预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

Instituto De SAlud Carlos Iii De Madrid

更新于:2025-05-07

概览

标签

血液及淋巴系统疾病

肿瘤

其他疾病

化学药

通用型CAR-T

自体CAR-T

疾病领域得分

一眼洞穿机构专注的疾病领域

暂无数据

技术平台

公司药物应用最多的技术

暂无数据

靶点

公司最常开发的靶点

暂无数据

| 排名前五的药物类型 | 数量 |

|---|---|

| 自体CAR-T | 1 |

| 通用型CAR-T | 1 |

| 化学药 | 1 |

| 排名前五的靶点 | 数量 |

|---|---|

| JAK x NF-κB | 1 |

| CD19(B淋巴细胞抗原CD19) | 1 |

| BCMA(B细胞成熟蛋白) | 1 |

关联

5

项与 Instituto De SAlud Carlos Iii De Madrid 相关的药物靶点 |

作用机制 CD19调节剂 |

非在研适应症 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 西班牙 |

首次获批日期2021-02-10 |

靶点 |

作用机制 BCMA抑制剂 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床2期 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

作用机制 JAK抑制剂 [+1] |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

298

项与 Instituto De SAlud Carlos Iii De Madrid 相关的临床试验NCT06871059

Effectiveness, Implementation and Spillover Effects of a Culturally Adapted Diabetes Prevention Program in Spanish Primary Care Centers: a Cluster Randomized Hybrid Type II Trial

The ALADIM trial is a hybrid type II effectiveness-implementation cluster-randomized controlled, parallel, two arm, superiority trial. The clusters consist of 10 Primary Care Centers (PCCs) of Mallorca (Balearic Islands, Spain), which are randomly assigned to either the intervention or the control group in a 1:1 ratio. The intervention group (5 PCCs) receives training and supporting material to facilitate the implementation of the adapted DPP and effectively deliver the program over a 12-month period. The control group (5 PCCs) continues providing usual care, in line with standard healthcare practices. Effectiveness outcomes are assessed at participant level according to a cluster-randomized controlled design with data collection at baseline, 6-month and 12-month during the intervention period, and at 18-month follow-up to evaluate mid-term effects post-intervention. Implementation outcomes are assessed at PCC level throughout the study period. Prior to the hybrid trial, the DPP will be culturally and contextually adapted to the Spanish Primary Care setting.

The DPP will be culturally adapted using the Intervention Mapping ADAPT (IM-ADAPT) approach. Simultaneously, the implementation strategy will be designed using the Implementation Mapping approach.

The DPP will be culturally adapted using the Intervention Mapping ADAPT (IM-ADAPT) approach. Simultaneously, the implementation strategy will be designed using the Implementation Mapping approach.

开始日期2025-09-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06901739

New Dietary Intervention Strategies on the Intestinal Microbiota to Improve Mental Health Subjects With Obesity: Therapeutic Potential of a Synbiotic.

Obese individuals are a particularly vulnerable population for mental health problems, especially depression and anxiety. The aim of this study is to evaluate whether the intake of a synbiotic, composed of prebiotics and beneficial intestinal bacterial strains, is capable of producing changes in the gut microbiota and its functionality, improving metabolic and inflammatory parameters, intestinal function and appetite control in patients with obesity and psychological disorders. In addition, the production of neurotransmitters at the level of the gut-brain axis will be studied, as well as mood and quality of life. For this purpose, a prospective, randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled intervention study will be carried out in patients with obesity (BMI=30-40 kg/m2) and symptoms of anxiety and/or depression, or patients with obesity but without these psychological disorders (n=120). The groups will be randomly divided into two groups (n=60) according to the intake of a synbiotic (1 capsule/day composed of bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus and tannin-based phytocomplexes) or its corresponding placebo for 12 weeks. Individualized psychological and nutritional follow-up will be carried out, demographic, lifestyle and mental health variables will be collected, and biological samples will be collected before and after the intervention. In addition, all patients will undergo an assessment of body composition and nutritional status, together with cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, DM2, insulin resistance). Inflammatory parameters (IL6, TNF , IL1b, adiponectin, PAI-1, IL10, resistin, adipsin), antioxidant capacity, intestinal function (zonulin, LPS, occludin, LBP, FABP2/I-FABP, -glucan, Reg3A), satiety, appetite control (Leptin, GLP1, GIP, Ghrelin, PP) and neurotransmitter production (cortisol, dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin) in plasma/serum, urine or saliva using ELISA Kits and Luminex XMAP technology will be analyzed. In addiition, the investigators will perform analysis of genetic markers of inflammatory and metabolic pathways (Nanostring technology), metabolomic profiling (NMR spectroscopy and PLS-DA) in plasma, and both content and diversity of the intestinal microbiota (16S rRNA amplicons, and direct metagenomic sequencing, with Illumina MiSeq technology) in faeces will be evaluated.

Finally, the investigators will study in vitro the mechanism of action of colonic digest on complex cellular models that simulate the gut-brain axis (organ-on-chip model, OoC).

