预约演示

更新于:2025-03-24

SAK-3 (Tohoku University)

更新于:2025-03-24

概要

基本信息

药物类型 小分子化药 |

别名 SAK3、SAK-3 |

作用方式 刺激剂、激活剂 |

作用机制 CAMK2G基因刺激剂(calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II gamma gene stimulants)、Proteasome刺激剂(蛋白酶体刺激剂)、T-type calcium channel激活剂(电压门控性T型钙通道家族激活剂) |

治疗领域 |

在研适应症- |

非在研适应症 |

在研机构- |

非在研机构 |

最高研发阶段无进展临床前 |

首次获批日期- |

最高研发阶段(中国)- |

特殊审评- |

关联

100 项与 SAK-3 (Tohoku University) 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

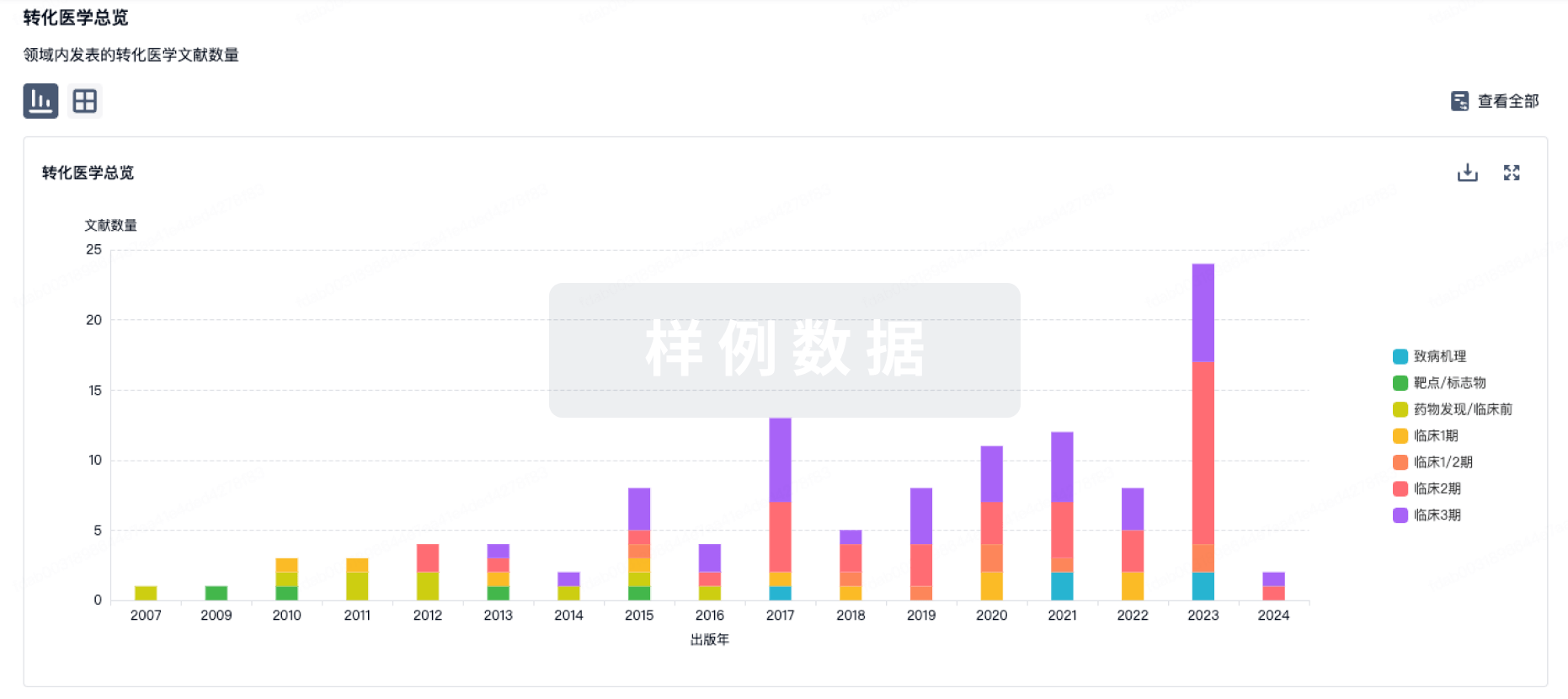

100 项与 SAK-3 (Tohoku University) 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

