更新于:2024-11-01

Mammoth Biosciences, Inc.

更新于:2024-11-01

概览

标签

神经系统疾病

遗传病与畸形

内分泌与代谢疾病

腺相关病毒基因治疗

CRISPR/Cas

疾病领域得分

一眼洞穿机构专注的疾病领域

暂无数据

技术平台

公司药物应用最多的技术

暂无数据

靶点

公司最常开发的靶点

暂无数据

| 排名前五的药物类型 | 数量 |

|---|---|

| 腺相关病毒基因治疗 | 2 |

| CRISPR/Cas | 1 |

| 排名前五的靶点 | 数量 |

|---|---|

| APOC3(载脂蛋白C-Ⅲ) | 1 |

关联

3

项与 Mammoth Biosciences, Inc. 相关的药物靶点 |

作用机制 APOC3调节剂 |

在研机构 |

原研机构 |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

靶点- |

作用机制- |

在研机构 |

原研机构 |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

靶点- |

作用机制- |

在研机构 |

原研机构 |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期- |

100 项与 Mammoth Biosciences, Inc. 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 Mammoth Biosciences, Inc. 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

11

项与 Mammoth Biosciences, Inc. 相关的文献(医药)2023-10-26·mSystems

Identification of hidden N4-like viruses and their interactions with hosts

Article

作者: Chen, Feng ; Shao, Hongbing ; Jiao, Nianzhi ; Wang, Min ; Liang, Yantao ; Suttle, Curtis A ; Sung, Yeong Yik ; McMinn, Andrew ; He, Jianfeng ; Zhang, Yu-Zhong ; Zheng, Kaiyang ; Tian, Jiwei ; Paez-Espino, David ; Gao, Chen ; Zou, Xiao ; Mok, Wen Jye ; Wong, Li Lian

2022-08-01·iScience

Virioplankton assemblages from challenger deep, the deepest place in the oceans

Article

作者: Zhang, Yu-Zhong ; Shi, Yang ; Liu, Fengjiao ; Yang, Yumei ; Xin, Yu ; Guo, Cui ; Xing, Jinyan ; Zhou, Chun ; Gu, Chengxiang ; McMinn, Andrew ; Tang, Xuexi ; Yang, Qingwei ; Suttle, Curtis A ; He, Hui ; Shao, Hongbing ; Gao, Chen ; Paez-Espino, David ; Wang, Min ; Luo, Zhixiang ; Liang, Yantao ; Zhang, Xinran ; Qin, Qilong ; Han, Meiaoxue ; Gong, Zheng ; Jiao, Nianzhi ; Wang, Meiwen ; Jiang, Yong ; He, Jianfeng ; Tian, Jiwei

2021-04-27·mSystems2区 · 生物学

Uncultivated Viral Populations Dominate Estuarine Viromes on the Spatiotemporal Scale

2区 · 生物学

ArticleOA

作者: Páez-Espino, David ; Marsan, David ; Sun, Mengqi ; Zhan, Yuanchao ; Chen, Feng ; Cai, Lanlan

83

项与 Mammoth Biosciences, Inc. 相关的新闻(医药)2024-10-20

导读

在基因编辑和CRISPR技术的世界里,詹妮弗·A·杜德纳(Jennifer A. Doudna)无疑是一位举足轻重的科学家。

她的生涯不仅仅是关于实验室的研究,更是关于如何将这些研究成果转化为能够改变世界的实际应用。从发现CRISPR到领导开创性的临床试验,詹妮弗博士一直在打破科学的边界,为治疗遗传性疾病开辟新的道路。

她的工作不仅展示了科学的力量,也为我们提供了对未来医疗的无限想象。在这篇自述中,我们将跟随詹妮弗博士的脚步,探索她的科研旅程,以及她如何成为这一领域的领军人物。

本文为其在诺贝尔奖网站撰写的自传(https://www.nobelprize.org/)。

1964年2月19日,我在华盛顿特区出生,是家中的老大,我还有两个妹妹。我父亲马丁·K·杜德纳(Martin K. Doudna )是当时美国国防部的演讲稿撰写人,而我母亲多萝西(Dorothy)则在社区学院任教。之后,我们全家搬到了安娜堡(密歇根大学所在地),我父亲在那里攻读文学博士学位。1971年8月,当我七岁的时候,他收到了夏威夷希洛大学的工作邀请,于是我们全家又搬到了那里。

作为一个“白人”(夏威夷俚语,指非土著人),我在成长过程中在学校里总是有一种孤独或被孤立感。这种“局外人”的感觉促使我去冒险,去证明怀疑者是错误的,而这一点也影响了我后来作为科学家的选择。在我孤独的时候,书籍给予了我安慰,它们激发了我去探索周围世界并融入其中。随着我结交朋友并扩展社交生活,我通过徒步旅行、骑自行车、探索熔岩洞穴等活动丰富了我的阅读经历。夏威夷的“大岛”拥有火山、森林和海滩的混合景观,提供了丰富的生物多样性,激发了我对生物多样性起源问题的最初思考。

