预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

MASP2 Deficiency

MASP2缺陷

更新于:2025-05-07

基本信息

别名 LCAPD2、LECTIN COMPLEMENT ACTIVATION PATHWAY, DEFECT IN, 2、MASP2 DEFICIENCY + [2] |

简介- |

关联

1

项与 MASP2缺陷 相关的药物靶点 |

作用机制 MASP2抑制剂 |

在研机构 |

原研机构 |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床1期 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期1800-01-20 |

100 项与 MASP2缺陷 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 MASP2缺陷 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 MASP2缺陷 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

7

项与 MASP2缺陷 相关的文献(医药)2023-09-01·Journal of Neurochemistry

Upregulation of mesencephalic astrocyte‐derived neurotrophic factor (MANF ) expression offers protection against alcohol neurotoxicity

Article

作者: Zhang, Zuohui ; Li, Hui ; Wang, Yongchao ; Wen, Wen ; Hu, Di ; Luo, Jia ; Lin, Hong

2021-04-01·European Journal of Human Genetics2区 · 生物学

A human case of GIMAP6 deficiency: a novel primary immune deficiency

2区 · 生物学

Article

作者: Schejter, Yael Dinur ; Asherie, Nathalie ; Shadur, Bella ; Stepensky, Polina ; Kfir-Erenfeld, Shlomit ; Dubnikov, Taly ; NaserEddin, Adeeb ; Mor-Shaked, Hagar ; Elpeleg, Orly

2021-01-01·Neurobiology of Disease2区 · 医学

MANF is neuroprotective against ethanol-induced neurodegeneration through ameliorating ER stress

2区 · 医学

Article

作者: Li, Hui ; Xu, Hong ; Wen, Wen ; Wang, Yongchao ; Clementino, Marco ; Luo, Jia ; Xu, Mei ; Frank, Jacqueline ; Ma, Murong

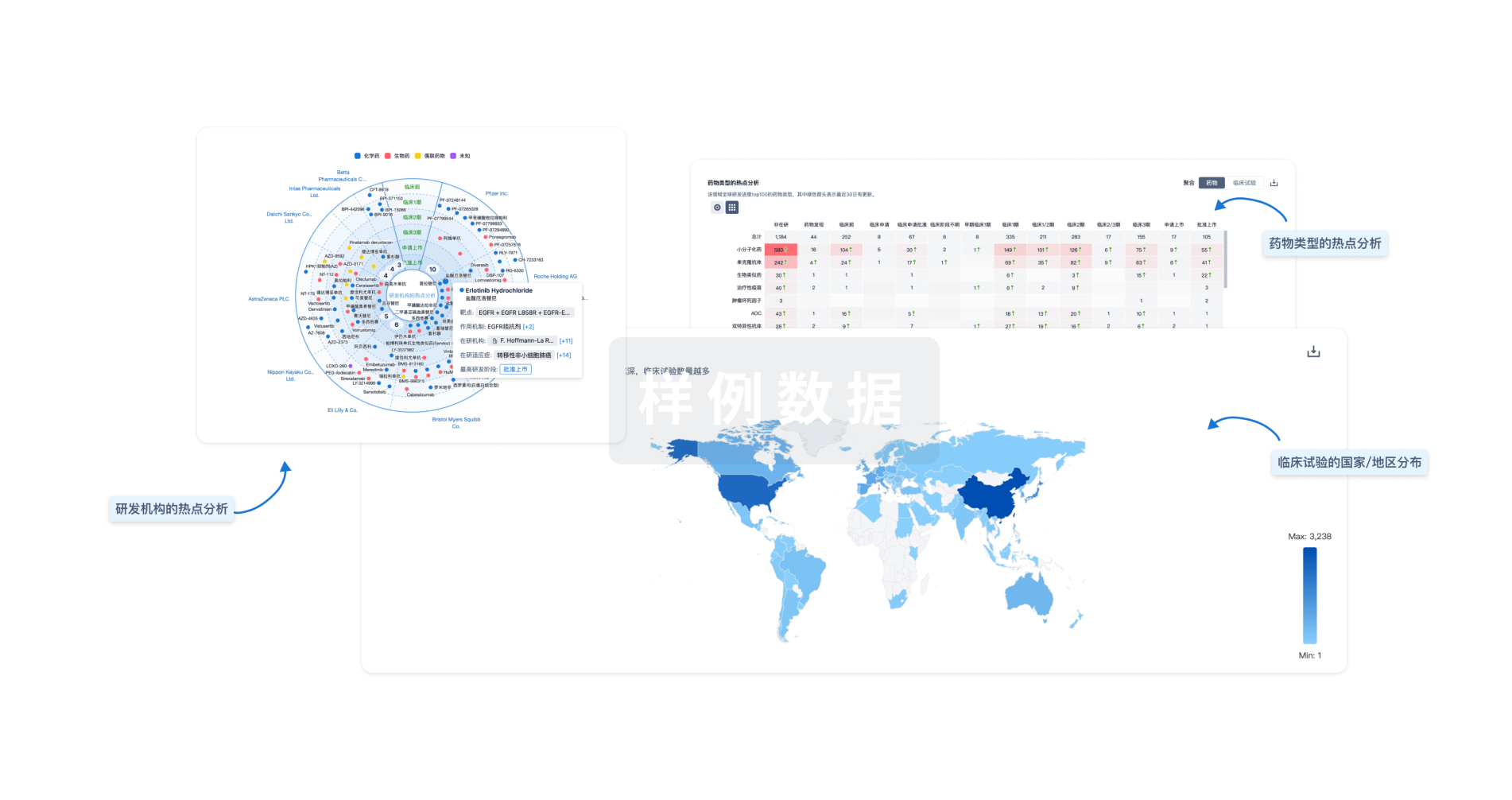

分析

对领域进行一次全面的分析。

登录

或

Eureka LS:

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用