预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

Hyman, Phelps & McNamara PC

更新于:2025-05-07

概览

关联

1

项与 Hyman, Phelps & McNamara PC 相关的临床试验NCT03680365

Your Voice; Impact of DMD. A Qualitative Assessment of the Impact of DMD on the Lives of Families

The purpose of this study is to improve the understanding of the treatment goals that a person with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) or the caregiver may be most interested in, based on the severity of the person's disease. Data will be collected by online survey when the participant accepts the study invitation ("RSVP questionnaire") and telephone interview on the functional burden and self-identified treatment goals from the perspective of people with DMD and their caregivers. Interviews will be analyzed to help identify things important to Duchenne families to measure in clinical trials and to inform the selection of key concepts of interest and development of future clinical outcome measures, including observer reported outcomes/patient reported outcomes. The study will be conducted in the United States and will enroll between 45 and 120 participants 11 years or older living with DMD as well as their caregivers. The time commitment for the online survey and the telephone interview is about one hour. It is anticipated that the entire study will be completed within one year.

开始日期2018-09-20 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 Hyman, Phelps & McNamara PC 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 Hyman, Phelps & McNamara PC 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

3

项与 Hyman, Phelps & McNamara PC 相关的文献(医药)1992-01-01·Food Reviews International

Quantitative risk assessment, food chemicals, and a healthy diet

作者: Scarlett, Thomas

JAMA Internal Medicine

Xuebijing injection for the treatment of sepsis: what would a path to FDA approval look like?

作者: Unger, Ellis F. ; Clissold, David B.