六年级时,我偶然发现了父亲放在我床上的一本书,书名是詹姆斯·沃森(James Watson)所著的《双螺旋》。书中讲述了美国生物学家沃森和英国生物化学家弗朗西斯·克里克(Francis Crick)如何在1953年发现了DNA分子的螺旋结构,他们因此与莫里斯·威尔金斯(Maurice Wilkins)共同获得了1962年的诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

DNA由核苷酸链组成,每个核苷酸都包含四种氮碱基之一——腺嘌呤、胸腺嘧啶、鸟嘌呤和胞嘧啶。所有执行生命必需过程的信息都编码在这些AGTC碱基字母的序列中。一串包含制造特定蛋白质指令的碱基字母序列被称为基因。《双螺旋》解释了DNA的双链螺旋结构——通常被描述为一种“可以解开的扭曲梯子”——如何暴露其AGTC字母序列,从而使它们携带的遗传指令能够被复制到信使RNA(mRNA)上。在人类等真核生物的细胞中,mRNA将这些指令从细胞核传递到细胞质,在那里转运RNA(tRNA)利用这些信息将氨基酸组装成蛋白质。

在阅读《双螺旋》时,我被科学家们如何通力协作,精心拼凑并解决了生物学中最难解的谜团之一的过程所吸引。

在书中,罗莎琳德·富兰克林(Rosalind Franklin)通过X射线晶体学图像揭示了DNA的螺旋形状,在了解到这位被誉为‘DNA的黑暗女神’所发挥的作用后,我第一次意识到女性也可以成为伟大的科学家。

尽管我的学术成绩出类拔萃,特别是在数学和科学方面,但我的高中指导老师强烈反对我攻读化学专业,甚至让我不要梦想成为一名科学家。然而,我并未因此退缩,而是申请了加利福尼亚州波莫纳学院的化学专业,并在1981年秋季以17岁的年龄顺利入学。尽管我曾短暂地考虑过转攻法语专业,但最终我仍坚持学习化学。

那年夏天,我回到希洛,在唐·赫姆斯(Don Hemmes)的实验室工作,他是一位生物学教授,也是我们家的老朋友。我被分配到一个小组,研究一种名为Phytophthora palmivora的真菌如何感染木瓜,这对夏威夷的果树种植者来说是一个大问题。我学会了如何为电子显微镜分析准备样本,并观察了真菌在不同萌发阶段发生的化学变化。这项研究揭示了钙离子在真菌发育中的关键作用,它们通过向真菌细胞发出信号,使其在营养物质的刺激下生长。这是我第一次体验到科学发现的乐趣,之前这种乐趣仅局限于我的阅读体验中,而这次实践活动让我更加渴望去探索更多科学的奥秘。

1984年夏天,经过大二和大三两年的学习,我对科学的热爱更加坚定,因此受邀加入我的导师莎朗·帕纳森科(Sharon Panasenko)生物化学教授的实验室工作。我的任务是培养基于土壤的细菌,以便我们能够研究使细菌在缺乏营养时自我组织成菌群的化学信号。我在大型烤盘中培养细菌,而不是使用传统的培养皿,这一方法得到了莎朗在《细菌学杂志》上发表的一篇论文的认可,这也是我的名字首次出现在科学期刊上。

1985年春天,我以化学专业最高分的成绩从波莫纳学院毕业。我非常感谢波莫纳学院提供的人文教育,让我接触到了许多我从未接触过的想法,这些想法对我后来的成功至关重要。

在父亲的鼓励下,我申请了哈佛医学院的研究生院,并于1985年秋天入学。1986年,我选择在杰克·索斯塔克(Jack Szostak),他于2009年与伊丽莎白·布莱克本(Elizabeth Blackburn)和卡罗尔·格雷德(Carol Greider)一起获得诺贝尔生理学或医学奖,我进入了他的实验室进行论文工作,他发现了端粒帽如何防止染色体分解。

杰克正在将他的研究重点从DNA转向RNA,以及RNA在地球生命起源中所扮演的角色。他怀疑RNA早于DNA出现,并鼓励我做他的第一名研究生,共同探索这一想法。

回想起来,在当时我做出专注于RNA的决定是完全合理的,但远离DNA是一个大胆且冒险的举动,因为当时公众的目光都聚焦到了人类基因组计划,这是一个国际性的大计划,旨在绘制和测序人类基因组(一个生物体的全部DNA)中的所有碱基字母。

被誉为“生物学的圣杯”的人类基因组计划承诺,它所提供的丰富遗传信息将彻底改变医疗诊断和治疗。绘制和测序DNA是多数研究人员首要选择的项目,也更容易获得资金支持,但我们看到了从更好地了解多功能RNA分子的所有形式所具备的巨大价值。

杰克和我一致认为,RNA在生命起源中可能发挥了重要作用,这取决于RNA分子是否能够自我复制。为了回答这个问题,我们将一个自我剪接的RNA内含子(一种不编码蛋白质的DNA或RNA分子片段)重新改造为一种RNA酶(一种蛋白质催化剂),该酶可以拼接其自身的副本。这表明RNA可以作为聚合酶,一种促进形成DNA或RNA等分子的酶。我们在1989年的《自然》杂志上发表了题为“RNA催化的互补链RNA合成”的研究结果,这标志着我RNA研究的开始。

