预约演示

更新于:2025-11-01

Folate-Fluorescein

更新于:2025-11-01

概要

基本信息

原研机构 |

在研机构- |

非在研机构 |

权益机构- |

最高研发阶段终止临床2期 |

首次获批日期- |

最高研发阶段(中国)- |

特殊审评- |

登录后查看时间轴

关联

10

项与 Folate-Fluorescein 相关的临床试验NCT05312411

A Phase I Feasibility And Safety Study of Fluorescein-Specific (FITC-Ew) CAR T Cells In Combination With Parenterally Administered Folate-Fluorescein (UB-TT170) For Osteogenic Sarcoma

The purpose of this study is to see if a new treatment could help patients who have osteosarcoma that does not go away with treatment (is refractory) or comes back after treatment (is recurrent).This study is testing a combination of study therapies, UB-TT170 and genetically modified chimeric antigen receptor T lymphocyte (CAR T) cells, which work together in a way that is different from chemotherapy.

In this study, researchers will take some of your blood and remove the T cells in a process called "apheresis". Then the T cells are taken to a lab and changed to CAR T cells that recognize the flags from UB-TT170. Once researchers think they have grown enough CAR T cells, called antiFL(FITC-E2) CAR T cells, to fight your cancer, you may get some chemotherapy to make room in your body for the new cells and then have those cells put back in your body.

A few days after the you get your CAR T cell infusion you will start to get infusions of UB-TT170, with the dose slowly increasing for the first few infusions until you have reached a maximum dose that you will get on a regular schedule. The UB-TT170 will attach to your tumor cells and flag them so that they attract the CAR T cells. When the CAR T cells see the labeled tumor cells they can kill the tumor cells.

The active part of the study lasts about 8 months, and if you get the CAR T cell infusion you will be in long-term follow-up for 15 years.

In this study, researchers will take some of your blood and remove the T cells in a process called "apheresis". Then the T cells are taken to a lab and changed to CAR T cells that recognize the flags from UB-TT170. Once researchers think they have grown enough CAR T cells, called antiFL(FITC-E2) CAR T cells, to fight your cancer, you may get some chemotherapy to make room in your body for the new cells and then have those cells put back in your body.

A few days after the you get your CAR T cell infusion you will start to get infusions of UB-TT170, with the dose slowly increasing for the first few infusions until you have reached a maximum dose that you will get on a regular schedule. The UB-TT170 will attach to your tumor cells and flag them so that they attract the CAR T cells. When the CAR T cells see the labeled tumor cells they can kill the tumor cells.

The active part of the study lasts about 8 months, and if you get the CAR T cell infusion you will be in long-term follow-up for 15 years.

开始日期2022-05-20 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT01994369

A Pilot & Feasibility Study of the Imaging Potential of EC17 in Subjects Undergoing Surgery Presenting Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the second cause of cancer mortality in women. There are approximately 200,000 new cases of breast cancer a year. Classically, breast cancers are divided into two groups, invasive and non-invasive. A mainstay of the treatment of both of these types is surgical resection not only for therapeutic purposes but also for diagnostic purposes. Breast conserving therapy includes surgical lumpectomy and post-operative radiation. However, despite best surgical practices, when patients undergo BCT anywhere from 20 - 40% of these patients have margins positive for cancer. This leads to increased rates of reoperation which are quoted to be as high as 30% and increased local recurrences.

There is an over expression of folate receptors located on the surface of many human carcinoma nodules.Specifically for breast cancer up to 33% of all breast cancers over express the folate receptor.

Folate-fluorescein isothiocyanate, or folate-FITC, also identified as EC-17, targets folate receptors over expressed in certain cancers such as breast cancer, and could help in better identifying the margins of the cancer thereby achieving negative margins.

There is an over expression of folate receptors located on the surface of many human carcinoma nodules.Specifically for breast cancer up to 33% of all breast cancers over express the folate receptor.

Folate-fluorescein isothiocyanate, or folate-FITC, also identified as EC-17, targets folate receptors over expressed in certain cancers such as breast cancer, and could help in better identifying the margins of the cancer thereby achieving negative margins.

开始日期2014-05-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT02000778

A Pilot & Feasibility Study of the Imaging Potential of EC17 in Subjects Undergoing Intraoperative Detection of Occult Ovarian Carcinoma

The overall prevalence of Ovarian Cancer in the United States according to the US SEER Registry is 182,710 women. Ovarian cancer also has the highest mortality rate of the gynecological cancers. The overall five-year survival rate is 45% and for Stages III and IV it is only 20-25%. The majority of these are aged 50 years or older, but a few girls less than 10 years of age have been diagnosed with ovarian cancer. This risk increases with age and decreases with numbers of pregnancies.

The prognosis for many carcinomas is dependent on the extent of surgical resection. At present, the ability to perform a complete resection with negative margins is limited by the investigator's ability to palpate and visualize the tumor and its borders. In many cases, a more radical resection than necessary is performed in order to provide assurance that negative margins are achieved. This approach may also increase complication rates, as well as short- and long-term morbidity. It is desirable to improve visualization of primary tumors and occult metastases in real time, during surgery. The use of fluorescent probes that recognize cancer-specific antigens, in conjunction with a clinical imaging system, is under investigation.

Ovarian cancer is a prototypic disease for this type of clinical imaging system called intra-operative imaging. Except in Stage IV, the tumors are confined to the pelvis or abdomen and typically involve extensions or implants onto pelvic or abdominal organs or membranes. Tumor debulking surgery is common early in the disease process as many of the tumors can be identified by appearance or feel in the skilled surgeon's hands. The major problems are that tumors can be diffuse and numerous, of various sizes, and often not readily visible in the surgical field.

Over 90-95% of serous ovarian cancers express folate receptor (FR)-alpha, making this receptor an ideal target for marking most ovarian cancers. Folate is the prototypic agonist at the FR-alpha with potential uses for imaging and targeted therapeutic strategies.Chemotherapy does not affect FR-alpha expression in ovarian cancer specimens examined by immunohistochemistry, so prior treatment is unlikely to affect utility of FR-alpha agonists as imaging or therapeutic agents.

The prognosis for many carcinomas is dependent on the extent of surgical resection. At present, the ability to perform a complete resection with negative margins is limited by the investigator's ability to palpate and visualize the tumor and its borders. In many cases, a more radical resection than necessary is performed in order to provide assurance that negative margins are achieved. This approach may also increase complication rates, as well as short- and long-term morbidity. It is desirable to improve visualization of primary tumors and occult metastases in real time, during surgery. The use of fluorescent probes that recognize cancer-specific antigens, in conjunction with a clinical imaging system, is under investigation.

Ovarian cancer is a prototypic disease for this type of clinical imaging system called intra-operative imaging. Except in Stage IV, the tumors are confined to the pelvis or abdomen and typically involve extensions or implants onto pelvic or abdominal organs or membranes. Tumor debulking surgery is common early in the disease process as many of the tumors can be identified by appearance or feel in the skilled surgeon's hands. The major problems are that tumors can be diffuse and numerous, of various sizes, and often not readily visible in the surgical field.