Finally, the investigators will study in vitro the mechanism of action of colonic digest on complex cellular models that simulate the gut-brain axis (organ-on-chip model, OoC).

开始日期2025-04-15 |

NCT06856915

Effects of Home-based Respiratory Muscle Training by Telerehabilitation on Quality of Life, Cardiopulmonary Function, Physical Status and Psychological Status in Individuals with Ischemic Heart Disease

The main objective of the present study is to verify whether respiratory muscle training programme (IMT+EMT; included both inspriratory and expiratory muscles), applied by telerehabilitation, is an effective intervention (versus placebo and versus inspiratory muscle training in isolation (IMT)) in improving quality of life, cardiopulmonary function and physical and psychological state in people with ischemic heart disease. In addition, the aim is to determine whether respiratory muscle training (IMT or IMT+EMT) is effective in enhancing the results obtained by a conventional cardiac rehabilitation programme on the aforementioned variables.

开始日期2025-03-31 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 Instituto De SAlud Carlos Iii De Madrid 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 Instituto De SAlud Carlos Iii De Madrid 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

17,351

项与 Instituto De SAlud Carlos Iii De Madrid 相关的文献(医药)2025-12-31·Cogent Psychology

Relating to a new body: understanding the influence of body compassion and metacognition on body image in breast cancer survivors

作者: Pravettoni, Gabriella ; Baños, Rosa ; Galdón, María José ; Sebri, Valeria ; Herrero, Rocío ; Jiménez-Díaz, Alba

2025-06-01·American Heart Journal

Occult cancer in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism: Rationale, design, and methods of the VaLRIETEs study and the SOME-RIETE trial

Article

作者: Andrade-Ruiz, Henry A ; Bikdeli, Behnood ; Mena-Muñoz, Elisabeth ; Mahe, Isabelle ; de la Red-Bellvis, Gloria ; Marchena-Yglesias, Pablo Javier ; Lopez-Miguel, Patricia ; Lopez-Nuñez, Juan Jose ; Del Molino-Sanz, Fatima ; Fernandez-Reyes, Jose Luis ; Meireles, Jose ; Jou-Segovia, Ines ; Imbalzano, Egidio ; Barca-Hernando, Maria ; Aibar-Gallizo, Jesus ; Lopez-Saez, Juan Bosco ; Portillo-Sanchez, Jose ; Elias-Hernandez, Teresa ; Marcos-Jubilar, Maria ; Marin-Romero, Samira ; Diaz-Brasero, Ana Maria ; Diaz-Pedroche, Carmen ; Mehdipour, Ghazaleh ; Pagan-Escribano, Javier ; Villalobos-Sanchez, Aurora ; Amado-Fernandez, Cristina ; Otalora-Valderrama, Sonia ; Agudo-de Blas, Paloma ; Jara-Palomares, Luis ; Lorenzo-Hernandez, Alicia ; Diaz-Peromingo, Jose Antonio

2025-06-01·Research in Developmental Disabilities

Gut microbiome differences in children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder and effects of probiotic supplementation: A randomized controlled trial

Article

作者: Rojo-Marticella, Meritxell ; Bulló, Mònica ; Canals-Sans, Josefa ; Papandreou, Christopher ; Novau-Ferré, Nil

5

项与 Instituto De SAlud Carlos Iii De Madrid 相关的新闻(医药)2024-06-17

Amarna Therapeutics announces formation of Scientific Advisory Board to support advancement of groundbreaking Nimvec™ AM510 gene therapy against Type 1 Diabetes

Members: Prof. Dr. Colin Dayan, Prof. Dr. Desmond Schatz, Prof. Dr. Didac Mauricio, Dr. Luiza Caramori, Dr. Kei Kishimoto, Prof. Dr. Roberto Mallone, Dr. Sylvaine You.

Leiden, The Netherlands, 17 June 2024 – Amarna Therapeutics, (“Amarna” or “the Company”) a privately-held biotechnology company focused on developing transformative gene therapies for a range of rare and prevalent genetic diseases, including Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM), is pleased to announce the formation of its new Scientific Advisory Board (SAB).The newly established SAB consists of seven distinguished international scientific opinion leaders. These experts bring extensive experience and knowledge in the fields of pre-clinical and clinical development, gene therapy, immunology, endocrinology, and regulatory affairs.

The SAB will leverage its extensive expertise to ensure that Amarna’s groundbreaking Nimvec™ AM510 program meets the highest scientific and regulatory standards. This initiative underscores the company's commitment to pioneering treatments for T1DM and enhancing patient outcomes. The SAB's insights will be pivotal in navigating the complex landscape of clinical trials and regulatory approvals, ultimately accelerating the path to market for this groundbreaking therapy.

“The formation of this Scientific Advisory Board marks a major development step for Amarna as we continue our evolution in becoming a clinical stage gene therapy development company,” said Henk Streefkerk, CEO of Amarna. “We are proud and excited to bring together leading clinicians and scientists from across the world who are dedicated to, and have decades of experience in, the clinical development of novel therapeutics for genetic diseases. We believe their collective expertise will be instrumental in guiding Amarna advancing its lead drug candidate, Nimvec™ AM510, as we work to optimize its potential to transform the treatment of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and a range of other prevalent debilitating genetic disorders.”

