预约演示

更新于:2025-08-29

The School of Pharmacy University of London

教育|United Kingdom

教育|United Kingdom

更新于:2025-08-29

概览

关联

100 项与 The School of Pharmacy University of London 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 The School of Pharmacy University of London 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

17

项与 The School of Pharmacy University of London 相关的文献(医药)2023-12-01·BMJ open quality

Validation of a method to assess the severity of medication administration errors in Brazil

Article

作者: Valli, Cleidenete Gomes ; de Souza, Luis Eugenio Portela Fernandes ; Machado, Juliana Ferreira Fernandes ; Pinto, Charleston Ribeiro ; Assunção-Costa, Lindemberg ; Franklin, Bryony Dean

Introduction:

Medication errors are frequent and have high economic and social impacts; however, some medication errors are more likely to result in harm than others. Therefore, it is critical to determine their severity. Various tools exist to measure and classify the harm associated with medication errors; although, few have been validated internationally.

Methods:

We validated an existing method for assessing the potential severity of medication administration errors (MAEs) in Brazil. Thirty healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses and pharmacists) from Brazil were invited to score 50 cases of MAEs as in the original UK study, regarding their potential harm to the patient, on a scale from 0 to 10. Sixteen cases with known harmful outcomes were included to assess the validity of the scoring. To assess test–retest reliability, 10 cases (of the 50) were scored twice. Potential sources of variability in scoring were evaluated, including the occasion on which the scores were given, the scorers, their profession and the interactions among these variables. Data were analysed using generalisability theory. A G coefficient of 0.8 or more was considered reliable, and a Bland-Altman analysis was used to assess test–retest reliability.

Results:

To obtain a generalisability coefficient of 0.8, a minimum of three judges would need to score each case with their mean score used as an indicator of severity. The method also appeared to be valid, as the judges’ assessments were largely in line with the outcomes of the 16 cases with known outcomes. The Bland-Altman analysis showed that the distribution was homogeneous above and below the mean difference for doctors, pharmacists and nurses.

Conclusion:

The results of this study demonstrate the reliability and validity of an existing method of scoring the severity of MAEs for use in the Brazilian health system.

2010-05-01·Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Is honey a well-evidenced alternative to over-the-counter cough medicines?

作者: Tuleu, Catherine ; Evans, Hywel ; Sutcliffe, Alastair

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) recently banned use of the most commonly used over-the-counter (OTC) cough remedies in children under 6 years of age, responding to concerns about their lack of efficacy and adverse effects. Their report recommends, as an alternative, ‘a warm drink of lemon and honey’.1

A sceptic might be prompted to ask whether this advice was:

grounded more in folklore and accepted orthodoxy than empirical evidence;

offered primarily to pacify not children but anxious parents who might feel disempowered and disconcerted by the MHRA's ruling?

A Cochrane systematic review2 investigating the effect of honey and cough identified only one randomized controlled trial.3 Undertaken in the United States by Ian Paul et al., the study received widespread press coverage when it was published in December 2007, attracting such headlines as ‘Honey beats cough medicine’ in The Guardian.4

The trial recruited 105 children aged 2–18 years with cough as a feature of an upper respiratory tract infection. They were given either a syringe-full of honey or honey-flavoured dextromethorphan (DM, a common constituent of OTC cough remedies), while a third group received an empty syringe (to act as a control). The children's parents then reported via a telephone survey on their child's cough and sleep disturbance. These observations were compared with those taken the night prior to treatment. Each group showed much improved cough and sleep quality from the previous night and this was especially the case in the honey group. The researchers concluded that ‘honey was the most effective treatment for all of the outcomes related to cough, child sleep and parent sleep’.

The study was strongly criticized by experts, not least on the NHS website, Behind the Headlines.5 The study was small-scale, short, subjectively reported, poorly controlled and supported financially by the US National Honey Board. In fact, pairwise comparison of the honey and DM group revealed no statistically significant differences for any outcome. The study's only statistically significant results – that honey reduced cough frequency and overall cough score more than an empty syringe – might easily be attributed to the placebo effect alone. The Guardian subsequently printed a correction recognizing that its article was misleading.