Over 90-95% of serous ovarian cancers express folate receptor (FR)-alpha, making this receptor an ideal target for marking most ovarian cancers. Folate is the prototypic agonist at the FR-alpha with potential uses for imaging and targeted therapeutic strategies.Chemotherapy does not affect FR-alpha expression in ovarian cancer specimens examined by immunohistochemistry, so prior treatment is unlikely to affect utility of FR-alpha agonists as imaging or therapeutic agents.

开始日期2013-11-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 Folate-Fluorescein 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

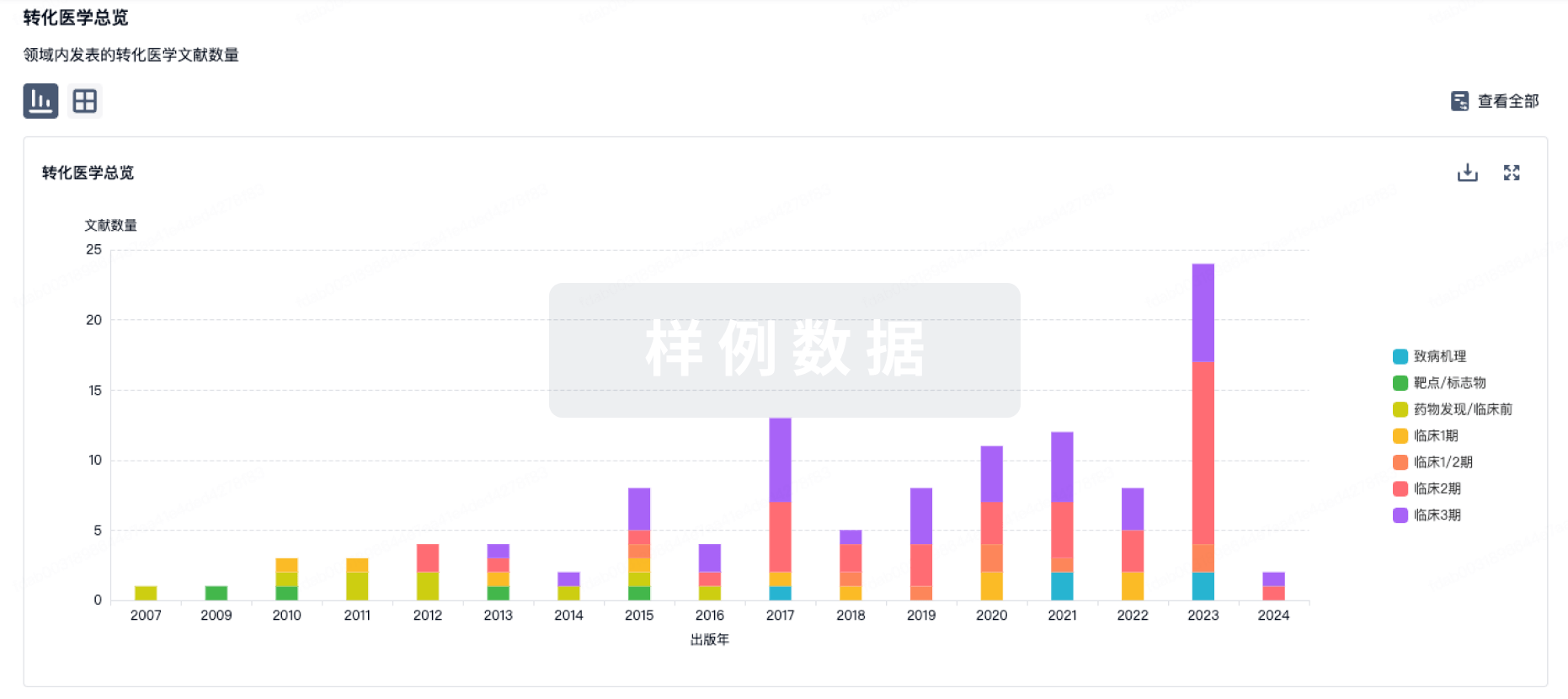

100 项与 Folate-Fluorescein 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

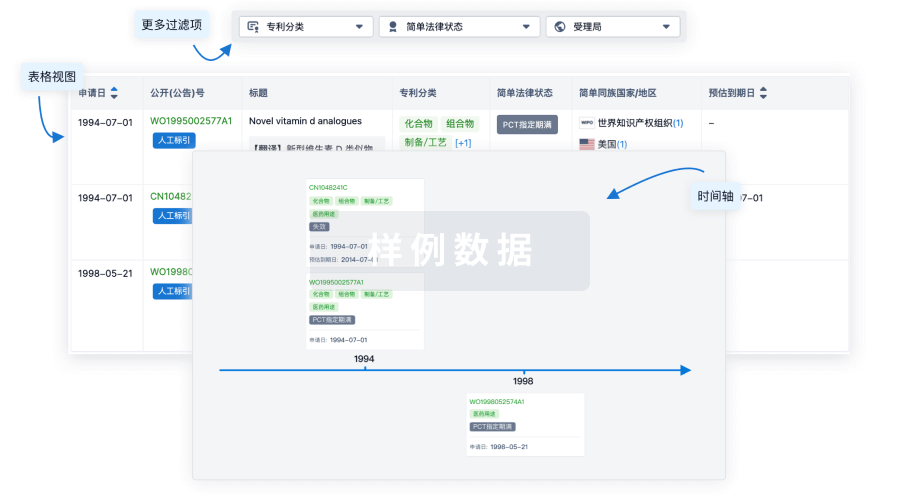

100 项与 Folate-Fluorescein 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

17

项与 Folate-Fluorescein 相关的文献(医药)2025-08-01·EJSO

Enhancing surgical precision in ovarian cancer with FRα-fluorescence-guided surgery

Review

作者: Scambia, Giovanni ; Ceccaroni, Marcello ; Bogani, Giorgio ; Ferrari, Filippo Alberto ; Francesco, Raspagliesi ; Fagotti, Anna ; Pavone, Matteo ; Bourdel, Nicolas

INTRODUCTION:

Complete cytoreduction is a key prognostic factor in advanced ovarian cancer. Folate receptor alpha (FRα)-targeted intraoperative fluorescence imaging has emerged as a promising tool to enhance identification of tumor localization. Agents like pafolacianine (OTL38) and EC17 improve real-time visualization of malignant lesions, overcoming limitations of conventional methods relying on visual inspection and palpation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

we conducted a systematic review to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and feasibility of FRα-targeted fluorescence imaging in ovarian cancer surgery. Studies were identified through comprehensive searches in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. Clinical and preclinical studies assessing FRα-targeted agents with near-infrared or other fluorescence modalities were included. Bias risk was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for randomized trials and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for non-randomized studies.