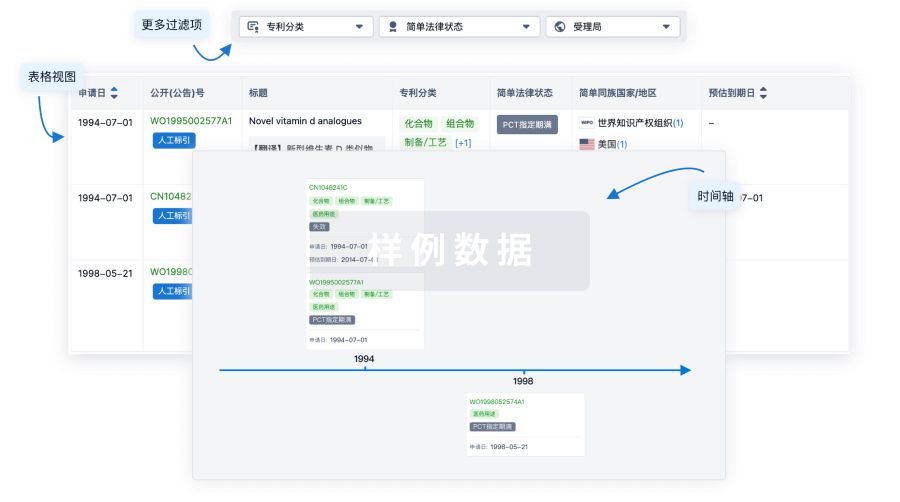

100 项与 SAK-3 (Tohoku University) 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

16

项与 SAK-3 (Tohoku University) 相关的文献(医药)2021-05-01·Journal of pharmacological sciences3区 · 医学

T-type Ca2+ channel enhancer SAK3 administration improves the BPSD-like behaviors in AppNL−G-F/NL−G-F knock-in mice

3区 · 医学

ArticleOA

作者: Izumi, Hisanao ; Fukunaga, Kohji ; Kawahata, Ichiro ; Degawa, Tomohide ; Shinoda, Yasuharu

Alzheimer's disease (AD) accounts for the majority of dementia among the elderly. In addition to cognitive impairment, behavioral and psychological symptoms (BPSD) such as depression tendency and increased aggression impose a great burden on the patient. However, there is still no rational therapeutic drug for BPSD. Recently, we developed a novel AD therapeutic candidate, SAK3, and demonstrated that it improved cognitive dysfunction in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F knock-in (NL-G-F) mice. In this study, we investigated whether acute SAK3 administration improved BPSD in addition to cognitive improvement. Acute SAK3 administration improved BPSD, including anxiolytic and depressive-like behaviors, and ameliorated aggressive behaviors. Furthermore, continuous SAK3 administration improved anxiolytic and depressive-like behaviors. Intriguingly, the anti-anxiolytic and cognitive improvement lasted two weeks after the withdrawal of SAK3, whereas the anti-depressive action did not. Taken together, SAK3 had comprehensive beneficial effects on BPSD behavior.

2021-02-01·Neurobiology of disease2区 · 医学

Evaluation of the effects of the T-type calcium channel enhancer SAK3 in a rat model of TAF1 deficiency

2区 · 医学

Article

作者: Fukunaga, Kohji ; Janakiraman, Udaiyappan ; Nelson, Mark A ; Dhanalakshmi, Chinnasamy ; Khanna, Rajesh ; Moutal, Aubin

