预约演示

更新于:2025-07-26

ZI-MA4-1

更新于:2025-07-26

概要

基本信息

非在研机构- |

权益机构- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批日期- |

最高研发阶段(中国)- |

特殊审评- |

关联

100 项与 ZI-MA4-1 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 ZI-MA4-1 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 ZI-MA4-1 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

1

项与 ZI-MA4-1 相关的新闻(医药)2023-02-15

A slew of biotech companies are pursuing research that could overcome limitations of current cell therapies. Startup creator Replay has a new subsidiary pushing toward the front of the pack with a therapeutic candidate on track to start its first human test this summer—about one year after Replay emerged from stealth. It owes this rapid progress to a cell therapy pioneer’s technology that has already been de-risked by a big pharmaceutical company.

Replay calls itself a genome writing company. With operations split between San Diego and London, the private equity-backed business launched last July with $55 million and a suite of technologies that enable delivery of genetic cargo too big for conventional delivery methods. Those technologies are used by companies Replay forms focused on particular therapeutic areas. To date, it has unveiled companies in retinal eye disease, rare skin disorders, and genetic brain disorders. Syena, launched this week, is Replay’s first cell therapy company.

Currently available cell therapies are made by engineering a patient’s T cells with a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) that targets an antigen on a tumor. CAR T-manufacturing is a lengthy, cumbersome, and expensive process that yields a treatment for a single patient. These treatments also introduce the risk of potentially fatal complications. A growing number of cell therapy developers are trying to improve CAR T with off-the-shelf treatments that overcome manufacturing and safety obstacles. They’re also trying to treat solid tumors, which have eluded first-generation cell therapy. But others are working with a different immune cell, natural killer (NK) cells.

Syena engineers NK cells with a T cell receptor (TCR). Unlike CARs that recognize antigens on the surface of tumors, TCRs can recognize proteins on the inside of a cell, a capability that could empower them to reach cancers that have eluded cell therapies so far. Syena licensed its NK technology from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, where the platform was developed by Katy Rezvani, a professor of stem cell transplantation & cellular therapy and a pioneer in the field. MD Anderson’s approach uses cells obtained from cord blood. Adrian Woolfson, Replay’s executive chairman, president, and co-Founder, said MD Anderson’s technology includes a proprietary method to identify which donors produce the best cells. Woolfson knows of no similar preselection method for T cells. Furthermore, cord blood from a single donor yields up to 100 NK cell therapy doses.

“What you really want to democratize cell therapy is have a scalable process where you can make hundreds of clinical doses in one go, and have them off the shelf,” Woolfson said. “We can do that with these cord blood-derived NK cells.”

Even though Syena’s focus is TCRs, the company owes its start to MD Anderson’s work with CARs. In 2020, the center’s research with CAR NK therapies in lymphoma patients was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Of the 11 patients who received these engineered cells, eight showed a response to treatment. Results also showed no signs of cytokine release syndrome, neurotoxicity, or graft versus host disease—complications common with CAR T-cell therapies.

The published results validated the use of cord blood-derived NK cells to treat cancer. They also paved the way for a deal with Takeda Pharmaceutical, which licensed rights to two MD Anderson CAR NKs and received options for two more. Woolfson followed the developments with interest, and Rezvani was at the top of Replay’s list of potential NK collaborators. But he was unaware at the time that MD Anderson also had TCR NK research. That’s the technology that proved to fit the goal of finding a platform that could be the basis for a Replay cell therapy company.

“We didn’t know if they would want to work with us having done this big deal with Takeda,” Woolfson said. “Over time, they understood the advantages of working with Replay versus the standard big pharma type deal.”

Terms of the MD Anderson deal remain confidential, as is the financing behind Syena. But Replay co-founder and CEO Lachlan MacKinnon said that across all of Replay’s subsidiaries, financing comes from the parent company. Replay also provides a single management team to oversee all of the programs. Under Replay’s model, scientific co-founders retain substantial equity. Beyond money, those scientists gain access to Replay’s stable of genomic technologies, MacKinnon said. Replay believes the future of cell therapy will be highly engineered cells capable of carrying large payloads of molecules, such as chemokines and cytokines. Those capabilities could result in cell therapies better-equipped to tackle difficult-to-treat tumors.