1989年获得博士学位后,我继续在杰克的实验室作为博士后研究员研究自我复制的RNA分子,但我的好奇心却在“什么样的分子结构能使RNA自我复制”上。这是生物学领域最艰难的挑战之一,即确定RNA酶和其他功能性RNA分子的分子结构。

1991年夏天,我搬到了科罗拉多大学波尔得分校,在汤姆·塞奇(Tom Cech)的实验室工作。在那之前,塞奇与合作者西德尼·奥特曼(Sidney Altman)共同获得了诺贝尔化学奖。在20世纪80年代,他们发现RNA不仅作为遗传信使,还可以像酶一样发挥作用。他们将这种催化RNA称为“核糖酶”,这是通过将“核糖核酸”与“酶”结合起来命名的。他们的核糖酶就是我和杰克后来重新设计的自我复制的RNA酶。

作为汤姆实验室的研究员,我使用X射线晶体学成像RNA酶的结构,这与罗莎琳德·富兰克林(Rosalind Franklin)成像DNA结构的方式类似。为了这项工作,我与一位名叫杰米·凯特(Jamie Cate)的研究生合作,此前他一直在使用X射线晶体学研究蛋白质结构。尽管我们成功地使RNA酶结晶以供成像,但X射线的照射迅速破坏了晶体结构。

多亏了一次偶遇,我得以学习到用于在X射线成像前对晶体进行低温冷却的技术。有一次,我与耶鲁大学生物化学家托马斯·施泰茨(Thomas Steitz)以及他的妻子琼·施泰茨(Joan Steitz)夫妇的偶然相遇,施泰茨因确定核糖体的结构而获得了2009年诺贝尔化学奖,核糖体是细胞质中的大分子,利用RNA的遗传信息合成蛋白质。他们夫妻在波尔得分校休假一年。就是在这里,我学到了这项新的技术,在液氮中快速冷冻晶体可以保持其晶体完整性,即使受到X射线照射也是如此。

我渴望获取低温冷却技术,于是在1994年,我接受了耶鲁大学分子生物物理学和生物化学助理教授的职位,杰米·凯特(Jamie Cate)作为我的研究生随我一同前往我的新实验室。借助杰米开发的技术,我们使用X射线晶体学完成了电子密度图,让我们能够确定自我剪接RNA酶中每个原子的位置。有了这些信息,我们构建了分子的结构模型,类似于沃森和克里克对DNA所做的那样。

正如双螺旋结构揭示了DNA如何存储和传递遗传密码一样,我和团队构建的结构模型也揭示了RNA如何作为能够切割、拼接和复制自身的酶发挥作用。汤姆和我是这项研究的主要调查人员,而杰米则是1996年在《科学》杂志上发表的一篇题为“第一组核糖酶域晶体结构:RNA包装的原理”论文的主要作者。这篇论文被认为是科学界的一个里程碑,因为它首次详细观察了大型结构的核糖酶。我们当时希望,我们的发现能够为科学家未来如何修改核糖酶以修复缺陷基因提供线索。

1997年,我接受了霍华德·休斯医学研究所(HHMI)研究员的任命。2000年,我被任命为亨利·福特二世(Henry Ford II)分子生物物理学和生物化学教授,并被选入美国国家科学院。那年夏天,我和我的研究伙伴杰米·凯特(Jamie H. D. Cate)结婚,两年后我们有了一个儿子,我们给他取名安德鲁(Andrew)。2002年,杰米和我接受了加州大学伯克利分校(UC Berkeley)化学学院的教授职位。我们还成为劳伦斯伯克利国家实验室(Berkeley Lab)的科学家,这让我们有机会使用高级光源,这是世界上首屈一指的用于晶体学研究的X射线源之一。

2002年秋天,我刚开始在加州大学伯克利分校工作时,中国爆发了一场由RNA病毒引起的严重急性呼吸道综合征(SARS)。这次疫情促使我转向RNA干扰的研究,这是一种在许多重要功能中起基本作用的现象,包括人类免疫系统如何抵抗病毒感染。RNA干扰会沉默不需要的遗传信息,从而阻止它们编码的蛋白质的产生。

利用高级光源中强大的光束和精密的仪器,这是一台专为X射线和紫外线研究优化的同步加速器,我的实验室和我制作出了晶体学图像,从中我们确定了一种名为Dicer的酶起着分子尺子的作用,可以切割双链RNA并启动RNA干扰过程。我们发现,Dicer的分子结构在一端有一个“夹子”来抓住双链RNA分子,而在另一端则有一个“切割器”以一定的距离切割它。

我们的发现为理解Dicer酶如何参与RNA干扰通路的其他阶段奠定了基础,为重新设计指导特定基因沉默途径的RNA分子提供了指导。我们的工作后来促使加州大学伯克利分校微生物学家吉莉安·班菲尔德(Jillian Banfield)给我打来电话,她首次向我介绍了“CRISPR”这个词。