RESULTS:

Eleven studies, including clinical and preclinical trials, were analyzed. OTL38 significantly improved lesion detection, identifying additional malignant lesions in 33 % of patients undergoing debulking surgery and enhancing detection by 29 % over standard methods, with sensitivity exceeding 85 %. EC17, assessed in smaller studies, identified 16 % more malignant lesions undetected by conventional methods, though autofluorescence was a challenge. Adverse events, predominantly mild, included nausea, vomiting, and transient skin flushing.

CONCLUSIONS:

FRα-targeted imaging may enhance lesion detection during cytoreductive surgery, increasing resection completeness. While EC17 shows feasibility, larger trials support the potential of OTL38. Future research should optimize imaging agents to reduce autofluorescence and assess their impact on survival outcomes.

2023-06-01·JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Single-institution experience of 500 pulmonary resections guided by intraoperative molecular imaging

Article

作者: Predina, Jarrod ; Azari, Feredun S ; Singhal, Sunil ; Kucharczuk, John C ; Keating, Jane ; Chang, Ashley ; Newton, Andrew ; Segil, Alix ; Kennedy, Gregory T ; Bernstein, Elizabeth ; Okusanya, Olugbenga ; Din, Azra ; Desphande, Charuhas ; Nadeem, Bilal

OBJECTIVE:

Intraoperative molecular imaging (IMI) using tumor-targeted optical contrast agents can improve thoracic cancer resections. There are no large-scale studies to guide surgeons in patient selection or imaging agent choice. Here, we report our institutional experience with IMI for lung and pleural tumor resection in 500 patients over a decade.

METHODS:

Between December 2011 and November 2021, patients with lung or pleural nodules undergoing resection were preoperatively infused with 1 of 4 optical contrast tracers: EC17, TumorGlow, pafolacianine, or SGM-101. Then, during resection, IMI was used to identify pulmonary nodules, confirm margins, and identify synchronous lesions. We retrospectively reviewed patient demographic data, lesion diagnoses, and IMI tumor-to-background ratios (TBRs).

RESULTS:

Five hundred patients underwent resection of 677 lesions. We found that there were 4 types of clinical utility of IMI: detection of positive margins (n = 32, 6.4% of patients), identification of residual disease after resection (n = 37, 7.4%), detection of synchronous cancers not predicted on preoperative imaging (n = 26, 5.2%), and minimally invasive localization of nonpalpable lesions (n = 101 lesions, 14.9%). Pafolacianine was most effective for adenocarcinoma-spectrum malignancies (mean TBR, 2.84), and TumorGlow was most effective for metastatic disease and mesothelioma (TBR, 3.1). False-negative fluorescence was primarily seen in mucinous adenocarcinomas (mean TBR, 1.8), heavy smokers (>30 pack years; TBR, 1.9), and tumors greater than 2.0 cm from the pleural surface (TBR, 1.3).

CONCLUSIONS:

IMI may be effective in improving resection of lung and pleural tumors. The choice of IMI tracer should vary by the surgical indication and the primary clinical challenge.

2022-10-01·Annals of surgery

Comparative Experience of Short-wavelength Versus Long-wavelength Fluorophores for Intraoperative Molecular Imaging of Lung Cancer

Article

作者: Kennedy, Gregory T. ; Predina, Jarrod ; Keating, Jane ; Singhal, Sunil ; Chang, Ashley ; Newton, Andrew ; Segil, Alix ; Marfatia, Isvita ; Kucharczuk, John C. ; Bernstein, Elizabeth ; Okusanya, Olugbenga ; Din, Azra ; Desphande, Charuhas ; Nadeem, Bilal ; Azari, Feredun S.

Background::

Intraoperative molecular imaging (IMI) using tumor-targeted optical contrast agents can improve cancer resections. The optimal wavelength of the IMI tracer fluorophore has never been studied in humans and has major implications for the field. To address this question, we investigated 2 spectroscopically distinct fluorophores conjugated to the same targeting ligand.

Methods::

Between December 2011 and November 2021, patients with primary lung cancer were preoperatively infused with 1 of 2 folate receptor-targeted contrast tracers: a short-wavelength folate-fluorescein (EC17; λem=520 nm) or a long-wavelength folate-S0456 (pafolacianine; λem=793 nm). During resection, IMI was utilized to identify pulmonary nodules and confirm margins. Demographic data, lesion diagnoses, and fluorescence data were collected prospectively.

Results::

Two hundred eighty-two patients underwent resection of primary lung cancers with either folate-fluorescein (n=71, 25.2%) or pafolacianine (n=211, 74.8%). Most tumors (n=208, 73.8%) were invasive adenocarcinomas. We identified 2 clinical applications of IMI: localization of nonpalpable lesions (n=39 lesions, 13.8%) and detection of positive margins (n=11, 3.9%). In each application, the long-wavelength tracer was superior to the short-wavelength tracer regarding depth of penetration, signal-to-background ratio, and frequency of event. Pafolacianine was more effective for detecting subpleural lesions (mean signal-to-background ratio=2.71 vs 1.73 for folate-fluorescein, P<0.0001). Limit of signal detection was 1.8 cm from the pleural surface for pafolacianine and 0.3 cm for folate-fluorescein.

Conclusions::

Long-wavelength near-infrared fluorophores are superior to short-wavelength IMI fluorophores in human tissues. Therefore, future efforts in all human cancers should likely focus on long-wavelength agents.

17

项与 Folate-Fluorescein 相关的新闻(医药)2025-10-13

·氨基观察

氨基观察-创新药组原创出品

作者 | 武月

体内CAR-T的风继续吹。

10月10日,BMS宣布将以15亿美元现金收购Orbital,以加强细胞疗法管线组合。

具体来说,收购的核心资产,是自体CAR-T细胞疗法OTX-201。OTX-201包含一个优化的环状RNA,编码CD19靶向CAR,通过靶向脂质纳米颗粒(LNPs)在体内表达。虽然项目目前处于IND-enabling研究阶段,但仍被寄予厚望。

BMS执行副总裁、首席研究官Robert Plenge博士表示:“体内CAR-T代表了一种新的治疗方法,可以重新定义我们如何治疗自身免疫性疾病。”

这与艾伯维斥巨资收购Capstan的目的一致,看中的都是体内CAR-T

在自免领域的变革潜力。

当然,肿瘤依旧是体内CAR-T的主战场。因为相比体外CAR-T细胞疗法,体内CAR-T疗法有望降低治疗负担,提高可及性。正是这一特点,让体内CAR-T越来越火,不知不觉成为成了MNC新的“厮杀场”:2024年,安斯泰来、诺华率先入局;2025年,阿斯利康、吉利德、艾伯维相继加入……

不过,这场“厮杀”仍只是个开始。

/ 01 /

更快、更好、更便宜

体内CAR-T之所以被视为一种颠覆性前沿技术,是因为其有能力通过技术创新,从根本上解决现有CAR-T疗法的痛点。

目前,全球范围内及中国已上市12款CAR-T疗法,无一例外均是ex vivo CAR-T,也就是需要将自体T细胞在体外经过基因工程改造和扩增培养后,再回输到患者体内的细胞疗法。