New England Journal of Medicine

Contaminated dietary supplements

作者: Carvajal, Ricardo

3

项与 Hyman, Phelps & McNamara PC 相关的新闻(医药)2025-04-17

The Food and Drug Administrations attempt to increase regulatory scrutiny over laboratory developed tests appears to be dead, much to the relief of clinical labs.The FDA is unlikely to appeal the March 31 federal court order that set aside a final rule asserting the agencys jurisdiction over LDTs, attorneys who handle regulatory matters said in interviews.The possibility that Congress could still overhaul the regulatory framework for diagnostic testing lives on, though any new legislative effort would likely take time, as the issue has not been a top priority for lawmakers.The LDT concept is sort of like a vampire, and it's risen many times in the past, said Jeff Gibbs, a director at the law firm Hyman, Phelps & McNamara, which represented the Association for Molecular Pathology in the case against the FDA. This isn't quite the stake in the heart.Intended to strengthen oversight of labs that develop, manufacture and use their own diagnostic tests, the FDAs final rule would have regulated LDTs as medical devices. Over four years, it would have phased in requirements such as adverse event reporting, premarket review, registration, labeling and other provisions.Concerned that the high costs of complying with the rule would force labs to discontinue some test services, to the detriment of patients, the American Clinical Laboratory Association and AMP sued to stop the FDA from enforcing the regulation and prevailed. Judge Sean Jordan of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas vacated the rule, which would have taken effect next month.Most labs, whether in larger hospitals that perform complex tests or community settings focused on routine care, use LDTs to meet specific clinical needs, where commercial in vitro diagnostic tests are unavailable. Sheldon Campbell, a professor at the Yale School of Medicine, said LDTs are any test thats not done exactly the way the FDA approved it.With implementation of the FDA rule halted, those labs can basically keep going with the staff they've got, said Campbell, who is director of laboratories for the VA Connecticut Healthcare System. This is a real benefit for patients.LDTs are regulated under the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments program, as established by Congress. The FDA, which regulates tests that it authorizes for use as medical devices, for decades followed an enforcement discretion policy toward LDTs.The FDAs viewIn moving to expand its requirements for LDTs, the FDA argued that more active oversight was needed due to greater risks associated with modern versions of the tests.The FDA is aware of numerous examples of potentially inaccurate, unsafe, ineffective or poor quality IVDs offered as LDTs that caused or may have caused patient harm, including tests used to select cancer treatment, aid in the diagnosis of COVID-19, aid in the management of patients with rare diseases and identify a patients risk of cancer, the agency said last year when it announced the final rule.Then-FDA Commissioner Robert Califf said the agency could not stand by while Americans relied on the widely used tests without assurance that they work.Campbell and others say LDTs already receive significant scrutiny under CLIA, a comprehensive framework through which issues with LDTs can be addressed. Doing it incrementally and evolutionarily within the CLIA framework is a more sensible approach than creating a second entire regulatory apparatus for laboratories, Campbell said.The U.S. district court, which remanded the matter to newly confirmed Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., concluded the rule exceeded the FDAs authority under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938. The opinion cited the Supreme Courts decision last year in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo in finding the FDA lacked the statutory authority to regulate LDTs as devices.Despite the FDAs determination to increase oversight of the tests, attorneys said they dont think the agency will appeal the district courts decision, though it could.Certainly the government has the right to appeal this and can do that, said Chad Landmon, attorney at the Polsinelli law firm. But a lot of people have thought, and myself included, that the more likely outcome is that they won't appeal, and they will just let this die for now, until either activity from Congress or the next administration four years from now.The FDA did not respond to an inquiry from MedTech Dive on whether it would appeal the case.Any comment or other response to the courts opinion, such as a formal revoking of the final rule, could be slowed by recent cuts to FDA staff, including in the communications department, Landmon said, adding, I do expect it's such an important issue that we'd likely get some sort of statement or clarification about it.The LDT concept is sort of like a vampire, and it's risen many times in the past. This isn't quite the stake in the heart.Jeff GibbsHyman, Phelps & McNamara directorUnder the new Republican administration, the FDA might not challenge the court decision, given the rules unpopularity with industry, said Ben Wolf, a partner at the law firm Alston & Bird. I would say, for now, industry should feel pretty good about where things stand, as far as not having to come into compliance with the FDA requirements, he said.As the FDA considers its next steps, one area to watch is whether the regulator begins actions toward products previously not targeted for active enforcement. They may choose to put their enforcement dollars elsewhere, but it certainly is a possibility, Wolf said.As for the work that labs put into preparing for the FDAs rule before it was halted, its not that it was a completely useless effort, said Yales Campbell, because labs continuously evaluate their test lists.The case for reformZach Rothstein, executive director of AdvaMedDx, the diagnostics division of medical device trade group AdvaMed, said having dual regulatory roles one at CMS and one at the FDA for what amounts to the same product is not a good use of the government's resources.Given the questions raised by the courts decision, it is in the interest of everyone for Congress to act to finally decide how, as a country, we should treat LDTs, because right now you can have two different tests for the same patient regulated by two different regulatory programs, Rothstein said. Thats not an efficient way for us to review these products, and its also not in the publics best interest.Legislation called the Verifying Accurate, Leading-edge IVCT Development Act that sought to reform the regulatory framework for IVDs failed to gain traction in Congress in recent years despite multiple attempts to advance the bill.Given the questions raised by the courts decision, it is in the interest of everyone for Congress to act to finally decide how, as a country, we should treat LDTs.“Zach RothsteinAdvaMedDx executive directorSeveral attorneys said that while diagnostics regulatory reform is needed, they don't anticipate the current Congress, with both a Republican-controlled House and Senate, will pass legislation on LDTs anytime soon. For one thing, the VALID Acts Republican sponsor, Larry Bucshon of Indiana, retired from the House in January.State regulators could step in to help fill the void, said Matt Wetzel, a partner at the Goodwin law firm. He noted New York and Washington already have the infrastructure for regulating many aspects of lab operations. The regulatory compliance I don't think goes away, Wetzel said. I think we're going to continue to see that as a significant cost for companies.At some point, however, a renewed legislative effort to modernize regulation of diagnostic testing and clarify FDAs role in LDT oversight is likely, attorneys said.The subject of whether LDTs should be regulated is one that I don't think vanishes. Its now a question of congressional action, rather than FDA, said Hyman, Phelps Gibbs. Barring a successful appeal, the battle shifts completely to Congress. '