吉莉安正在研究生活在极端环境中的微生物的基因组学,以期找到更好的清理污染场所的方法,她多次遇到了被称为CRISPR(Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats,即规律性成簇间隔短回文重复)的DNA碱基序列单元或长度,它在微生物如细菌和古菌的防御机制中发挥作用,保护它们免受病毒和被称为质粒的入侵核酸链的侵害。CRISPR单元通常位于微生物的染色体上,由称为“重复”和“间隔”的碱基序列组成,这些序列将重复的序列分隔开。吉莉安对理解CRISPR和一种被称为“Cas”的相邻酶复合物(即CRISPR相关蛋白)如何共同作用,使微生物能够利用小型定制RNA分子(crRNA)通过基因沉默过程保护自己感到兴趣。吉莉安通过谷歌搜索找到了我实验室的网站,并建议开展合作,以了解CRISPR-Cas免疫系统如何通过RNA干扰发挥作用。

之后,我们在伯克利当地的一家咖啡馆边喝茶边交谈,讨论了CRISPR这一新的、神秘的生物学功能,以及它可能是RNA干扰的细菌等价物的可能性。虽然有关CRISPR的假说已经浮出水面,但还没有人进行过实验来证实或反驳这些理论。

2008年,我和吉莉安以及蒙大拿州立大学的马克·杨(Mark Young)组织了第一次关于CRISPR研究的国际会议,会议在伯克利举行。同年,西北大学的研究发现CRISPR-Cas系统并非通过RNA干扰起作用,而是将目标锁定在入侵者的DNA上。这一发现的含义十分重大。如果CRISPR-Cas能够识别、锁定并切割侵入性DNA,那么它就有潜力成为一种DNA编辑工具。然而,关键的实验信息仍然缺失,特别是关于CRISPR-Cas系统如何能够识别和切割不需要的DNA的信息。

我的实验室团队开始致力于填补这些缺失的信息,首先我们开发了一种纯化技术,为他们提供了高浓度的Cas蛋白样本,这是他们想要研究的。利用这种技术,我们首先研究了Cas1,我们发现它能够以某种方式切割DNA,有助于在免疫系统形成记忆阶段将新的外源DNA片段插入CRISPR单元。这使我们离理解CRISPR如何从攻击性噬菌体中窃取DNA片段并将其融入自身更近了一步,为免疫反应的靶向和破坏阶段奠定了基础。

2010年,我们在先进光源的X射线晶体学光束线上制作了Cas6f的首个原子尺度晶体结构模型,发现它与Cas1一样,可以充当化学切割剂。然而,我们发现Cas6f的工作是专门且有条不紊地将长CRISPR RNA分子切割成较短的片段,这些片段可用于靶向外源DNA。

我们的模型显示,当微生物识别出其已被外源DNA入侵时,它会将一小段外源DNA整合到其CRISPR单元之一中,该单元随后被转录为称为pre-crRNA的长RNA片段。Cas6f在每个重复元素内切割这种pre-crRNA,以产生包含与外源DNA部分匹配的序列的短crRNA,供Cas蛋白结合外源DNA并使其沉默。这些研究结果发表在《科学》杂志上,题为《Sequence- and structure-specific RNA processing by a CRISPR endonuclease》。

2011年,我在波多黎各举行的美国微生物学会年度会议上遇到了埃曼纽尔·夏彭蒂耶(Emmanuelle Charpentier)。埃曼纽尔是一名法国生物化学家、微生物学家和遗传学家,也是世界上顶尖的CRISPR-Cas研究人员之一。当时,她正在瑞典乌普萨拉大学分子感染医学实验室研究被称为II型的CRISPR系统中的Cas9。她的研究表明,在人类病原体化脓性链球菌中,只有在存在第二种CRISPR RNA分子,即反式激活crRNA的tracrRNA时,才能产生crRNA,而CRISPR系统只需要Cas9即可获得对由crRNA靶向的病毒的免疫力。

埃曼纽尔和我开始合作,调查Cas9和crRNA在CRISPR微生物免疫系统中如何发挥作用,以及是否可以将crRNA和tracrRNA链接成一个单一的嵌合CRISPR RNA分子,从而使系统更易于操作。

我和我的实验室成员马丁·金尼克(Martin Jinek)和迈克尔·豪尔(Michael Hauer),以及埃曼纽尔实验室的克里斯托夫·奇林斯基(Krzysztof Chylinski)和伊内斯·冯法拉(Ines Fonfara)一起,揭示了CRISPR-Cas9组装的组件。在我们发现Cas9需要与tracrRNA和crRNA的分子复合物结合,然后识别和引导Cas9到入侵的DNA进行切割的过程中,我们意识到tracrRNA和crRNA复合物是可编程的。

下一步是设计一个单引导RNA(sgRNA)分子,一端包含引导信息,另一端包含结合把手。这样的系统将为切割基因组中任何所需的DNA序列段提供一种简单的方法。然后,可以使用已建立的细胞DNA重组技术将新的遗传信息引入基因组。

2012年8月17日,这项具有里程碑意义的研究结果发表在《科学》杂志上(首次在线发表于2012年6月28日)。论文标题为《A Programmable Dual-RNA–Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity》。埃曼纽尔和我是主要研究人员;共同作者包括马丁、克里斯托夫、伊内斯和迈克尔。

我们的论文表明,经过数亿年的进化,细菌和其他微生物为了防御病毒和其他入侵DNA而发展的免疫系统,可以被改造成相对易于使用的“CRISPR基因编辑”技术,以无与伦比的效率和精确度重写任何生物体(包括人类)细胞内的遗传代码。