Syena will build an internal pipeline based on the technologies from Replay and MD Anderson, Woolfson said. But over time, Syena could seek to develop those assets in partnership with a large pharmaceutical company. Woolfson added that Syena could also work with TCRs engineered by other companies, but for now the startup has TCRs in hand for its programs.

The NK cell therapy field is growing. Bristol Myers Squibb-partnered Century Therapeutics uses stem cells to develop the NK cells for its therapies. The CAR NK therapies of Nkarta are based on cells sourced from healthy donors. Syena’s closest TCR NK competition might be Zelluna Immunotherapy. The Oslo, Norway-based biotech is developing such cell therapies for solid tumors. Last August, the investment arm of Takeda Pharmaceutical joined Zelluna’s latest financing round with an unspecified sum that the company said will support plans to bring its lead asset into clinical trials and continue preclinical development of other programs. According to Zelluna’s website, the most advanced program, ZI-MA4-1, addresses the cancer protein MAGE-A4. Potential indications include cancers of the lung, ovary, stomach and esophagus, head and neck, and skin.

So far, Syena has disclosed one target: New York esophageal squamous cell carcoinoma 1, or NY-ESO-1. Syena is preparing to bring its NY-ESO-1 cell therapy candidate into Phase 1 testing in both blood cancers and solid tumors.

“We can’t wait to treat the first patients over the summer and present our first data at an international conference in due course,” MacKinnon said.

Image by Flickr user NIAID via a Creative Commons license

细胞疗法免疫疗法临床结果

100 项与 ZI-MA4-1 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

研发状态

10 条进展最快的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 最高研发状态 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 头颈部肿瘤 | 临床前 | 挪威 | 2024-12-01 | |