2025-04-07

“This is like the flat Earthers taking over NASA,” Janet Woodcock, M.D., said about the current FDA.\n As President Donald Trump’s massive overhaul of federal agencies continues, several former FDA officials spoke about the potential ramifications for drug reviews and provided a look inside current FDA conditions.“Leadership in the agency’s been decapitated, and I think that was somewhat deliberate,” Janet Woodcock, M.D., former acting FDA commissioner and former principal deputy commissioner of food and drugs, said during an April 7 session of the Biopharma Congress.The panel—titled “The Future of FDA: Where Do We Go From Here”—was part of an event hosted by Prevision Policy and Friends of Cancer Research in Washington, D.C.Woodcock, who retired from the agency in February 2024, was joined by two other former FDA officials: Jeff Shuren, M.D., longtime director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH), and Frank Sasinowski, who joined the FDA in 1983 as regulatory counsel and helped establish several modern drug laws, such as the Orphan Drug law. Sasinowski is currently the director of Hyman, Phelps & McNamara, a law firm that specializes in FDA practices. \'A slow-moving catastrophe\' Since Trump took office again, his administration has taken the ax to federal health agencies, ousting thousands of workers and numerous leaders.Notably, Peter Marks, M.D., Ph.D., the former leader of the agency\'s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), resigned late last month. A few days after his resignation, reports broke that new FDA Commissioner Marty Makary, M.D., signed off on Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) head Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s efforts to push him out. Marks had been targeted by RFK Jr. over his approach to vaccines at the CBER, according to Politico. While the broader cuts are ostensibly designed to save cash and increase efficiency, Woodcock doesn’t see the logic in the changes—and she believes the targeted removal of health agency leaders will have catastrophic consequences for drug development.“I don\'t know what the administration\'s rationale for all these cuts were,” said Woodcock, who spent more than 38 years at the FDA. “For example, CBER was about 70% funded by user fees,” she explained. “Therefore, if you ran a pro rata calculation, you\'d only be cutting out of the 30% that was paid for by taxpayers a month.”Woodcock also said the claim that the cuts made won’t impact drug reviews is a “naive conception.”When explaining FDA reviews, Woodcock detailed routine disputes between different disciplines at the agency, noting that varying opinions arise “because there\'s a lot of uncertainty in development of medical products.” Supervisors and leaders generally help quell these disagreements, hearing out all sides and determining the best course of action.“So, I would expect that you\'ll see that you\'ll see mysterious slowdowns and you won\'t know what it\'s about, but it\'s about the agency doesn\'t have any more smooth mechanism to sort out all these disputes,” Woodcock said.The former agency leader compared the current FDA restructuring to retaining only doctors at a hospital, while letting go of all nurses and phlebotomists.“Doctors can\'t just walk in and perform surgery all by themselves,” she said. “The reviewer is the same.”As an example, she pointed to the “timekeeper” position at the FDA, or those who are responsible for recording and maintaining data related to employee time worked and taken off, travel plans, payments and reimbursements.“If you don\'t get paid because there are no timekeepers there, it may cause you to have second thoughts about your job,” she explained.“There seems to be a belief that the people at FDA invented all this paperwork,” the former FDA official continued. “No, you know why this paperwork is there? ... To prevent waste, fraud and abuse.”Shuren, who retired from his spot leading the FDA’s CDRH in 2024, said last week that the recent loss of 3,500 full-time positions would definitely impact the pace of the center’s work.“It would not be surprising if we saw longer review times, at least in the near term,” Shuren said. For the time being, the panelists said the agency\'s attention will remain centered on clinical trials, but those efforts will dwindle as resources and workers also decrease.“You’re not going to see everything come to a stop in the actual review of documents and development programs,” Woodcock explained. “But the whole apparatus to get a drug on the market, a lot of that is missing, and you\'re going to see mistakes.”