The members of the Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) are as follows:

Colin Dayan, MA MBBS, FRCP, PhD, is Professor of Clinical Diabetes and Metabolism at Cardiff University School of Medicine, in Cardiff (UK), Senior Clinical Researcher at the University of Oxford and Director at the Cardiff Joint Research Office. His focus lies mainly on translational research in immunopathology of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, clinical trials on peptide immunotherapy and nanoparticles in T1DM.

Desmond Schatz, MD, PhD, is Professor of Pediatrics, Medical Director of the Diabetes Institute, and Medical Director of the Clinical Research Center, at the University of Florida, and served as President of Science and Medicine of the American Diabetes Association (2016). Dr. Schatz has been involved in Type 1 diabetes research since the mid 1980’s and has published over 400 manuscripts, the majority related to the prediction, natural history, genetics, immunopathogenesis and prevention of the disease, as well as the management of children and adolescents with Type 1 diabetes.

Didac Mauricio, MD, PhD, is Director of the Department of Endocrinology & Nutrition, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona, and Professor with the Faculty of Medicine, University of Vic & Central University of Catalonia (UVic/UCC). He is leading the Diabetes Research Group at his current institution and has recently been appointed Scientific Director of the CIBER of Diabetes and Associated Metabolic diseases (CIBERDEM), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Ministry of Science and Innovation), in Spain.

Luiza Caramori, MD, MSc, PhD, is a Staff Physician at the Institute of Endocrinology and Metabolism at Cleveland Clinic Foundation and at the Department of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland, Ohio (USA) and an Adjunct Associate Professor at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN (USA). Dr. Caramori’s is a physician-scientist with 25+ years research experience, whose main research interests include studies on the relationships between kidney structure and function in type 1 diabetes, early molecular and structural predictors of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) in patients with type 1 diabetes, and clinical trials studying repurposed and new drugs for the prevention and treatment of DKD both in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Kei Kishimoto, PhD, is a highly accomplished immunologist and drug developer with over 30 years of experience in biopharma. He was most recently Chief Scientific Officer of Selecta Biosciences, where he led development of an immune tolerance technology that was successfully validated in Phase 3 clinical trials. Prior to joining Selecta, he was Vice President of Research at Momenta Pharmaceuticals and Senior Director Inflammation at Millennium Pharmaceuticals. His expertise is focused on immunology, immune tolerance, autoimmune diseases, vaccines, immunogenicity and gene therapy.

Kei Roberto Mallone, MD, PhD, is Professor and Hospital Physician in Clinical Immunology and Diabetology at Paris Cité University - Cochin Hospital and Research Director at INSERM U1016 Cochin Institute in Paris, France and at the Indiana Biosciences Research Institute (IBRI) in Indianapolis (USA). His research spans from preclinical studies with human samples and mouse models to clinical trials. It focuses on autoimmune T cells and beta-cell vulnerability and the understanding of type 1 diabetes mechanisms to develop T-cell-based biomarkers and therapeutics aimed at blunting T-cell aggressiveness and enhancing beta-cell resilience.

Sylvaine You, MD, PhD, is a distinguished researcher specializing in the immune mechanisms driving type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and the development of therapeutic strategies. She is Research Director at Cochin Institute (INSERM) in Paris, France, focuses on T-cell Tolerance, Biomarkers and Therapies in type 1 Diabetes. Additionally, she co-leads a research team at the Indiana Biosciences Research Institute (IBRI), exploring the mechanisms that fail to keep autoreactive T lymphocytes inoffensive and make the beta cells more visible and vulnerable to an autoimmune attack.

=== E N D S ===

About Type 1 Diabetes MellitusType 1 Diabetes is a debilitating disease occurring in millions of patients globally, with rising incidences each year, where despite advancements in therapy the life expectancy remains lower than the general population. Diabetes is an autoimmune disease where self-reactive T lymphocytes selectively attack and destroy insulin-producing β cells lodged within the pancreas, leaving the patient unable to maintain glucose homeostasis. Proinsulin (PI) is the primary self-antigen involved in the autoimmune β cell destruction. To date, Type 1 Diabetes cannot be cured, and the glucose homeostasis can be more or less maintained in patients by daily insulin injections. Although Diabetes is seen as a manageable disease nowadays, secondary complications of the current therapy are considerable and lead to significant morbidity and mortality. Using Nimvec™ AM510 we intend to restore the immune tolerance to proinsulin and potentially cure the patients.

About Nimvec™ AM510The development of AM510 is based on our proprietary NimvecTM platform, which has demonstrated exceptional promise in preclinical studies. Unlike other gene therapies that induce a strong immune response, limiting the possibility for repeat dosing and efficacy, NimvecTM does not trigger such responses. Instead, it moderates the immune system to induce tolerance, making it an ideal vehicle for our therapeutic approach. Our preclinical data with Nimvec™ AM510 showcases its protective effects in delaying the onset of hyperglycemia and preventing the development of T1DM in relevant animal models.