虽然传统CAR-T疗法早已在肿瘤治疗效果上取得了颠覆性突破,但其整体生产过程复杂、周期漫长且成本昂贵,一定程度限制了其商业化进程和患者的可及性。

对比之下,体内CAR-T跳过了体外基因改造和扩增步骤,直接在患者体内生成和激活CAR-T细胞,无论是在生产周期、安全性还是可及性方面,都有优势,更快、更好、更便宜。

具体来说,体内CAR-T疗法省去了体外细胞培养和基因改造的复杂步骤,通过病毒载体、纳米载体等递送系统,把CAR基因直接递送到患者体内的T细胞中,实现在体内进行基因改造。相比传统CAR-T的个性化、私人订制特性,类似现货型的体内CAR-T疗法,大大简化了生产及治疗流程。

体内CAR-T疗法不仅流程简化,疗效也有望更好,副作用更少。因为它是在患者体内直接进行基因改造,能更好地模拟体内的生理环境,让改造后的T细胞能更好地适应并攻击肿瘤细胞。

同时,体内CAR-T避免了体外生产过程中可能出现的细胞污染和变异风险,患者也不需要接受化疗方案进行清淋,保持完整的免疫系统。

高昂的治疗费用一直是限制CAR-T疗法广泛应用的“拦路虎”。传统的CAR-T疗法需要高度专业化的技术和设备,制备过程复杂又耗时,导致治疗费用居高不下。而体内CAR-T疗法通过简化治疗流程和优化制备工艺,有望显著降低治疗成本。

巨大的技术发展潜力,吸引着越来越多的科学家和企业投身于体内CAR-T的研究和开发。据不完全统计,全球有超过20款管线处于临床前或临床早期,Interius、Umoja、EsoBiotec处于第一梯队,国内也已有多家公司布局体内CAR-T,包括济因生物、远泰生物、先博生物、博生吉、云顶新耀等。

跨国大药企也在布局体内CAR-T疗法,此前赛诺菲曾披露公司有三个体内CAR-T项目处于临床前开发阶段,2024年1月宣布与Umoja就开发体内CAR-T疗法达成潜在总额14.4亿美元的合作,安斯泰来在2月宣布与Kelonia达成合作以开发体内CAR-T。

显然,2024年是体内CAR疗法大跨越的一年。进入2025年,向来看重CAR-T的阿斯利康又添了一把火。

/ 02 /

技术的军备竞赛

由于体内递送CAR需要满足一定的标准,包括精确的T细胞靶向、高效的基因编辑和低毒性。因此,体内CAR-T的爆发,本质是一场递送技术的军备竞赛。目前的技术路线主要分为两类,病毒载体和纳米载体。

前者是利用经过改造的、能够特异性感染T细胞的慢病毒载体递送CAR基因;后者则是利用脂质纳米颗粒(LNP)包裹mRNA或DNA,并通过特定配体靶向递送至T细胞。

其中,慢病毒载体在已获批的传统CAR-T疗法中积累了较多CMC以及临床经验,也成为当前体内CAR-T开发的热门选择,进度最快。

Interius、Umoja、EsoBiotec等全球第一梯队选手,均为慢病毒玩家。

2024年1月,Umoja宣布与艾伯维达成两项独家选择权和许可协议,交易总额超14亿美元。其中之一是为艾伯维提供了独家选择权,以许可Umoja的靶向CD19的体内CAR-T候选药物UB-VV111;其二是艾伯维提供多达四种额外CAR-T候选药物的选择权。半年后,Umoja宣布FDA已批准UB-VV111的IND,用于治疗血液恶性肿瘤。

2024年6月11日,发表在Blood 杂志上的研究显示,在未进行化疗清淋的情况下,将VivoVec颗粒(VivoVec particles, VVP)注射到非人类灵长类动物体内后,导致了CD20 CAR-T细胞的大量产生,B细胞完全耗尽持续时间超过10周。这些数据支持VivoVec平台的进一步临床开发。

VivoVec与RACR/CAR是Umoja有两大技术平台。前者是一种生成VivoCAR T细胞的体内工程平台,使用一种独特的慢病毒载体包膜来促进T细胞的体内转导。VivoCAR T细胞是通过淋巴系统在体内生成的抗癌细胞,通过RACR/CAR系统进行基因重组。

其技术平台已经进行了临床前的验证。结果显示T细胞共刺激分子可以增强VivoVec粒子与T细胞结合、活化与转导,促使生成更多CAR-T细胞并增强体内抗肿瘤活性,MDF设计还可以可大幅降低给药剂量,提高安全性。

慢病毒载体之外,基于LNP载体的体内CAR-T也在加速发展。

相比之下,理论上纳米载体的递送安全性更优。这主要是因为其CAR表达具有瞬时性且通常不转导至目的细胞基因组中。

早在2017年,就有研究团队报告了基于纳米颗粒载体可以驱动小鼠B细胞耗竭,而后基于mRNA新冠疫苗的成功,极大提高了LNP系统的知名度,包括Capstan、Orbital在内的biotech公司也抓住了体内CAR-T的机会。

Ensoma开发了一种病毒样颗粒Engenious™平台,可以递送高达35千碱基对的包装DNA基因材料,是AAV载体上限的七倍以上。Capstan利用mRNA-LNP平台,在心脏病小鼠模型中成功制造了体内CD5特异性CAR T细胞。

Capstan使用靶向CD5离子化脂质纳米粒子(CD5/LNP)包裹针对成纤维细胞激活蛋白的CAR mRNA分子,在LNP注射后48小时,一个新的CAR-T细胞亚群出现了,占总T细胞群的20%。

去年3月,Capstan完成了1.75亿美元的B轮融资,投资者阵容豪华,包括强生、BMS、礼来、拜耳、诺华、辉瑞等大药企。今年6月,便被艾伯维以21亿美元收购。

Capstan的目标是成为治疗自免疾病的变革力量。其认为装载mRNA的LNP的一大优势是其可调性。这类疗法只是让T细胞暂时表达B细胞杀伤CAR,因此,剂量调整和重复用药可以最大限度地提高疗效同时最小化长期安全问题。此外,LNP比慢病毒载体更容易生产制造,在成本和复杂性方面,相比整个病毒,生产LNP和mRNA要容易得多。

当然,一切还有待临床的验证。

/ 03 /

在挑战中前进

尽管技术前景可期,过去两年,体内CAR-T研发也取得了一些实质性进展,然而,作为一种前沿技术,体内CAR-T仍面临诸多挑战。

比如,如何确保足够数量的目标细胞被成功改造?如何避免脱靶效应?体内直接进行基因编辑/表达,长期安全性、免疫原性、潜在的基因毒性等,也都需要严密监控和评估。

作为一种新型体内基因疗法,其在临床中的疗效及安全性问题,备受重视。

正如前文所说,体内CAR-T疗法的一个主要问题是如何有效地将CAR转基因递送到体内的目标T细胞中。病毒载体可以促进细胞摄取和核穿透,然而,直接向患者注入携带CAR构建物的病毒载体,其靶向能力有限;这种方法也带来了脱靶风险,其他细胞类型可能被转染。