“So, I would expect this is a slow-moving catastrophe, not an immediate catastrophe,” she said in summation.Already, the FDA has missed its deadline for deciding on approval of Novavax’s COVID-19 shot.Novavax expected to hear back from the FDA about a full, traditional approval for its protein-based COVID-19 vaccine by April 1. Instead, senior leaders at the FDA said they need more data, The Wall Street Journal first reported.Novavax said in a statement that the company “had responded to all of the FDA’s information requests” and felt its application was ready for approval.Rare disease drug developers may be hit harder The restructuring will have a “disproportionate effect” on rare disease development, according to Sasinowski, who cited the role that technical supervisors have in resolving internal disagreements.“If you lose that kind of granularity, you lose the ability to move forward,” he explained, emphasizing the greater need for more flexibility and special pathways, such as the accelerated approval pathway, in rare disease drug development.Sasinowski wondered who would develop new guidelines as the fate of the Office of Regulatory Policy and Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) remain uncertain.“I could go through a whole list of whole communities of rare disease, fellow Americans who have benefited because of the guidance documents that CDER was able to promulgate,” Sasinowski said.\'A zombie movie set\': A look inside the current FDA Under Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency, the federal government plans on terminating 676 leases, including several FDA sites.Meanwhile, HHS’ RFK. Jr. shared plans to downsize the agency—which houses the FDA—by 20,000 staff members. A few days later, he said about 2,000 of the job cuts were done in error, adding that reinstatements were \"always part of the plan.\"“The campus looks like a zombie movie set, with cars parked on every inch of grass available and card tables set up in the halls so that people have some place to put their laptop to work,” Sasinowski said during the Biopharma Congress panel.“Morale is … absent,” Woodcock added. “Because, of course, people have been treated very disrespectfully.”Despite this, some FDA workers remain with the agency, something Woodcock credits to their dedication to serving the agency’s mission, which is ensuring that safe and effective products are available to Americans.“They want to keep doing that,” Woodcock said. “However, I will say, because of some of the cuts, it\'s going to be increasingly difficult over time for people to function.” “Even in the best of times, you lose people—there\'s always attrition,” Shuren added, noting that the agency has worked to foster an environment where attrition is low. “We want people to stay. We know how disruptive it is when people do leave.”“And unless you have the mechanisms to invest not only in the environment for people to stay in, but you have active recruitment so you can continue to bring in the talent that you need, you\'ll just progressively fall behind,” he said.Zooming out, the panelists pointed to a dearth of information from the new administration regarding strategy and areas of focus.“It is tough to discern exactly where they\'re coming from,” Sasinowski said, citing mixed messages from the administration, such as “reestablishing the gold standard” and reducing regulations on stem cell clinics. “This is like the flat Earthers taking over NASA,” Woodcock said. In the analogy, she describes a group of people who feel that their beliefs and opinions have been ignored, and, once in power, fire anyone who disagrees with them.“It\'s really beyond the pale,” Woodcock said. “It is not science. And this is [a] science-based regulatory agency, which means legal science. And the messages they are getting are not about science.”“These purges, these proposed reorganizations—this is not about management or leadership,” the former FDA official continued. “There are hundreds of articles in Harvard Business Review about how to manage an organization—this wouldn\'t be in the top 10.”“This might be in one of the top 10 [ways] of how not to run a business or an organization,” she added.“Maybe the flat Earthers want that destruction because they\'re angry. Okay, they\'ve been left out—nobody honored their views,” Woodcock said. “So, I think we have to be … we really have to look that in the face and understand that is actually what\'s happening.”Fierce Biotech has reached out to the HHS for comment and will update this article if more information becomes available.