这是一段令人难以置信、珍贵而纯粹的快乐时光,我们发现细菌并找到了一种方法,可以编程一种战士蛋白来寻找并破坏病毒DNA,我们能够重新利用这一基本属性用于完全不同的用途,这更是幸运,甚至是一种奇迹。发现带来的喜悦与我在夏威夷与唐·赫姆斯(Don Hemmes)共事多年前的实验室里感受到的感觉一模一样。

2014年,我与乔纳森·韦斯曼(Jonathan Weissman)共同创立了创新基因组学研究所(Innovative Genomics Institute,简称IGI),以实现CRISPR基因编辑在人类健康、气候和农业方面的潜力。我担任所长的IGI由加州大学伯克利分校和加州大学旧金山分校的研究人员组成,他们正在开发基础性CRISPR技术,以促进人类受益的基因工程创新,同时使这些技术能够造福全人类并价格合理。我们继续努力将最初的好奇心驱动的基础发现项目转化为帮助改善人类状况的策略。

IGI早期倡议之一的重点是扩大镰状细胞病的治疗途径。此时,我已经创办了我的第一家公司Caribou Biosciences,并会共同创立Editas Medicine、Intellia Therapeutics、Mammoth Biosciences和Scribe Therapeutics等公司,将CRISPR从实验室带入诊所,以CRISPR为基础的治疗和诊断形式。

我接受了加州大学伯克利分校、Gladstone研究所高级研究员以及加州大学旧金山分校细胞与分子药理学兼职教授等职务,继续研究CRISPR基础疗法的输送技术、下一代CRISPR诊断技术的开发,以及CRISPR-Cas系统的结构和机制调查。我们能够利用CRISPR巨大的“双重用途”潜力,使我决定积极参与并启动关于CRISPR的伦理使用和负责任监管的公众讨论,特别是在人类生殖系编辑的情况下。

2015年,我首次呼吁暂停在人类生殖系中使用CRISPR,并与另外20名研究人员安排了一次会议,讨论生殖系基因编辑的伦理问题。这次纳帕谷会议以1975年的阿西洛马尔会议为榜样,阿西洛马尔会议曾为重组DNA研究提出了指导方针,并与其中两位关键组织者保罗·伯格(Paul Berg)和大卫·巴尔的摩(David Baltimore)共同组织。我们在纳帕谷会议上进行的讨论被总结在后来发表在《科学》杂志上的一份报告中。我们概述了人类生殖系编辑的影响,并最终呼吁采取谨慎的道路,包括制定明确的国际指导方针,而不是仅仅实施暂停。

2015年12月,我成为了国际人类基因编辑峰会的组织者之一,这是美国国家科学院首次举行的关于CRISPR技术的社会与伦理应用的国际研讨会。在会上,我们进一步讨论了安全应用CRISPR技术的伦理考量,并达成了与纳帕会议相似的共识——在人类生殖系编辑被允许之前,必须满足某些条件。随着CRISPR开始进入主流对话,2017年,我与塞缪尔·斯特恩伯格合著的《创造中的裂痕:基因编辑与不可思议的控制进化力量》一书中详细阐述了我们所面临的伦理困境,以及我们呼吁科学家、生物伦理学家和更广泛的公众持续参与的原因。我希望我和萨姆描述的步骤能阻止任何过早尝试进行可遗传基因编辑的行为,但仅仅一年后,我所担心的那种轻率实验就发生了。

2018年,在香港举行的第二届国际人类基因组编辑峰会上,出现了中国首例“CRISPR婴儿”诞生的消息——这是一种医学上不必要的、非法的人体实验——将我们推入了一个新时代。我和我的同事,包括国家科学院和医学科学院以及英国皇家学会的许多成员,其中许多人参加了2015年的纳帕谷会议,我们一致认为,生殖系编辑的风险仍然太大,不能允许在胚胎、卵细胞或精子细胞中进行基因编辑。回到美国后,我与多位参议员会晤,讨论CRISPR技术最安全的发展路径——以及其对我们健康的未来影响——并继续引导关于必要法规的对话,包括随后由美国科学院和世界卫生组织召开的国际委员会。

2020年初,随着全球新冠疫情的爆发,我扩大了与CRISPR相关的工作。我和我的IGI同事在2020年3月,仅用了三周时间,就在我们的研究设施基础上建立了一个自动化的冠状病毒临床检测实验室。自那以来,我们的团队已经为当地和州级社区的数千人提供了关键的检测服务。此外,我们还启动了一项新计划,旨在开发一种基于CRISPR的快速、现场诊断测试,并推出了大约20多个其他研究项目。我们意识到需要进一步加强科学合作和创新,以帮助我们摆脱疫情,因此我们发布了一份路线图,详细阐述了将我们的非临床实验室转变为检测设施的过程,并将所有与COVID-19项目相关的知识产权开放源代码。