| 非小细胞肺癌 | 临床前 | 挪威 | 2024-12-01 | |

| 卵巢癌 | 临床前 | 挪威 | 2024-12-01 | |

| 肉瘤 | 临床前 | 挪威 | 2024-12-01 |

登录后查看更多信息

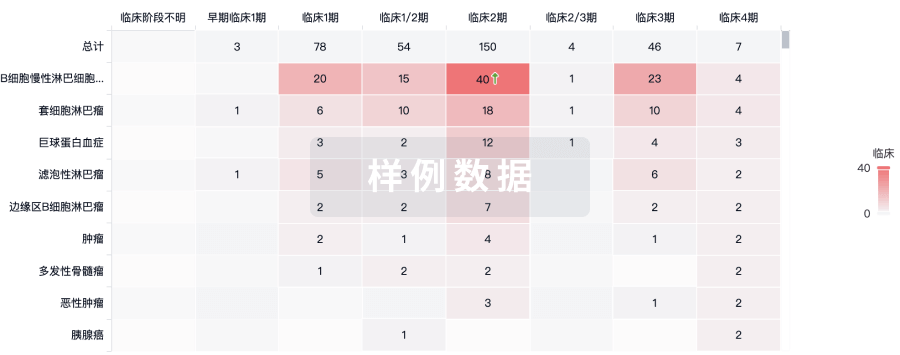

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

| 研究 | 分期 | 人群特征 | 评价人数 | 分组 | 结果 | 评价 | 发布日期 |

|---|

No Data | |||||||

登录后查看更多信息

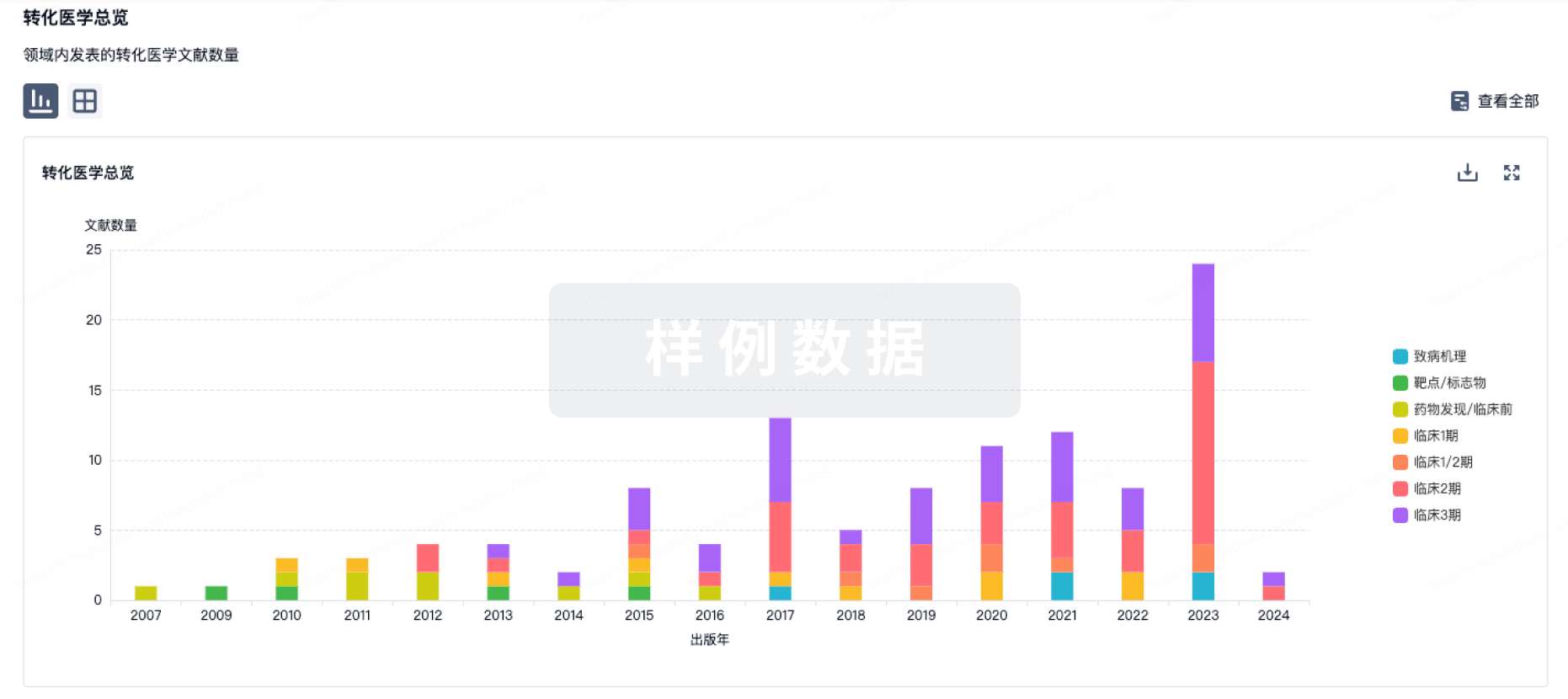

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

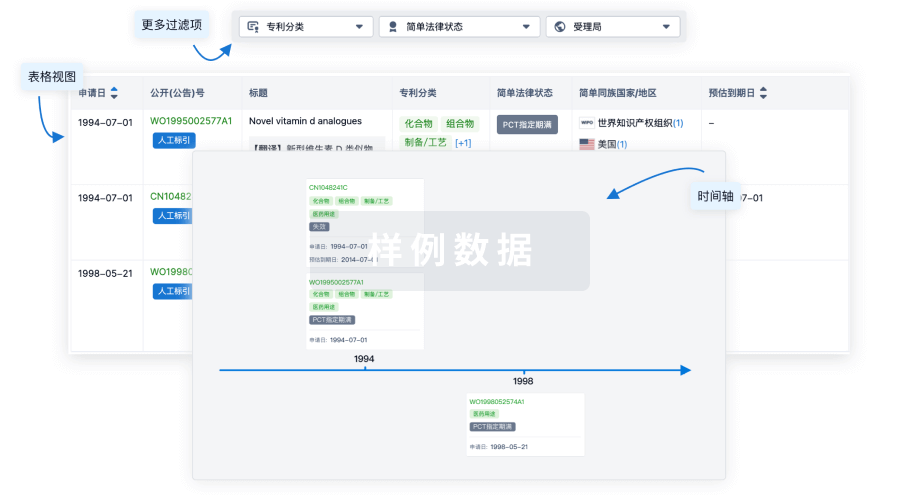

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

Eureka LS:

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用