About AmarnaAmarna Therapeutics has developed a groundbreaking non-immunogenic viral platform NimvecTM to deliver any transgene of choice into humans. This platform shows exceptional promise in preclinical studies for delivering treatments, potential cures, and disease prevention globally. Amarna is advancing a pipeline of transformative gene therapies for a range of rare and prevalent diseases, including monogenetic indications, autoimmune diseases and chronic inflammation. The lead program Nimvec™ AM510 is being developed for the treatment of patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Follow up programs include Multiple Sclerosis, Age-related Macular Degeneration, and Hemophilia.

More information on www.amarnatherapeutics.com

Follow us on LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/company/amarna-therapeutics-b.v.

For further inquiries please contact:

Amarna TherapeuticsHenk Streefkerk, CEOE-mail: info@amarnatherapeutics.com

LifeSpring Life Sciences Communication, AmsterdamLéon MelensTel: +31 6 538 16 427E-mail: lmelens@lifespring.nl

临床3期高管变更

2024-06-17

Amarna Therapeutics announces formation of Scientific Advisory Board to support advancement of groundbreaking Nimvec™ AM510 gene therapy against Type 1 Diabetes

Members: Prof. Dr. Colin Dayan, Prof. Dr. Desmond Schatz, Prof. Dr. Didac Mauricio, Dr. Luiza Caramori, Dr. Kei Kishimoto, Prof. Dr. Roberto Mallone, Dr. Sylvaine You.

Leiden, The Netherlands, 17 June 2024 – Amarna Therapeutics, (“Amarna” or “the Company”) a privately-held biotechnology company focused on developing transformative gene therapies for a range of rare and prevalent genetic diseases, including Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM), is pleased to announce the formation of its new Scientific Advisory Board (SAB).

The newly established SAB consists of seven distinguished international scientific opinion leaders. These experts bring extensive experience and knowledge in the fields of pre-clinical and clinical development, gene therapy, immunology, endocrinology, and regulatory affairs.

The SAB will leverage its extensive expertise to ensure that Amarna’s groundbreaking Nimvec™ AM510 program meets the highest scientific and regulatory standards. This initiative underscores the company's commitment to pioneering treatments for T1DM and enhancing patient outcomes. The SAB's insights will be pivotal in navigating the complex landscape of clinical trials and regulatory approvals, ultimately accelerating the path to market for this groundbreaking therapy.

“The formation of this Scientific Advisory Board marks a major development step for Amarna as we continue our evolution in becoming a clinical stage gene therapy development company,” said Henk Streefkerk, CEO of Amarna. “We are proud and excited to bring together leading clinicians and scientists from across the world who are dedicated to, and have decades of experience in, the clinical development of novel therapeutics for genetic diseases. We believe their collective expertise will be instrumental in guiding Amarna advancing its lead drug candidate, Nimvec™ AM510, as we work to optimize its potential to transform the treatment of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and a range of other prevalent debilitating genetic disorders.”

The members of the Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) are as follows:

Colin Dayan, MA MBBS, FRCP, PhD, is Professor of Clinical Diabetes and Metabolism at Cardiff University School of Medicine, in Cardiff (UK), Senior Clinical Researcher at the University of Oxford and Director at the Cardiff Joint Research Office. His focus lies mainly on translational research in immunopathology of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, clinical trials on peptide immunotherapy and nanoparticles in T1DM.

Desmond Schatz, MD, PhD, is Professor of Pediatrics, Medical Director of the Diabetes Institute, and Medical Director of the Clinical Research Center, at the University of Florida, and served as President of Science and Medicine of the American Diabetes Association (2016). Dr. Schatz has been involved in Type 1 diabetes research since the mid 1980’s and has published over 400 manuscripts, the majority related to the prediction, natural history, genetics, immunopathogenesis and prevention of the disease, as well as the management of children and adolescents with Type 1 diabetes.

Didac Mauricio, MD, PhD, is Director of the Department of Endocrinology & Nutrition, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona, and Professor with the Faculty of Medicine, University of Vic & Central University of Catalonia (UVic/UCC). He is leading the Diabetes Research Group at his current institution and has recently been appointed Scientific Director of the CIBER of Diabetes and Associated Metabolic diseases (CIBERDEM), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Ministry of Science and Innovation), in Spain.

Luiza Caramori, MD, MSc, PhD, is a Staff Physician at the Institute of Endocrinology and Metabolism at Cleveland Clinic Foundation and at the Department of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland, Ohio (USA) and an Adjunct Associate Professor at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN (USA). Dr. Caramori’s is a physician-scientist with 25+ years research experience, whose main research interests include studies on the relationships between kidney structure and function in type 1 diabetes, early molecular and structural predictors of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) in patients with type 1 diabetes, and clinical trials studying repurposed and new drugs for the prevention and treatment of DKD both in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Kei Kishimoto, PhD, is a highly accomplished immunologist and drug developer with over 30 years of experience in biopharma. He was most recently Chief Scientific Officer of Selecta Biosciences, where he led development of an immune tolerance technology that was successfully validated in Phase 3 clinical trials. Prior to joining Selecta, he was Vice President of Research at Momenta Pharmaceuticals and Senior Director Inflammation at Millennium Pharmaceuticals. His expertise is focused on immunology, immune tolerance, autoimmune diseases, vaccines, immunogenicity and gene therapy.