我们的团队继续致力于基因组工程研究,以提高全球患者的护理标准,并解决目前尚未满足的最高需求。从埃马纽埃尔和我共同发现CRISPR,到目前正在发生的基因组编辑革命,我们迄今为止的努力被畅销书作家和历史学家沃尔特·艾萨克森在他的2021年3月出版的《解码者:詹妮弗·杜德纳、基因编辑和人类未来》一书中记录了下来。不久后,IGI领导了一个由加州大学伯克利分校、加州大学旧金山分校和加州大学洛杉矶分校的科学家和医生组成的联合体,开始了首个经美国食品和药物管理局批准的基于CRISPR疗法的临床试验,用于直接纠正导致镰状细胞病的基因突变。我们正在开发镰状细胞疗法和未来的CRISPR基因疗法,最终目的是从人体内部(体内)治疗疾病,并扩展到血液癌症、免疫性疾病和其他目前无法治疗的罕见疾病。通过提高我们重写生命密码的能力,并支持使我们发现CRISPR成为可能的基础科学研究,我相信这些疾病很快就可以得到解决。

原文链接:https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2020/doudna/biographical/

识别微信二维码,添加生物制品圈小编,符合条件者即可加入

生物制品微信群!

请注明:姓名+研究方向!

版

权

声

明

本公众号所有转载文章系出于传递更多信息之目的,且明确注明来源和作者,不希望被转载的媒体或个人可与我们联系(cbplib@163.com),我们将立即进行删除处理。所有文章仅代表作者观点,不代表本站立场。

信使RNA基因疗法寡核苷酸

2024-10-11

A small venture capital firm that backs up-and-coming scientists plans to raise a $35 million second fund, three years after coming onto the scene.

SciFounders, based in the San Francisco Bay Area, is seeking its second fund, according to an SEC document

filed

Thursday. The fund declined to comment on the filing and the proposed raise, which has yet to mark its first sale.

SciFounders emerged in January 2021 with $6 million, according to

TechCrunch

, to help scientist founders lead their own startups. The fund is led by several entrepreneurs who have co-founded their own companies. This includes

Mammoth Biosciences

chief scientific officer

Lucas Harrington

and

Conception

CEO Matt Krisiloff. Former Genentech researcher Alexander Schubert is also a leader of SciFounders.

“We think it would be great longer-term for scientists to say, ‘We’re first-class citizens in charge of everything,’ as is often the case in the software world, where you have the Collison brothers in charge of Stripe, or the Airbnb founders in charge of their company,” Krisiloff told TechCrunch in 2021. “We want to make sure that happens more widely for scientist founders, as well.”

On its website, the fund says it typically backs early-stage companies and takes about a 10% stake for pre-seed and seed-stage investments.

Its portfolio includes Deliver Biosciences, which is working on delivery particles for cell and gene therapies;

Symphony Biosciences

, a Los Angeles upstart creating sponge-like devices for treating solid tumors; and Fletcher Biosciences, a Cambridge, MA-based startup developing protein therapies for T cells.

Other biotech VC firms like Curie.Bio, which operates under the motto “

Free the Founders,

” have also placed an emphasis on supporting scientific founders in recent years. Curie has said it invests about $5 million to $7 million in seed rounds, and its drug discovery counterpart gets about a 7% stake in exchange for its services.

2024-09-04

Nicole Bean for

BioSpace

The intellectual property landscape for newer gene-editing technologies, like that for CRISPR-Cas9, remains unclear and hard to navigate.

Years of litigation

around ownership of CRISPR-Cas9 have muddled the patent landscape for the Nobel Prize–winning technology. Meanwhile, hopes that newer gene editors would avoid this uncertainty have been dashed, as even here, the intellectual property around them remains “clear as mud,”

Matthew Ferry

, a partner at Morrison Foerster’s San Diego office, told

BioSpace

.

Nevertheless, these uncertainties have not deterred companies from developing gene editors, and specifically from pursuing Cas9 alternatives in the hopes of avoiding the IP conflicts that currently center on the original CRISPR system.

“Whether that’s true or not isn’t so clear; it depends on how you read the claims of this,” Ferry said. “And the problem is we just don’t have a lot of data from courts interpreting what the claims really mean here.”

Appetite For Risk

The case all CRISPR companies have their eyes on is one that has been waging for over a decade between the Broad Institute, the current holders of key CRISPR-Cas9 patents in the U.S., and what is known collectively as the CVC group. The case is currently pending appeal, with a ruling expected from a federal court in the second half of this year. A clear victory will chart a path to Cas9 licensing for companies seeking to develop therapies using the technology. On the other hand,

for investors not much may change

, with any licensing fees they have to pay viewed as the cost of doing business offset by lucrative returns.

As a result of the legal uncertainty, Ferry said some companies are waiting to see the outcome of the interference case between Broad and CVC while others are moving forward anyway.

“You have others who are taking a much more risk hard approach, of just saying, ‘There hasn’t been a lot of litigation so I don’t think I’m going to get sued. I’m just going to do what I need to do,’” Ferry said.

Michalski Hüttermann & Partner patent attorney

Ulrich Storz

agreed that the patent landscape remains unclear for

newer CRISPR technologies

. However, he said that matters surrounding Cas9 became particularly complicated because around five different entities are claiming they made roughly the same invention in the same year.

“Cas12a or Cpf1 is a little less messy because you don’t have like five entities,” Storz told

BioSpace

. “It’s pretty clear that the main player in Cas12a is the Broad Institute with Feng Zhang.”