So why is the MHRA giving advice based on such substandard evidence? It could be argued that this is consistent with the agency's practice regarding other ‘natural remedies’, such as its provision of licences for homeopathic products sold in UK pharmacies. At least we can be quite sure that the latter are free from side-effects. Like all other evidence-based interventions, whatever benefit is to be conferred by honey must be balanced against its potential risks, including dental caries, anaphylaxis, insomnia and hyperactivity. It would be an unwelcome situation if patients and healthcare professionals were unable to trust the government's medicines regulator in this matter.

The MHRA may have hoped that promoting traditional home remedies would alleviate parental concerns about the ruling made about OTC cough medicines. Perhaps there is an argument to be made in favour of advising use of a placebo by patients who are seeking treatment for a problem for which medicine has little to offer, if only to avoid the unwanted side-effects of ‘real’ medicines. However, this potential benefit compares badly with the risks of misleading patients and threatening to compromise the medical profession's core ethical values. We properly uphold the need for an honest and non-paternalistic approach to healthcare delivery, emphasizing informed and shared decision-making. This approach is equally applicable in treating young children as it is the informed decision of the parental guardian, not the healthcare professional, which determines the care that the child receives.

In the MHRA's documentation relating to its ruling on OTC cough remedies, it notes that ‘coughs occur frequently in children but they are self-limiting and rarely harmful’.6 However, each year ‘12 million packs [of such products] are sold with indications authorised for children less than six years of age’.7 In the UK, the total population of children under six years old is approximately 3.6 million. The millions of pounds that were spent on these products is testimony to the scale of the problem as perceived by parents. It represents the most common presenting complaint in general practice,8 results in millions of lost school and work days, and is a significant source of stress to both children and their carers alike.

We have then a noteworthy problem but the solution proposed by the MRHA lacks supporting evidence. This often happens when a potential solution is neither patentable nor particularly expensive. Since Paul's publication, research into honey as a treatment for cough has come to a standstill. As a consequence, we are left with the somewhat unsatisfactory conclusion that ‘for those who choose to offer therapy to children with cough … honey may be a reasonable option given its low cost, relatively low adverse effect profile, and potential benefit’.9

Without further credible evidence, healthcare professionals advocating honey as a treatment for cough could be considered reckless. The Cochrane Collaboration recognizes the need for more substantial evidence regarding the effectiveness of honey in resolving acute cough in children. The 2nd International Cough Symposium concluded that there is a great need for effective new cough treatments.10 What we need here is a well-designed, sufficiently powered, randomized controlled trial using a simple cough assessment tool to assess the effect of honey over a suitable period of time on children with cough as a feature of an upper respiratory tract infection. I suggest that many parents would ask us to make a beeline for this outcome as a matter of some urgency.

2010-04-01·Nanomedicine (London, England)

Nanorobots for Medicine: How Close Are We?

Article

作者: Kostarelos, Kostas

Since the pioneering vision of Feynman in his now famous lecture ‘There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom’ first delivered at an American Physical Society meeting at Caltech in December 1959 [1], film and scientific exploration at the nanoscale have been lending each other imagery and targets to achieve. It took only 5 years from Feynman’s lecture for a fellow resident of Los Angeles, Harry Kleiner, to complete the script for the film ‘The Fantastic Voyage’ that was released in 1965 to popularize ‘miniaturization for medicine’ like no scientist could ever do. The inspirational power of miniaturizing matter to navigate throughout the human body and reach the brain to remove aneurysm-causing blood clots depicted in the film, even transcended into the art world thanks to Salvador Dali and his painting ‘Le Voyage Fantastique’ portraying the voyage in to the human subconscious, a result of the painter’s direct involvement in the production of the film (Figure 1). Today, 45 years after this first cinematography-originated use of nanotechnology for medicine, numerous scientists, thinkers, film makers and authors have been describing how this powerful technology can assist us to explore the nanoscale of the human body. However, one question still persists. Where do fantasy, imagination and science fiction stop and where does ‘real’ science and medicine start? The answer is that even though dramatic developments in technology and engineering at the nanoscale have occurred in the last decade, we are still at a state of infancy regarding the capability to design, manufacture, control and navigate nanorobots (nanomachines, nanobots, nanoids, nanites and nanonites or however else described) and purposefully use them for diagnosis or therapy. Some of the most critical challenges are discussed below.

