预约演示

更新于:2025-01-23

Augusta State University

更新于:2025-01-23

概览

标签

肿瘤

治疗性疫苗

通用抗原疫苗

关联

1

项与 Augusta State University 相关的药物靶点- |

作用机制- |

在研机构 |

原研机构 |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

100 项与 Augusta State University 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 Augusta State University 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

159

项与 Augusta State University 相关的文献(医药)2022-01-01·Disability and health journal

Race/ethnic inequities in conjoint monitoring and screening for U.S. children 3 and under.

Article

作者: Heiman, Harry ; Barger, Brian ; Rice, Catherine ; Rizk, Sabrin ; Sanchez-Alvarez, Sonia ; Salmon, Ashley ; Benevides, Teal

2022-01-01·Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders3区 · 心理学

Are Developmental Monitoring and Screening Better Together for Early Autism Identification Across Race and Ethnic Groups?

3区 · 心理学

Article

作者: Sanchez-Alvarez, Sonia ; Barger, Brian ; Rice, Catherine ; Salmon, Ashley ; Crimmins, Daniel ; Benevides, Teal

2021-01-01·General Music Today

Using Picture Books as a Tool for Creating a Culturally Inclusive Elementary Music Classroom

作者: Hall, Suzanne

100 项与 Augusta State University 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 Augusta State University 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

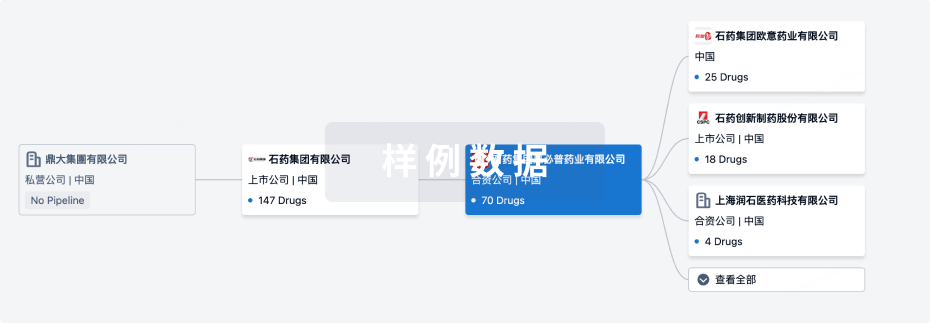

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2025年04月26日管线快照

管线布局中药物为当前组织机构及其子机构作为药物机构进行统计,早期临床1期并入临床1期,临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