However, Storz said that the Broad Institute’s patents do not provide a sufficient definition of what they consider to qualify as the Cas12a endonuclease. With several companies claiming that their nucleases don’t fall under the patents’ scope, Storz said the lack of clarity in Broad’s IP makes it hard for patent practitioners to verify such claims.

“I am a little bit concerned and surprised that the patent authorities let Broad run away with patents in which the enzyme that was actually the subject matter of the claims was so poorly defined,” Storz said. He contrasted his view with what he described as “a really strong position” by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to demand that antibodies in patent claims are defined by their precise sequences and not solely by their function.

The Broad Institute did not respond to

BioSpace

’s requests for comment by deadline.

On the other hand, Ferry believes companies are distinguishing themselves more in their patent filings. “You have to show that your invention is novel and non-obvious over the prior art,” Ferry said. “So to do that, you become much more fragmented and find much more niche areas that either have unexpected results or have a completely new way of doing something.”

One of the lessons learned so far, Ferry noted, was that it’s easier to secure IP on the physical technology than the application of the natural biology. “There have been some claims out there that were more abstract that were shown to be not patentable. So they have taken a lesson from that and tied it to the physical embodiments.” Ferry explained that because products of nature are generally not patentable in the U.S., there’s been a stronger focus on distinguishing what is a human-made invention and what is a discovery of a natural phenomenon.

The complicated licensing situation is still top of mind for many companies working in this space, Ferry said, noting that right now, the companies he’s in contact with still want to know what their competitors are doing in terms of obtaining licenses.

“It is a patent thicket that’s out there, but they have a business to run at the end of the day,” Ferry said. “And you can’t be so risk intolerant that you no longer have a business to worry about.”

Is the Non-Cas9 Landscape More Straightforward?

Mammoth Biosciences

, a biotech company co-founded by Jennifer Doudna who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing the CRISPR-Cas9 system, is one of the companies banking on it being easier to secure IP for non-Cas9-based gene editors.

“We see the non-Cas9 landscape of truly differentiated systems, like those we’re building at Mammoth, as much more straightforward than Cas9 and Cas9-adjacent large systems, no matter the name,” a spokesperson for

Mammoth Biosciences

told

BioSpace

.

Mammoth is specifically using

ultracompact systems

distinct from Cas9 and has an extensive portfolio of wholly owned and licensed IP that is foundational to the non-Cas9 space, including Cas12f (CasZ), Cas12j (CasPhi), and NanoCas. MB-111, Mammoth’s lead therapeutic in development, is targeting familial chylomicronemia syndrome, a rare

life-threatening disease

that prevents the body from digesting fats and severe hypertriglyceridemia, which can lead to fatal pancreatitis. The research is in the lead optimization stage.

But, Ferry explained, just because an enzyme is not based on Cas9 doesn’t necessarily mean it’s free from the Broad or CVC portfolios. “That assumes a clear delineation between the IP portfolio and the enzyme, which isn’t always true,” he said. “There’s overlap between patents and a technology, but a patent can be broader than the specific technology that was the basis for it.”

In sum, he added, “it’s not clear. But you have a lot of people who think it is.”

专利侵权

100 项与 Mammoth Biosciences, Inc. 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