100 项与 The School of Pharmacy University of London 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 The School of Pharmacy University of London 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

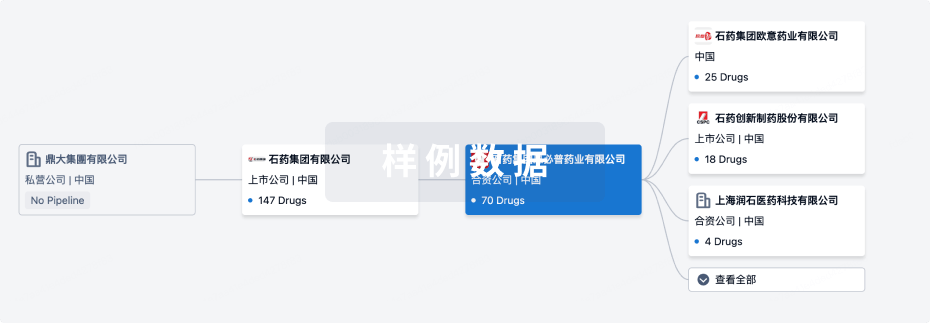

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2025年09月30日管线快照

管线布局中药物为当前组织机构及其子机构作为药物机构进行统计,早期临床1期并入临床1期,临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

其他

1

登录后查看更多信息

当前项目

| 药物(靶点) | 适应症 | 全球最高研发状态 |

|---|---|---|

ZP-281-M ( Bacterial DNA gyrase x Top II ) | 肿瘤 更多 | 无进展 |

登录后查看更多信息

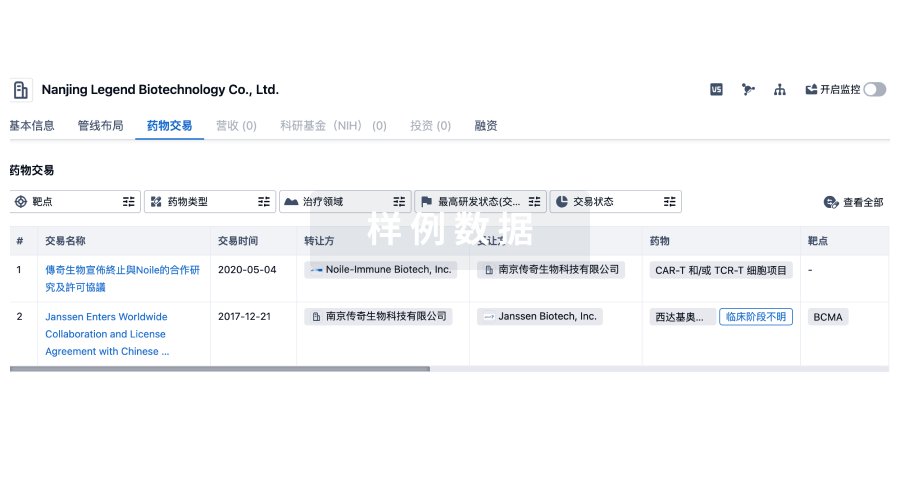

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

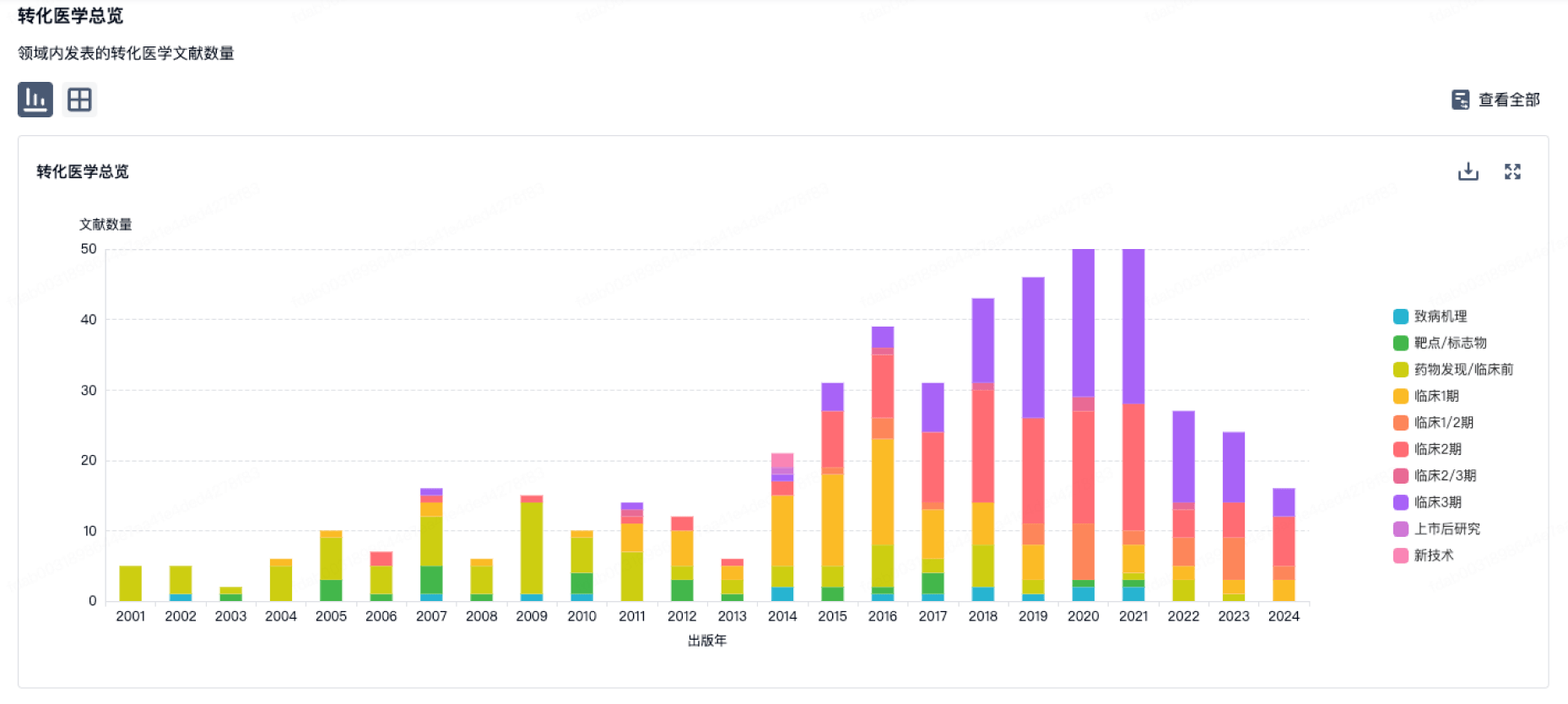