临床前

1

登录后查看更多信息

当前项目

| 药物(靶点) | 适应症 | 全球最高研发状态 |

|---|---|---|

IDO peptide vaccine (IO Biotech) | 肿瘤 更多 | 临床前 |

登录后查看更多信息

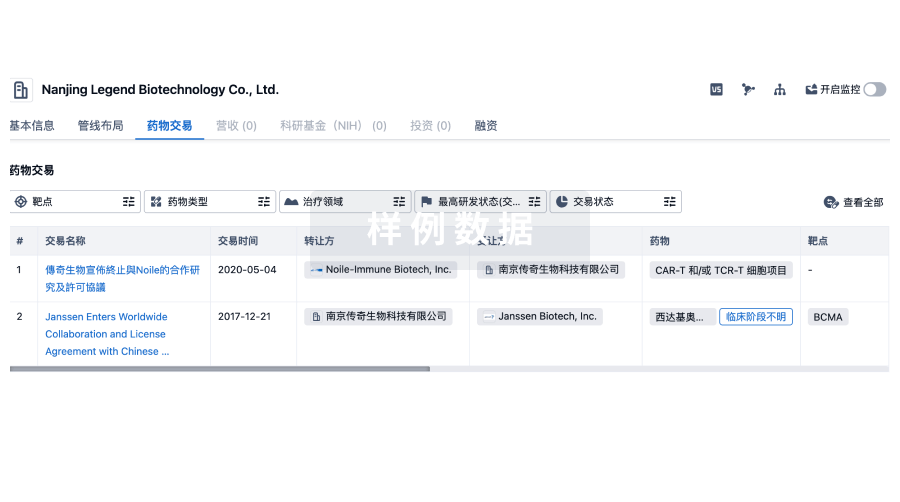

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

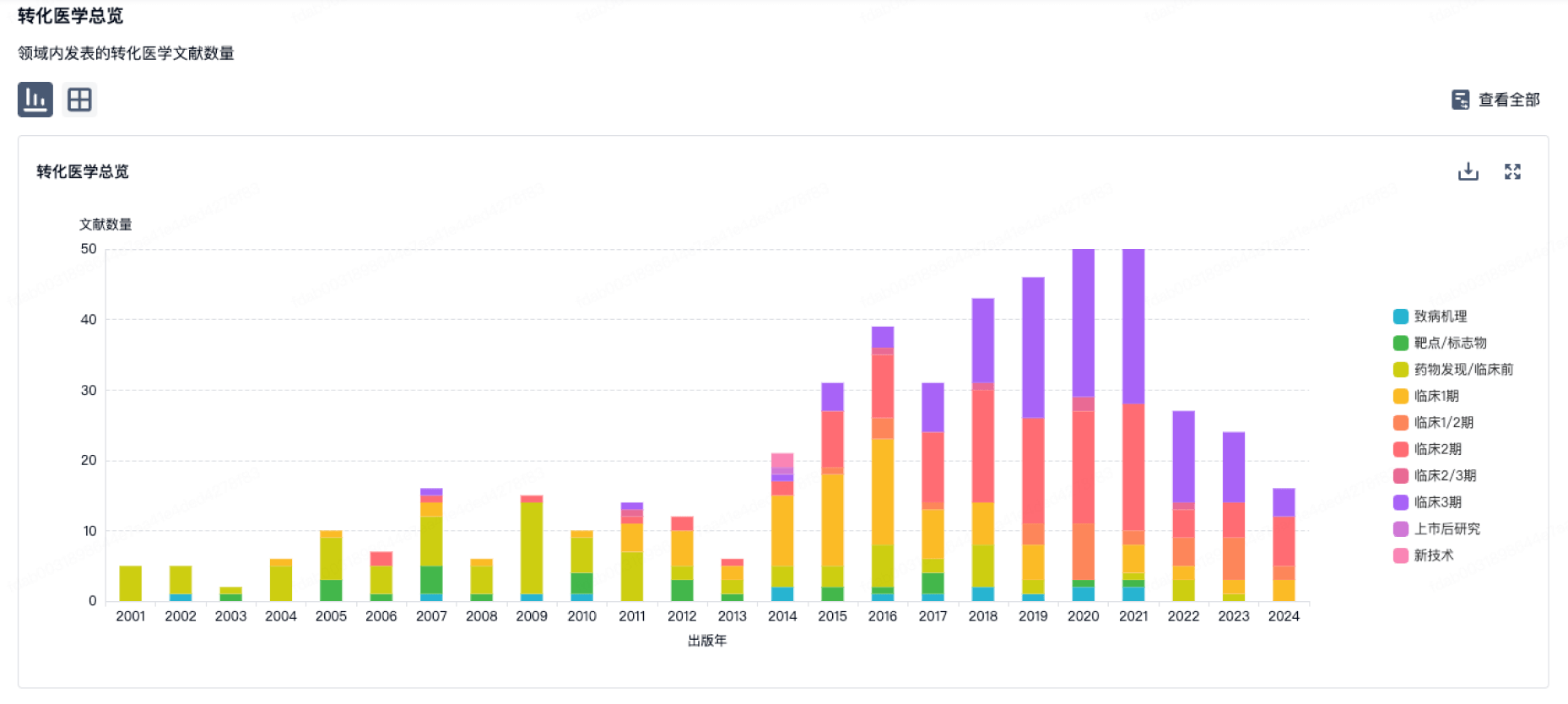

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