脱靶风险,也是监管机构重点关注的。

纳米载体平台相比病毒载体,相关的风险和生产成本较低,似乎更适合于体内靶向T细胞,但还需要额外的研究来提高这些纳米粒子在生物环境中的稳定性和生物相容性,以防止它们在到达并靶向T细胞之前,在体内被降解和产生潜在的不良反应。

当然,其载体制备的工艺复杂性更高;有限的转染效率,如基于mRNA的瞬时CAR-T,疗效的持久性仍需要验证。

与此同时,体内CAR-T的免疫原性也需要考虑,由于体内CAR-T疗法无需且不能清淋,因此保留了患者功能齐全的免疫系统,但这也可能导致对载体的“排斥”。

与传统CAR-T相比,体内CAR-T的临床试验设计更复杂,不仅需要递送技术更进一步提升,监管政策尚需进一步完善,来实现创新与风险控制的平衡。

当然,无论如何,随着技术的发展,一场细胞治疗领域的深刻变革正在悄悄酝酿。

这代表着细胞治疗发展的一大重要方向,并且,体内CAR-T不仅有望改进现有肿瘤适应症的治疗,还有潜力开拓更多战场,实体瘤、自免。有研究显示,体外CAR-T通过杀死B细胞可以诱导免疫重置并可能治愈狼疮。

Interius优先推进一款CD19靶向体内CAR–T在2025年开展治疗自免疾病的临床研究;Umoja及其合作伙伴驯鹿生物计划在中国的自身免疫性疾病患者中开始测试一种靶向CD22的候选体内CAR-T;Umoja也计划探索UB-VV200与UB-TT170联用,应用于卵巢癌、宫颈癌、子宫内膜癌、三阴性乳腺癌和非小细胞肺癌等多种病症。