疫苗高管变更

2022-08-17

President Joe Biden yesterday afternoon signed into law historic, decades-in-the-making new drug pricing reforms as part of a wider reconciliation bill that will likely take a chunk out of biopharma companies’ profits for some blockbusters just prior to generic or biosimilar competition.

The partisan bill (

all Democrats

in the House and Senate voted for it, and all Republicans voted against it) includes not only Medicare price negotiations — which won’t kick off until 2026, leaving ample time for a

legal challenge

— but mandatory inflation-related rebates, and a $2,000 annual cap on what seniors’ pay for their prescription drugs.

On the positive side: the White House said 1.4 million Medicare beneficiaries will benefit from the $2,000 cap on out-of-pocket costs, while another 3.3 million Medicare enrollees will benefit from a separate $35 monthly cap on their insulin, though a wider rollout of that cap to the commercial insulin market failed to pass.

“I got here as a 29-year-old kid. We were promising to make sure that Medicare would have the power to negotiate lower drug prices back then,” Biden said during the signing ceremony yesterday. “But guess what? We’re giving Medicare the power to negotiate those prices now, on some drugs. This means seniors are going to pay less for their prescription drugs while we’re changing circumstances for people on Medicare by putting a cap — a cap of a maximum of $2,000 a year on their prescription drug costs, no matter what the reason for those prescriptions are.”

Beginning in 2026, price concessions will kick off for 10 of the most expensive single-source drugs in Medicare’s Part D program, building up to 20 Part D drugs and 20 Part B drugs in 2029 and beyond, with prices generally capped by at least 40%.

But only drugs that have been marketed for 9 years, or biologics marketed for 13 years, can be included in the negotiations, meaning companies will have almost a decade to reap the rewards of their blockbusters (and it’s hard to imagine anything less than a blockbuster will be included in negotiations).

Beginning October 1, 2023, pharma companies that will be hit with the negotiations in 2026 will have to sign an agreement on the negotiations, and then in Feb. 2024, CMS will propose a maximum fair price for those first 10 drugs, according to

new slides

from the law firm Hyman, Phelps, & McNamara.

But CMS will have to consider multiple factors in determining these new prices and provide a rationale, including the cost of R&D, patents and exclusivity, whether a drug addresses an unmet need, and others. CMS also must renegotiate the prices if a drug moves from being marketed for less than 12 years to more than 12, or less than 16 years to more than 16.

And renegotiations may (or may not) occur if a new indication is approved, but without that assurance, many in the biopharma industry have raised concerns that there will be less incentive to invest in the type of research to add new indications. The days of megablockbusters racking up new indications and extending their monopolies, as seen with AbbVie’s Humira or Amgen’s Enbrel, may now be a thing of the past.

The bill includes a number of heavy sticks to mandate participation, including $1 million per day in fines for failing to provide the info requested by CMS, and $100 million per piece of false info provided.

But considerable attention by Congress has also been paid to smaller biopharma companies, with varying levels of negotiations for drugs and biologics with the impending competition. Biosimilar manufacturers can request a one-year delay in negotiations for any reference biologics, and if a biosimilar app has already been submitted, CMS can delay the selection of a biologic.

Meanwhile, the bill also establishes new quarterly rebates on single-source Part B and D drugs and biologics that see their prices rise faster than the rate of inflation. The first mandatory Part D rebate period begins in October and runs through the end of the fiscal year, but drugs on FDA’s shortage list may be waived from the rebates, or have them lowered. Failing to pay these new rebates means companies will have to pay 125% of what the rebates would’ve cost.

Democrats had sought to extend these rebates to the private market too, but the Senate parliamentarian ruled against their inclusion, which limits the size of the rebates. However, commercial prices do still factor into the calculations for the Medicare inflationary rebates, according to

Harvard’s Benjamin Rome

, so it’s not as if companies will be able to increase all of their prices across the board to make up for the losses from any price spikes impacted by the new Medicare inflation-related rebates.

Several Republican members of Congress during the House floor debate last week over this bill tried to signal that this linkage of rebates to inflation would mean that drug prices would rise faster than normal. But even with the self-imposed 9.9% cap on drug price increases that pharma companies have followed for years now, these new rebates should slow drug price increases even further.

This is the multi-billion dollar question that neither the Congressional Budget Office nor the biopharma industry did a very good job of explaining.

On the one hand, some pharma companies will take a hit from both the inflation-rebate provisions and the negotiations, but on the other hand, the companies will find ways to recoup those losses, either via higher launch prices, potentially low-volume generic/biosimilar entry deals, or other creative ways.

The true impact on biopharma R&D remains unknown, will likely remain unknown in the near future, and may be the type of statistic that’s difficult to track but both sides will use to claim victory on the law’s successes or failures.