KeiRoberto Mallone, MD, PhD, is Professor and Hospital Physician in Clinical Immunology and Diabetology at Paris Cité University - Cochin Hospital and Research Director at INSERM U1016 Cochin Institute in Paris, France and at the Indiana Biosciences Research Institute (IBRI) in Indianapolis (USA). His research spans from preclinical studies with human samples and mouse models to clinical trials. It focuses on autoimmune T cells and beta-cell vulnerability and the understanding of type 1 diabetes mechanisms to develop T-cell-based biomarkers and therapeutics aimed at blunting T-cell aggressiveness and enhancing beta-cell resilience.

Sylvaine You, MD, PhD, is a distinguished researcher specializing in the immune mechanisms driving type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and the development of therapeutic strategies. She is Research Director at Cochin Institute (INSERM) in Paris, France, focuses on T-cell Tolerance, Biomarkers and Therapies in type 1 Diabetes. Additionally, she co-leads a research team at the Indiana Biosciences Research Institute (IBRI), exploring the mechanisms that fail to keep autoreactive T lymphocytes inoffensive and make the beta cells more visible and vulnerable to an autoimmune attack.

=== E N D S ===

About Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

Type 1 Diabetes is a debilitating disease occurring in millions of patients globally, with rising incidences each year, where despite advancements in therapy the life expectancy remains lower than the general population. Diabetes is an autoimmune disease where self-reactive T lymphocytes selectively attack and destroy insulin-producing β cells lodged within the pancreas, leaving the patient unable to maintain glucose homeostasis. Proinsulin (PI) is the primary self-antigen involved in the autoimmune β cell destruction. To date, Type 1 Diabetes cannot be cured, and the glucose homeostasis can be more or less maintained in patients by daily insulin injections. Although Diabetes is seen as a manageable disease nowadays, secondary complications of the current therapy are considerable and lead to significant morbidity and mortality. Using Nimvec™ AM510 we intend to restore the immune tolerance to proinsulin and potentially cure the patients.

About Nimvec™ AM510

The development of AM510 is based on our proprietary NimvecTM platform, which has demonstrated exceptional promise in preclinical studies. Unlike other gene therapies that induce a strong immune response, limiting the possibility for repeat dosing and efficacy, NimvecTM does not trigger such responses. Instead, it moderates the immune system to induce tolerance, making it an ideal vehicle for our therapeutic approach. Our preclinical data with Nimvec™ AM510 showcases its protective effects in delaying the onset of hyperglycemia and preventing the development of T1DM in relevant animal models.

About Amarna

Amarna Therapeutics has developed a groundbreaking non-immunogenic viral platform NimvecTM to deliver any transgene of choice into humans. This platform shows exceptional promise in preclinical studies for delivering treatments, potential cures, and disease prevention globally. Amarna is advancing a pipeline of transformative gene therapies for a range of rare and prevalent diseases, including monogenetic indications, autoimmune diseases and chronic inflammation. The lead program Nimvec™ AM510 is being developed for the treatment of patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Follow up programs include Multiple Sclerosis, Age-related Macular Degeneration, and Hemophilia.

More information on

Follow us on LinkedIn

.

For further inquiries please contact:

Amarna Therapeutics

Henk Streefkerk, CEO

E-mail: info@amarnatherapeutics.com

LifeSpring Life Sciences Communication, Amsterdam

Léon Melens

Tel: +31 6 538 16 427

E-mail: lmelens@lifespring.nl

临床3期高管变更

2023-11-08

With more than $35 million invested across 800 research projects, the ABTA is at the forefront of driving progress and seeding hope for life-changing treatments and care for brain tumor patients.

CHICAGO, Nov. 8, 2023 /PRNewswire/ -- The American Brain Tumor Association (ABTA) today announced the funding of $1.37 million towards 23 new research grants to advance brain tumor science and treatments, across all brain tumor types and ages. Dedicated to advancing the field of neuro-oncology and accelerating the discovery of life-saving treatments, the ABTA is proud to have invested more than $35 million, to approximately 700 researchers and 800 projects, to date.

Continue Reading

"Throughout our 50-year history, the ABTA has provided vital seed money to fund collaborative and high-risk, high-reward research grants which have contributed to significant breakthroughs in treating brain tumors by many of the country's leading researchers," said Nicole Willmarth, Ph.D., ABTA's chief mission officer. "We are excited to empower a new class of grant recipients whose bold visions have the potential to unlock new opportunities in the fight against brain tumors."

ABTA's high-risk, high-reward research grants have contributed to significant breakthroughs in treating brain tumors.

Post this

This year's slate of research projects investigates biomarkers, DNA damage and repair mechanisms, gene therapies, and more, across adult and pediatric primary brain tumors and metastatic brain cancers.

The ABTA congratulates the 2023 grant recipients listed below. To learn more about ABTA grant recipients and their research projects, visit .