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

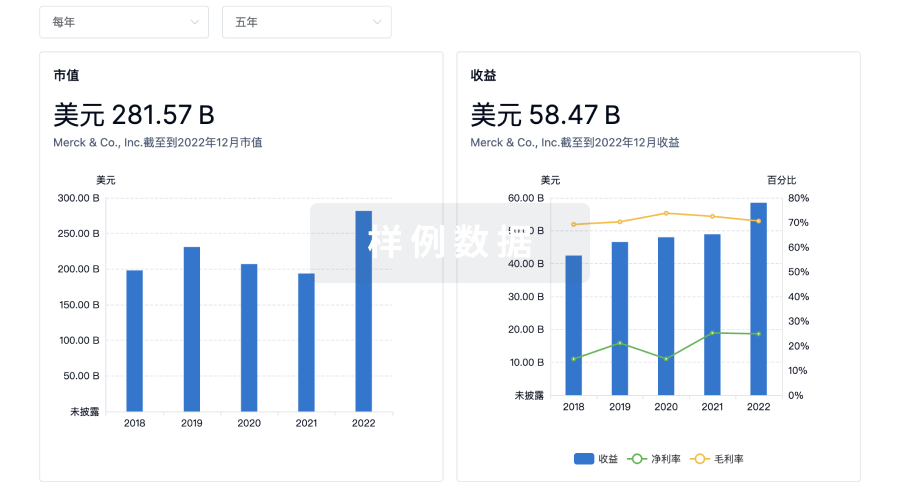

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

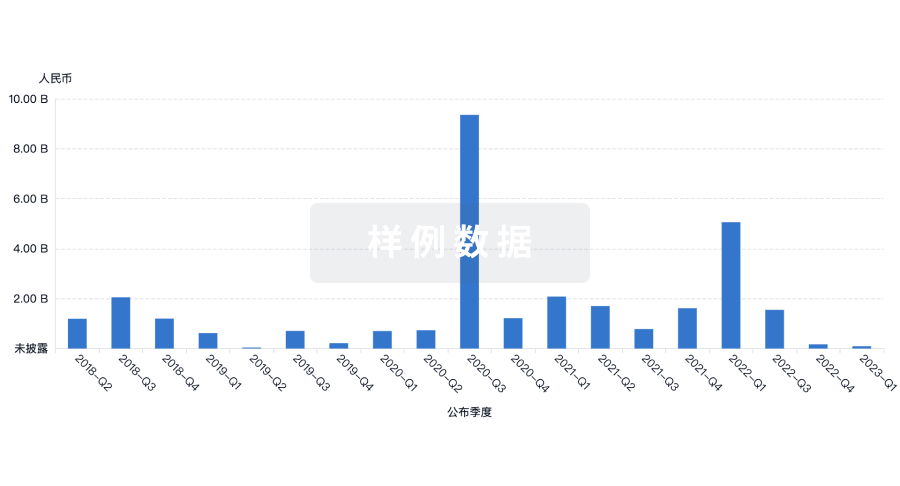

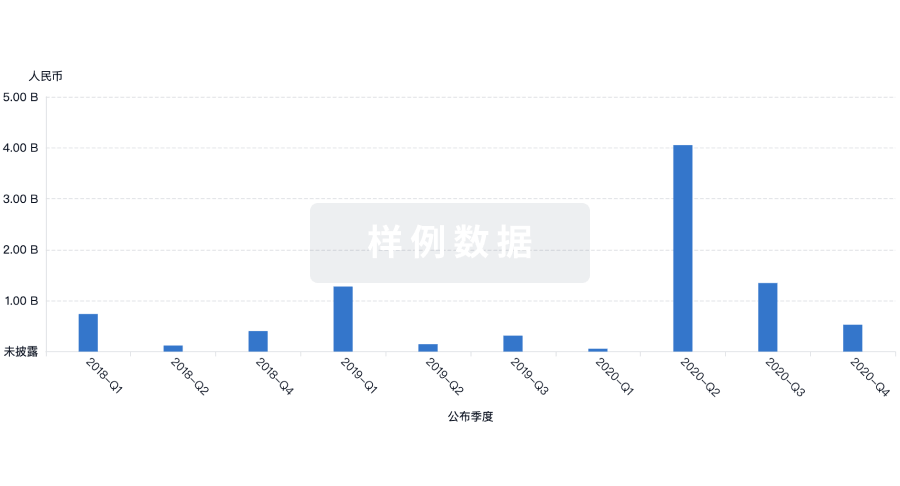

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

Eureka LS:

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用