For its part, the CBO has said that over the next 30 years, of the approximately 1,3000 drugs approved, about 15 drugs may be cut from biopharma companies’ collective pipelines, including 2 over the 2023-2032 period, about 5 over the subsequent decade, and about 8 over the third decade.

But the CBO also projects that the inflation-rebate and negotiation provisions mentioned above would increase the launch prices for drugs that are not yet on the market relative to what such prices would be otherwise, which may offset some of those losses that would cut into their R&D budgets.

Under the inflation-rebate provisions, CBO also says “manufacturers would have an incentive to launch new drugs at a higher price to offset slower growth in prices over time.”

But Big Pharma trying to either game or sue over this law shouldn’t come as a surprise, Washington University law professor Rachel Sachs writes at

Health Affairs

.

And for the generic drug industry, which opposed the Inflation Reduction Act as much as their Big Pharma peers, CBO said it did not analyze the effects of the negotiations on the introduction of new generic drugs. The generic industry has lamented the fact that it may invest in generic drugs for reference products that will be hit with the negotiation provisions, thereby lessening the industry’s ability to go after lucrative targets.

仿制药生物类似药

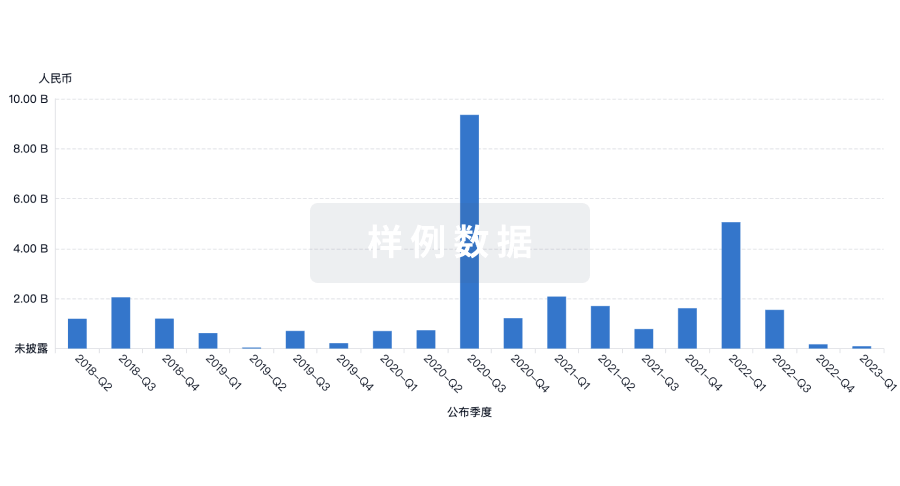

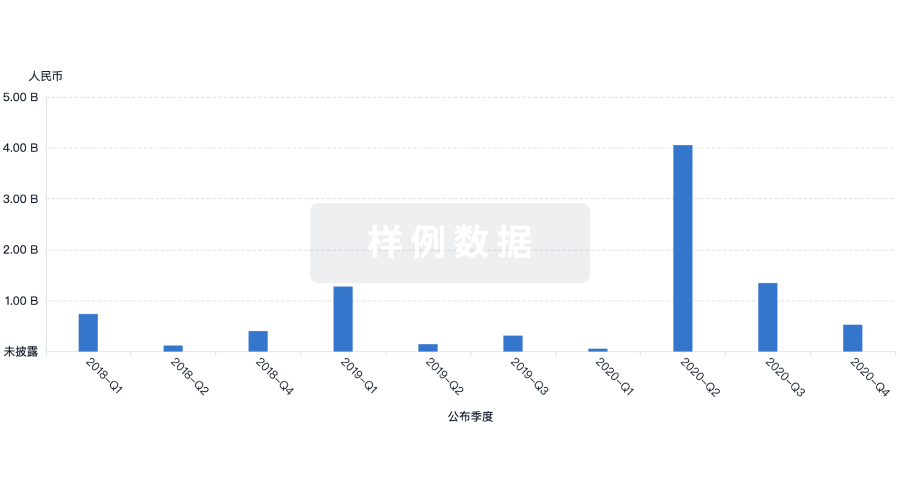

100 项与 Hyman, Phelps & McNamara PC 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 Hyman, Phelps & McNamara PC 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