The TATA-box binding protein associated factor 1 (TAF1) is part of the TFIID complex that plays a key role during the initiation of transcription. Variants of TAF1 are associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Previously, we found that CRISPR/Cas9 based editing of the TAF1 gene disrupts the morphology of the cerebral cortex and blunts the expression as well as the function of the CaV3.1 (T-type) voltage gated calcium channel. Here, we tested the efficacy of SAK3 (ethyl 8'-methyl-2', 4-dioxo-2-(piperidin-1-yl)-2'H-spiro [cyclopentane-1, 3'-imidazo [1, 2-a] pyridine]-2-ene-3-carboxylate), a T-type calcium channel enhancer, in an animal model of TAF1 intellectual disability (ID) syndrome. At post-natal day 3, rat pups were subjected to intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of either gRNA-control or gRNA-TAF1 CRISPR/Cas9 viruses. At post-natal day 21, the rat pups were given SAK3 (0.25 mg/kg, p.o.) or vehicle for 14 days (i.e. till post-natal day 35) and then subjected to behavioral, morphological, and molecular studies. Oral administration of SAK3 (0.25 mg/kg, p.o.) significantly rescued locomotion abnormalities associated with TAF1 gene editing. SAK3 treatment prevented the loss of cortical neurons and GFAP-positive astrocytes observed after TAF1 gene editing. In addition, SAK3 protected cells from apoptosis. SAK3 also restored the Brain-derived neurotrophic factor/protein kinase B/Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Beta (BDNF/AKT/GSK3β) signaling axis in TAF1 edited animals. Finally, SAK3 normalized the levels of three GSK3β substrates - CaV3.1, FOXP2, and CRMP2. We conclude that the T-type calcium channel enhancer SAK3 is beneficial against the deleterious effects of TAF1 gene-editing, in part, by stimulating the BDNF/AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway.

2020-09-01·Neurobiology of disease2区 · 医学

The investigation of the T-type calcium channel enhancer SAK3 in an animal model of TAF1 intellectual disability syndrome

2区 · 医学

Article

作者: Boinon, Lisa ; Yu, Jie ; Dhanalakshmi, Chinnasamy ; Nelson, Mark A ; Janakiraman, Udaiyappan ; Fukunaga, Kohji ; Khanna, Rajesh ; Moutal, Aubin

T-type calcium channels, in the central nervous system, are involved in the pathogenesis of many neurodegenerative diseases, including TAF1 intellectual disability syndrome (TAF1 ID syndrome). Here, we evaluated the efficacy of a novel T-type Ca2+ channel enhancer, SAK3 (ethyl 8'-methyl-2', 4-dioxo-2-(piperidin-1-yl)-2'H-spiro [cyclopentane-1, 3'-imidazo [1, 2-a] pyridine]-2-ene-3-carboxylate) in an animal model of TAF1 ID syndrome. At post-natal day 3, rat pups were subjected to intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of either gRNA-control or gRNA-TAF1 CRISPR/Cas9 viruses. At post-natal day 21 animals were given SAK3 (0.25 mg/kg, p.o.) or vehicle up to post-natal day 35 (i.e. 14 days). Rats were subjected to behavioral, morphological, electrophysiological, and molecular studies. Oral administration of SAK3 (0.25 mg/kg, p.o.) significantly rescued the behavior abnormalities in beam walking test and open field test caused by TAF1 gene editing. We observed an increase in calbindin-positive Purkinje cells and GFAP-positive astrocytes as well as a decrease in IBA1-positive microglia cells in SAK3-treated animals. In addition, SAK3 protected the Purkinje and granule cells from apoptosis induced by TAF-1 gene editing. SAK3 also restored the excitatory post synaptic current (sEPSCs) in TAF1 edited Purkinje cells. Finally, SAK3 normalized the BDNF/AKT signaling axis in TAF1 edited animals. Altogether, these observations suggest that SAK3 could be a novel therapeutic agent for TAF1 ID syndrome.

1

项与 SAK-3 (Tohoku University) 相关的新闻(医药)2021-07-02

Every week there are numerous scientific studies published. This week there was an unusual number of research stories revolving around Alzheimer’s disease. Here’s a look at some of the more interesting ones.