Research Collaboration Grants are two-year, $200,000 grants awarded for multi-investigator and multi-institutional brain tumor collaborative research projects. They are intended to promote team science, streamlining, and accelerating research progress.

Federico Gaiti, PhD—University Health Network, Canada

Gelareh Zadeh, MD, PhD, FRCSC, FAANS—University of Toronto, Canada

Oliver Jonas, PhD—Brigham and Women's Hospital, Massachusetts

Shawn Hervey-Jumper, MD—University of California, San Francisco, California

Derek Wainwright, PhD—Loyola University of Chicago, Illinois

Pilar Sanchez-Gomez, PhD—Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain

Basic Research Fellowships are two-year, $100,000 grants awarded to post-doctoral fellows who are mentored by established and nationally recognized experts in the neuro-oncology field.

Charuta Furey, MD—Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph Medical Center, Arizona

Juyeun Lee, PhD, DVM—Cleveland Clinic, Ohio

Rakesh Trivedi, PhD—MD Anderson Cancer Center, Texas

Discovery Grants are one-year, $50,000 grants supporting high-risk, high-reward innovative approaches that hold potential to change current diagnostic or treatment standards of care.

Theresa Barberi, PhD—Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Maryland

Defne Bayik, PhD—Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center/University of Miami Health Systems, Florida

Phedias Diamandis, MD, PhD—University Health Network, Canada

Siddharthra Mitra, PhD—University of Colorado Denver, Colorado

Allegra Petti, PhD—Massachusetts General Hospital, Massachusetts

Soma Sengupta, MD, PhD—University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Daniel Silver, PhD—Cleveland Clinic, Ohio

Elizabeth Sweeney, PhD—The George Washington University, District of Columbia

Nehalkumar Thakor, PhD—The University of Lethbridge, Canada

Medical Student Summer Fellowships are three-month, $3,000 grants awarded to medical students to conduct brain tumor research projects under the guidance of neuro-oncology experts. Through these grants, the ABTA seeks to encourage physician-scientists to enter and remain in the brain tumor field.

Michael Chang, BS—Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Maryland

Himanshu Dashora, BS—Cleveland Clinic, Ohio

Jakub Jarmula, BA—Cleveland Clinic, Ohio

Jenna Koenig, BS—Indiana University, Indiana

Jayson Nelson, BS—The University of Utah, Utah

Minh Nguyen, BS—University of California, San Francisco, California

Gabrielle Price, MSc—Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York

Sangami Pugazenthi, BA—Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri

Awarding of these grants would not be possible without the incredible support of our donors and our partner organizations including the Joel A. Gingras Memorial Foundation, Southeastern Brain Tumor Foundation, Brain Up, Brain Tumor Foundation of Canada, Tap Cancer Out, Gladiator Project and StacheStrong.

The ABTA is now accepting applications for its 2024 Research Collaboration Grants, Discovery Grants, Basic Research Fellowships, and Jack and Fay Netchin Medical Student Summer Fellowships. For more information on grant opportunities and deadlines, visit .

About the American Brain Tumor Association

Founded in 1973, the American Brain Tumor Association provides comprehensive resources to support the complex needs of brain tumor patients and caregivers, across all ages and tumor types, as well as the critical funding of research in the pursuit of breakthroughs in brain tumor diagnoses, treatments, and care. To learn more, visit, abta.org or call 800-886-ABTA (2282).

SOURCE American Brain Tumor Association

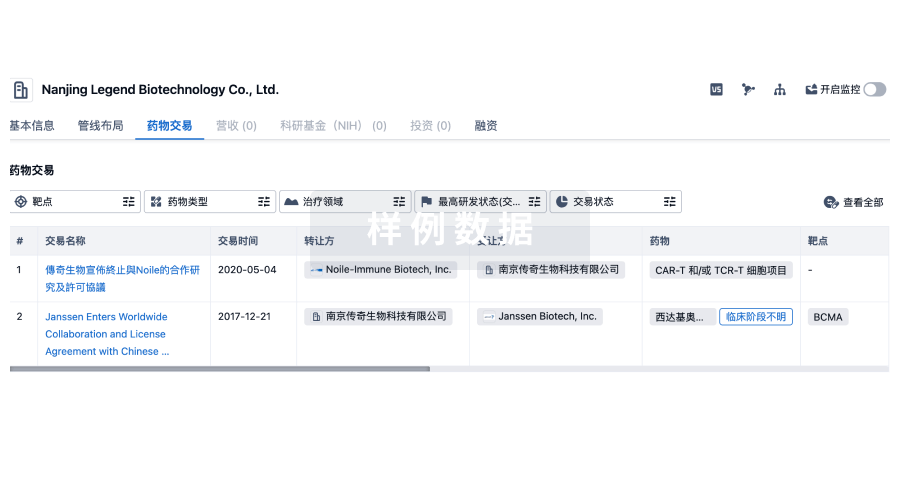

100 项与 Instituto De SAlud Carlos Iii De Madrid 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