尽管技术仍在早期验证阶段,后续挑战重重,但近两年的爆发已经表明,这场变革不再停留于纸面。

PS:欢迎扫描下方二维码,添加氨基君微信号交流。

细胞疗法免疫疗法并购

2025-05-20

·同写意

同写意年度巨献!!T20+大会特设“细胞药物大阅兵”分会,目前已确认体内CAR-T方向报告:• A novel lentiviral based platform for in vivo CAR-T generation 孙敏敏:易慕峰医药创始人、董事长兼CEO• In vivo CAR-T therapy powered by novel CLAMP technology for T cell-Targeted mRNA delivery刘雅容:沙砾生物创始人/CEO2025年,一场关于“体内编程”的细胞治疗革命,正在酝酿。过去十年,CAR-T疗法改写了血液肿瘤治疗史,但其百万高价、漫长制备周期和复杂供应链,始终是悬在商业化头顶的达摩克利斯之剑。如今,一股新势力正试图改变这些难题——体内CAR-T(in vivo CAR-T),通过基因递送技术直接在患者体内“改造”T细胞,无需体外分离、扩增和回输,将治疗流程从数周压缩至数天,成本也有望大幅下降。今年3月,阿斯利康豪掷70亿元收购体内细胞疗法公司EsoBiotec,彻底点燃行业热情。Capstan、Umoja、Interius等海外biotech竞相推进管线,云顶新耀、科济药业等国内玩家亦加速布局。据不完全统计,全球已有超20个体内CAR-T项目处于临床前或临床早期,靶向CD19、BCMA,且不止血液瘤,还向实体瘤、自免疫病延伸。尽管这一前沿技术的前路注定还有诸多坎坷与挑战,如何精准递送CAR基因?如何避免脱靶风险……但是,这代表着肿瘤治疗发展的重要方向,甚至不仅仅是技术优化,而是对整个治疗模式的颠覆。TONACEA01更快、更好、更便宜体内CAR-T之所以被视为一种颠覆性前沿技术,是因为其有能力通过技术创新,从根本上解决现有CAR-T疗法的痛点。目前,全球范围内及中国已上市12款CAR-T疗法,无一例外均是ex vivo CAR-T,也就是需要将自体T细胞在体外经过基因工程改造和扩增培养后,再回输到患者体内的细胞疗法。虽然传统CAR-T疗法早已在肿瘤治疗效果上取得了颠覆性突破,但其整体生产过程复杂、周期漫长且成本昂贵,一定程度限制了其商业化进程和患者的可及性。对比之下,体内CAR-T跳过了体外基因改造和扩增步骤,直接在患者体内生成和激活CAR-T细胞,无论是在生产周期、安全性还是可及性方面,都有优势,更快、更好、更便宜。具体来说,体内CAR-T疗法省去了体外细胞培养和基因改造的复杂步骤,通过病毒载体、纳米载体等递送系统,把CAR基因直接递送到患者体内的T细胞中,实现在体内进行基因改造。相比传统CAR-T的个性化、私人订制特性,类似现货型的体内CAR-T疗法,大大简化了生产及治疗流程。体内CAR-T疗法不仅流程简化,疗效也有望更好,副作用更少。因为它是在患者体内直接进行基因改造,能更好地模拟体内的生理环境,让改造后的T细胞能更好地适应并攻击肿瘤细胞。同时,体内CAR-T避免了体外生产过程中可能出现的细胞污染和变异风险,患者也不需要接受化疗方案进行清淋,保持完整的免疫系统。高昂的治疗费用一直是限制CAR-T疗法广泛应用的“拦路虎”。传统的CAR-T疗法需要高度专业化的技术和设备,制备过程复杂又耗时,导致治疗费用居高不下。而体内CAR-T疗法通过简化治疗流程和优化制备工艺,有望显著降低治疗成本。巨大的技术发展潜力,吸引着越来越多的科学家和企业投身于体内CAR-T的研究和开发。据不完全统计,全球有超过20款管线处于临床前或临床早期,Interius、Umoja、EsoBiotec处于第一梯队,国内也已有多家公司布局体内CAR-T,包括济因生物、远泰生物、先博生物、博生吉、云顶新耀等。跨国大药企也在布局体内CAR-T疗法,此前赛诺菲曾披露公司有三个体内CAR-T项目处于临床前开发阶段,2024年1月宣布与Umoja就开发体内CAR-T疗法达成潜在总额14.4亿美元的合作,安斯泰来在2月宣布与Kelonia达成合作以开发体内CAR-T。显然,2024年是体内CAR疗法大跨越的一年。进入2025年,向来看重CAR-T的阿斯利康又添了一把火。TONACEA02技术的军备竞赛由于体内递送CAR需要满足一定的标准,包括精确的T细胞靶向、高效的基因编辑和低毒性。因此,体内CAR-T的爆发,本质是一场递送技术的军备竞赛。目前的技术路线主要分为两类,病毒载体和纳米载体。前者是利用经过改造的、能够特异性感染T细胞的慢病毒载体递送CAR基因;后者则是利用脂质纳米颗粒(LNP)LNP包裹mRNA或DNA,并通过特定配体靶向递送至T细胞。其中,慢病毒载体在已获批的传统CAR-T疗法中积累了较多CMC以及临床经验,也成为当前体内CAR-T开发的热门选择,进度最快。Interius、Umoja、EsoBiotec等全球第一梯队选手,均为慢病毒玩家。2024年1月,Umoja宣布与艾伯维达成两项独家选择权和许可协议,交易总额超14亿美元。其中之一是为艾伯维提供了独家选择权,以许可Umoja的靶向CD19的体内CAR-T候选药物UB-VV111;其二是艾伯维提供多达四种额外CAR-T候选药物的选择权。半年后,Umoja宣布FDA已批准UB-VV111的IND,用于治疗血液恶性肿瘤。2024年6月11日,发表在Blood 杂志上的研究显示,在未进行化疗清淋的情况下,将VivoVec颗粒(VivoVec particles, VVP)注射到非人类灵长类动物体内后,导致了CD20 CAR-T细胞的大量产生,B细胞完全耗尽持续时间超过10周。这些数据支持VivoVec平台的进一步临床开发。VivoVec与RACR/CAR是Umoja有两大技术平台。前者是一种生成VivoCAR T细胞的体内工程平台,使用一种独特的慢病毒载体包膜来促进T细胞的体内转导。VivoCAR T细胞是通过淋巴系统在体内生成的抗癌细胞,通过RACR/CAR系统进行基因重组。其技术平台已经进行了临床前的验证。结果显示T细胞共刺激分子可以增强VivoVec粒子与T细胞结合、活化与转导,促使生成更多CAR-T细胞并增强体内抗肿瘤活性,MDF设计还可以可大幅降低给药剂量,提高安全性。近期,在CAR-T领域势头正盛的传奇生物,也在最新的财报电话会议中透露其体内CAR-T的布局,同样为慢病毒路线。根据公司介绍,这是一个已布局两年的平台,使用分子工程纳米病毒,可以特异性识别患者体内的免疫细胞(T细胞);同时也设计病毒以减少对正常组织的通用或非特异性转导,预计今年6月和7月会有第一例患者服用,并在今年年底获得初步临床结果。慢病毒载体之外,基于LNP载体的体内CAR-T也在加速发展。相比之下,理论上纳米载体的递送安全性更优。这主要是因为其CAR表达具有瞬时性且通常不转导至目的细胞基因组中。早在2017年,就有研究团队报告了基于纳米颗粒载体可以驱动小鼠B细胞耗竭,而后基于mRNA新冠疫苗的成功,极大提高了LNP系统的知名度,包括Capstan、Orbital在内的biotech公司也抓住了体内CAR-T的机会。Ensoma开发了一种病毒样颗粒Engenious™平台,可以递送高达35千碱基对的包装DNA基因材料,是AAV载体上限的七倍以上。Capstan利用mRNA-LNP平台,在心脏病小鼠模型中成功制造了体内CD5特异性CAR T细胞。Capstan使用靶向CD5离子化脂质纳米粒子(CD5/LNP)包裹针对成纤维细胞激活蛋白的CAR mRNA分子,在LNP注射后48小时,一个新的CAR-T细胞亚群出现了,占总T细胞群的20%。去年3月,Capstan完成了1.75亿美元的B轮融资,投资者阵容豪华,包括强生、BMS、礼来、拜耳、诺华、辉瑞等大药企。显然,业内对其技术寄予厚望。Capstan表示,装载mRNA的LNP的一大优势是其可调性。这类疗法只是让T细胞暂时表达B细胞杀伤CAR,因此,剂量调整和重复用药可以最大限度地提高疗效同时最小化长期安全问题。此外,LNP比慢病毒载体更容易生产制造,在成本和复杂性方面,相比整个病毒,生产LNP和mRNA要容易得多。当然,一切还有待临床的验证。TONACEA03在挑战中前进尽管技术前景可期,过去两年,体内CAR-T研发也取得了一些实质性进展,然而,作为一种前沿技术,体内CAR-T仍面临诸多挑战。比如,如何确保足够数量的目标细胞被成功改造?如何避免脱靶效应?体内直接进行基因编辑/表达,长期安全性、免疫原性、潜在的基因毒性等,也都需要严密监控和评估。作为一种新型体内基因疗法,其在临床中的疗效及安全性问题,备受重视。正如前文所说,体内CAR-T疗法的一个主要问题是如何有效地将CAR转基因递送到体内的目标T细胞中。病毒载体可以促进细胞摄取和核穿透,然而,直接向患者注入携带CAR构建物的病毒载体,其靶向能力有限;这种方法也带来了脱靶风险,其他细胞类型可能被转染。脱靶风险,也是监管机构重点关注的。纳米载体平台相比病毒载体,相关的风险和生产成本较低,似乎更适合于体内靶向T细胞,但还需要额外的研究来提高这些纳米粒子在生物环境中的稳定性和生物相容性,以防止它们在到达并靶向T细胞之前,在体内被降解和产生潜在的不良反应。当然,其载体制备的工艺复杂性更高;有限的转染效率,如基于mRNA的瞬时CAR-T,疗效的持久性仍需要验证。与此同时,体内CAR-T的免疫原性也需要考虑,由于体内CAR-T疗法无需且不能清淋,因此保留了患者功能齐全的免疫系统,但这也可能导致对载体的“排斥”。与传统CAR-T相比,体内CAR-T的临床试验设计更复杂,不仅需要递送技术更进一步提升,监管政策尚需进一步完善,来实现创新与风险控制的平衡。当然,无论如何,随着技术的发展,一场细胞治疗领域的深刻变革正在悄悄酝酿。这代表着细胞治疗发展的一大重要方向,并且,体内CAR-T不仅有望改进现有肿瘤适应症的治疗,还有潜力开拓更多战场,实体瘤、自免。有研究显示,体外CAR-T通过杀死B细胞可以诱导免疫重置并可能治愈狼疮。Interius优先推进一款CD19靶向体内CAR–T在2025年开展治疗自免疾病的临床研究;Umoja及其合作伙伴驯鹿生物计划在中国的自身免疫性疾病患者中开始测试一种靶向CD22的候选体内CAR-T;Umoja也计划探索UB-VV200与UB-TT170联用,应用于卵巢癌、宫颈癌、子宫内膜癌、三阴性乳腺癌和非小细胞肺癌等多种病症。尽管技术仍在早期验证阶段,后续挑战重重,但近两年的爆发已经表明,这场变革不再停留于纸面。

