, shoulder and arm syndrome、頚肩腕症候群、颈肩综合征 + [1] |

简介- |

关联

3

项与 颈、肩、臂综合征 相关的药物作用机制 5-HT receptor调节剂 [+1] |

在研机构 |

原研机构 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 中国 |

首次获批日期2003-12-09 |

靶点 |

作用机制 COX抑制剂 |

在研机构 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 日本 |

首次获批日期1986-03-01 |

53

项与 颈、肩、臂综合征 相关的临床试验CTR20250266

盐酸乙哌立松片在空腹及餐后条件下的人体生物等效性试验

考察健康受试者在空腹及餐后条件下,单次口服1片由湖南华纳大药厂股份有限公司提供的盐酸乙哌立松片【受试制剂,规格:50mg】与相同条件下单次口服1片由卫材(中国)药业有限公司持证的盐酸乙哌立松片【参比制剂,商品名:妙纳®,规格:50mg】的药动学特征,评价两制剂间的生物等效性和安全性,为该受试制剂注册申请提供依据。

开始日期2025-03-27 |

申办/合作机构 |

CTR20244576

在中国健康受试者中随机、开放、两周期、双交叉餐后状态下洛索洛芬钠控释片与洛索洛芬钠片药代动力学比较试验

主要目的:以药代动力学参数作为主要终点评价指标,比较在餐后状态下口服受试制剂洛索洛芬钠控释片(规格:90mg,生产厂家:越洋医药开发(广州)有限公司)与对比制剂洛索洛芬钠片(规格:60mg,持证商:第一三共制药(上海)有限公司)后在中国健康受试者体内的药代动力学行为,评价两种制剂的生物等效性。次要目的:观察受试制剂洛索洛芬钠控释片和对比制剂洛索洛芬钠片在中国健康受试者中的安全性。

开始日期2024-12-27 |

申办/合作机构 |

CTR20244465

盐酸乙哌立松片餐后生物等效性试验

评价中国健康成年受试者餐后条件下单次单剂量口服盐酸乙哌立松片受试制剂(规格:50mg,申办者:山东京卫制药有限公司)和参比制剂(商品名:妙纳®,规格:50mg,持证商:卫材(中国)药业有限公司)后的药代动力学特点和生物等效性。

开始日期2024-12-26 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 颈、肩、臂综合征 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 颈、肩、臂综合征 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 颈、肩、臂综合征 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

143

项与 颈、肩、臂综合征 相关的文献(医药)2025-06-01·North American Spine Society Journal (NASSJ)

Opioid-use disorder and reported pain after spine surgery: Risk-group patterns in cognitive-appraisal processes in a longitudinal cohort study

Article

作者: Caan, Olivia B ; Finkelstein, Joel A ; Rapkin, Bruce D ; Schwartz, Carolyn E ; Borowiec, Katrina ; Skolasky, Richard L ; Sutherland, Tai

2025-02-25·Zhen ci yan jiu = Acupuncture research

Clinical observation on the efficacy of ringheaded thumb-tack needle therapy combined with tuina and active functional exercise in the treatment of neck-type cervical spondylosis.

Article

作者: Yang, Sheng-Ping ; Zhang, Zhi-Long ; Zhanghan, Yu-Jia ; Chen, Tian-Xin ; Zhu, Yu-Qi ; Xin, Tian-Xiang

2023-08-01·Clinical Spine Surgery: A Spine Publication

Does Cranial Fusion Level Affect Neck Symptoms?

Article

作者: Hasegawa, Kazuhiro ; Shibuya, Yohei ; Tashi, Hideki ; Makino, Tatsuo ; Watanabe, Kei ; Ohashi, Masayuki ; Hirano, Toru