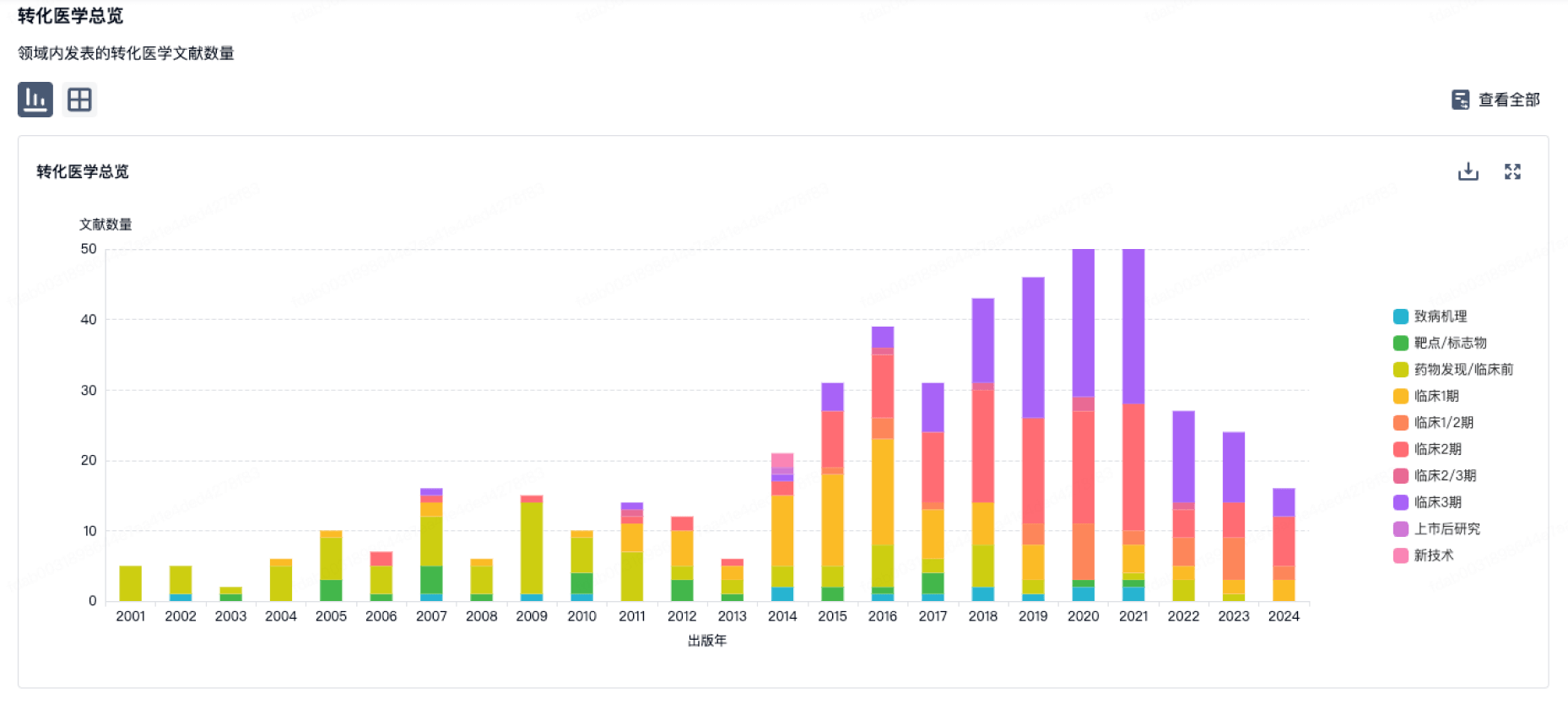

100 项与 Instituto De SAlud Carlos Iii De Madrid 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

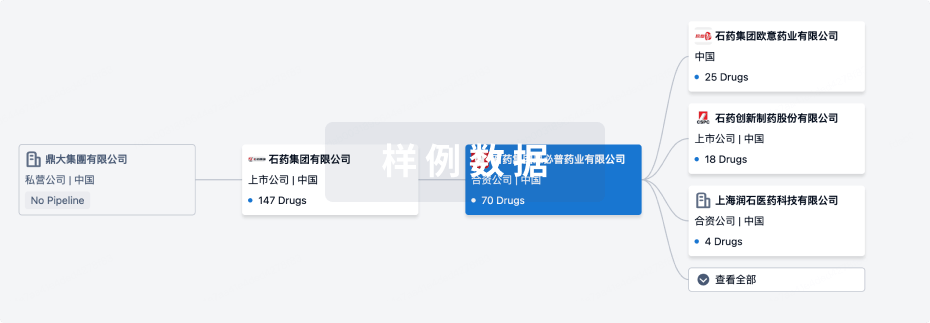

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2025年11月12日管线快照

管线布局中药物为当前组织机构及其子机构作为药物机构进行统计,早期临床1期并入临床1期,临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