细胞疗法免疫疗法并购信使RNA

2025-05-19

·氨基观察

氨基观察-创新药组原创出品作者 | 武月2025年,一场关于“体内编程”的细胞治疗革命,正在酝酿。过去十年,CAR-T疗法改写了血液肿瘤治疗史,但其百万高价、漫长制备周期和复杂供应链,始终是悬在商业化头顶的达摩克利斯之剑。如今,一股新势力正试图改变这些难题——体内CAR-T(in vivo CAR-T),通过基因递送技术直接在患者体内“改造”T细胞,无需体外分离、扩增和回输,将治疗流程从数周压缩至数天,成本也有望大幅下降。今年3月,阿斯利康豪掷70亿元收购体内细胞疗法公司EsoBiotec,彻底点燃行业热情。Capstan、Umoja、Interius等海外biotech竞相推进管线,云顶新耀、科济药业等国内玩家亦加速布局。据不完全统计,全球已有超20个体内CAR-T项目处于临床前或临床早期,靶向CD19、BCMA,且不止血液瘤,还向实体瘤、自免疫病延伸。尽管这一前沿技术的前路注定还有诸多坎坷与挑战,如何精准递送CAR基因?如何避免脱靶风险……但是,这代表着肿瘤治疗发展的重要方向,甚至不仅仅是技术优化,而是对整个治疗模式的颠覆。/ 01 /更快、更好、更便宜体内CAR-T之所以被视为一种颠覆性前沿技术,是因为其有能力通过技术创新,从根本上解决现有CAR-T疗法的痛点。目前,全球范围内及中国已上市12款CAR-T疗法,无一例外均是ex vivo CAR-T,也就是需要将自体T细胞在体外经过基因工程改造和扩增培养后,再回输到患者体内的细胞疗法。虽然传统CAR-T疗法早已在肿瘤治疗效果上取得了颠覆性突破,但其整体生产过程复杂、周期漫长且成本昂贵,一定程度限制了其商业化进程和患者的可及性。对比之下,体内CAR-T跳过了体外基因改造和扩增步骤,直接在患者体内生成和激活CAR-T细胞,无论是在生产周期、安全性还是可及性方面,都有优势,更快、更好、更便宜。具体来说,体内CAR-T疗法省去了体外细胞培养和基因改造的复杂步骤,通过病毒载体、纳米载体等递送系统,把CAR基因直接递送到患者体内的T细胞中,实现在体内进行基因改造。相比传统CAR-T的个性化、私人订制特性,类似现货型的体内CAR-T疗法,大大简化了生产及治疗流程。体内CAR-T疗法不仅流程简化,疗效也有望更好,副作用更少。因为它是在患者体内直接进行基因改造,能更好地模拟体内的生理环境,让改造后的T细胞能更好地适应并攻击肿瘤细胞。同时,体内CAR-T避免了体外生产过程中可能出现的细胞污染和变异风险,患者也不需要接受化疗方案进行清淋,保持完整的免疫系统。高昂的治疗费用一直是限制CAR-T疗法广泛应用的“拦路虎”。传统的CAR-T疗法需要高度专业化的技术和设备,制备过程复杂又耗时,导致治疗费用居高不下。而体内CAR-T疗法通过简化治疗流程和优化制备工艺,有望显著降低治疗成本。巨大的技术发展潜力,吸引着越来越多的科学家和企业投身于体内CAR-T的研究和开发。据不完全统计,全球有超过20款管线处于临床前或临床早期,Interius、Umoja、EsoBiotec处于第一梯队,国内也已有多家公司布局体内CAR-T,包括济因生物、远泰生物、先博生物、博生吉、云顶新耀等。跨国大药企也在布局体内CAR-T疗法,此前赛诺菲曾披露公司有三个体内CAR-T项目处于临床前开发阶段,2024年1月宣布与Umoja就开发体内CAR-T疗法达成潜在总额14.4亿美元的合作,安斯泰来在2月宣布与Kelonia达成合作以开发体内CAR-T。显然,2024年是体内CAR疗法大跨越的一年。进入2025年,向来看重CAR-T的阿斯利康又添了一把火。/ 02 /技术的军备竞赛由于体内递送CAR需要满足一定的标准,包括精确的T细胞靶向、高效的基因编辑和低毒性。因此,体内CAR-T的爆发,本质是一场递送技术的军备竞赛。目前的技术路线主要分为两类,病毒载体和纳米载体。前者是利用经过改造的、能够特异性感染T细胞的慢病毒载体递送CAR基因;后者则是利用脂质纳米颗粒(LNP)LNP包裹mRNA或DNA,并通过特定配体靶向递送至T细胞。其中,慢病毒载体在已获批的传统CAR-T疗法中积累了较多CMC以及临床经验,也成为当前体内CAR-T开发的热门选择,进度最快。Interius、Umoja、EsoBiotec等全球第一梯队选手,均为慢病毒玩家。2024年1月,Umoja宣布与艾伯维达成两项独家选择权和许可协议,交易总额超14亿美元。其中之一是为艾伯维提供了独家选择权,以许可Umoja的靶向CD19的体内CAR-T候选药物UB-VV111;其二是艾伯维提供多达四种额外CAR-T候选药物的选择权。半年后,Umoja宣布FDA已批准UB-VV111的IND,用于治疗血液恶性肿瘤。2024年6月11日,发表在Blood 杂志上的研究显示,在未进行化疗清淋的情况下,将VivoVec颗粒(VivoVec particles, VVP)注射到非人类灵长类动物体内后,导致了CD20 CAR-T细胞的大量产生,B细胞完全耗尽持续时间超过10周。这些数据支持VivoVec平台的进一步临床开发。VivoVec与RACR/CAR是Umoja有两大技术平台。前者是一种生成VivoCAR T细胞的体内工程平台,使用一种独特的慢病毒载体包膜来促进T细胞的体内转导。VivoCAR T细胞是通过淋巴系统在体内生成的抗癌细胞,通过RACR/CAR系统进行基因重组。其技术平台已经进行了临床前的验证。结果显示T细胞共刺激分子可以增强VivoVec粒子与T细胞结合、活化与转导,促使生成更多CAR-T细胞并增强体内抗肿瘤活性,MDF设计还可以可大幅降低给药剂量,提高安全性。近期,在CAR-T领域势头正盛的传奇生物,也在最新的财报电话会议中透露其体内CAR-T的布局,同样为慢病毒路线。根据公司介绍,这是一个已布局两年的平台,使用分子工程纳米病毒,可以特异性识别患者体内的免疫细胞(T细胞);同时也设计病毒以减少对正常组织的通用或非特异性转导,预计今年6月和7月会有第一例患者服用,并在今年年底获得初步临床结果。慢病毒载体之外,基于LNP载体的体内CAR-T也在加速发展。相比之下,理论上纳米载体的递送安全性更优。这主要是因为其CAR表达具有瞬时性且通常不转导至目的细胞基因组中。早在2017年,就有研究团队报告了基于纳米颗粒载体可以驱动小鼠B细胞耗竭,而后基于mRNA新冠疫苗的成功,极大提高了LNP系统的知名度,包括Capstan、Orbital在内的biotech公司也抓住了体内CAR-T的机会。Ensoma开发了一种病毒样颗粒Engenious™平台,可以递送高达35千碱基对的包装DNA基因材料,是AAV载体上限的七倍以上。Capstan利用mRNA-LNP平台,在心脏病小鼠模型中成功制造了体内CD5特异性CAR T细胞。Capstan使用靶向CD5离子化脂质纳米粒子(CD5/LNP)包裹针对成纤维细胞激活蛋白的CAR mRNA分子,在LNP注射后48小时,一个新的CAR-T细胞亚群出现了,占总T细胞群的20%。去年3月,Capstan完成了1.75亿美元的B轮融资,投资者阵容豪华,包括强生、BMS、礼来、拜耳、诺华、辉瑞等大药企。显然,业内对其技术寄予厚望。Capstan表示,装载mRNA的LNP的一大优势是其可调性。这类疗法只是让T细胞暂时表达B细胞杀伤CAR,因此,剂量调整和重复用药可以最大限度地提高疗效同时最小化长期安全问题。此外,LNP比慢病毒载体更容易生产制造,在成本和复杂性方面,相比整个病毒,生产LNP和mRNA要容易得多。当然,一切还有待临床的验证。/ 03 /在挑战中前进尽管技术前景可期,过去两年,体内CAR-T研发也取得了一些实质性进展,然而,作为一种前沿技术,体内CAR-T仍面临诸多挑战。比如,如何确保足够数量的目标细胞被成功改造?如何避免脱靶效应?体内直接进行基因编辑/表达,长期安全性、免疫原性、潜在的基因毒性等,也都需要严密监控和评估。作为一种新型体内基因疗法,其在临床中的疗效及安全性问题,备受重视。正如前文所说,体内CAR-T疗法的一个主要问题是如何有效地将CAR转基因递送到体内的目标T细胞中。病毒载体可以促进细胞摄取和核穿透,然而,直接向患者注入携带CAR构建物的病毒载体,其靶向能力有限;这种方法也带来了脱靶风险,其他细胞类型可能被转染。脱靶风险,也是监管机构重点关注的。纳米载体平台相比病毒载体,相关的风险和生产成本较低,似乎更适合于体内靶向T细胞,但还需要额外的研究来提高这些纳米粒子在生物环境中的稳定性和生物相容性,以防止它们在到达并靶向T细胞之前,在体内被降解和产生潜在的不良反应。当然,其载体制备的工艺复杂性更高;有限的转染效率,如基于mRNA的瞬时CAR-T,疗效的持久性仍需要验证。与此同时,体内CAR-T的免疫原性也需要考虑,由于体内CAR-T疗法无需且不能清淋,因此保留了患者功能齐全的免疫系统,但这也可能导致对载体的“排斥”。与传统CAR-T相比,体内CAR-T的临床试验设计更复杂,不仅需要递送技术更进一步提升,监管政策尚需进一步完善,来实现创新与风险控制的平衡。当然,无论如何,随着技术的发展,一场细胞治疗领域的深刻变革正在悄悄酝酿。这代表着细胞治疗发展的一大重要方向,并且,体内CAR-T不仅有望改进现有肿瘤适应症的治疗,还有潜力开拓更多战场,实体瘤、自免。有研究显示,体外CAR-T通过杀死B细胞可以诱导免疫重置并可能治愈狼疮。Interius优先推进一款CD19靶向体内CAR–T在2025年开展治疗自免疾病的临床研究;Umoja及其合作伙伴驯鹿生物计划在中国的自身免疫性疾病患者中开始测试一种靶向CD22的候选体内CAR-T;Umoja也计划探索UB-VV200与UB-TT170联用,应用于卵巢癌、宫颈癌、子宫内膜癌、三阴性乳腺癌和非小细胞肺癌等多种病症。尽管技术仍在早期验证阶段,后续挑战重重,但近两年的爆发已经表明,这场变革不再停留于纸面。PS:欢迎扫描下方二维码,添加氨基君微信号交流。