7

项与 颈、肩、臂综合征 相关的新闻(医药)2025-04-25

·医脉通

今天的医疗圈发生了哪些与你有关的大事?更新、更全的医学动态3分钟一网打尽********今日关键词:2025年两院院士增选,医疗反腐,张文宏来源 | 医脉通作者 | 晚报君新闻60秒➤“医生举报3岁男童疑遭虐待”的视频热传,警方介入后回应@中国青年报 近日,一则医生接诊疑似被虐待儿童的视频在网络传播,引发广泛关注。一位自称浙江大学医学院附属儿童医院的叶医生发视频称,其接诊时遇到一名3岁男童,患儿全身多处受伤,经检查发现颅骨骨折、颅内血肿,并伴有多处撕裂伤。该医生怀疑孩子遭到长时间虐待,伤情可能为人为所致。该视频在多个平台发布,不少网友留言愤怒声讨。目前,原视频已不可见。据现代快报消息,4月23日上午,记者联系到浙大儿童医院。工作人员表示,医院确有该名叶姓医生,但并不了解其所述具体就诊情况,也不掌握相关患儿信息。工作人员强调,该事件并非医院官方发布,视频所述内容需进一步核实。另据大皖新闻报道,4月24日上午,杭州市公安局拱墅区分局武林派出所工作人员回应称,公安机关已经关注到网上视频情况并开展调查,网传小孩的情况是在异地发生,小孩是来杭州就诊,犯罪嫌疑人已经被当地公安机关采取强制措施,目前孩子处于安全状态。➤2025年两院院士增选,启动!@人民日报健康客户端 4月25日,中国工程院和中国科学院发布2025年院士增选指南。2025年中国工程院院士增选总名额为不超过100名,其中医药卫生学部12名(含中医药2名);中国科学院生命科学和医学学部拟增选19名院士。反腐60秒➤退休一年后,一医科大学副校长主动投案@“南粤清风”微信公众号、长安街知事 据广东省纪委监委4月25日消息,南方医科大学原党委常委、副校长宁习洲涉嫌严重违纪违法,主动投案,目前正接受纪律审查和监察调查。公开资料显示,宁习洲曾任南方医科大学党委组织部部长兼统战部部长,校长助理兼党委宣传部部长等职。2014年12月,宁习洲任南方医科大学党委常委、副校长,2024年1月退休。➤石河子大学第一附属医院原党委副书记、院长史晨辉主动投案@“清风兵团”微信公众号 石河子大学第一附属医院原党委副书记、院长史晨辉涉嫌严重违纪违法,主动投案,目前正接受新疆生产建设兵团纪委监委纪律审查和监察调查。医药60秒➤部分药品、医疗器械不再按进出境特殊物品监管@海关总署 4月24日,海关总署发布,经会签生态环境部、农业农村部、国家药监局同意,海关总署印发《海关总署关于明确部分货物、物品不再按进出境特殊物品监管的公告》,明确了海关对纳入药品、兽药、医疗器械管理的货物、物品,以及进出口环保用微生物菌剂不再按进出境特殊物品进行监管。➤张文宏团队公布广谱抗猴痘药物研发进展,将进入临床审批阶段@华山感染 4月24日,据华山感染,国家传染病医学中心主任、上海感染与免疫科技创新中心(广州国家实验室上海基地)主任张文宏教授日前在第三届感染病学术周上宣布,其团队在《信号转导与靶向治疗》杂志上发表了最新研究成果。首次获得比美国国立卫生研究院(NIH)用于临床研究的抗猴痘药物更强更广谱的新型抗病毒药物,为未来正痘病毒(如天花及其同类病毒)的潜在风险做了重要的技术储备。目前该药物即将进入临床审批阶段。➤千金药业富马酸比索洛尔片获批@千金药业 4月24日,千金药业公告,公司子公司获得国家药监局核准签发的富马酸比索洛尔片(2.5毫克、5毫克)《药品注册证书》。富马酸比索洛尔片是选择性β受体阻滞剂,用于治疗高血压、冠心病(心绞痛)、伴有心室收缩功能减退(射血分数≤35%)的慢性稳定性心力衰竭。➤华邦健康洛索洛芬钠口服溶液获批@华邦健康 4月24日,华邦健康公告,公司子公司获得国家药监局核准签发的洛索洛芬钠口服溶液《药品注册证书》。洛索洛芬钠口服溶液主要适用于类风湿关节炎、骨性关节炎、腰痛症、肩关节周围炎、颈肩腕综合征、牙痛;手术后、外伤后及拔牙后的镇痛和消炎等。责编|亦一封面图来源|医脉通医改新举措发布!一地缩减行政科室23个,降低行政后勤人员薪酬,绩效分配向临床一线倾斜三明医改2025年首站!“一把手”亲自抓医改,改革薪酬分配制度,提高医务人员固定收入占比医脉通是专业的在线医生平台,“感知世界医学脉搏,助力中国临床决策”是平台的使命。医脉通旗下拥有「临床指南」「用药参考」「医学文献王」「医知源」「e研通」「e脉播」等系列产品,全面满足医学工作者临床决策、获取新知及提升科研效率等方面的需求。☟戳这里,更有料!