临床前

1

1

临床2期

批准上市

1

2

其他

登录后查看更多信息

当前项目

| 药物(靶点) | 适应症 | 全球最高研发状态 |

|---|---|---|

法基奥仑赛 ( CD19 ) | 急性淋巴细胞白血病 更多 | 批准上市 |

Cesnicabtagene Autoleucel ( BCMA ) | 难治性多发性骨髓瘤 更多 | 临床2期 |

BMS-345541 ( JAK x NF-κB ) | 骨髓纤维化 更多 | 临床前 |

Anti-CD30 CAR T-cells(Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute) ( CD30 ) | 复发性T细胞淋巴瘤 更多 | 无进展 |

L-165041 ( PPARδ ) | 肥胖 更多 | 无进展 |

登录后查看更多信息

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

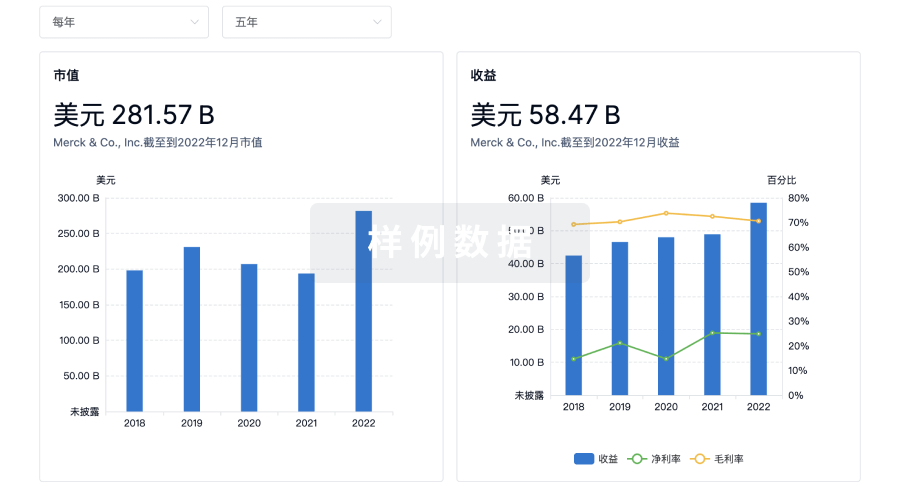

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

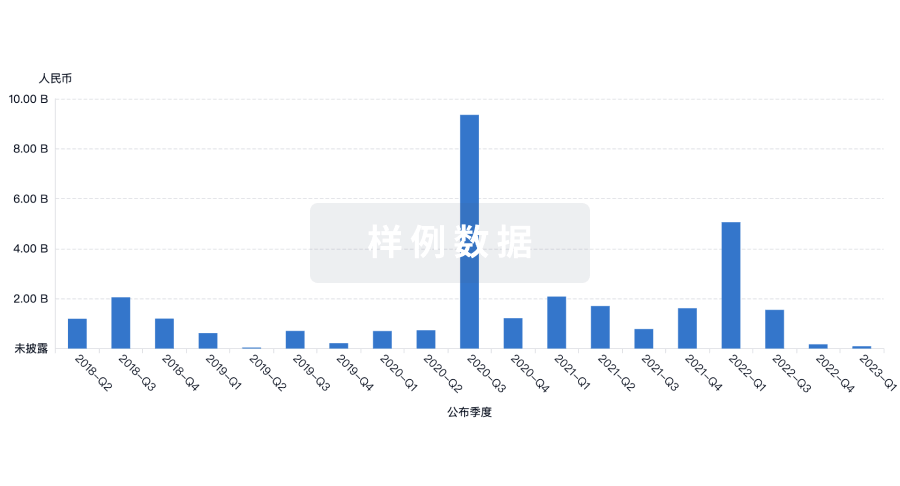

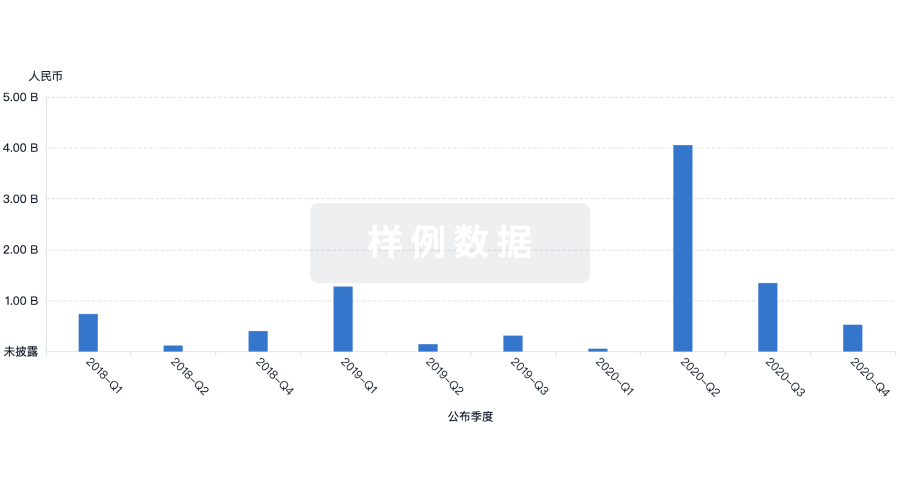

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用