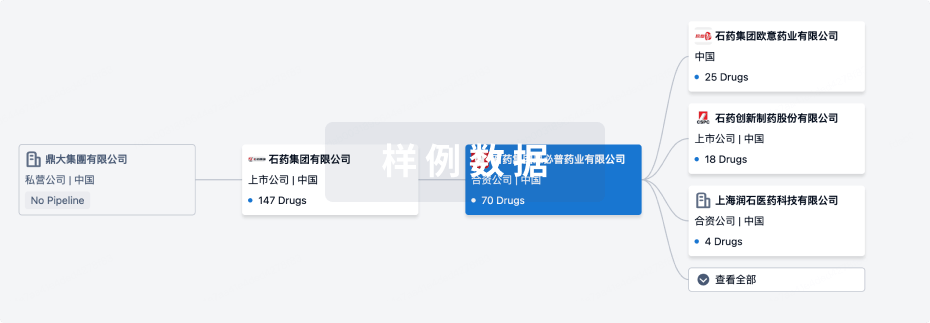

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2025年11月03日管线快照

无数据报导

登录后保持更新

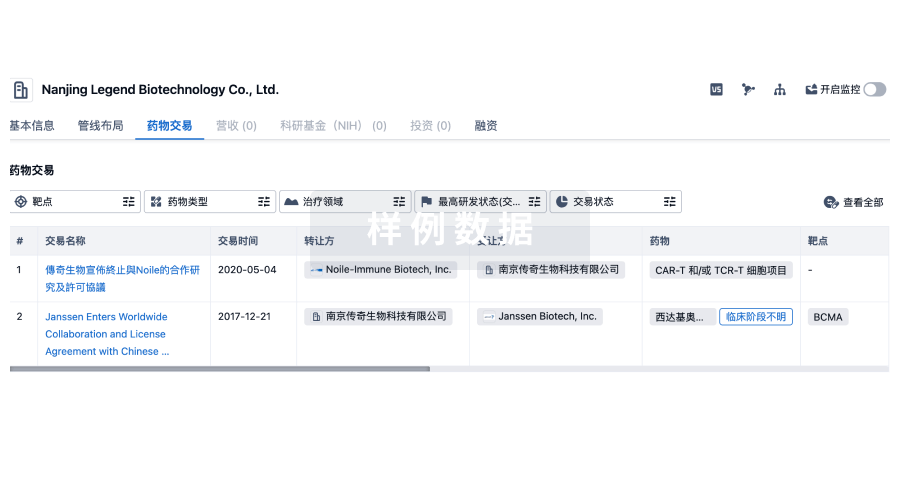

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