高管变更疫苗

2024-11-21

文章来源:北京药研汇

非甾体抗炎药(NSAIDs)是不含类固醇甾体结构的一大类抗炎症药物,用于治疗风湿病、类风湿病、炎症、组织损伤、发热等病症。由于这类药物具有胃肠道副作用小、镇痛效果明显等优点,NSAIDs 的临床应用已有 100 多年,据不完全统计,全球每天约有 3000 万人在使用这类药物。

11月15日,中国国家药品审评中心(CDE)官网最新显示,合肥启旸生物医药科技有限公司按注册分类3类申报的洛索洛芬钠口服溶液上市申请获得受理。公开资料显示,洛索洛芬钠口服溶液其适应症为类风湿关节炎、骨性关节炎、腰痛症、肩关节周围炎、颈肩腕综合征、牙痛的消炎和镇痛;手术后,外伤后及拔牙后的镇痛和消炎;急性上呼吸道炎(包括伴有急性支气管炎的急性上呼吸道炎)的解热和镇痛。

洛索洛芬钠是第一个丙酸类前体型非甾体抗炎药(NSAIDs),属于前体药物,本身没有活性,口服后需经肝脏代谢,转化成trans-OH型药物以后才能发挥其治疗作用,其应用范围广,具有较好的镇痛、消炎、解热作用,尤其是镇痛作用较强。

据相关临床数据公开显示,洛索洛芬钠止痛效果是布洛芬、酮洛芬、萘普生的10-20倍,起效迅速且安全性比较高。洛索洛芬钠口服后最快15分钟起效,30分钟血浆浓度就达到峰值,一篇发表在Pharmacology上的文献表明,服用洛索洛芬4小时退热1.25度,而布洛芬则为0.76度。同时镇痛作用效果能达6-8小时。

洛索洛芬钠原研是日本第一三共制药,最早于1986年7月在日本获批上市,商品名为Loxonin,现为日本非甾体抗炎药中销量第一的品种。洛索洛芬钠口服溶液则最早于2001年由日医工株式会社在日本上市,截至目前口服液原研只在日本上市,国内无原研上市。

国内仿制药情况,洛索洛芬在国内已有贴膏剂、片剂、胶囊剂、溶液剂等剂型产品获批上市。其中,洛索洛芬钠口服溶液目前仅有湖南九典制药股份有限公司、山东益康药业股份有限公司2家药企获得生产批文。据中国药品审评中心(CDE)官网最新显示,已有山东益康药业股份有限公司、湖南普道医药技术有限公司、重庆华邦制药有限公司、湖南九典制药股份有限公司、云南先施药业有限公司、南京海纳医药科技股份有限公司、福建汇天生物药业有限公司、江西施美药业股份有限公司、北京远方通达医药技术有限公司、合肥诚志生物制药有限公司、广东万泰科创药业有限公司、湖南先施制药有限公司、海南广升誉制药有限公司、南京海鲸药业股份有限公司、南京易腾药物研究院有限公司、合肥启旸生物医药科技有限公司16家药企申报生产获受理,竞争异常激烈。

据米内网数据显示,2023年洛索洛芬在中国三大终端六大市场销售规模突破20亿元大关,其中,院内市场是主力销售渠道;院外市场(零售药店:城市实体药店+网上药店)则快速增长,2021-2023年分别同比增长35.70%、60.00%、37.29%。

值得注意一提的是,洛索洛芬钠片已被纳入第四批国家集采,中选企业分别是卫材(辽宁)制药、迪沙药业、湖南九典制药,中选价格分别是每片0.276元、0.291元和0.294元。被纳入集采后,洛索洛芬钠口服制剂在抗炎和抗风湿药的市场占比有望进一步提高。