Simple Blood Test for Early Detection of Alzheimer’s

Investigators at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology developed a simple blood test for early detection and screening of Alzheimer’s disease. It has an accuracy of more than 96%. The team identified 19 out of the 429 plasma proteins associated with Alzheimer’s to form a biomarker panel that provides an AD signature in the blood. They then developed a scoring system that could differentiate AD patients from healthy people, and also differentiate among the early, intermediate, and late stages of the disease. They published their research in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

“With the advancement of ultrasensitive blood-based protein detection technology, we have developed a simple, non-invasive, and accurate diagnostic solution for AD, which will greatly facilitate population-scale screening and staging of the disease,” said Nancy Ip, Morningside Professor of Life Science and the director of the State Key Laboratory of Molecular Neuroscience at HKUST.

The research was conducted with the University College London and local hospitals including the Prince of Wales Hospital and Queen Elizabeth Hospital. It utilized the proximity extension assay (PEA) to study the levels of more than 1,000 proteins in the plasma of AD patients in Hong Kong.

Reversing Dementia in Mice

Investigators at Tohoku University identified a potential therapeutic that not only seems to halt neurodegenerative symptoms in laboratory animals, but seems to reverse the effects of the diseases, specifically dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. They published their research in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences, and the Japanese regulatory board has declared the drug safe, and the researchers expect to begin human clinical trials next year. In earlier research, the research team found that the SAK3 molecule seemed to improve memory and learning in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. SAK3 seems to enhance the function of a cell membrane channel, further promoting neuronal activity in the brain. The same drug, SAK3, also seemed to work in a mouse model of Lewy body dementia. And even after onset of cognition problems, the drug seemed to significantly prevent the progression of neurodegenerative behaviors in motor dysfunction and cognition. One of the key theories of Alzheimer’s is that it is caused or exacerbated by the accumulation of amyloid plaques. The recently approved Biogen drug Aduhelm is a monoclonal antibody that clears beta-amyloid. The researchers note that SAK3 inhibits the accumulation of misfolded alpha-synuclein, which is associated with neurodegenerative disorders, but also, at least in mice, also destroys amyloid plaque.

New Alzheimer’s Database in Diverse Populations Now Available

The University of North Texas Health Science Center has made available a database with data that came out of the Health and Aging Brain among Latino Elders (HABLE) study that was launched in 2017. The data includes the biology of Alzheimer’s among Mexican Americans as well as non-Hispanic whites within the context of sociocultural, environmental and behavioral factors. One of the early findings is that beta-amyloid, one of the biomarkers of Alzheimer’s, is less common among Mexican Americans yet this population appears to have a younger onset of cognitive loss. Approximately 1,000 Mexican Americans and 1,000 non-Latino whites over 50 from North Texas have enrolled in the study. The data accumulated include reoccurring and free comprehensive interviews, functional exams, clinical lab tests, a brain MRI and PET scans.

Key Tau Switch that Triggers Protein Accumulation in Alzheimer’s IDed

Researchers at the Tokyo Metropolitan University have identified a specific feature of the tau protein that causes it to accumulate in the brain and trigger Alzheimer’s and other tau-related illnesses. Disulfide bonds on specific amino acids stabilize tau and cause it to accumulate, which gets worse with increased oxidative stress. Normally, tau helps form and stabilize microtubules, the filaments that crisscross the inside of cells and help keep them structurally rigid. But when they don’t form correctly, they accumulate in sticky clumps. These clumps in the brain block the firing of neurons, involved in a wide range of neurodegenerative diseases called tauopathies, of which Alzheimer’s is one. They published their research in Human Molecular Genetics.

Saturated Fatty Acid Levels Rise as Memories are Made

Researchers at the University of Queensland found that saturated fatty acid levels rise in the brain during the formation of memories. They were testing the most common fatty acids, which were viewed as important to health and memory, but were surprised to find that the changes of saturated fat levels in the brain cells were most pronounced when new memories were formed. In particular, the most marked was myristic acid, found in coconut oil and butter. Fatty acids are the building blocks of lipids or fats and are important for communication between nerve cells. The highest concentration of saturated fatty acids was in the amygdala, the part of the brain that forms new memories specifically related to fear and strong emotions.