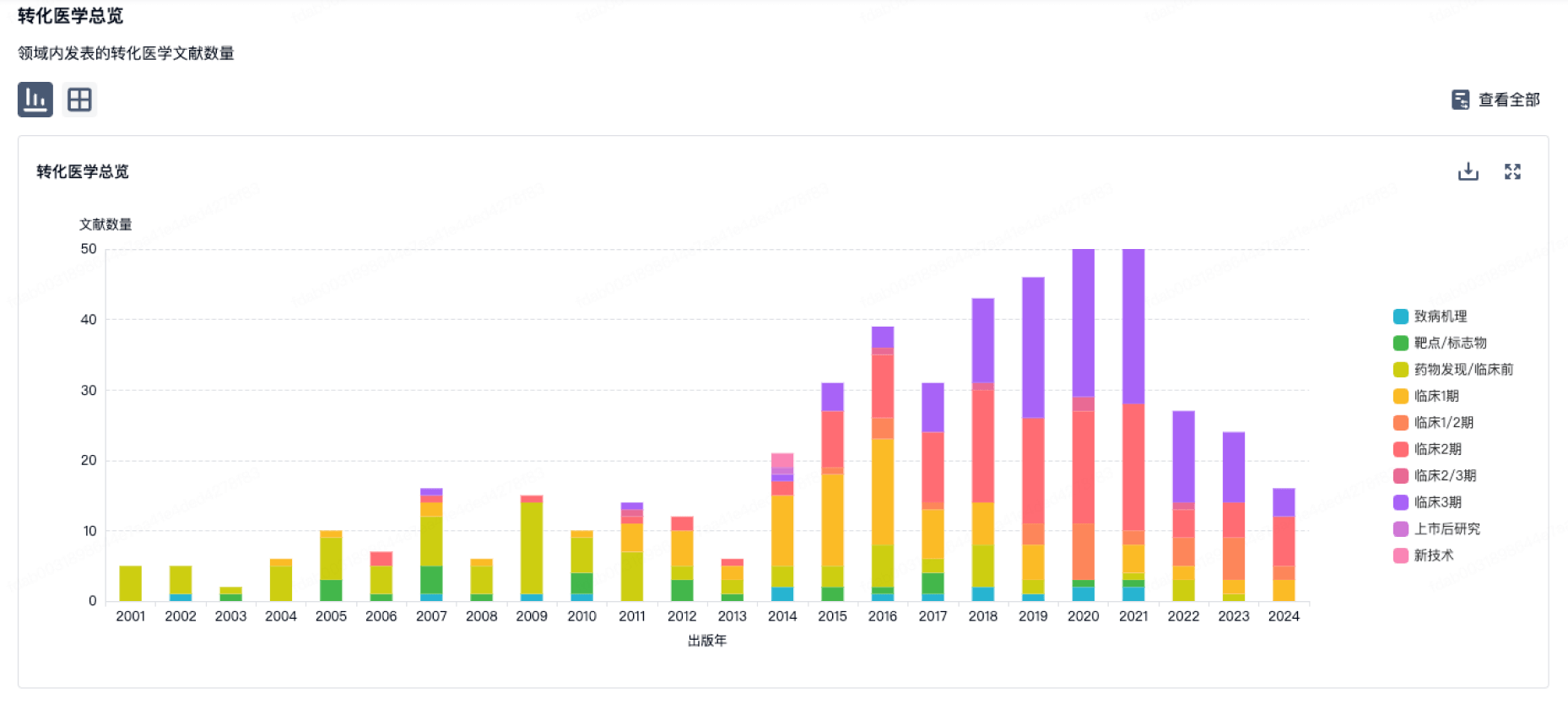

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

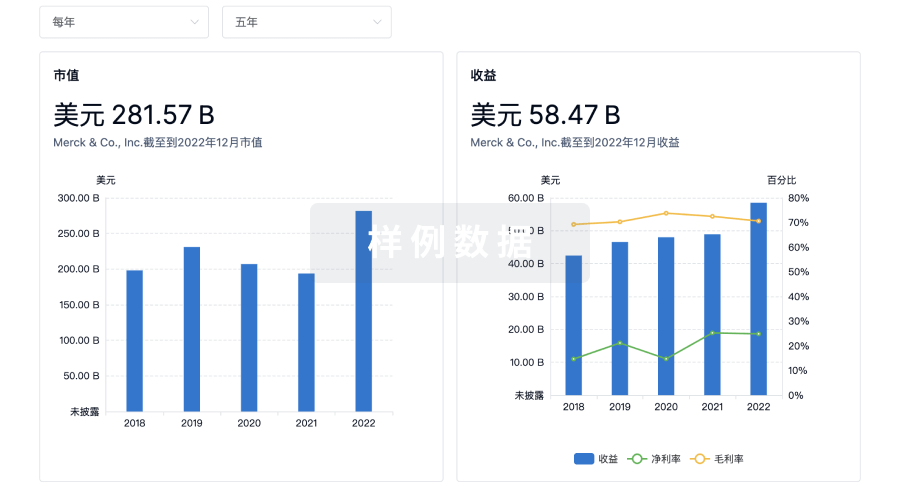

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用