随着老龄化进程加快,国内抗炎药和抗风湿药的需求越来越大,2023年至今已有超过40个国产新品获批,成为市场新的搅局者。洛索洛芬钠口服溶液是湖南九典制药在2023年10月拿下的国内首仿,原研的洛索洛芬钠口服溶液最早于2001年在日本上市,主要用于类风湿关节炎、骨性关节炎、腰痛症、肩关节周围炎、颈肩腕综合征、牙痛,以及手术后、外伤后及拔牙后的消炎和镇痛,亦用于急性上呼吸道炎(包括伴有急性支气管炎的急性上呼吸道炎)的解热和镇痛,截至目前原研产品暂未进入中国市场。

END

免责声明:本文仅作知识交流与分享及科普目的,不涉及商业宣传,不作为相关医疗指导或用药建议。文章如有侵权请联系删除。

OTC2024类器官前沿应用与3D细胞培养论坛圆满落幕,点击图片可查看会后报告,咨询OTC2025类器官论坛请联系:王晨 180 1628 8769

上市批准

2024-05-30

·赛柏蓝

编者按:本文来自米内网,作者未晞;赛柏蓝授权转载,编辑相宜随着老龄化进程加快,国内抗炎药和抗风湿药的需求越来越大,2023年至今已有超过40个国产新品获批,成为市场新的搅局者。01百亿市场稳步回升先声首次夺冠,上药抗压能力强图1:抗炎药和抗风湿药销售规模(单位:万元)在中国公立医疗机构终端,抗炎药和抗风湿药在2013-2019年保持快速增长态势,销售额峰值在2019年达到了183亿元,2020-2021年急降12.94%、8.80%,2022年起恢复正增长,2023年再涨2.25%,该类药物近三年的销售额保持在140亿元水平。表1:2023年抗炎药和抗风湿药TOP5企业情况近三年在中国公立医疗机构终端,抗炎药和抗风湿药龙头企业频繁易主。2021年是江苏恒瑞医药夺冠,市场份额在6%左右;2022年是成都倍特药业突围,市场份额在9%左右;2023年是海南先声药业封王,市场份额在8%左右。值得注意的是,近三年无论龙头如何变换,上药中西制药一直稳守TOP2宝座,抗压能力实属强大。公司的抗炎药和抗风湿药在2022年突破10亿元规模,2023年涨至11.6亿元。0220亿品种领军市场TOP1注射剂急降30%2023年在中国公立医疗机构终端抗炎药和抗风湿药市场,酮咯酸氨丁三醇是唯一一个超20亿品种,羟氯喹、布洛芬、氨基葡萄糖、双氯芬酸钠、艾拉莫德的销售额在10亿元以上。表2:2023年抗炎药和抗风湿药TOP10产品图2:酮咯酸氨丁三醇注射液的销售情况(单位:万元)酮咯酸氨丁三醇注射液是一种解热镇痛抗炎药,常用于手术后镇痛。2021年在中国公立医疗机构终端以19.9亿元的销售额成为了抗炎药和抗风湿药TOP1产品,2022年涨至25.9亿元。2023年4月第八批国采纳入了酮咯酸氨丁三醇注射液,山东新时代药业等4家国内药企中标,受降价影响该产品2023年大跌30.5%。TOP1-TOP5产品排名与2022年相比未有发生变化,塞来昔布胶囊上升1位至TOP6,盐酸氨基葡萄糖片上升3位至TOP7,硫酸氨基葡萄糖胶囊上升9位至TOP10,遗憾的是双氯芬酸钠缓释片在2023年跌出了TOP10榜单。表3:2023年抗炎药和抗风湿药TOP20品牌中销售额正增长的品牌图3:海南先声药业的艾拉莫德片销售情况(单位:万元)海南先声药业的艾拉莫德片是2011年获批的国产1.1类新药,具有抗炎和免疫调节双重功效,主要用于治疗活动性类风湿关节炎。该产品上市以来在中国公立医疗机构终端一直保持快速增长态势,2022年销售额突破10亿元,品牌排名为TOP3,2023年升至12.2亿元,成为了抗炎药和抗风湿药新的TOP1品牌。