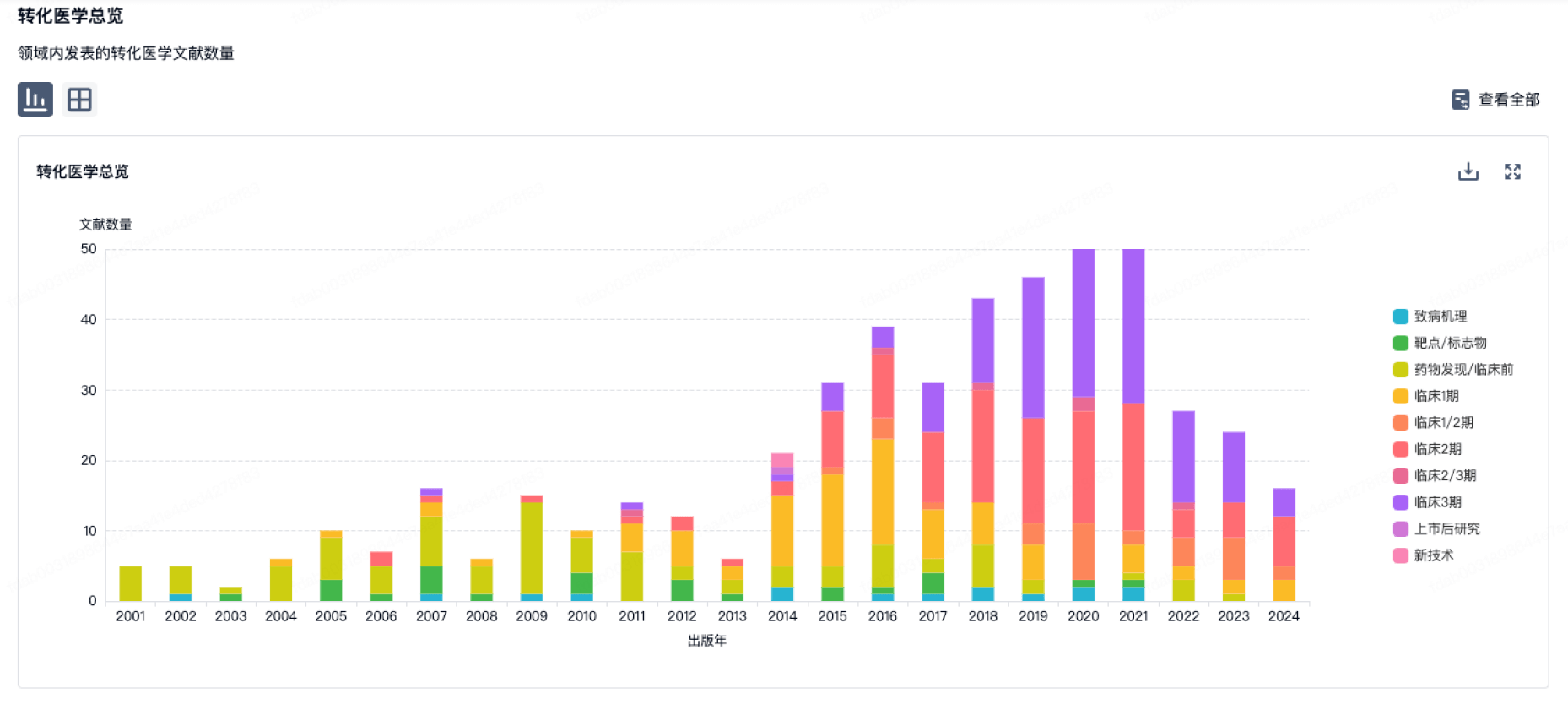

100 项与 Mammoth Biosciences, Inc. 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

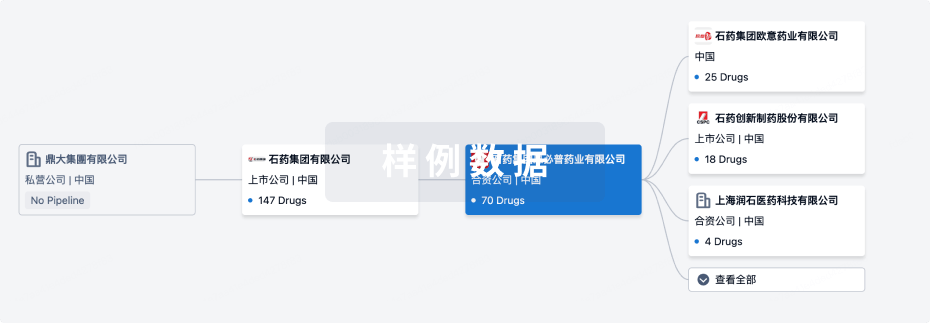

组织架构

使用我们的机构树数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

管线布局

2024年11月17日管线快照

管线布局中药物为当前组织机构及其子机构作为药物机构进行统计,早期临床1期并入临床1期,临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

临床前

3

登录后查看更多信息

当前项目

| 药物(靶点) | 适应症 | 全球最高研发状态 |

|---|---|---|

Neuromuscular disease(Mammoth) | 神经肌肉疾病 更多 | 临床前 |

MB-111 ( APOC3 ) | 家族性乳糜微粒血症综合征 更多 | 临床前 |

CNS disease(Mammoth) | 中枢神经系统疾病 更多 | 临床前 |

登录后查看更多信息

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

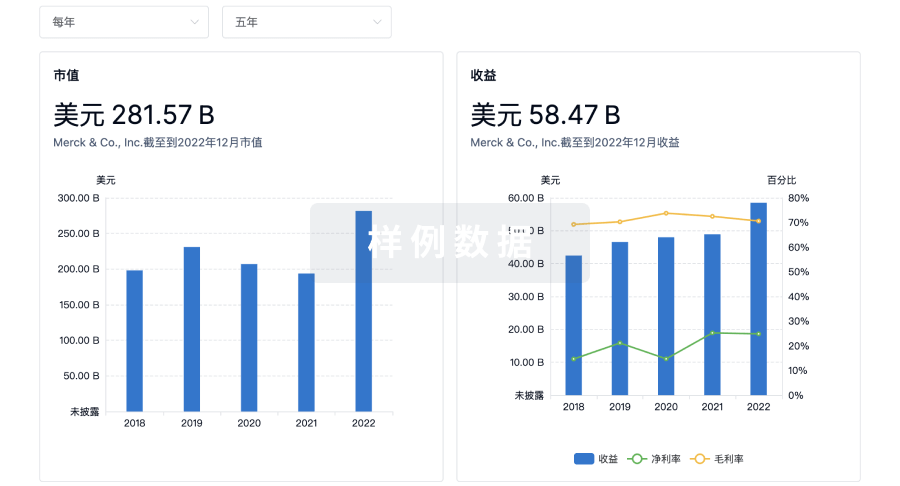

营收

使用 Synapse 探索超过 36 万个组织的财务状况。

登录

或

科研基金(NIH)

访问超过 200 万项资助和基金信息,以提升您的研究之旅。

登录

或

投资

深入了解从初创企业到成熟企业的最新公司投资动态。

登录

或

融资

发掘融资趋势以验证和推进您的投资机会。

登录

或

标准版

¥16800

元/账号/年

新药情报库 | 省钱又好用!

立即使用

来和芽仔聊天吧

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用