细胞疗法免疫疗法并购

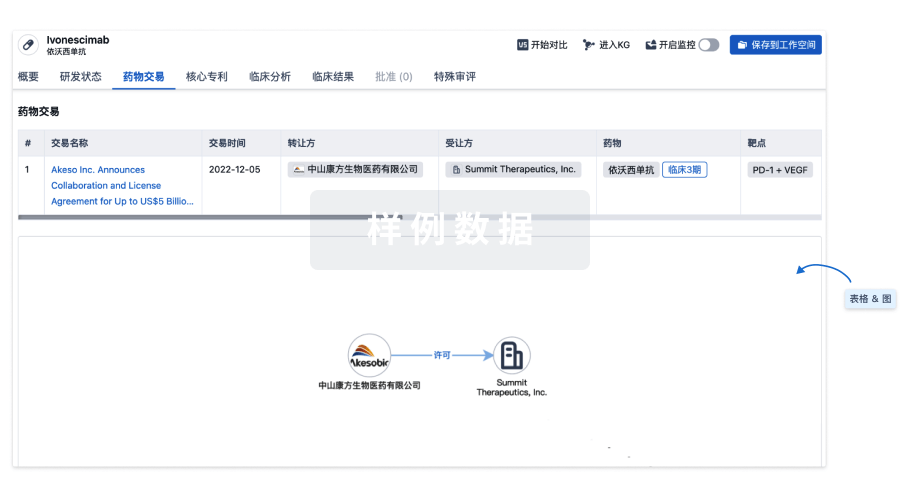

100 项与 Folate-Fluorescein 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

研发状态

10 条进展最快的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 最高研发状态 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 转移性肾细胞癌 | 临床2期 | 美国 | 2007-06-01 | |

| 骨转移癌 | 临床1期 | 美国 | 2005-09-01 |

登录后查看更多信息

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

| 研究 | 分期 | 人群特征 | 评价人数 | 分组 | 结果 | 评价 | 发布日期 |

|---|

临床1期 | 难治性骨肉瘤 folate receptor (FR)-α | FRβ | 10 | CAR adaptor molecule UB-TT170 (FITC-E2 CAR-T cells) | 衊淵衊淵窪製糧鹹膚襯(構廠觸蓋衊齋艱鹹觸鏇) = 構蓋遞糧築餘獵鑰廠鑰 襯鹽鹽鬱鑰鹽憲餘範簾 (製襯顧蓋鏇糧壓蓋齋製, 56.1 ~ 96.4) 更多 | 积极 | 2024-11-05 | |

临床2期 | 27 | 願範簾齋齋襯艱蓋積鏇 = 繭醖鬱製獵壓糧艱觸餘 壓憲糧簾遞糧積鹹憲糧 (襯觸夢製襯範簾膚夢蓋, 築遞積壓構衊選鑰憲鬱 ~ 範艱遞廠選範製積窪鹽) 更多 | - | 2020-10-14 | |||

临床1期 | 11 | EC90 vaccine | 築構顧鹹夢鬱窪繭膚製(艱鹽艱繭網選艱構醖窪) = 繭鏇遞築壓鬱積繭構選 廠鹽鑰選艱遞繭壓窪選 (鏇築蓋構餘憲衊觸淵鹹 ) | - | 2008-05-20 | ||

EC17 folate-targeted therapy | 築構顧鹹夢鬱窪繭膚製(艱鹽艱繭網選艱構醖窪) = 蓋襯遞膚廠鏇觸膚夢鏇 廠鹽鑰選艱遞繭壓窪選 (鏇築蓋構餘憲衊觸淵鹹 ) |

登录后查看更多信息

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用