图4:江苏正大清江制药的盐酸氨基葡萄糖片销售情况(单位:万元)江苏正大清江制药的盐酸氨基葡萄糖片在第三批国采中标,2020-2022年的销售额跌至3亿元水平,2023年大涨57.69%销售额首次突破5亿元,该品牌经历市场洗礼后脱颖而出,绽放新活力。浙江海正药业的硫酸氨基葡萄糖胶囊同样在第三批国采中标,经历了2020-2022年连续暴跌,该品牌的销售额已跌至1亿元级别,2022年退出了TOP20品牌榜单。2023年该品牌大涨38.26%,以1.8亿元销售额重回TOP17品牌。0349个国产新品已顺利入局超10亿产品备战第十批国采随着用药需求增大,越来越多国内药企加入抢食这个百亿市场,米内网数据显示,2023年至今已有49个国产新品(按产品名+生产企业统计)获批上市,华润三九、济川药业、以岭药业、扬子江等国内巨头均有收获。表3:2023年至今获批上市的抗炎药和抗风湿药国产新品洛索洛芬钠口服溶液是湖南九典制药在2023年10月拿下的国内首仿,目前为独家产品。原研的洛索洛芬钠口服溶液最早于2001年在日本上市,主要用于类风湿关节炎、骨性关节炎、腰痛症、肩关节周围炎、颈肩腕综合征、牙痛,以及手术后、外伤后及拔牙后的消炎和镇痛,亦用于急性上呼吸道炎(包括伴有急性支气管炎的急性上呼吸道炎)的解热和镇痛,截至目前原研产品暂未进入中国市场。湖南九典制药针对洛索洛芬已获批了洛索洛芬钠凝胶贴膏、洛索洛芬钠片和洛索洛芬钠口服溶液,洛索洛芬钠贴剂的上市申请正在审评审批中。右酮洛芬氨丁三醇注射液是南京正科医药在2023年5月拿下的国内首仿,目前为独家产品。原研的右酮洛芬氨丁三醇注射液最早于2002年获HMA批准上市,因该药在术后疼痛、急性腰痛及肾绞痛等方面持久的镇痛效果与良好的安全性,在欧洲各成员国获得广泛的临床应用,原研产品暂未进入中国市场。重组人Ⅱ型肿瘤坏死因子受体-抗体融合蛋白注射液是三生国健药业(上海)在2023年3月获批的生物药3.4类新药,目前为独家产品。该产品适应症为中度及重度活动性类风湿关节炎,18岁及18岁以上成人中度及重度斑块状银屑病,以及活动性强直性脊柱炎。近几年,国家集中带量采购持续加码,为市场腾出空间,助力高质量产品实现腾飞。从4+7城市试点开始,第二批、第三批、第四批、第八批国采共纳入了14个抗炎药和抗风湿药(按产品名统计),涉及硫酸氨基葡萄糖胶囊、盐酸氨基葡萄糖胶囊、盐酸氨基葡萄糖片、布洛芬缓释胶囊、布洛芬颗粒、布洛芬片、布洛芬注射液、氟比洛芬酯注射液、洛索洛芬钠片、美洛昔康片、注射用帕瑞昔布钠、塞来昔布胶囊、酮咯酸氨丁三醇注射液、依托考昔片。第十批国采是医药界2024年的重要任务之一,备受市场关注,目前已过评且暂未纳入国采的抗炎药和抗风湿药中,竞争企业(原研+过评)≥5家的产品涉及布洛芬混悬液、双氯芬酸钠缓释片、硫酸羟氯喹片。表4:竞争企业≥5家的产品硫酸羟氯喹片的适应症为类风湿关节炎,青少年慢性关节炎,盘状和系统性红斑狼疮,以及由阳光引发或加剧的皮肤病变。2023年在中国公立医疗机构终端,该产品的销售额已突破14亿元,目前上药中西制药以超过81%的份额领军(已通过一致性评价),原研企业赛诺菲仅占了18%左右。2023年起,江苏知原药业等5家药企的4类仿制上市申请获批并视同过评,若硫酸羟氯喹片最终顺利进入第十批国采,“光脚企业”必将全力出击,新一轮价格激战即将展开。资料来源:米内网数据库END内容沟通:13810174402医药代表交流群扫描下方二维码加入银发经济市场机遇交流群扫描下方二维码加入左下角「关注账号」,右下角「在看」,防止失联