Maybe it’s Not Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s, but Amyloid-Beta Peptide

Even with Biogen’s approval of aducanumab to remove amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s patients’ brains, the amyloid theory is being debated. A study out of the University of Cincinnati theorizes that amyloid plaques—hardened clumps of beta-amyloid—may be a consequence of Alzheimer’s, but not the cause of the memory and cognition issues. In their research, they found that cognitive impairment appeared to be due to a drop in soluble amyloid-beta peptide instead of the accumulation of amyloid plaques. They analyzed the brain scans and spinal fluid from 600 people enrolled in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study, who all had amyloid plaques. They compared the amount of plaques and levels of the peptide in the people with normal cognition to those with cognitive impairment. They found that the individuals with high levels of the peptide were cognitively normal, regardless of the amount of brain plaques. They also found higher levels of the peptide were associated with a larger hippocampus, the area of the brain associated with memory.

“It’s not the plaques that are causing impaired cognition,” says Alberto Espay, the study’s senior author and professor of neurology at UC. “Amyloid plaques are a consequence, not a cause.” He went on to say that future approaches will look at replenishing these brain soluble proteins to normal levels.

抗体

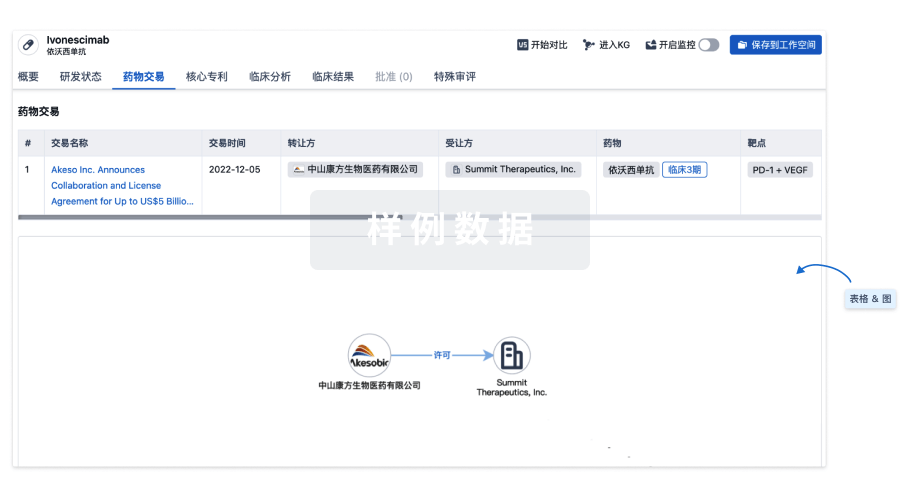

100 项与 SAK-3 (Tohoku University) 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

研发状态

10 条进展最快的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 最高研发状态 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 阿尔茨海默症 | 临床前 | 日本 | 2015-07-01 |

登录后查看更多信息

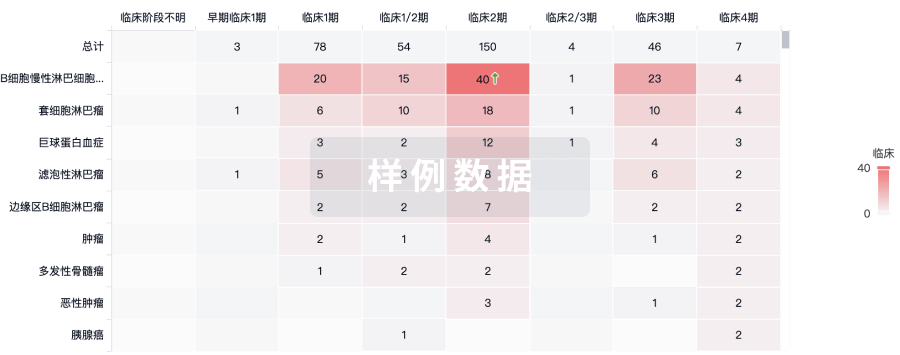

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

| 研究 | 分期 | 人群特征 | 评价人数 | 分组 | 结果 | 评价 | 发布日期 |

|---|

No Data | |||||||

登录后查看更多信息

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

来和芽仔聊天吧

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用