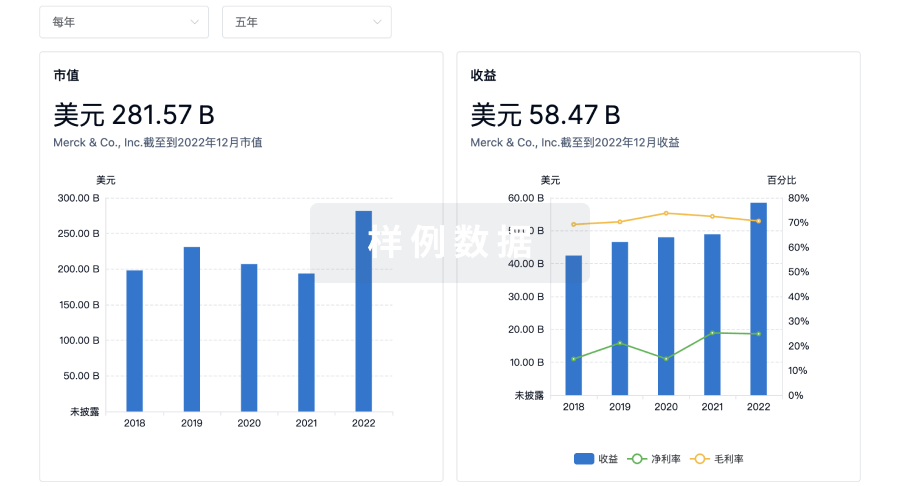

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

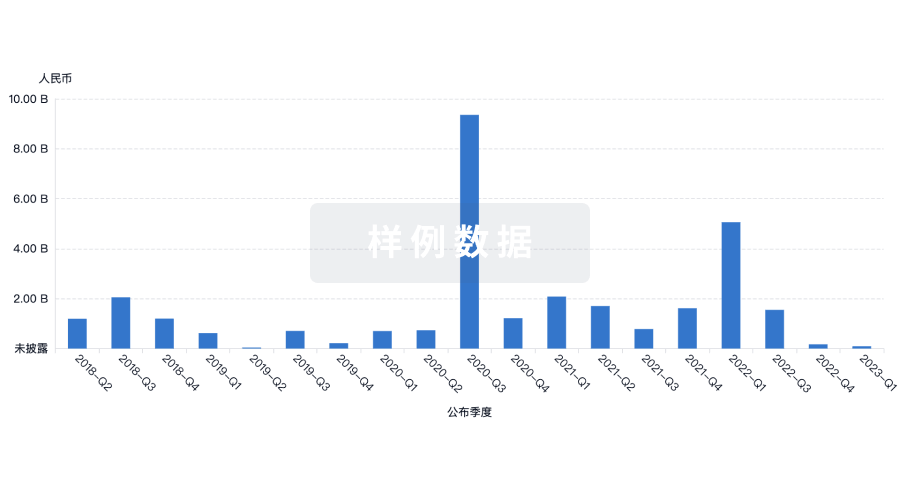

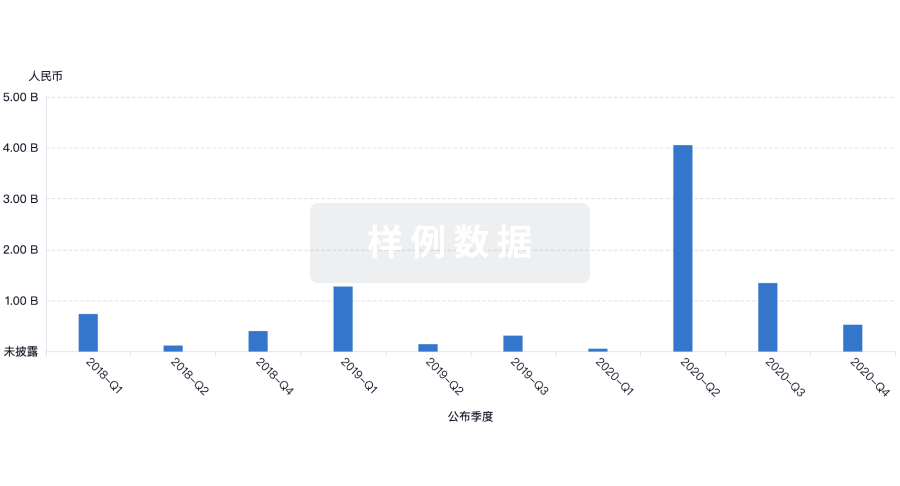

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

来和Eureka LS聊天吧

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用