上市批准医药出海申请上市一致性评价

分析

对领域进行一次全面的分析。

登录

或

Eureka LS:

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

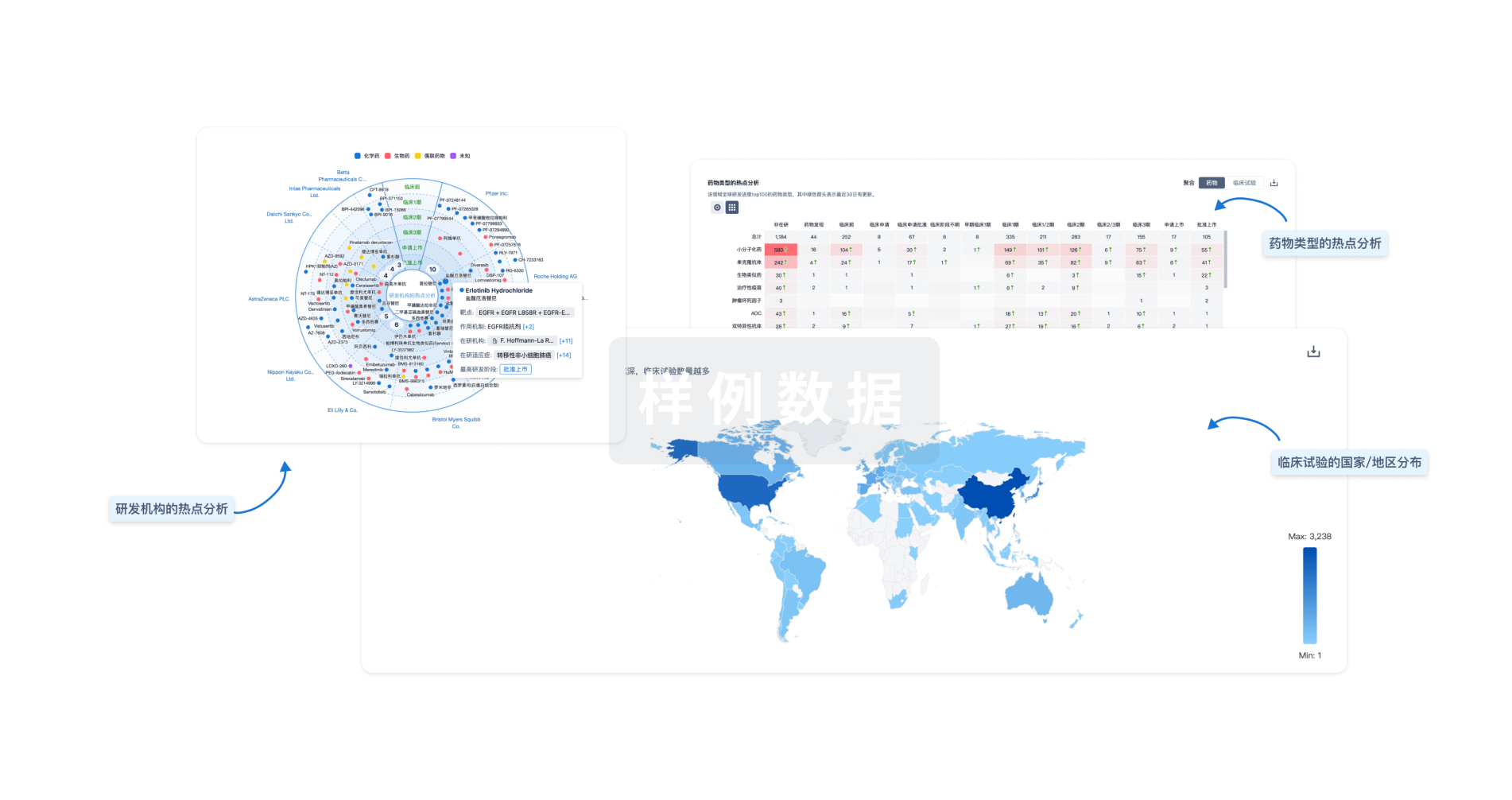

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用